NEW TECHNOLOGIES

The Converging Digital Universe

Selby Bateman, Features Editor

The Converging Digital Universe

Selby Bateman, Features Editor

The digitization of America is well under way. Thanks to a wave of new consumer electronics products, this year more people than ever will see and hear how the convergence of digital audio, video, satellite, telephone, optical, laser, television, and computer technologies is transforming the world. Yet, the phenomenon is just beginning.

The winds of technological change have been blowing a gale for the past few years. And the forecast shows no indication of a letup. In fact, millions of consumers will begin to reap a resulting whirlwind of new high-tech products for the home, office, and classroom. Consider the following:

• A home stereo system answers your phone, takes messages, and alerts you to incoming calls.

• With the push of a button, your video film recorder captures a picture from your favorite TV show and instantly prints out a still photo for your wallet.

• Your 20-volume set of encyclopedias, contained and crossindexed on a compact disc in a player connected to your computer, searches and prints out 37 reference sources on your selected topic in less than 30 seconds.

• The satellite dish in your backyard automatically tracks various communication satellites based on the pattern of TV programs you want to watch each night. At the same time, your computer is receiving and storing financial data that unobtrusively shares the same incoming satellite transmission to your TV.

• The digital TV in your living room displays two small windows on the screen while you watch a program uninterrupted; one window shows the changing stock quotations, while the second window displays a program from a different channel or previews a tape from your videocassette recorder.

• The computer image recorder connected to your personal computer makes a 35 mm slide, color print, or overhead transparency of the business chart or digital painting you've just created.

Does any of this sound farfetched? You'll be able to buy products this year that do all of these things and more. If it seems difficult to keep up with the latest news about consumer electronics, it's not your fault. Never have so many dramatic technological changes produced so many new capabilities and products in so short a time. What has become strikingly clear is that all of these innovations share a common foundation-the digital, microprocessor-based world of computer electronics.

These changes have become so important to our lives and our pocketbooks that market researchers are now targeting a new group of consumers: Technologically Advanced Families (TAFs). Could "yuppies" eventually be surpassed in importance by "taffies," households that purchase and use the latest computers, VCRs, stereo TVs, 8 mm camcorders (camera recorders), compact disc players, satellite dishes, and dozens of other products? Consumer electronics manufacturers and retailers believe that these households are the important leading-edge market for their array of new products.

Among the catalysts sparking enthusiasm for the latest in hightech gear, none is more important than the personal computer phenomenon of the past half-dozen years. Not only are computer owners the bedrock of the TAFs, but the new generation of 16/32-bit computers is powerful enough to work with just about any other consumer electronics product. Suddenly, devices like VCRs, compact disc players, electronic keyboards, and camcorders have become computer peripherals. As these products continue to become more sophisticated and flexible, their technologies converge and their capabilities expand. In the world of consumer electronics, the whole has indeed become more than the sum of its parts.

The development of the microcomputer has accelerated an already rapid evolution, says David Allen, president of Boston Media Consultants and a writer specializing in TV production, computers, videodiscs, and videotape. "They come along with greater speed. That's not a function of any interactivity, that's just a curve that the computer industry and microelectronics industry are on.

"Each development feeds the next development in a serendipitous way that makes succeeding developments faster to accomplish," says Allen. "You can really say that we're now to the point at which you could almost create any technological package you could conceive of, if you don't put a price restriction on it. Nothing is technologically impossible, in a broad sense. But it has to be accompanied by some kind of way to get return on investment. And that's what slows things down more than anything else right now. It's marketdriven, not technologically driven."

During the past year, a parade of new technologies has entered the computer scene. The arrival of MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) has opened the doors to a new world of computer-based music composition and performance (see "Making Music with MIDI," COMPUTE!, January 1986). Laserdriven compact disc technology has branched out from stereo systems to computer data storage and retrieval. Smaller, less expensive video cameras and camcorders that connect with VCRs and computers are making inroads in consumer markets.

In addition, a new family of audio/video hardware and software products has been created to take advantage of the latest computers, particularly the Commodore Amiga, Atari ST, and Apple Macintosh.

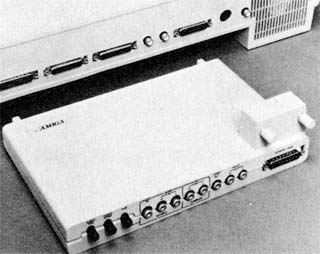

It's appropriate that in this age of video one of the most promising fields of development is computer control of video images that originate from video cameras, VCRs, laser disc players, other computers, or TVs with video outputs - essentially any device that puts out a composite video signal. For instance, Commodore is releasing two fascinating video peripherals for the Amiga: the Genlock, which plugs into the back of the Amiga and mixes external video signals with the computer's own video output; and the Amiga LIVE digitizer (formerly known as the "frame grabber"), which captures and digitizes an external video image in the Amiga itself.

Commodore/Amiga's

Genlock accessory tucks

beneath the rear of the Amiga computer and

permits sophisticated video image mixing.

beneath the rear of the Amiga computer and

permits sophisticated video image mixing.

"Genlock is external to the Amiga and externally mixes two video sources, one of them the Amiga's," explains Paul Higginbottom, an Amiga product manager at Commodore. "So you take the Amiga's video source and the external video source, and you combine them-and the audio as well. Nothing comes into the Amiga with Genlock. With Amiga LIVE, a digitized picture is brought into the Amiga. So one [Genlock] is doing superimposing, and the other [Amiga LIVE] is actually taking an image and bringing it in.

"They operate separately, but you could certainly use them together," says Higginbottom. "You may want to take a real image and put Amiga's graphics on it, and digitize those back into the Amiga again."

Immediate applications for the Genlock include on-screen titling for video presentations or home movies, "electronic chalkboard" effects similar to those used for TV sports analysis, and special video effects achieved by mixing Amiga graphics with other video images. At the Amiga's official unveiling in New York last summer, artist Andy Warhol used a video camera, Genlock, and Amiga LIVE to digitize a picture of rock singer Deborah Harry, then used a mouse-controlled graphics program to "paint" the video image with new colors. Amiga LIVE can be used not only for special video effects such as these, but also for video databases, says Higginbottom.

"We don't just mean pretty pictures. If you're a real estate agent or an architect, or you have a parts list you want to inventory, something like that-then you can have a video inventory," he explains. "And Amiga LIVE performs in realtime, not like most digitizers you see that usually take anywhere from 8 to 30 seconds to generate the picture on the screen. This is in realtime; if you have a movie camera, you'll see the image move as you move the camera."

Both the Genlock and Amiga LIVE are expected to be available in April or May, pending final FCC approval. Each accessory will cost about $249.95.

A different video digitizer is in the works for the Atari ST and should be available by the time you read this. Hippopotamus Software is introducing the Hippovision Video Digitizer this spring for the ST and plans to have a version available later for the Amiga. (No price announced yet.)

"Anything that produces video signals, you just plug into the [digitizer] box that's connected to the computer," says Clint Ballard, vice president of engineering for the Los Gatos, California firm. "You press a button when you get a picture you like, and there you have it. We'll also have image processing software with which you can change around the colors-do whatever you want with it. This really opens up the graphics world."

For the Macintosh, which has a two-year head start on the Amiga and ST, there are already several video digitizers and compatible graphics programs available. MacVision from Koala Technologies, Micro-Imager from Servidyne Systems, Inc., Thunderscan from Thunderware, Inc., and a few others make excellent use of the Mac's high-resolution monochrome graphics. Since the Amiga and the ST each boast superb color graphics as well as high-resolution modes surpassing the Mac's, video digitization hardware and graphics software are becoming even more flexible and powerful.

As computers grow more capable of handling video images, other manufacturers are gearing up to take advantage of new markets expected to develop. Toshiba and Polaroid have announced products which strengthen the connections among computers, photography, and video. The two companies are jointly introducing a new instant video film recorder that produces instant color prints or slides from a TV set or monitor and has optional RGB (red-green-blue) computer input. The recorder features digital freeze-field capture, color preview capability, and accepts standard NTSC (National Television Standards Committee) signals.

The recorder captures and digitizes any image from a TV screen, whether the signal originated from a broadcast station, VCR, video camera, or any other standard video device. When equipped with the appropriate camera, the result is an instant photo print or 35 mm slide. With the push of a button, you could freeze one frame of your home movies, your favorite rock video, or a TV show, and then instantly produce a color picture. The recorder is expected to be available by midyear.

Polaroid is also introducing this year an improved version of its Palette computer image recorder. The Palette provides presentationquality photos from computer graphics generated by a wide variety of computers, such as the Apple II series and the IBM PC family. It's capable of handling image resolutions up to 920 X 700, depending on the combination of hardware and software. Almost all presentation-graphics and graphics-editing software is compatible with the under-$2,000 system.

Although few personal computer owners will spend several thousand dollars to buy such video systems for the home, the next few years will see dramatic price drops as technology improves and costs decline.

For example, Kodak's Consumer Electronics Division plans to introduce a still video system that allows you to select and record individual video images. The system's player/recorder captures images in realtime from any NTSC video signal and stores up to 50 images on a tiny floppy disk. An adjunct to this system is a film-to-disk transfer station that may be installed at film processors; you could have 35 mm color negatives transferred to the floppy disk, then view the pictures at home on your TV-ordering regular prints later, if you like.

Kodak had also planned to announce a new color video imager for producing instant prints of any video image. However, a recent decision by the U.S. Supreme Court on behalf of Polaroid has forced Kodak to withdraw from the instant photography business. Although Kodak had expected initial sales of the video imager to be in commercial and industrial applications, the long-range plan was to make the product part of home computer and video centers, according to Richard D. Lorbach, vice president of Kodak's consumer division.

"We anticipate that the color video imager eventually will be used as a home entertainment center component," said Lorbach before the court decision was handed down. "Our market research indicates that there is significant consumer interest in being able to make photographs of personal images displayed on TV screens."

This type of video system presents a wide range of possibilities. For example, by capturing images from your home videos, you could make a slide show of still shots or produce prints or slides for family albums. Computer artists could take their digital paintings or images captured from a video source and create their own sequenced video show. With the appropriate computer software, text could be overlayed on any of the images.

There are hundreds of business and industrial applications for this technology. Rather than spending thousands of dollars on outside production of sales and marketing presentations, almost any business would have access to high-quality video production. A real estate agency could take photos or videotapes of its properties, add textual information on prices and other details, and then show the resulting package to their customers. Any of the frames could be turned into glossy prints for the house-hunters to keep for reference. The ramifications are virtually limitless.

One of the most important developments in the marriage of computer and video technology is the introduction of digital TVs-TV sets that convert the incoming analog broadcast signal into digital form. Toshiba, Sony, and most of the other large consumer electronics companies have invested millions of dollars to develop digital TV. Exceptionally clear pictures are only one of the benefits of this research. Digital TVs also have what's called PIP (picture-in-picture) capabilitythey can partition the viewing screen by opening separate "windows" for simultaneously displaying other video signals.

An example is the 26-inch DT2680A TV receiver/monitor from NEC Home Electronics. It can simultaneously display the picture from the station that's tuned in plus moving pictures from any of three auxiliary video inputs, or color computer graphics through the set's RGB input. You can watch two channels at once, or a channel and a videotape, or even work with your home computer while watching TV on the same screen.

The picture you'll be watching is much sharper, too. Today's conventional TVs offer approximately 250 lines of horizontal screen resolution, while the NEC digital TV is capable of resolving up to 500 lines. This is actually more resolution than is available from broadcast signals. Through special filtering, the digital TV displays a broadcast screen resolution of 336 lines-the best that's possible with today's broadcasts.

In addition, the NEC digital TV has enough microprocessor-based memory to store up to three differ ent still video pictures at a time. By pressing a button on the remote control, you can capture any video image and display it as an 8½-inch (diagonal) window within the 26-inch screen. Meanwhile, the background video image is unaffected. You could freeze-frame a fullback plowing through the line while watching the play continue on the main screen.

As might be expected, the connection capabilities and special features of such a TV set go far beyond the few video and audio plugs found on even the better current sets. The NEC digital TV contains a stereo amplifier and stereo speakers, three sets of line video inputs for VCRs, video disc players, color cameras, and home computers, and an eight-pin RGB input. Outputs include a monitor jack that carries whatever is on the screen, a TV output that carries whatever channel is tuned, external speaker outputs, fixed audio line outputs for recording, and variable audio line outputs for volume-controlled connections to an external sound system.

As NEC vice president Gerry Tangney says, this "is a taste of the future of home TV." The NEC digital set is expected to be introduced in May, with the price to be announced soon.

Another new technology already on the horizon is high-definition TV (HDTV), an enhanced broadcast signal that offers 1,125 scan lines of information instead of the 525 now used in conventional American TV broadcasting. This would require broadcasters to upgrade their equipment, however, and efforts to adopt an HDTV Standard have reportedly been mired in international and corporate disagreements over how to bring about this doubling of screen clarity.

The growing popularity of compact disc (CD) audio players has given new impetus to the development and widespread consumer distribution of their digital data cousins, called CD-ROMs (Compact Disc-Read Only Memories). Although these laser discs are only 4.72 inches in diameter, they are capable of storing 600 megabytes of information on a single side, with an access time of seconds.

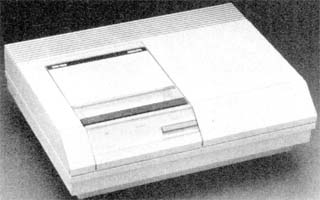

The first company out the door with CD-ROM players in the retail market is the Subsystems and Peripherals Division of North American Philips Corporation. Its CM 100 disc player and CM 155 controller card works with the IBM PCcompatible computers (other interfaces will be announced this year). Available with the Philips CD-ROM player is Grolier's The Electronic Encyclopedia, the equivalent of a 20-volume reference collection on just about a quarter of one side of a CD-ROM disc. Although the initial purchase price of $1,495 may keep initial sales out of the home market in volume, the price for CD-ROM technology is expected to drop quickly over the next couple of years.

Philips has introduced its CD-ROM drive which

comes with Grolier's Electronic Encyclopedia on

a compact disc. The entire package sells for $1,495.

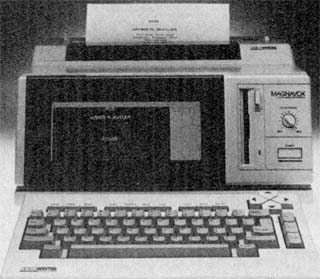

Technology occasionally moves in mysterious ways, and an example can be seen in new prod ucts which have taken advantage of the popularity-and intimidation -of word processors. Casio's new CW-30 Personal Typewriter blends the comforting familiarity of a typewriter with the ease of use of a computer word processor. The $399.95 hybrid machine looks very much like a standard electric typewriter. But a quick look at the keyboard also shows a set of cursor and special function keys, plus a 15-character liquid-crystal display window for editing.

This Casio computer-compatible electronic

typewriter is a hybrid-part typewriter and

part word processor-that can connect to

a computer to serve as a printer.

One of the most interesting features of the Casio typewriter is that it's computer-compatible. It contains both a Centronics-standard parallel interface and an RS-232 serial interface that lets the typewriter become a computer printer (plain or thermal paper). It can be hooked up to a 300 baud modem for uploading and downloading text with a computer. It has built-in pica and elite pitches, right justification, and multiple type fonts: boldface, underlining, double-wide characters, special symbols, and foreign alphabet characters. It has enough memory to store two pages of text, and with an optional memory expander, up to ten pages of text. Small removable memory cards let you save and store text. Casio obviously hopes to capture the best of both worlds, typewriters and word processors, at the same time it is attracting those who don't want to give up typewriters, but are fearful they're being left behind by word processors.

The Magnavox VideoWriter is an $800 dedicated

word processor aimed at the home market.

Magnavox has taken a different approach with its new Videowriter, a dedicated home word processor that contains its own software, printer, spelling checker, and 18-line monitor (smaller than a regular computer screen, but larger than most portable computers). The $800 Videowriter has a memory capacity of approximately 70 pages of text, automatically stored on standard 3½-inch disks. While dedicated word processors have been used in offices for years, it's unusual to see such a product for the home market, especially considering the number of people who buy multipurpose computers primarily for word processing.

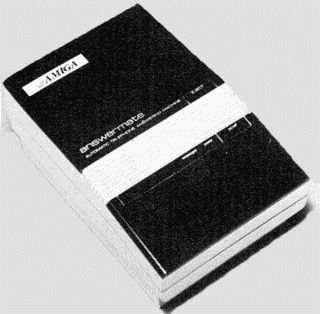

Computers are converging with yet another technology, too - telephones. For example, Commodore is planning to introduce its new 1100 AnswerMate, a programmable computer-controlled telephone answering machine for the Amiga. The AnswerMate connects to the Amiga's RS-232 port and to a telephone. Not only does it play back your taped greetings and record messages, but it also can respond with messages generated by the Amiga's built-in synthesized voice. And multitasking software included with the AnswerMate lets it answer phone calls while you're busy using the computer for other things. (Price to be announced.)

Commodore's AnswerMate connects to the Amiga

computer to serve as a telephone answering

machine that can make use of the Amiga's

multiprocessing and synthesized speech capability.

There is scarcely an area of consumer electronics which is not moving either directly or indirectly toward the personal computer, either as a peripheral or as a microprocessor-based stand-alone device. Even the ways in which computer users receive their software may be undergoing change in the future.

For example, Cauzin Systems, with backing from Kodak, has developed the Softstrip system of information storage. Data is encoded on a strip of paper in a format similar to-but more compact than-the familiar bar codes found on consumer products. One strip, which typically measures 9½ by 5/8 inches, can store up to 5,500 characters (about three typewritten pages). The strips can be printed on ordinary paper and are read by an electro-optical scanner. Connected to a computer, the scanner reads the coded strips and transfers the data into memory for later storage on disk.

Further examples of converging electronics technologies abound in virtually every field. The emergence of stereo TVs and VCRs, coupled with a stereo-capable computer such as the Amiga, obviously opens new possibilities for audiophiles. Interactive video, spurred by improvements in laser discs, is another rapidly evolving technology with a connection to personal computing. Radio signals relayed by satellites can carry data accessible by computer users. Use of electronic mail systems is expected to jump from less than a billion messages a year today to more than 20 billion by the end of the decade, ultimately becoming a major service as common as the telephone and the U.S. mails.

As media consultant David Allen noted earlier, technology is capable of virtually anything today; but the successful marketing of an idea is the key to its success. In the forseeable future, neither technology nor the marketplace shows any signs of slowing down.