Kathy Yakal, Feature

Writer

Though some authors and stars are lending only their names to entertainment software, others are actively contributing to the game's design. Here's a look at what's happening.

You see it practically every time you flip through a magazine or turn on the television. Fame lending its name to the cause of advertising. Tennis players and movie stars and race-car drivers hawking shampoo and sports equipment and clothing lines.

We've seen the same thing happen with microcomputers, famous faces and voices telling us which one to buy. Some entertainment software publishers are taking it a step farther; instead of promoting a package, the personality is a major part of the software, either as one of the game's characters, or even its designer.

he Trillium series, produced by a division of Spinnaker Software, is one of the best examples of this trend. It's a series of interactive adventure games for the Commodore 64 and Apple II-series computers, based on novels by well-known science fiction authors.

In each of the games, the player takes the role of the novel's main character, encountering his or her problems and making decisions. Full-color graphics and a sophisticated parser that understands several hundred words make the games easy to play. A hint book and word list are included in each package.

In late 1983, Spinnaker approached writer Michael Crichton, thinking that some of his works might lend themselves well to adventure games. He surprised them. He was just completing work on an adventure game of his own. "They came to acquire book rights and ended up taking a finished game," says Crichton.

Crichton, author of The Andromeda Strain and Congo, and writer/director of many science fiction films, was very interested in interactive fiction. He had been asked to do some creative work using laser disks but declined, believing that they couldn't be accessed in a sufficiently sophisticated fashion.

Books, breakers, bad guys, and Bruce: Personalities and trends find a place in computer games. Pictured from left to right are Fahrenheit 451, part of the Trillium series from Spinnaker; Creative Software's Break Street; Spy vs. Spy, First Star Software's adaptation of the comic strip from MAD magazine; Bruce Lee, from Datasoft; and the joint project of Infocom and author Douglas Adams, A Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy.

Spinnaker's Trillium series, pictured from left to right, top row: Rendezvous With Rama, Amazon, Shadowkeep, and Dragonworld.

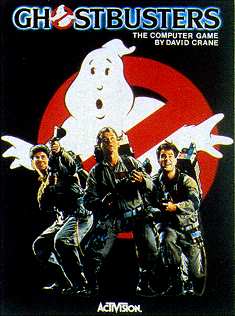

In this scene from Ghostbusters, a ghost is being sucked up by a ghost vacuum as the player drives from one building to another.

He had hired programmer Steve Warrady in 1982 to help translate an original story into Apple assembly language. The result was Amazon, a graphics and text adventure in which the player is an agent for NSRT, a high-tech research firm. The player must travel to the Amazon and recover valuable emeralds hidden in the Lost City of Chak, with the help of a friendly (and often sarcastic) bird named Paco.

Fahrenheit 451, another game in the Trillium series, is a sequel to Ray Bradbury's book of the same name. As Guy Montag, the player lives in a future totalitarian society whose government is committed to controlling the populace by destroying all literature. Montag's mission is to restore to the world the freedom it once had.

Rendezvous With Rama is based on the Arthur C. Clarke novel. The player, as captain of a small scout spaceship which has just encountered an alien starship hurtling into the solar system, must explore it and try to make contact with alien intelligence. (Clarke wrote a new ending to be used in the game.)

The fantasy Dragonworld, by Byron Preiss and Michael Reaves, sends the player on a journey to rescue The Last Dragon from the Duke of Darkness.

And here's an interesting twist: Science fiction writer Alan Dean Foster wrote a novel based on the fantasy game Shadowkeep. The player's task is to recapture the Shadowkeep, with its mazes and monsters, and to free the good wizard Nacomedon. Up to nine characters may be chosen by the player while exploring the keep. Designed as an interactive adventure, the game incorporates many aspects of role-playing fantasy software.

Who ya gonna call?

oftware designer David Crane, a cofounder of Activision,

went to see the movie Ghostbusters on

the recommendation of a friend. "I think I may have enjoyed it a lot

more than some people because it was sprung on me," he says. "From the

first special effect, you knew that there was something here that

wasn't just stand-up comedy."

oftware designer David Crane, a cofounder of Activision,

went to see the movie Ghostbusters on

the recommendation of a friend. "I think I may have enjoyed it a lot

more than some people because it was sprung on me," he says. "From the

first special effect, you knew that there was something here that

wasn't just stand-up comedy."Two days after he saw the movie, someone at Activision asked if he'd like to write a computer game based on the movie. He took a day to think about it. "To do justice to any game takes no less than 500 hours of my time, and I was going to get married in six weeks."

His decision to do it was based partly on the fact that he had already been working on the game without knowing it. For a couple of months, Crane had been trying to develop a game that had something to do with equipping a car and driving it around city streets, but it was going nowhere. "It was a game concept in search of a theme," he says.

And the Ghostbusters theme fit perfectly. The theme song from the movie plays throughout the game (you can sing along by following the bouncing ball at the game's opening) as you buy a car and outfit it with equipment like ghost bait (to trap the marshmallow man) and a ghost vacuum (to suck up ghosts as you drive through the streets of the city). Buildings flashing red are ghost-ridden, and it's your job to maneuver each ghost into a ghost trap before he "slimes" you. The game is won when you've captured enough ghosts to enter Zuul.

"It's an amazing coincidence that what I was doing followed the script of the movie. I was able to put the theme and game together in such a way that I could have what's really an original game concept that embodied the spirit of the movie.

here were no coincidences involved in the development of Infocom's computer game version of A Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, just a lot of mutual admiration. "Most people at Infocom were Hitchhiker's fans, and Douglas Adams [author of the book] was an Infocom game player," says Steve Meretzky.

A Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy is the story of Arthur Dent, an ordinary human being who is thrust into some rather extraordinary circumstances. After being told by Ford Prefect (an alien in disguise) that the earth is about to be destroyed, he hitches a ride on a Volgon spaceship, where he is tortured by having poetry read to him. Surviving that, he is ejected into space, and is rescued by the Heart of Gold, another spaceship, and brought to the planet Magrathea. Improbable things continue to happen as the zany plot unfolds.

Meretzky, a program designer for Infocom, and Adams worked together to translate the book's themes, characters, and humor into a text adventure. "The game starts out following the book pretty closely, up to your arrival on the Volgon ship," he says. "From that point, until you get to the Heart of Gold, the general story line is pretty similar, but a lot of the more specific things that happen aren't the same things that happen in the book.

"By the time you get to the Heart of Gold, the story diverges almost completely from the story line of the book. But there are a number of things that are just sort of alluded to in the book that are gone into in much more detail in the game."

Adams, whose home is in England, visited Meretzky at Infocom for about a week to map out the initial design of the game. They found that their creative styles differed. Meretzky, who had previously designed Planetfall and Sorcerer for Infocom, usually came up with an overall concept for a game, then went back and filled in details. Adams did it the opposite way-details first.

So they kept in constant contact via electronic mail as Meretzky was programming, then met again in England for some intense final sessions ("We basically holed ourselves up in a country inn and didn't come out until we had finished").

Meretzky found a different kind of challenge in programming a game whose story line had basically been written by someone else. "In some ways it's easier, and in some ways it's harder," he says. "It's easier because you have some constraints on the universe you're going to be designing, and on the characters you're going to be using, and a lot of the situations, and you don't have to come up with as many ideas.

"But on the other hand, there's more of a challenge because you want to take advantage of the features of an interactive game, and you don't want it to be just a translation of the book, because the book is necessarily linear. You want to take advantage of the features and the power of the computer to do something different."

Datasoft's The Dallas Quest and four from Epyx: Barbie, 9 To 5 Typing, Breakdance, and GI Joe.