Reproduced by permission of The Philadelphia Museums.

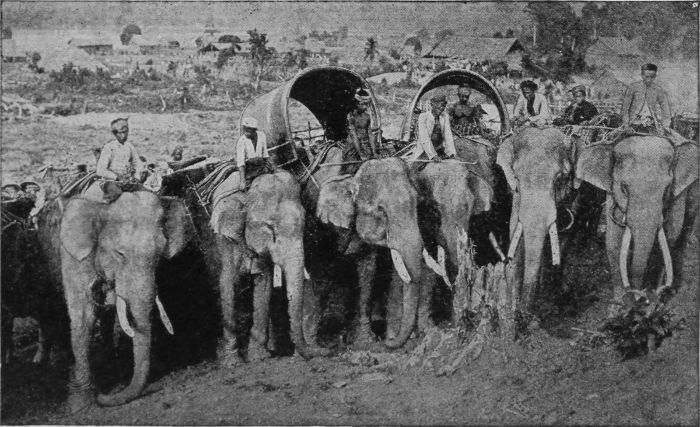

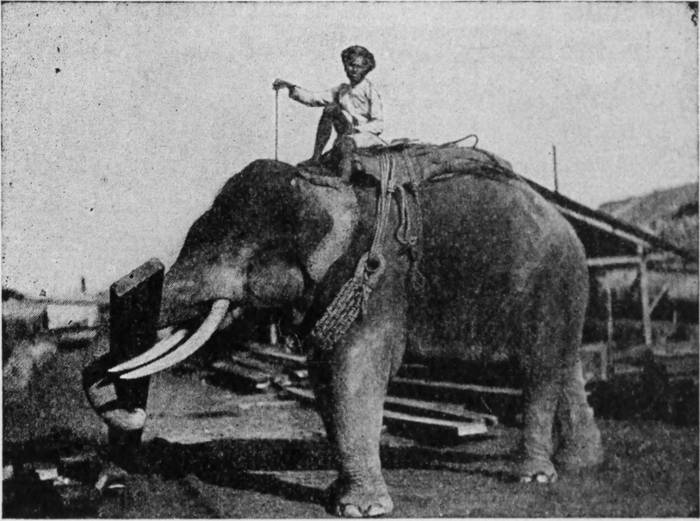

Transport Elephants, Perak, Federated Malay States

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Home Life in All Lands--Book III--Animal Friends and Helpers, by Charles Morris This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Home Life in All Lands--Book III--Animal Friends and Helpers Author: Charles Morris Release Date: July 1, 2020 [EBook #62537] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HOME LIFE IN ALL LANDS--BOOK 3 *** Produced by MFR, Karin Spence and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Home Life in All Lands

SIXTH IMPRESSION

HOME LIFE IN ALL LANDS

By CHARLES MORRIS

BOOK I

HOW THE WORLD LIVES

"It is the most intimate, and gives us the best idea of the ordinary life of these strange people to whom our author introduces us. The volume is both interesting and valuable in an unusual degree. A capital book for school or home."

—The School Journal, New York.

One hundred and twelve illustrations. 316 pages.

BOOK II

MANNERS AND CUSTOMS

OF UNCIVILIZED PEOPLES

"Excellent for school or home use. This volume deals with the manners and customs of uncivilized peoples. The illustrations are well chosen and the style is admirable."—Providence Journal.

One hundred illustrations. 322 pages.

BOOK III

ANIMAL FRIENDS AND

HELPERS

Fully illustrated. 340 pages.

J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

PUBLISHERS PHILADELPHIA

Reproduced by permission of The Philadelphia Museums.

Transport Elephants, Perak, Federated Malay States

BY

CHARLES MORRIS

Author of "Historical Tales," "History of the World,"

"History of the United States," etc.

Book III.

ANIMAL FRIENDS AND HELPERS

ILLUSTRATED

PHILADELPHIA & LONDON

J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

COPYRIGHT, 1911, BY J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

PRINTED IN UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

In the earlier volumes of this series, man, as the maker of and dweller in the home, was dealt with in the varied aspects of his existence. But man is not the only occupant of the home. He has brought around him an interesting family of animals of great variety in form and habit, many of them kept as pets and companions, many aiding him in his sports and his labors, others supplying him with meat, milk, butter, eggs and other forms of food. It is a varied and active sub-family of the household, the barnyard and field with which we here propose to deal, its inmates varying in size from the lordly elephant to the busy bee, and in intelligence from the wide-awake dog to the stupid sheep, a multitude of running, flying, and swimming forms brought together from every domain of nature and serving man in a hundred ways.

The full story of this wider family of the home would be a long one. These humbler animals have a life of their own as interesting in its way as that of man, their master and friend. We cannot tell it all in the small space at our command, but the little we have here brought together concerning the varieties and habits of our household animals must have some considerable degree of interest to readers. This is especially the case with the many stories that can be told of their powers of thought and special habits and modes of action, and the reader will find here many striking anecdotes of animal intelligence selected out of the multitude that are on record. The story of the whole animal kingdom is pleasing and instructive, and that of the domestic animals, those which have come under man's special care, is specially so, as it is hoped the readers of this work will discover. Illustrations have been secured from a large variety of sources, a number, picturing the rarer animals, being reproduced from "Chambers' Encyclopedia."

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I | Household Pets and Comrades | 13 |

| The Dog, Man's Faithful Friend | 15 | |

| The Many Kinds of Dogs | 19 | |

| Anecdotes of Dog Wit and Wisdom | 29 | |

| The Cat, our Fireside Inmate | 42 | |

| Other Four-Footed Pets | 52 | |

| II | Our Single-Hoofed Helpers | 61 |

| The Horse in all Lands | 63 | |

| Racer and Hunter | 69 | |

| War-Horse and Working-Horse | 74 | |

| The Horse Tamer | 77 | |

| The Arab and His Horse | 79 | |

| Anecdotes of the Horse | 82 | |

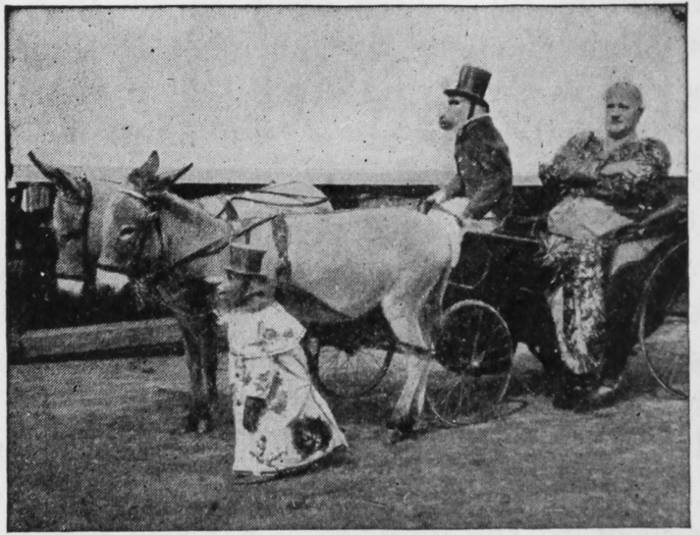

| The Ass, Zebra, and Mule | 86 | |

| III | Cloven-Hoofed Draught Animals | 92 |

| The Ox and Buffalo | 94 | |

| The Lapland Reindeer | 100 | |

| The Ship of the Desert | 102 | |

| The Dromedary | 107 | |

| The Llama and Alpaca | 111 | |

| The Arctic Beast of Burden | 113 | |

| The Elephant in Man's Service | 117 | |

| Anecdotes of the Elephant | 124 | |

| IV | Animals Which Yield Food to Man | 133 |

| The Cattle of the Field | 134 | |

| Milk-Giving Cows | 136 | |

| Beef-Making Cattle | 141 | |

| In the Bull Ring | 145 | |

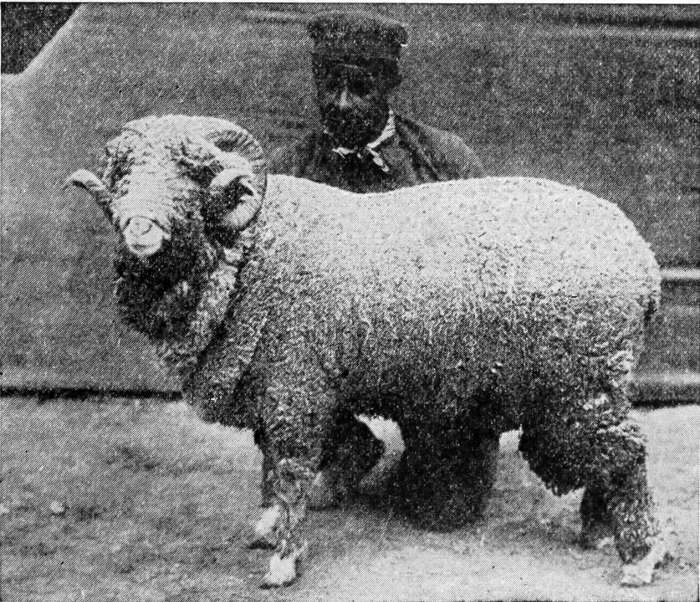

| The Wool-Clad Sheep | 149 | |

| Wool Shearing and Weaving | 156 | |

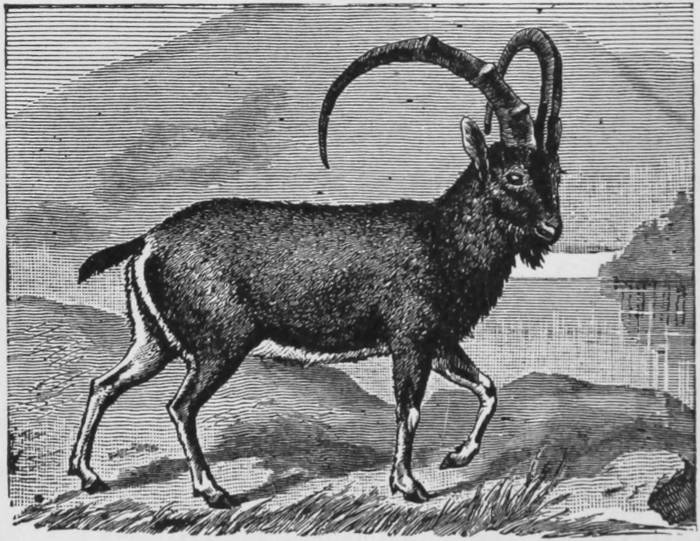

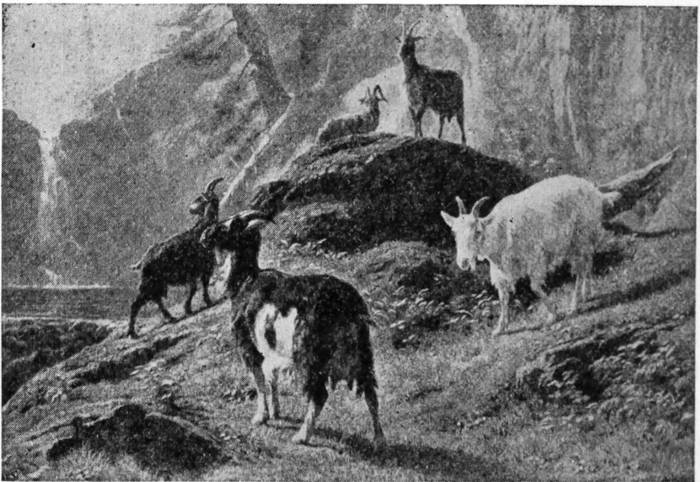

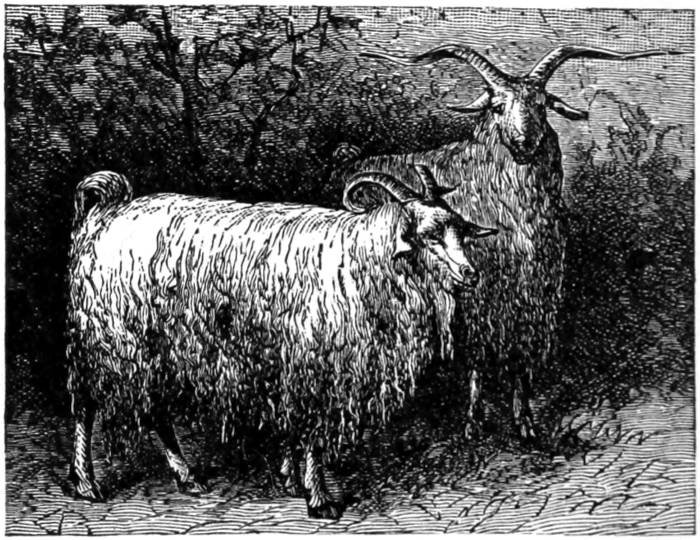

| The Bearded Goat | 158 | |

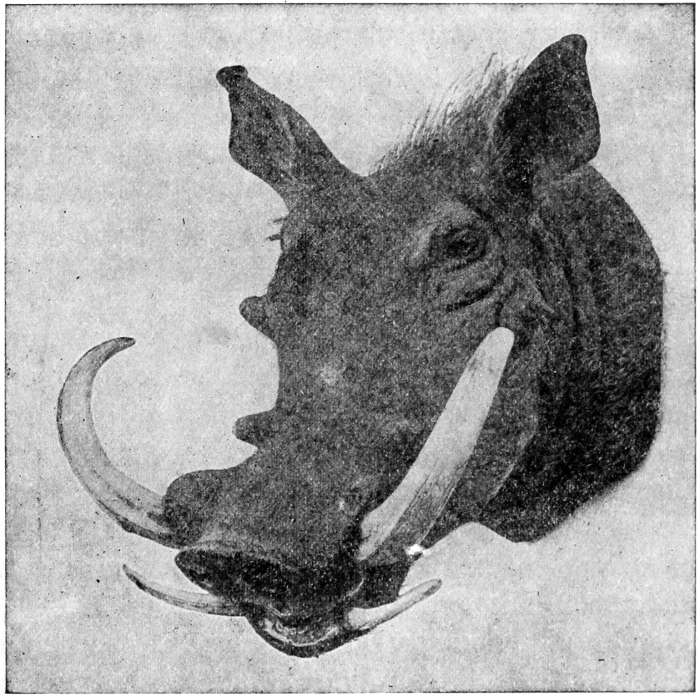

| In the Pig-sty | 165 | |

| V | The Birds of the Poultry Yard | 175 |

| The Hen and its Brood | 176 | |

| The Game-Cock and its Battles | 182 | |

| The Web-Footed Duck and Goose | 186 | |

| The Turkey and Guinea-Fowl | 193 | |

| The Swan, an Image of Grace | 199 | |

| The Proud and Gaudy Peacock | 204 | |

| The Dove-Like Pigeon | 207 | |

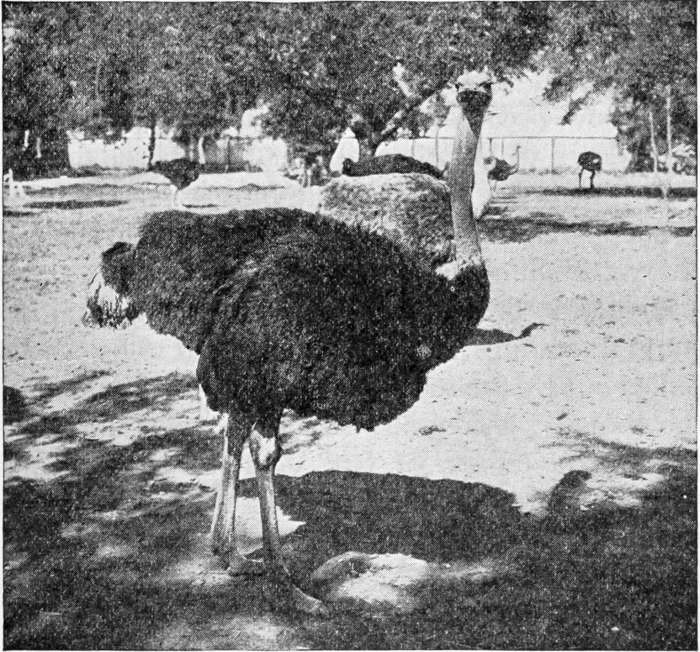

| The Ostrich and its Splendid Plumes | 213 | |

| VI | Winged and Tuneful Home Pets | 217 |

| The Canary and its Song | 218 | |

| The Marvellous Mocking Bird | 222 | |

| Other Caged Songsters | 224 | |

| The Parrot as a Talker | 230 | |

| Other Talking Birds | 236 | |

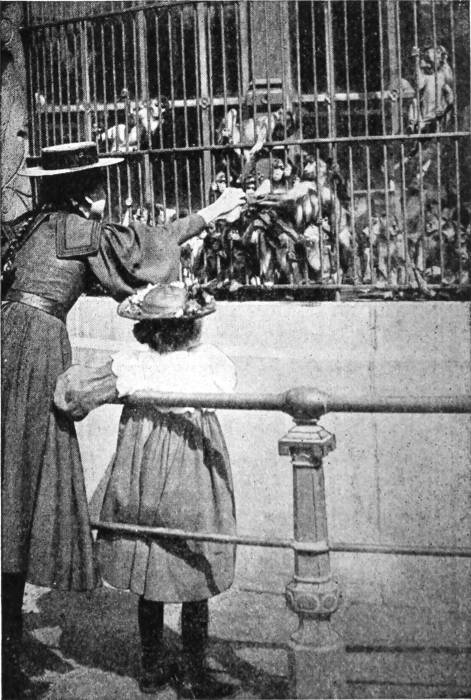

| VII | Our Cousin, the Monkey | 247 |

| The Monkey as a Pet | 248 | |

| How Monkeys Take Revenge | 250 | |

| Imitation, a Monkey Trait | 253 | |

| The Kinds of Monkeys | 259 | |

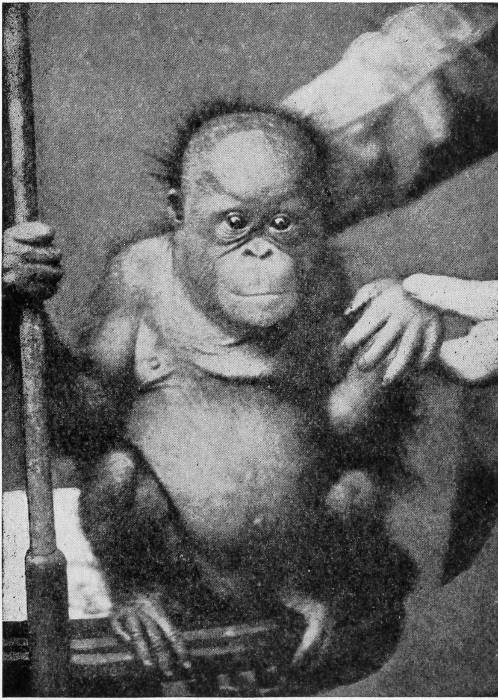

| How Monkeys Teach Themselves | 264 | |

| Anecdotes of the Ape | 270 | |

| Feeling and Friendliness in the Monkey | 273 | |

| VIII | Other Animals Used as Pets | 283 |

| Pets of the Aquarium | 286 | |

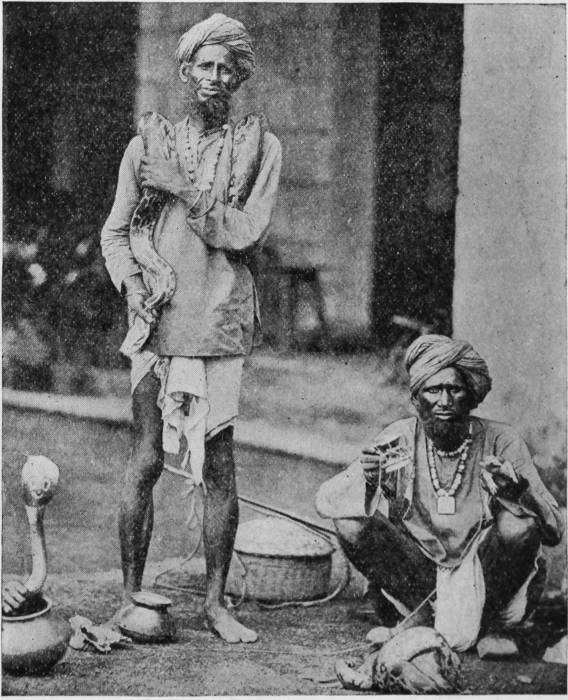

| Snake Charmers | 289 | |

| The Mongoose and other Small Animals | 297 | |

| Hawking or Falconry | 309 | |

| IX | Wild Animals in Man's Service | 317 |

| The Dancing Bear | 319 | |

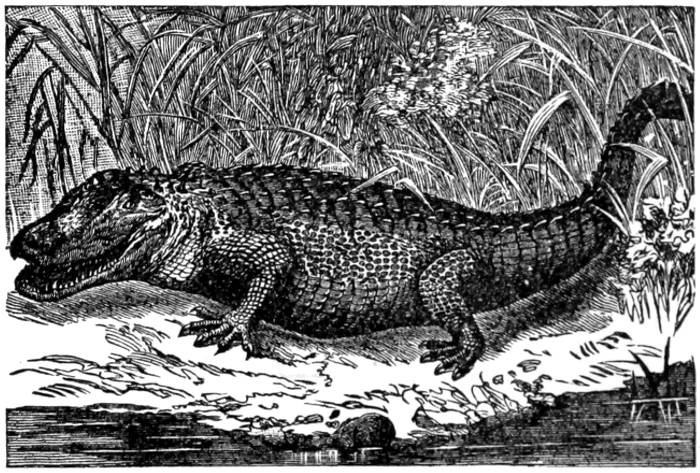

| The Seal and the Alligator | 323 | |

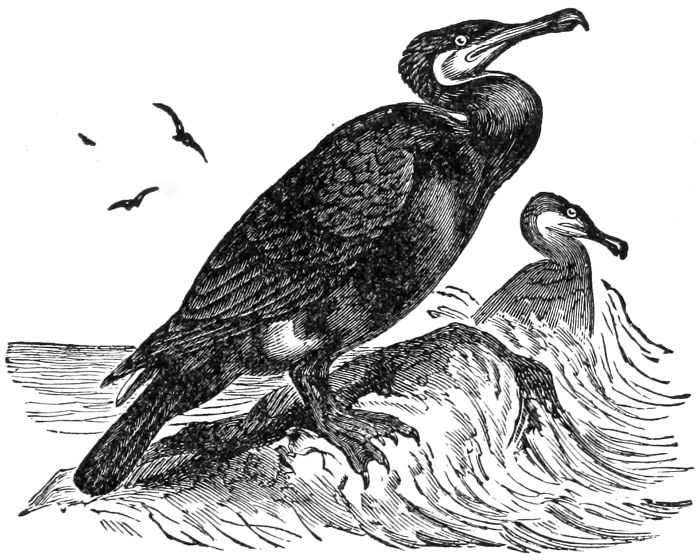

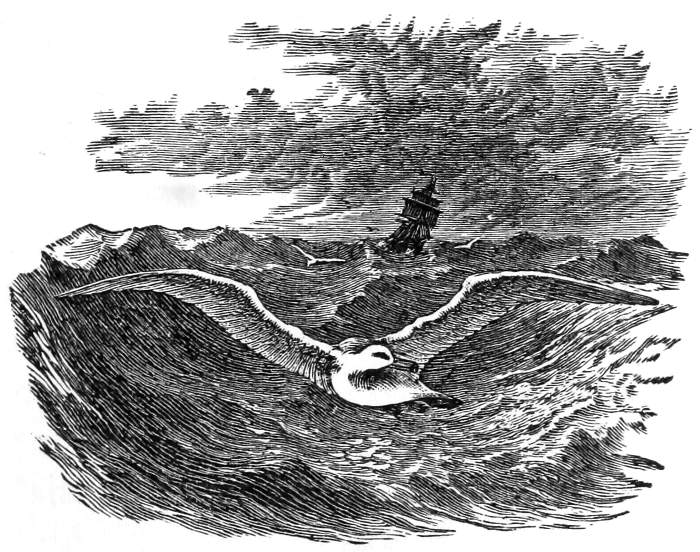

| The Stork, Cormorant, and Albatross | 327 | |

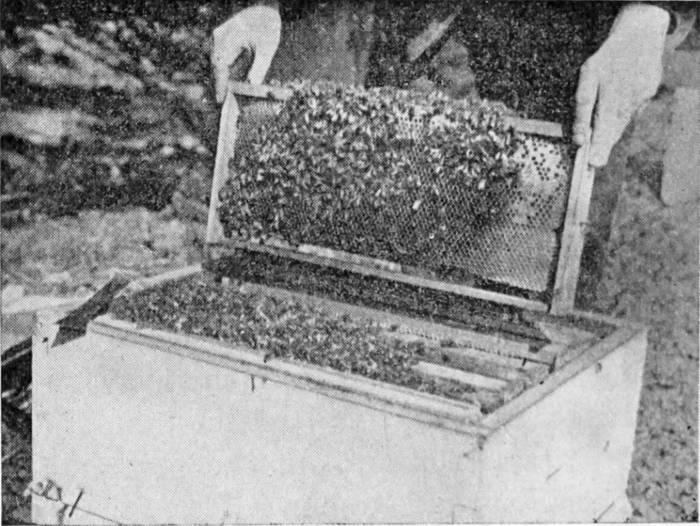

| The Honey-Giving Bee | 334 |

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

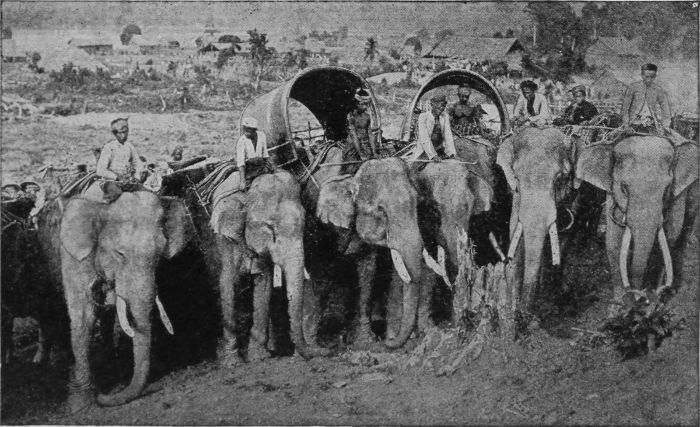

| Bird Dogs "Pointing" Partridges | 16 |

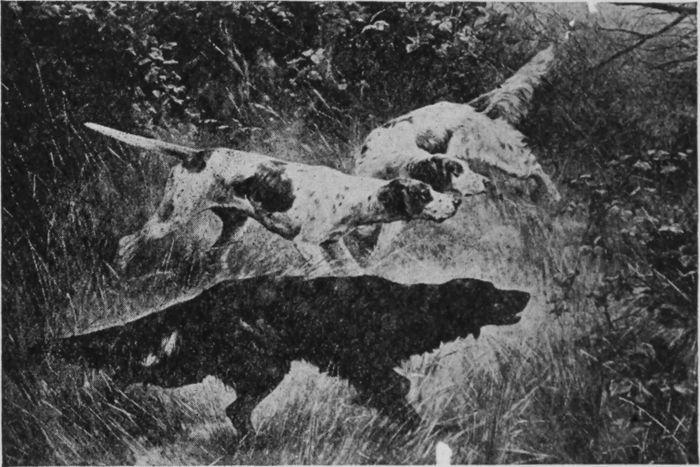

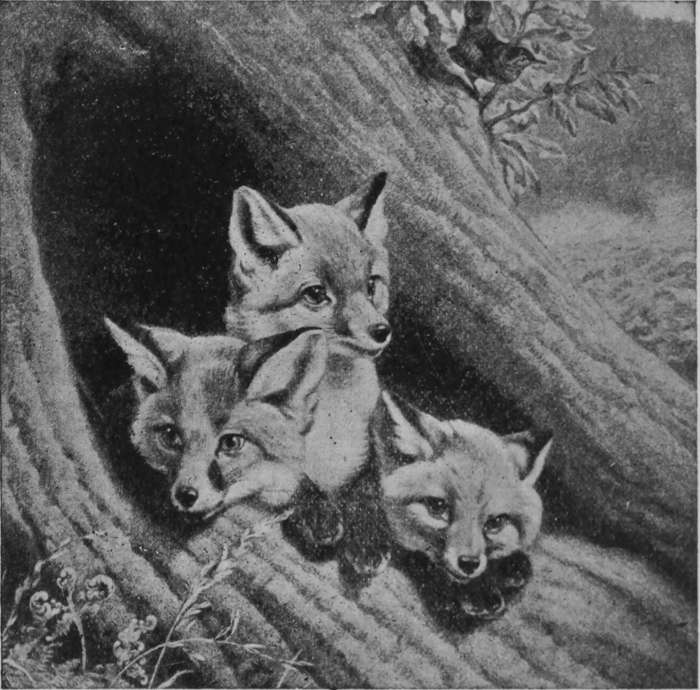

| Fox Cubs at Mouth of Den | 18 |

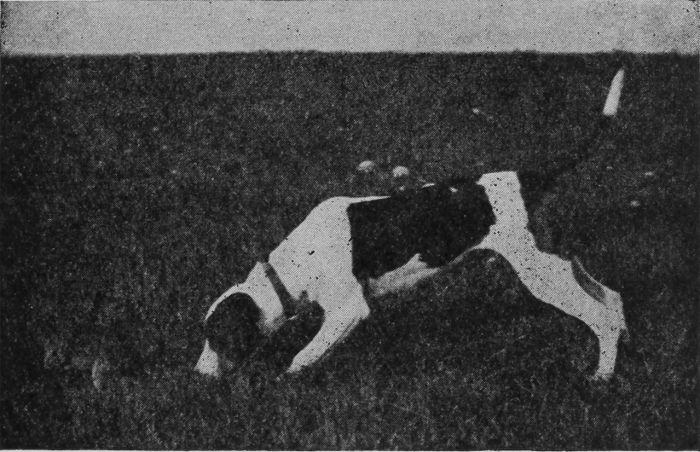

| Beagle Hound Chasing a Rat | 21 |

| Scottish Shepherd Dog Gathering His Flock | 23 |

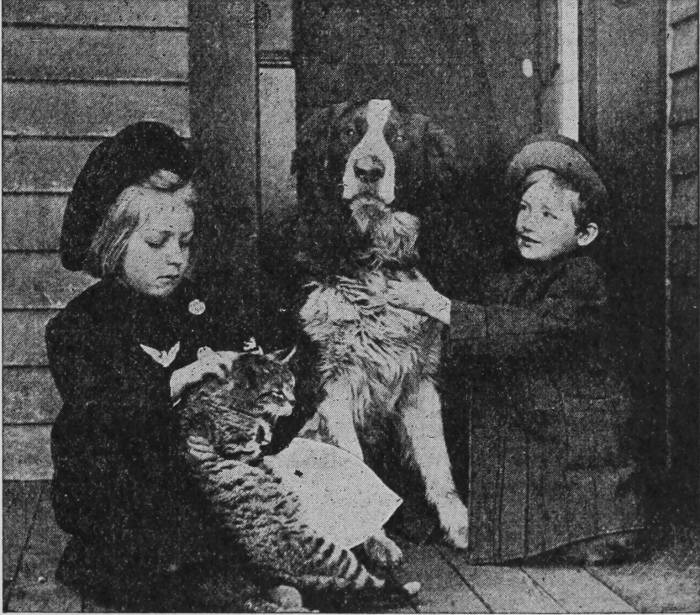

| The St. Bernard Dog and His Friends | 25 |

| A Funny Quartette of Pekingese Puppies | 28 |

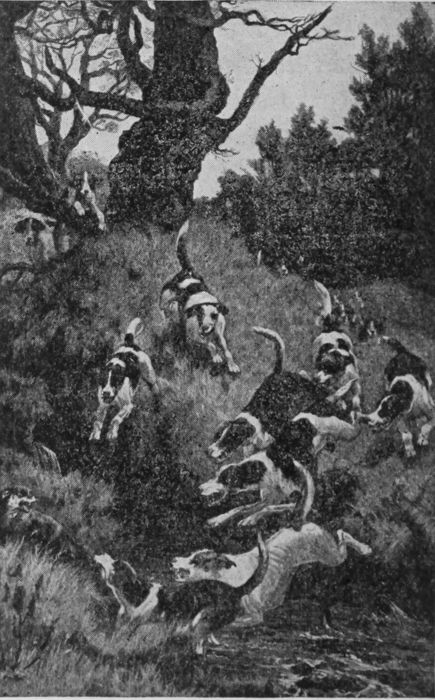

| Hounds Overtaking a Fox | 32 |

| The Dog Guardian. "Can You Talk" | 35 |

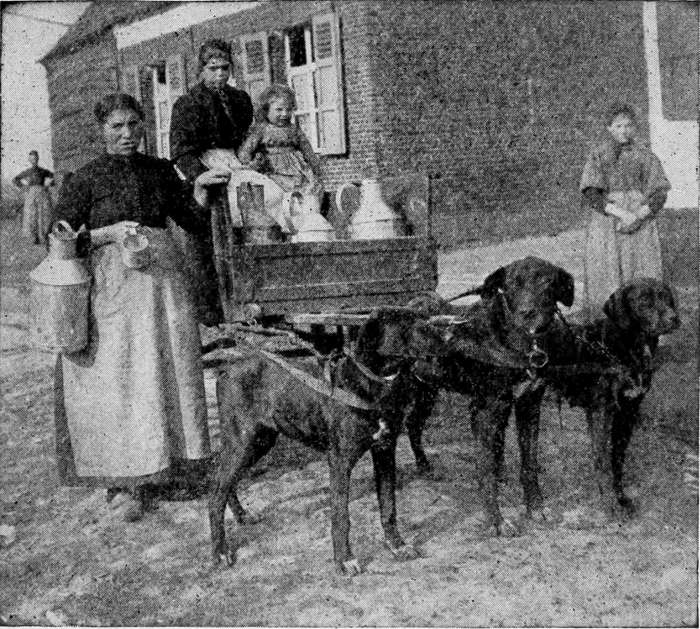

| A Dog Team Hauling Milk in Antwerp | 37 |

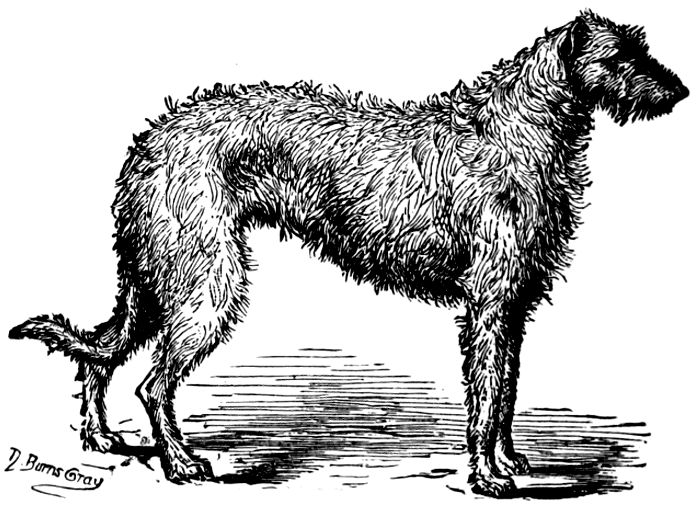

| Deerhound, Rossie Ralph | 40 |

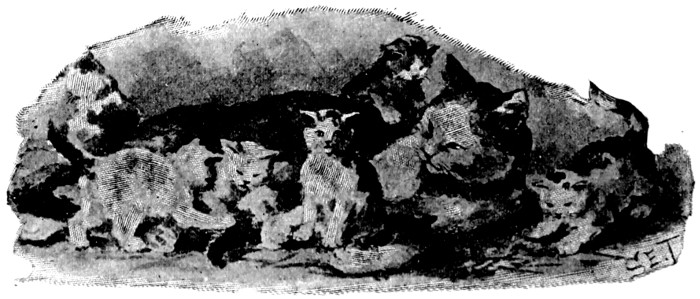

| The Mother Cat and Her Playful Brood | 42 |

| The Canada Lynx, the House Cat's "Cousin" | 45 |

| Ready for Business | 47 |

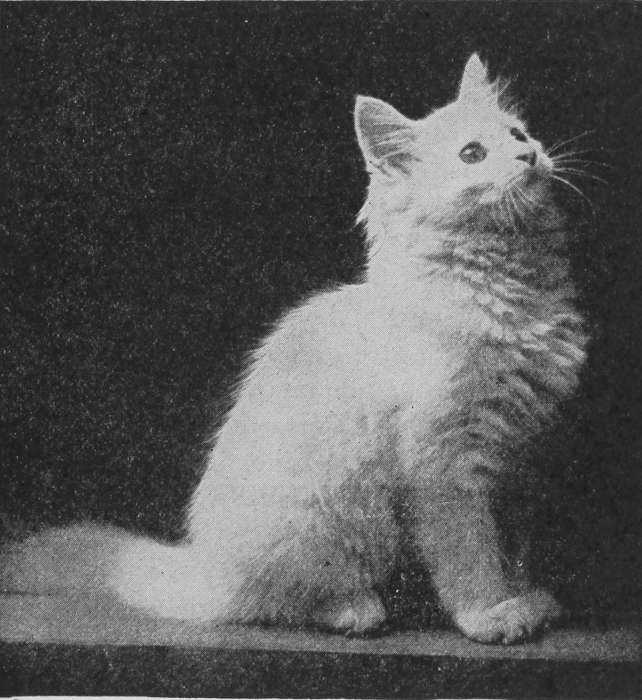

| The Hungry Babes and Playful Kitten | 51 |

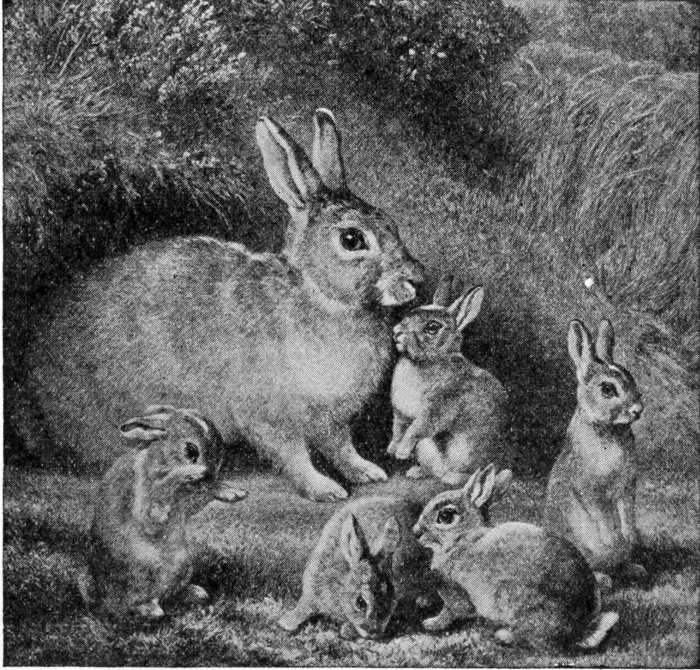

| Rabbits near Their Burrow | 55 |

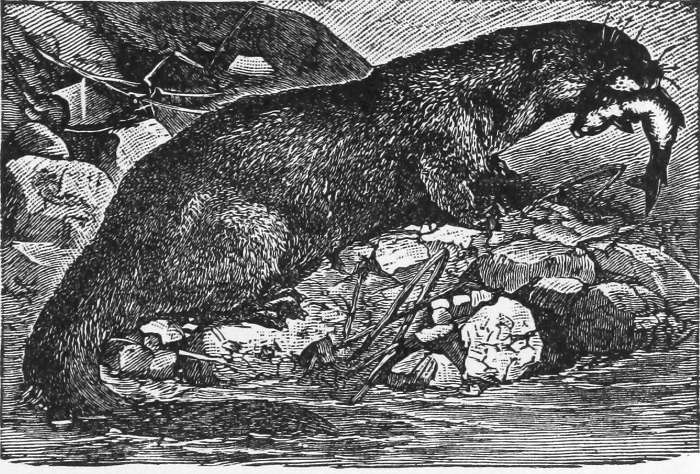

| The Otter, One of Nature's Fishers | 57 |

| A Guinea-Pig. Pig Only by Name, not by Nature | 58 |

| Friends and Comrades | 62 |

| Rosa Bonheur's Famous Picture of the Horse Fair | 64 |

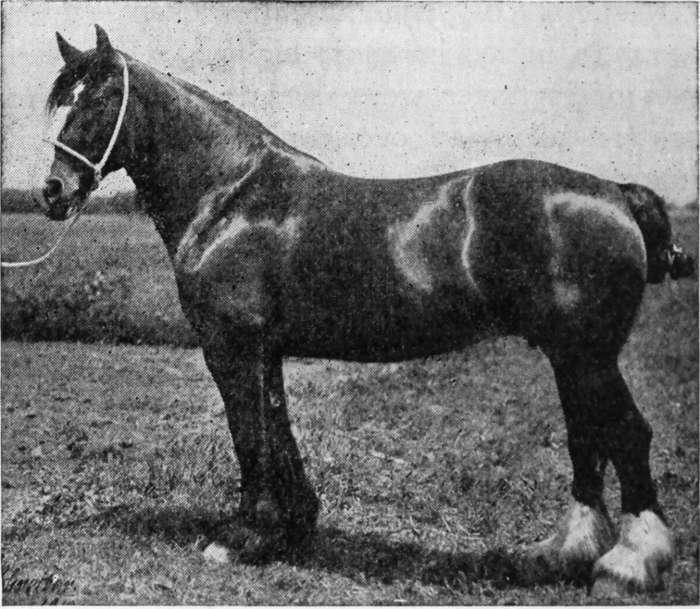

| Pure Bred Clydesdale Draft Horse | 68 |

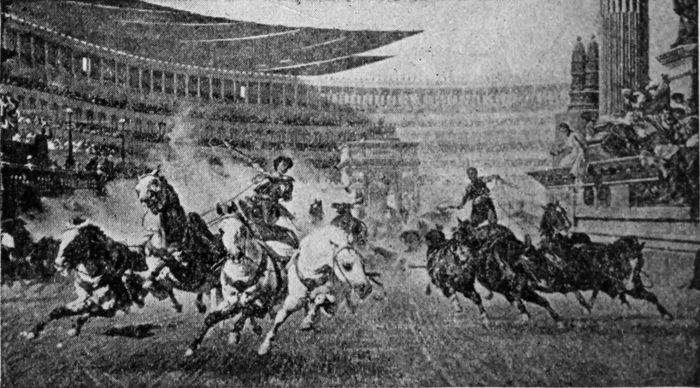

| A Roman Chariot Race | 70 |

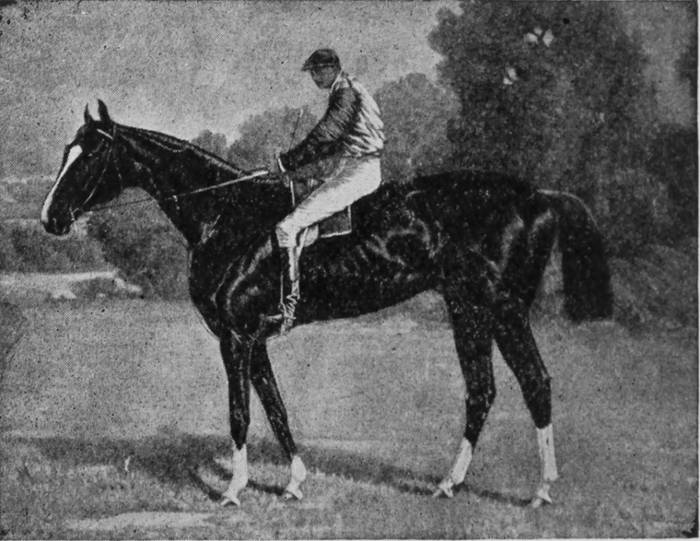

| Thoroughbred Racing Horse | 72 |

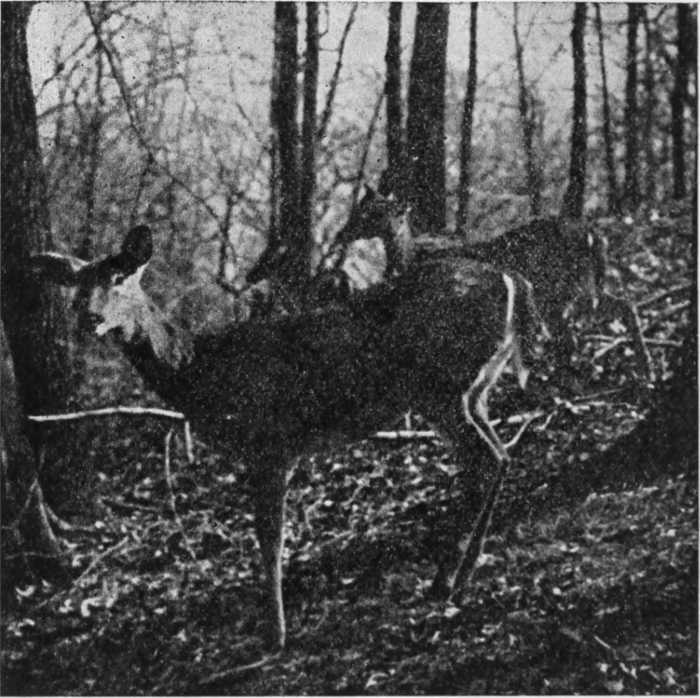

| Virginia Deer | 74 |

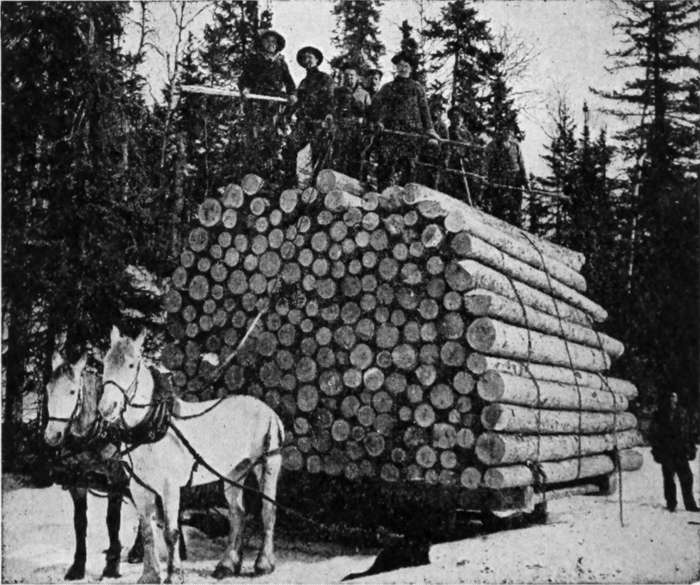

| A Logging Team with a Heavy Load | 76 |

| The Famous Arab Steeds and Desert Riders | 80 |

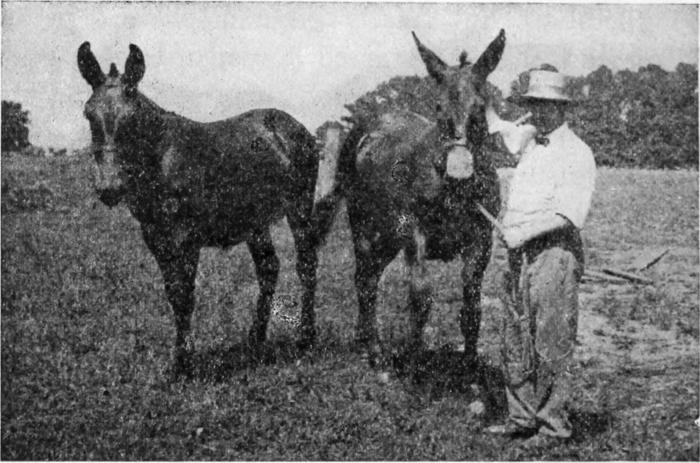

| A Pair of Prize Mules | 86 |

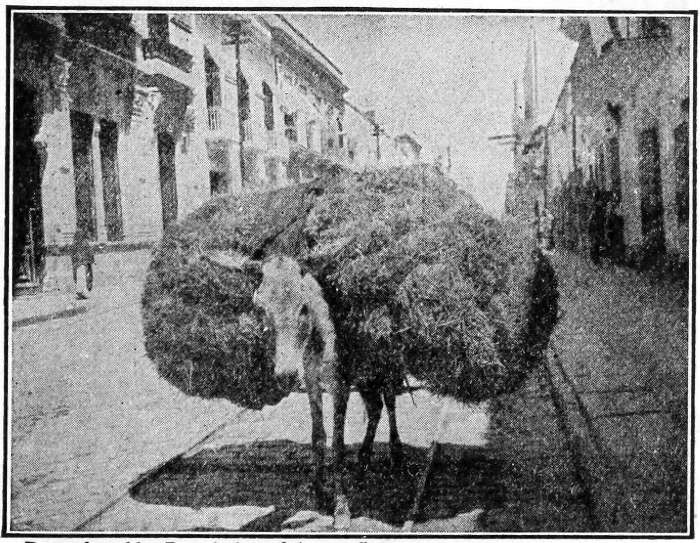

| Mexican Donkey Waiting for the Last Straw | 87 |

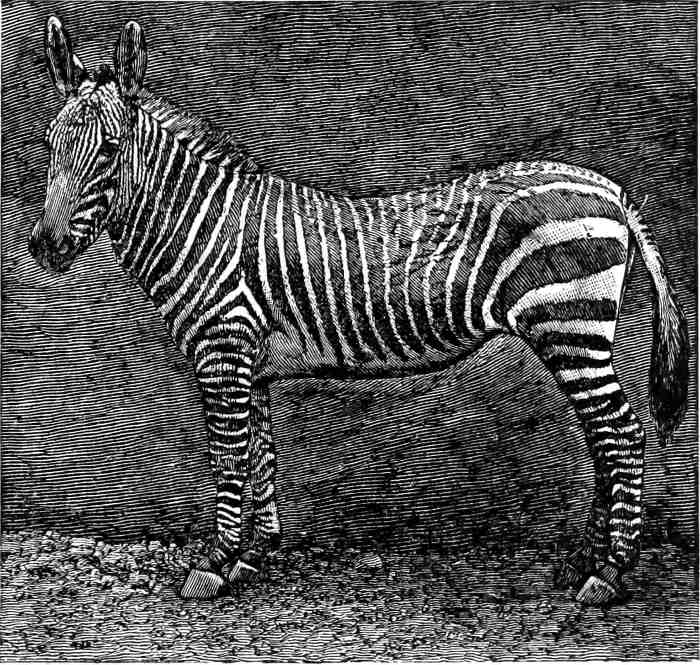

| The Striped Zebra of Africa | 89 |

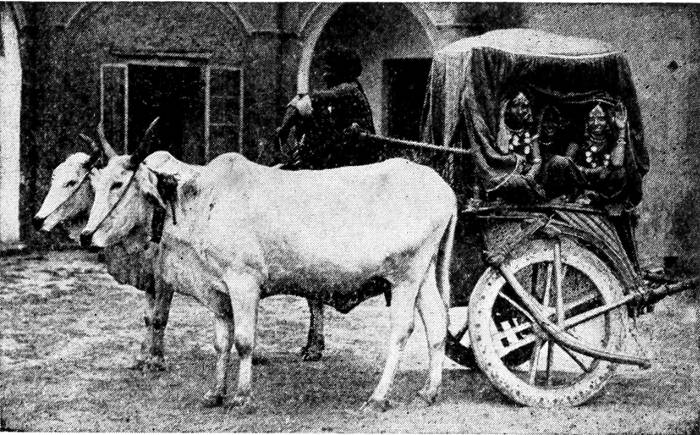

| The Native Ox Cart of Delhi, India | 93 |

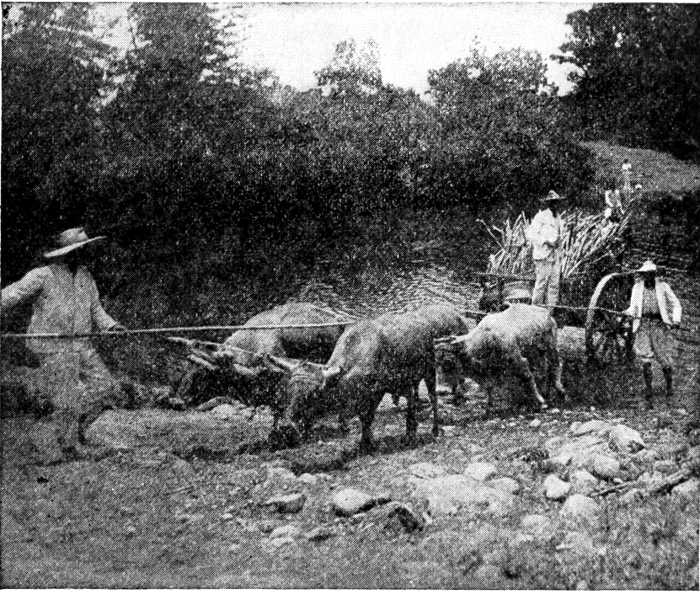

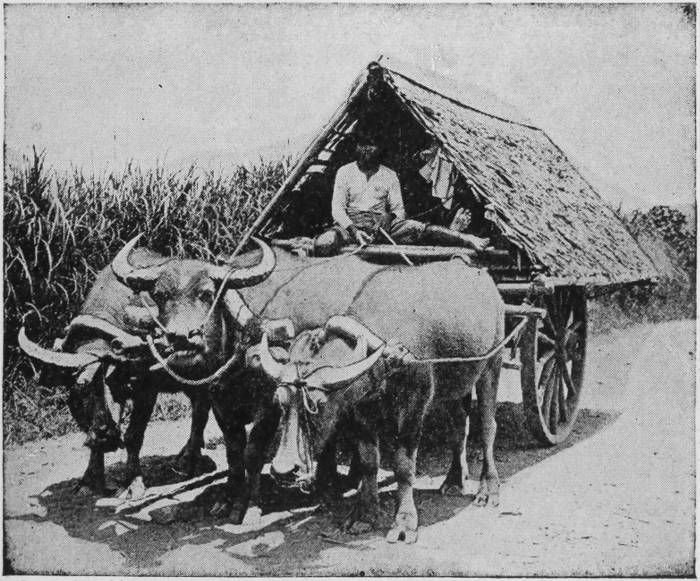

| Hauling Sugar Cane in Puerto Rico | 95 |

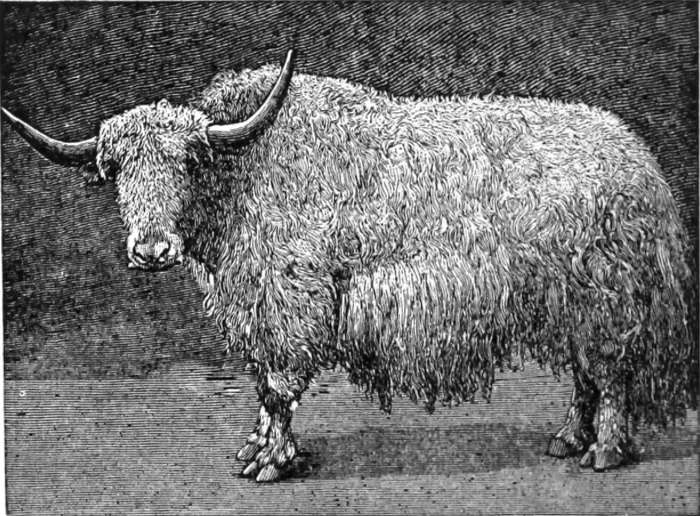

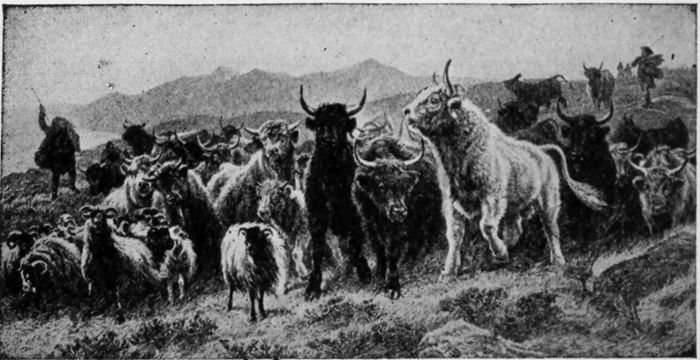

| The White Yak of the Asiatic Mountains | 96 |

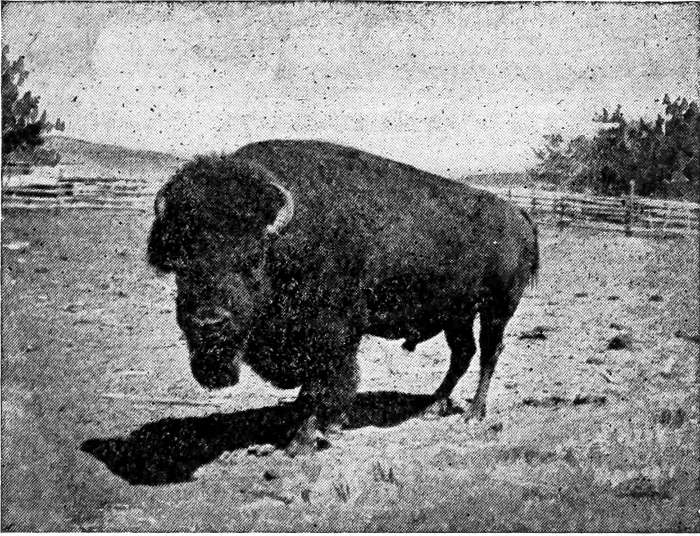

| The American Bison alone on the Prairie | 97 |

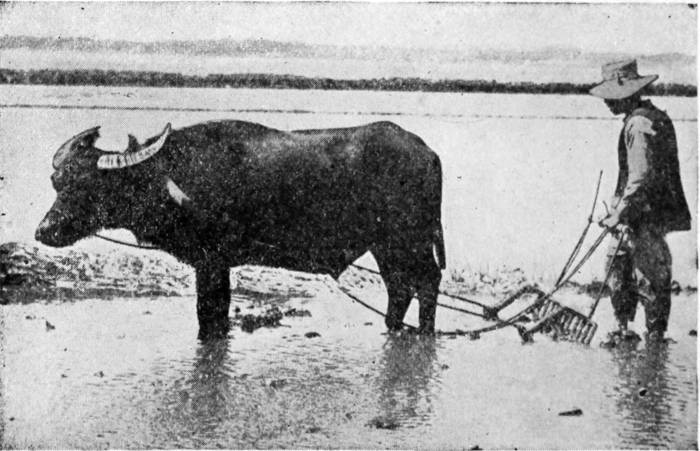

| Cultivating Rice Field with the Chinese Ox. Hawaii | 98 |

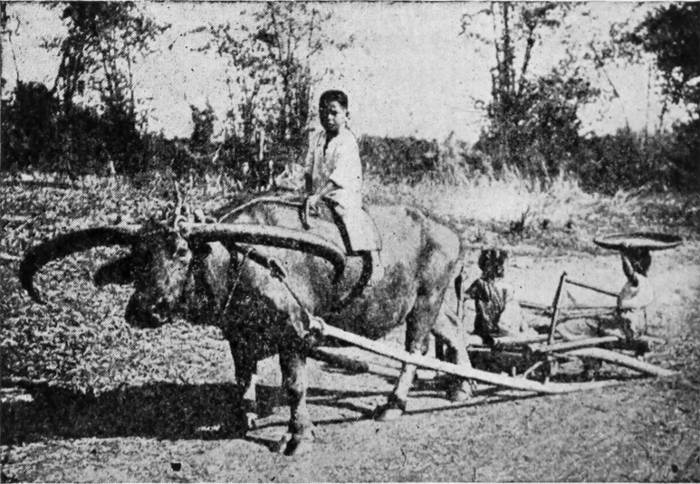

| The Carabao | 100 |

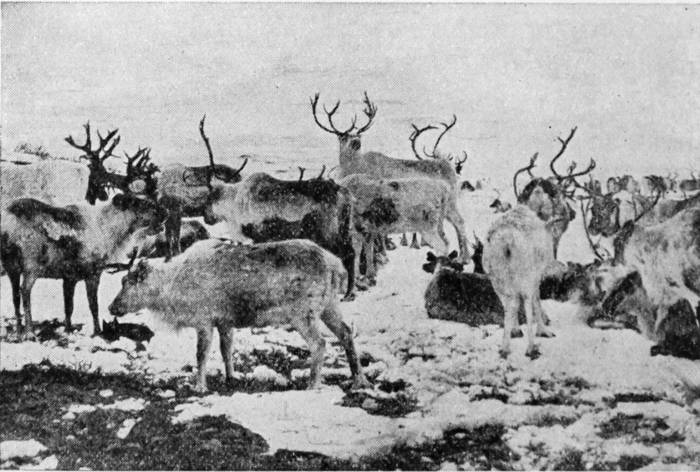

| Herd of Reindeer | 102 |

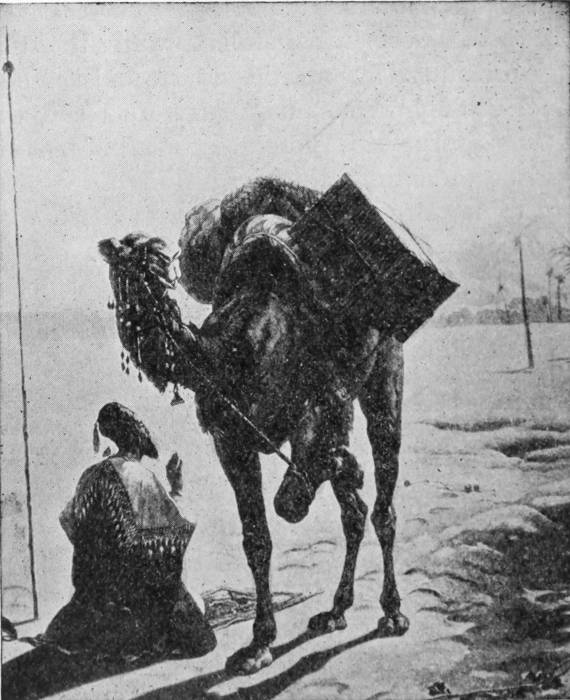

| A Sahara Desert Scene | 104 |

| A Rug Laden Caravan | 107 |

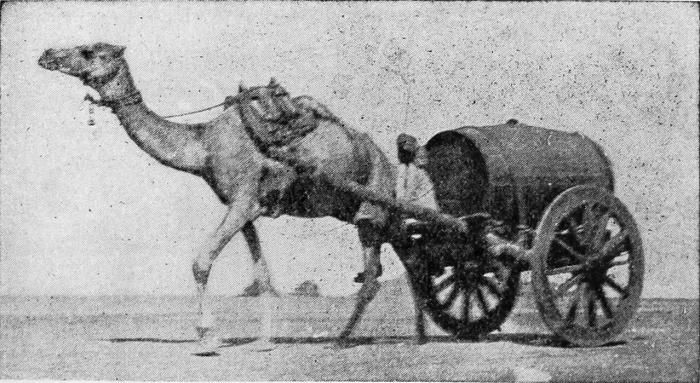

| Camel Hauling Water | 109 |

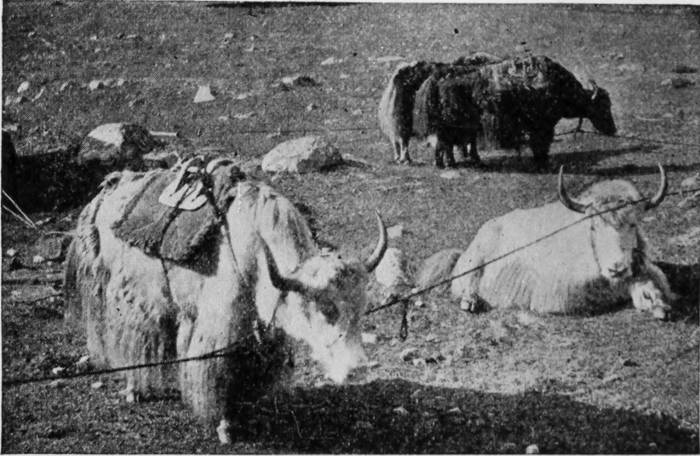

| Yaks Picketed near Camp in India | 110 |

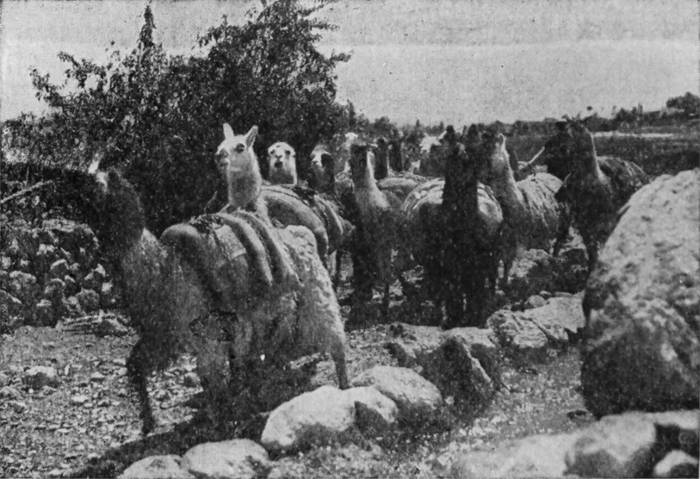

| A Llama Train Descending the Mountains of Peru | 112 |

| Dog Train Hauling Provision in Northern Canada | 114 |

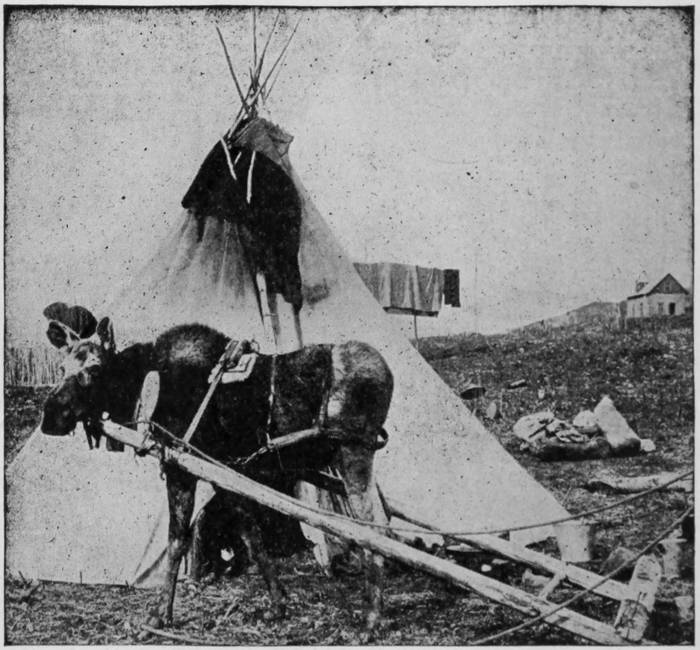

| Alaskan Dog Team—The Winter Mail Carriers | 116 |

| Elephant Piling Lumber | 120 |

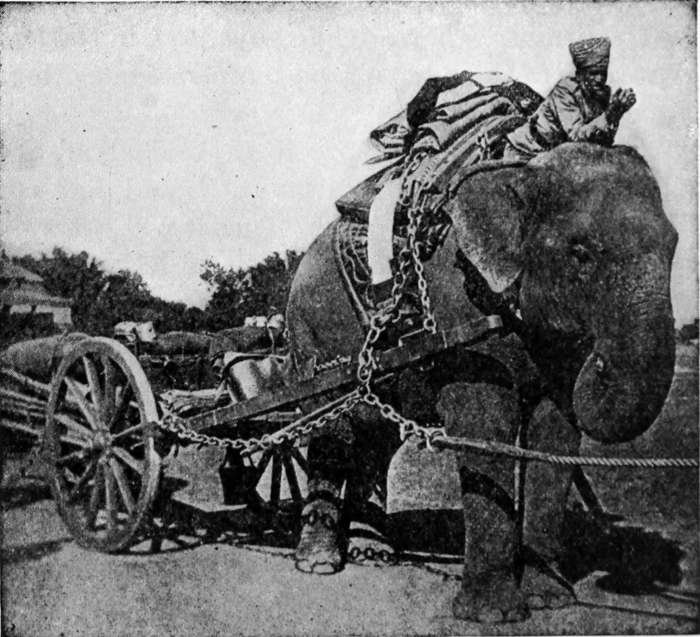

| A Military Elephant on Duty. India | 122 |

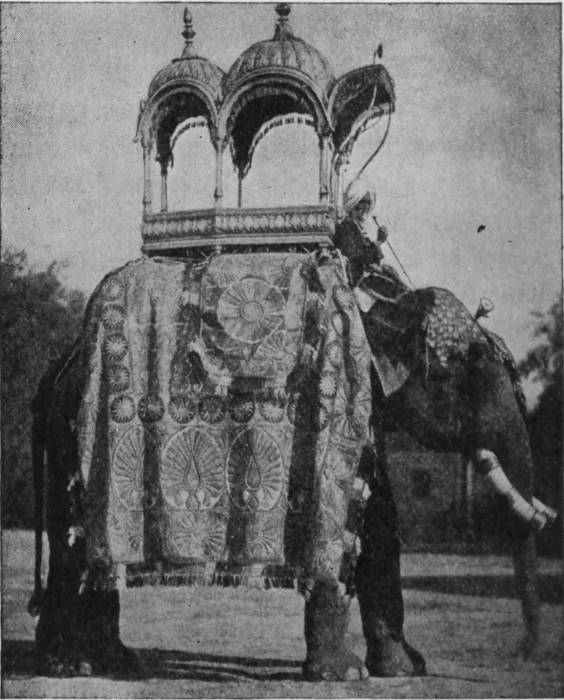

| A State Elephant of India with Howdah | 130 |

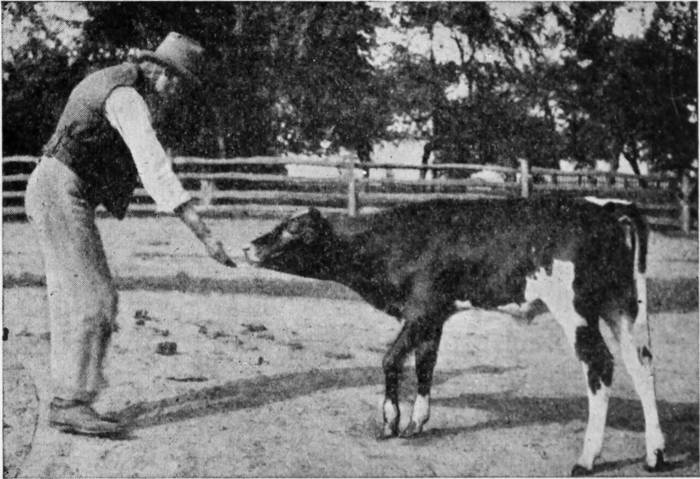

| Making Friends with a Guernsey Calf | 134 |

| Back to the Pasture After the Milking | 138 |

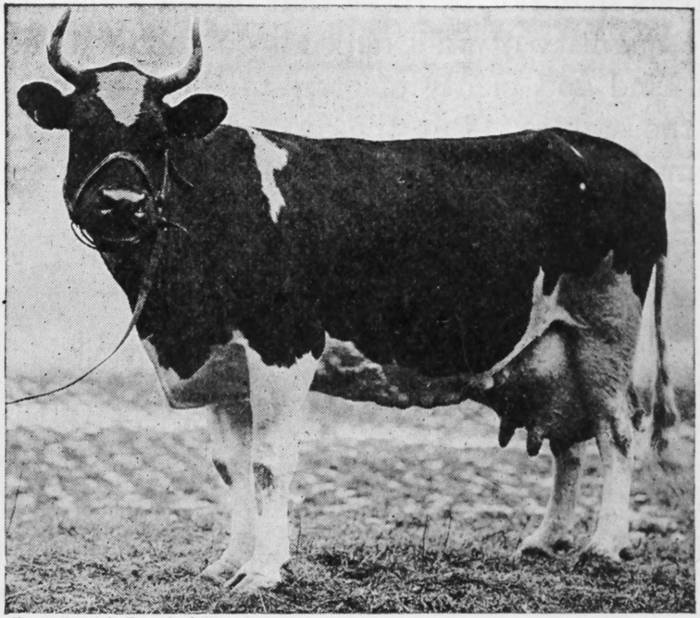

| The Holstein Cow, a Great Milk Giver | 140 |

| Ox Team and Native Cart, with Wooden Wheels | 142 |

| An Ox-Team on a Florida Plantation | 145 |

| Carting Manila Hemp. Philippine Islands | 147 |

| Moose in Harness | 148 |

| Cattle and Sheep of the Scottish Highlands | 152 |

| The Merino Ram, the Great Wool Bearer | 155 |

| The Alpine Ibex | 160 |

| Milk Goats in the Alps | 162 |

| A Pair of Angora Goats | 164 |

| The Wart Hog | 167 |

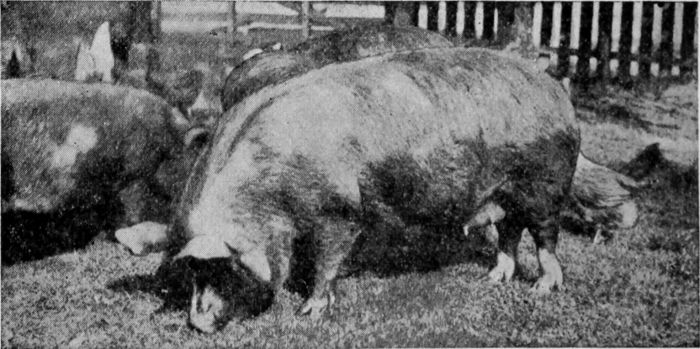

| A Fat Berkshire Hog | 170 |

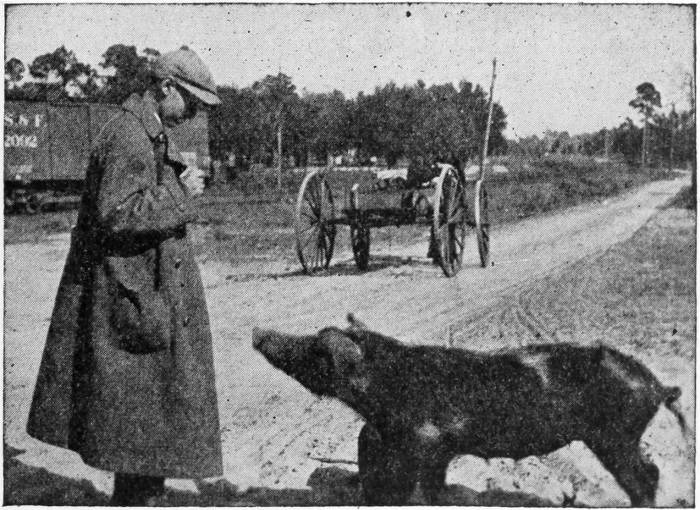

| The Razor-back Hog of the South | 173 |

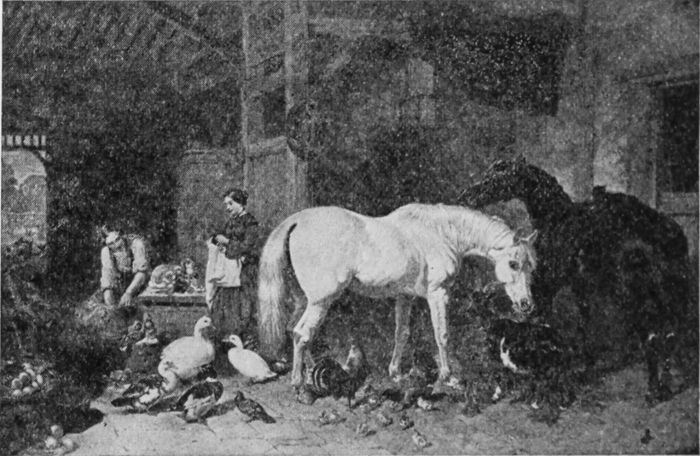

| Animals of the Farm and Poultry Yard | 174 |

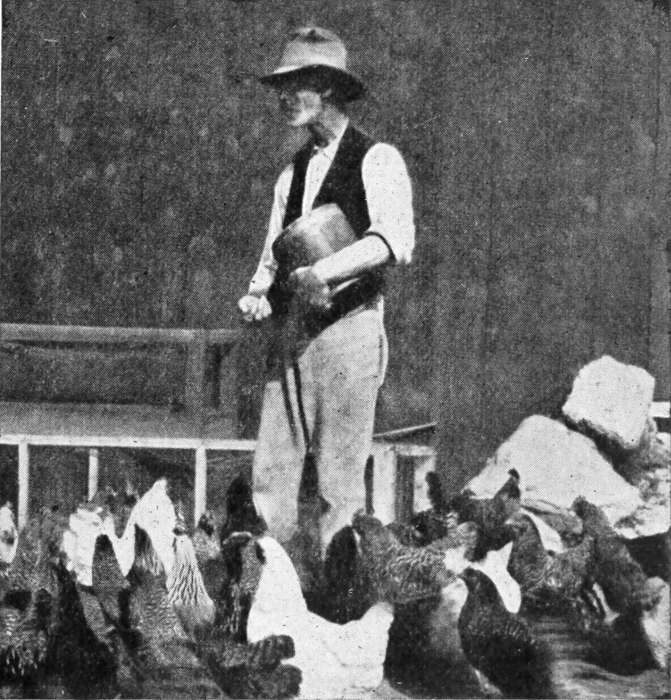

| Feeding the Chickens in the Farm-yard | 177 |

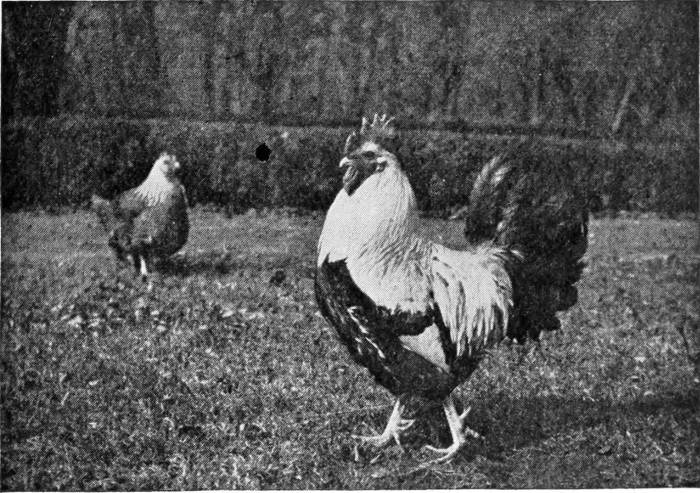

| English Dorking Cock and Hen | 181 |

| Willie and His Pet Ducks | 187 |

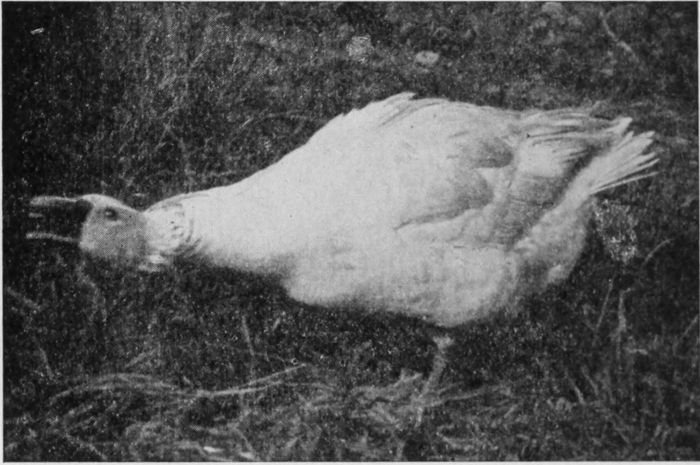

| An Assault by Hungry Geese | 190 |

| Gander Hissing at an Enemy | 192 |

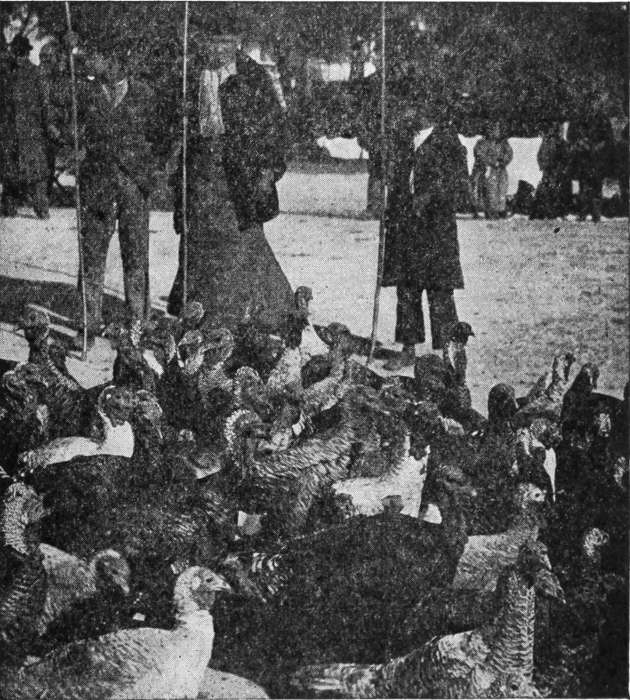

| Driving Turkeys to Market | 197 |

| The Black Swan of Australia | 201 |

| The Graceful White Swan Swimming | 203 |

| The Peacock, the Most Gorgeous of Home Birds | 205 |

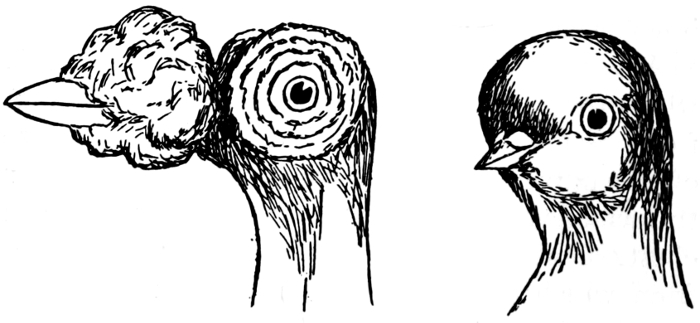

| Pigeon Types. Carrier and Short Faced Tumbler | 212 |

| On a California Ostrich Farm | 215 |

| The Mocking Bird | 223 |

| The White-Faced Parrot | 231 |

| A Gray Parrot on His Perch | 235 |

| The Starling | 242 |

| Feeding Monkeys at the Zo÷logical Garden | 252 |

| A Pair of Midget Donkeys | 258 |

| The Orang Outang in the Hands of His Keeper | 265 |

| An Afternoon Chat | 276 |

| The Fantail | 287 |

| Hindu Snake Charmers with the Deadly Cobras | 294 |

| The Mongoose | 298 |

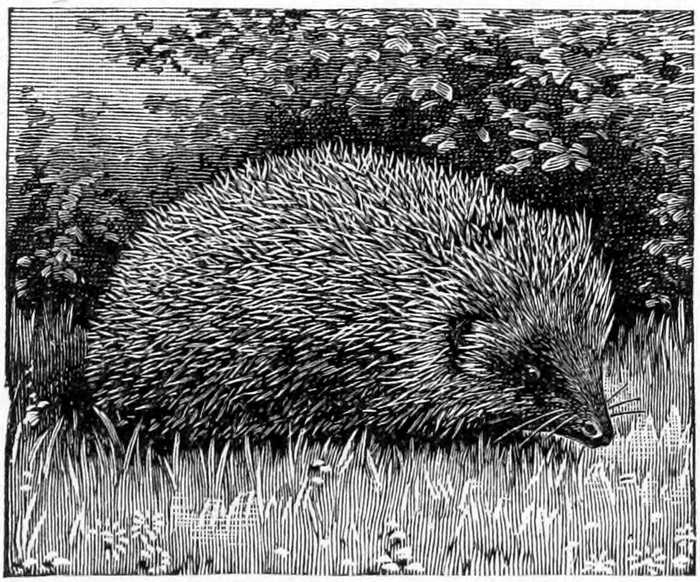

| The Common Hedgehog with His Battery of Spines | 303 |

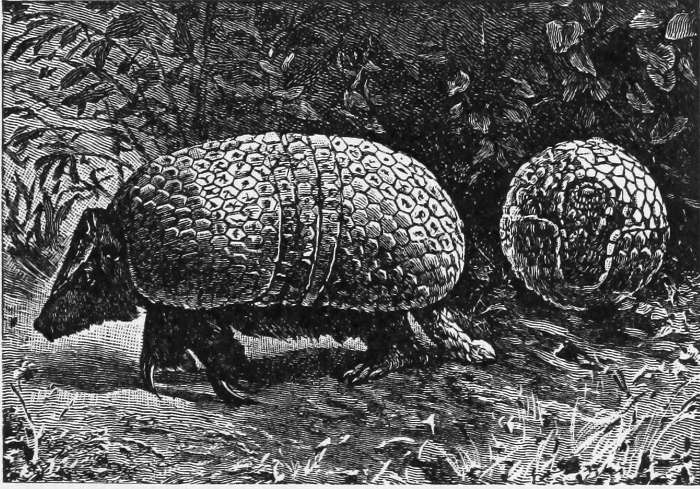

| The Three-banded Armadillo | 305 |

| A Friendly Gray Squirrel | 307 |

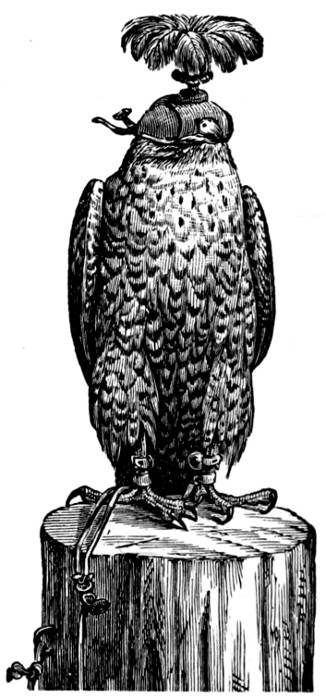

| A Hooded Peregrine Falcon | 310 |

| Leg and Foot of Falcon Showing Fastening | 314 |

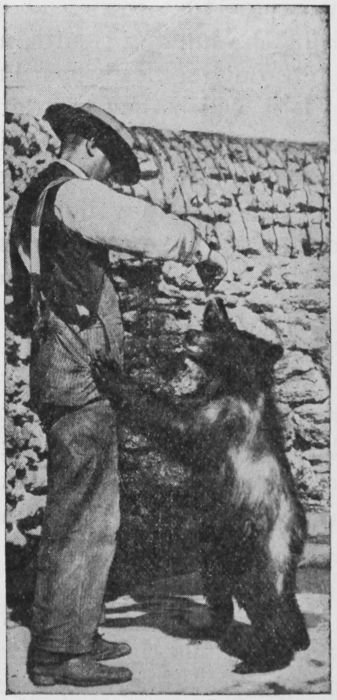

| Grizzly Bear Cub | 320 |

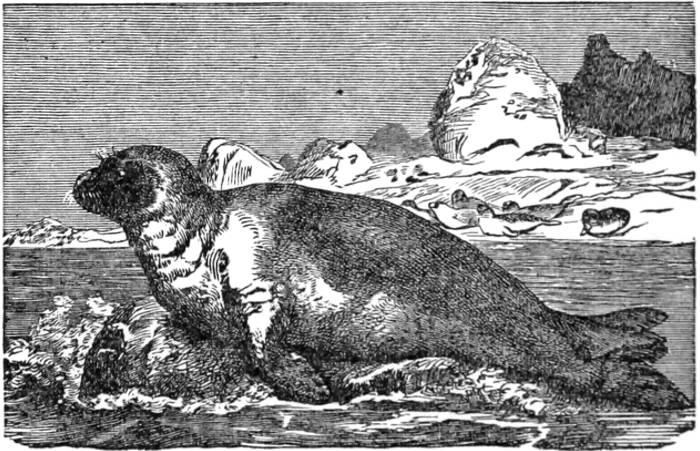

| The Harp-seal Afloat on the Ice | 324 |

| The Savage Florida Alligator | 326 |

| The Stork in Its Feeding Grounds | 329 |

| The Cormorant, the Fishing Bird of China | 331 |

| The Albatross Swooping Over the Ocean Waves | 333 |

| An Opened Bee Hive Showing the Clustering Bees | 336 |

Home Life in All Lands

How few of us can go into the house without their coming to meet us: the frisky dog, with its wagging tail; the sleek and soft-footed cat, with its mellow purr. On her swinging perch sits mistress parrot, greeting us with her noisy "Polly wants a cracker." In its gilded cage flirts the golden-hued canary, singing loudly to bid us welcome. They give life and joy to the most rustic home, these pets of the household, our glad though humble friends and guests.

If we go out of the house into the stable-yard or the pasture-field we meet others of them: the noble horse, the patient and docile cow, the woolly sheep, the sturdy goat. In the poultry-yard still others meet us: the cackling hen, proud of her new-laid egg; the crowing rooster, the quacking duck, the gracefully swimming goose or swan, the peacock with its splendid tail, even the buzzing bee, flying home laden with wax and honey.

If all our human friends should desert us, the dog would cling to us still. Carlo's faith and[14] trust were true in all the ills of life. The ragged beggar finds a loving friend in his dog. Roger the dog may be as ragged and forlorn as tramping Joe, his master; he may be a shabby mongrel of the worst breed, but a true heart beats under his rusty hide, and he will love and follow his rambling master through thick and thin.

It is the same with our petted horse, which greets us with a glad neigh and loves to kiss our hand or face with its soft muzzle. Almost any animal that we make a pet of will repay us with its love and trust, though least of all the cat, which has kept half wild through centuries of taming. But of course we cannot say this of all cats; we must give Tabby credit for some of the spirit of affection under her smooth fur, though as a rule she loves places more than she does persons and is apt to be the most independent member of the household.

If we go abroad into the wilds and woods, what shall we find there? Living creatures still, multitudes of them, but all ready to flee or fly from man. They fear him and do not trust him. If strong and fierce enough they will rush upon him instead of from him and try to kill this two-legged creature who so often tries to kill them.

But look closer and you will find that many of these wild animals are near relatives of those that man has tamed. The fierce wolf and cunning fox are cousins of the trusty dog; the terrible lion and tiger belong to the same family as the cat we[15] fondle in our laps; the zebra which no man can tame is not far away in family tree from the faithful horse. Very many more of these animals might have been tamed if man had cared to do so. But he picked out those that pleased him most or that he could make the best use of and left the others to their wild ways.

Now you may see what we are here to talk about. It is our purpose to set out on a home journey, one that starts from the kitchen or the parlor of the house and goes no farther than the outer fence of the farm—if we are lucky enough to have a farm. We are not making this home trip to call on anybody like ourselves. We are setting out to visit the cattle and sheep in their pasture-fields, the horses in their stalls, the poultry in their yards, the pig in his pen, and have a quiet talk about what we find there. And at the same time we must have our say about the dog that follows us in our round, and seems to fancy himself one of ourselves rather than one of those we are proposing to call upon. He thinks himself "folks," does master doggy. Let us take him at his own measure and deal with him first, of all.

Where did the dog come from and how long has he made man his companion? These are questions not easy to answer. Almost ever since there has been a man there has been a dog to[16] follow at his heels and aid him in his sports. If we go back far before the beginning of history we find the bones of man and dog in the same grave. And it is a strange thing that thousands of years ago there were the same kinds of dogs we see about us to-day.

Bird Dogs "Pointing" Partridges

How do we know this, you ask? Why, four or five thousand years ago the people of Egypt kept dogs, just as we do, and thought so much of them as to draw pictures of them on the walls of their tombs. If you should visit these tombs, cut deep into the rocks, you would see here the picture of a greyhound, farther on a kind of terrier, still farther one of a wolf-dog, all looking much like our own dogs. So in ancient Assyria we find images of watch-dogs and hunting-dogs, much like our[17] mastiff and greyhound. Thus, go back as far as we please in the story of human life, man's faithful friend keeps everywhere with him.

Where did he come from? That is another part of our question. We all know that the dog's forefathers must have been wild animals, hunters and meat-eaters, which were tamed by man and made his comrades. There are plenty of these wild animals still, wolves we call them, fierce hunting creatures that run down smaller animals and kill them for food. They do not bark like the dog, but they are like it in many ways. Barking is a new form of speech learned by the civilized dog. It is the dog's trade mark.

Wise men who have made a study of the dog are sure he began as a wolf, and some dogs have not yet got far away from the wolf. Have any of you ever seen an Eskimo dog, the kind that drags the sleds of travellers over the Arctic ice? If you have, you have looked upon a half-civilized creature that is as much wolf as dog. It will work well—under the whip; but its great delight is an all-round fight, and if hungry its master is not safe from its sharp teeth.

In fact, the dogs kept by savage and barbarian people look much like the wolves of the country around them. Thus the dogs kept by the Indian tribes of our land are so much like the wolves found in the same regions that it is not easy to tell them apart.

In southern Asia and parts of Africa is a wild animal called the jackal. It is smaller than the wolf, but belongs to the same family and seems to come half way between the wolf and the fox. It is fairly certain that some of the dogs of India and other countries are tamed jackals. The jackal is easy to tame, and a tamed jackal will wag its tail and crouch before its master just like a dog.

Fox Cubs at Mouth of Den. Observe Their Vigilant and Alert Outlook

We begin now to see where man found the dog. He seems in very early times to have tamed the[19] wolves and jackals around him, fed them, won their love by kindness, and taught them to do many new things. The wolves hunt in packs just as dogs do, and they are very expert in taking their prey. It is the same with the jackals. They hunt in packs like the wolves and are very shrewd and cunning. These wild animals are fierce, but so are many dogs, though in most cases the fierceness has been tamed out of our house dogs.

Any of us who go into a dog show might almost fancy ourselves in a zoological garden, for we seem to be in the midst of a multitude of different animals. It is hard to believe that the fluffy little Lapdog, not much bigger than a well-grown rat, belongs to the same family as the Great Dane, as tall as a pony and strong as a leopard. The same is the case if we bring together the slender and graceful Greyhound and the sturdy Mastiff; or compare the Collie with the Terrier or the Spaniel; or the ugly Bulldog or funny Pug with the long-headed Foxhound; or the hairy Poodle or Skye Terrier with the many short-haired breeds.

Nearly ten times as numerous as the letters of the alphabet, the dogs bewilder us with their variety, and it is not easy to believe that they all belong to the same family. Yet this is the case; they are all dogs, big and little, stout and slender, hairy or hairless alike, all one in their general[20] make-up and their habits. It is very likely, indeed, that they came from several species of wolves and jackals, yet there are certain traits of doggishness that belong to them all.

Shall we not fancy ourselves really in a dog show and walk around and look at the variety of dogs to be seen! We cannot name them all, there are too many of them, but we may take a quick glance at the prize dogs in the show. It is common to divide them into groups, such as hunting dogs, working dogs, watch dogs, sheep dogs, and toy dogs.

Of hunting-dogs there are many kinds, including the various hounds, such as the Bloodhound, Staghound, Foxhound, Greyhound, and others. These either have fine powers of scent or are splendid runners, so that few kinds of game can escape them. The Bloodhound has very acute scent and has long been known as a hunter of men. In the past it was used to hunt fugitives from justice and in our times has been often put on the track of runaway slaves.

The Foxhound has long been used in the sport of chasing the fox, large packs of them being kept in England and this country for that purpose. The Harrier, a smaller hound, is used in hunting the hare. Still smaller is the Beagle, the smallest of the hounds, but with the finest power of scent. It is a slow runner, but will keep it up for hours at a time, and seldom fails to bring down its game.

Other hunting-dogs are the Pointer and Setter, the friends of the gunner. The Pointer is so called from its habit of standing fixed when it scents game, while the Setter crouches down when the scent of game is in the air. The Spaniel is another hunting dog, much liked by sportsmen. It is a beautiful dog, with very long ears and wavy and beautiful hair, red and white in color. It is fond of swimming and knows well the art of fish-catching.

Beagle Hound Chasing a Rat

Working dogs include such kinds as the Eskimo dogs, that drag the sleds of the Eskimos and of polar explorers, and the dogs of Kamtchatka, swift, powerful animals, used for the same purpose. You have very likely read about the working dogs of Holland, which are used to pull the milk-carts of their masters. Then there is the[22] turnspit, much used in past times to turn the spit when meat was roasting before the fire. In our days there is no use for the turnspit, and not many dogs are made to work for their living. On the whole the dog is something of an aristocrat, ready for sport, keen on the watch, but not overly fond of work.

We cannot for a moment lose sight of the Sheep Dog, the Collie, as it is called in Scotland, a shaggy, wide-awake fellow, who takes better care of a flock of sheep than most men could do. He lives with the sheep, gathers them from the hills and brings them to the sheepfold when needed, and will let no prowler meddle with the woolly beasts under his care. The stranger who comes near the flock must be careful how he acts, if he does not wish to feel the collie's sharp teeth. That alert sentinel knows his duty and will stand no nonsense.

There are many varieties of the sheep dog. In Asia they have often to fight for their flocks with wild beasts and robbers, and are very strong and fierce. Some of them are shaggy, wolf-like brutes, nearly as large as a Newfoundland dog and not afraid of the biggest wolf. Dogs like these are also kept in some parts of Europe. Wise and sharp-witted creatures are the sheep-dogs, knowing and doing their business well. At a word or even a look from its master the collie will scour around the hills and dales for miles, rounding up and bringing the scattered sheep to one place.[23] And in or after the heavy snow-storms of the Scotch Highlands a dog is often worth a dozen men in saving its master's flocks.

Scottish Shepherd Dog Gathering His Flock

Then there is the Drover's Dog or Cur, belonging to the same family, black and white in color, used in driving sheep and cattle to the city markets and well trained in the art of doing this. The sheep dogs of South America are fine animals. Large flocks are kept there and left alone in the care of these four-footed keepers. Darwin, who often saw them, says: "When riding it is a common thing to meet a large flock of sheep, guarded by one or two dogs, at the distance of some miles from any house or man. It is amusing to observe, when approaching a flock, how the dog advances barking, and the sheep all close in his rear as if round the oldest ram."

Now let us take a look at the Watch Dogs, those that take charge of their master's house, or follow him in his walks, ready to fight for him whether he goes out or stays in, and to act as a sentinel or guard of honor for him at all times. The Mastiff is one of the well-known house guards, a great, strong, faithful sentinel, with heavy head and powerful limbs, bold enough to fight a bear or even a lion. The British mastiff is good-natured and will even let children play with him and tease him, but when kept tied up he often grows surly and dangerous to strangers. There is a mastiff kept in Tibet which is larger than the British one and attacks strangers as fiercely as a wolf would do.

Coming a step down we meet the Bulldog, smaller than the mastiff, and looking sour and surly enough to scare any child. Its face is twisted into an ugly scowl, and its jaws are like bars of iron. When it gets its teeth into any animal nothing can make it let go. You may burn it with hot irons and it will hold on still. We may pity any one, man or beast, in whom this black bunch of obstinacy sets its teeth. It knows well how to take hold, but not how to let go.

Coming another step down we see before us the Pug, a queer little house pet, which somehow is born with the bulldog's face but is as timid and good-natured as the other is fierce and surly. He is a funny little brute, ugly enough to turn milk sour. Yet with all his ugliness he finds loving friends.

The St. Bernard Dog and His Friends

Among the large watch dogs are the sturdy Newfoundland, which is well known to us all, the splendid, erect fellow called the Great Dane, and the noble St. Bernard, kept by the monks of the Alps to seek for and save travellers who have been lost on the mountain paths or in the deep snows. When a sudden snow-storm comes on two of these powerful dogs are sent out together, one with a flask of strong drink hanging from its neck, the other with a cloak for the freezing wayfarer to put on. If the traveller has lost his way they guide him to the convent. If he has fallen and[26] been covered by the snow, they trace him by their keen power of scent, dig the snow away, and bring the monks by their loud barking, which can be heard for a long distance in the clear mountain air.

Many of you must have seen the Dalmatian coach-dog. A handsome animal it is, white in color, but well marked with round black spots. It is not fit for hunting, for its scent is not good, but it is a welcome companion when one is out on foot, on horseback, or in his coach or carriage. Lively, clean and kindly, very active and fond of running, it makes an excellent comrade for the walker or rider.

We cannot give the names of all the dogs. There are too many of them. But it will not do to pass by the smaller ones, those used for sport or for house service. Chief among the small sporting breeds are the active Terriers, all of them brave, alert and quick in motion. These are used in hunting such small prey as the otter, the badger, the weasel and the rat. To see one of them at work in a room full of rats is to look upon a living flash of lightning. A single Rat Terrier has been known to kill a hundred rats, collected in one room, in seven minutes, one quick bite putting each rat out of business.

There are several kinds of Terriers. One of them is the Dandie Dinmont, spoken of by Sir Walter Scott in his novels, a beautiful little dog[27] belonging to Scotland. Then there is the favorite Skye Terrier, of the same country, with its very long body and short legs, half buried in its own hair. Between the Fox Terrier and the Bulldog, comes the Bull Terrier, having in it something of both its parents and able to fight as savagely as the Bulldog itself.

These are the big and the medium sized dogs, but there are many smaller ones, used as pets and some so small as to be only a size larger than the full-grown rat. These are the toy animals, pocket editions of their breeds, many of them only fit for ladies' pets, to be fed and fondled and taken out in coach or carriage for an airing. They include the Poodles, Terriers and Spaniels, the larger ones good for the hunting field, the smaller fit only for the parlor.

Of the Pug, with its ugly mug, we have already spoken, and may pass on to the spaniels, often charming little playmates. There are field spaniels and toy spaniels, the field dogs being good hunters and the water-spaniels fine swimmers. The toy spaniels are very different from the hunters and only fit to be fed and fondled. They include the pretty King Charles, glossy black in color, the Prince Charles, white with black-and-tan markings, the red and white Blenheim and the red Ruby Spaniel. There are other breeds, a popular one being the Japanese Spaniel. The toy spaniel should not weigh more than ten pounds[28] and have a short, turned-up face like a pug. With their long coats and small size they are fit only for pets, but are very bright and cheery little creatures.

Courtesy of Mrs. A. R. Bauman

A Funny Quartette of Pekingese Puppies

The Poodles may also be divided into the hunting and the pet dogs. They are fleecy fellows, often with so thick a coat of hair that it is not easy to tell where poodle begins and coat ends. The most handsome of them is the large black Russian Poodle, well fitted for use in the hunting field. The small white poodle is only fit for a house pet, but it is a very clever one and can easily be taught tricks of various kinds.

It has long been the fashion to trim the poodle's coat in an odd fashion, shaving it all off from the body and hind-quarters except a few scattered tufts, but leaving it very long and thick on the shoulders. Very likely the poodle himself does[29] not like to be made such a show of, especially if there is any bite in the air. Those who have any feeling for their dogs let the hair grow in the winter and trim it only in the warm season.

As there are toy spaniels, so there are toy terriers, among them the pretty little Black and Tan and the lovely little Maltese, with a white coat as soft as floss silk and long enough to touch the ground. These toy terriers are scarcely a handful in size, some of them weighing not more than three pounds. Then there is the graceful and beautiful Italian Greyhound; of about eight pounds weight, with soft and glossy coat, fawn and cream colored, and in every way an elegant little creature.

What could we do without the dog? There are many other animals made use of by man, but the dog, his faithful friend and companion, stands first of all. It not only aids him in his sports, but clings to him in all the affairs of life, and has been known to lie down and die on its master's grave, not willing to leave him even after death.

Not only faithful and loving is the dog, not only fond of play and sport, but it has a very good brain of its own and is one of the smartest of all the animals. If it could only talk we would find that a great deal goes on inside its little thinking organ. How wisely it will at times look[30] up in our faces, as if to say, "If I could only speak I could tell you many things worth listening to."

But can dogs think? some of you ask. I am sure that most of you who keep dogs could answer this question for yourselves. Certainly dogs very often do things that look much like thinking. There are hundreds of anecdotes telling us of wise things done by dogs and I propose to tell you some of these. I think you will find that they answer your question. I am sure that most of you could tell me of some clever dog doings. Here are some that seem worth telling.

A farmer friend of mine long ago told me of some curious things done by a dog of his. He had a bell hung on a post in his yard, with a rope coming down from it. He would ring it in the early morning to rouse up the farm hands for their day's work. One morning he was surprised to hear the bell ring very early, but no one could tell him who had rung it.

The next morning it rang again. He sprang from bed and looked out the window to find that his dog was the culprit. It had the rope in its teeth and was pulling away like an able bell-ringer. The little chap was lonely and wanted company; he had often seen the men troop out on the ringing of the bell; so he put two and two together and rang the bell himself. The farmer had to hang up the rope out of reach to put an end to this doggish trick.

The same dog had a great fancy for riding in a carriage of his own, and when one of the men drove up to the door with his cart, and left the horse standing while he went into the house for orders, doggy would bark and bite at the horse's shins until he set him in motion, and then would jump into the cart for a free ride. He was "only a dog," but he knew how to get what he wanted, and he looked proud enough as he stood with his feet on the front of the cart, as if he owned all the world he could see.

Another friend tells me that, when a country boy, he had to go a mile or two every morning to the post office for letters and papers, his dog keeping him company. On one morning there was nothing for him and he started back empty handed. But the dog refused to follow. It seated itself on the post-office steps and would not budge. He tried in various ways to make it come, but in spite of all he could do back it would go to those steps and seat itself as before.

The boy was at his wits' end. At last the thought came to him of what ailed the obstinate brute. He took a piece of paper from his pocket and held it up and at once the dog came running up, frisking about him gladly. If it could have spoken it would have said something like this: "You and I were sent to bring the papers. If you choose to go home without them I do not. I know my duty better than that."

Hounds Overtaking a Fox

The story has often been told that dogs which have been in the habit of eagerly following their masters on their week-day walks, will not stir on Sundays. They seem to know from past experience that they are not welcome on that day. Do these creatures count the days of the week and know in that way when Sunday comes? Or is there something in the dress of the family, the[33] sound of church-bells in the air, or other indications to tell them that this is a day set aside from doggish sports and duties?

All I can say in the matter is that a village friend of mine, whose church was too far away for the bells to be heard, had a dog of this kind, that ran friskily up to go out with him every morning but Sunday, when it would not stir from its rug. To test the animal he on several occasions came downstairs in his week-day clothes and went about in his week-day manner. But the wise creature was not to be fooled. It looked at him lazily and lay still, its looks seeming to say, "I can count as well as you and I know this is Sunday. You can't fool me with your old clothes."

You may see that I am not going abroad for my stories. These are not anecdotes taken from books, but little matters told me by friends. The book stories, no doubt, are better, but these are fresher. Here are one or two that I have heard of a different kind, tales which go to show the faithfulness of the watch-dog.

One of these is of a gentleman who went out one day, leaving his dog locked in the house. On his return in the evening he found that he had forgotten his key and could not get into the house by the front door. He tried the other doors and windows and at last found an open window into which he tried to climb. But so savage a bark came from the care-keeper inside that he backed out again in a hurry.

"Don't you know me, Carlo?" he said, in a coaxing tone.

Carlo knew him well enough and came with wagging tail to the window to be caressed by its master's hand. But the instant he tried again to climb in the animal's attitude changed and it became the fierce watch-dog again.

Try as he would, Carlo simply would not let him come into the house in that way. It was the burglar's route, and even if this man were his master he had no right to take it. In the end the baffled gentleman had to give up the attempt and leave Carlo lord of the premises. The faithful watch-dog knew not master or man when it came to a question of duty.

Now let me speak of a dog that had a different sense of duty. It belonged to a cousin of mine and when left in charge of the house in the absence of its mistress was quite willing to let visitors enter and seemed very glad to see them. The trouble began when they tried to go out. This the dog would not permit. It was ready to attack them with teeth and claws if they tried it. "Here you are and here you stay till my mistress comes home," its attitude seemed to say. "Your coming may be all right, but that is for the lady of the house to decide, and you shall not go a step until she returns."

Dogs cannot talk, that we all know very well. It is true that there is at present a dog in Germany[35] which has been taught to speak a number of words, in a way that makes it easy to understand them. But no one fancies that even this dog will ever become a good and ready talker. Yet it is well known that dogs can understand human speech and sometimes very well.

The Dog Guardian. "Can You Talk?"

Thus a friend of mine comes home at night, after a day's hard work, flings himself lazily on the sofa, and says to a visitor: "If Jim there knew enough I would ask him to go upstairs for my slippers."

Jim, the dog, who has been lying in easy content on his favorite spot, at once gets up, stretches himself, and trots off up stairs, coming back in a few minutes with a slipper in his mouth. Off he trots again and comes back with the other, then lies down once more with an air of satisfaction.[36] This is an actual incident. Very likely the word "slippers," joined with his own name, was the key-note to the dog's action. The two words were enough to tell him what was wanted.

Dozens of incidents of this kind might be given. Here is a good one that has so often been told that many of you may have read it. A sheep-dog in a Highland cottage was lying one day before the fire while his master, a shepherd, was talking with a neighbor. He wished to show his friend how quick-witted a dog he had, and while talking about a different matter, said in a quiet tone, "I'm thinking, sir, the cow's got into the potatoes."

The dog, which had seemed asleep, at once jumped up, leaped through the open window and scrambled to the cottage roof. Here it could see the potato field. As no cow was there, the dog ran to the farm-yard, where it found the animal it sought. It then came back to the house, and quietly lay down again.

Some time later the shepherd said the same words and the dog sprang up and went out again. But when the words were repeated a third time the wise creature came up to its master with wagging tail, and looked into his face with so comical an expression that the talkers broke out into a loud laugh. Then with a slight growl, the dog laid down again on the hearth rug with an offended air, as if saying to itself, "You shall not make a fool of me again."

A Dog Team Hauling Milk in Antwerp

This is one of the stock stories of dog wit. Many others like it might be told. There is no doubt that dogs have ways of making their dog friends know things they would like to have done. Many stories could be given to prove this, but most of them are too long to be told here. Thus we are told of dogs that have got the worst of it in a fight seeking a stronger friend, telling their story in their own way, and the two going out together to whip the whipper.

Dogs have their feelings, too, and can easily be[38] insulted. "Low life" dogs are so used to being cuffed and kicked that a kick does not hurt their feelings, though it may their flesh. But "high life" dogs are apt to be very delicate in their feelings, and the mere touch of a whip hurts their pride deeply. Here is a story of a Skye terrier that went out every day for a walk in the park with its master's brother. One day when it hung back to amuse itself with another dog the gentleman, to induce it to follow, struck it with his glove.

The terrier looked up with an air of anger and dignity, turned round and trotted off home. The next day it went out again, but after a short walk it looked up into the man's face, turned on its heels, and trotted back once more with an air of great dignity. Having thus made its protest, it would never go out with him again.

Here is another case, having to do this time with unjust treatment instead of offended pride. Arago, the famous French scientist, was once detained by a storm at a country inn, and stood warming himself by the kitchen fire while the innkeeper roasted a fowl for his dinner.

Having put the fowl on the spit over the fire, the innkeeper tried to catch a turnspit dog lying in the kitchen and put him in the wheel by which the spit was turned. But the dog would not enter the spit, got under a table, and showed fight. When Arago asked what made it act that way,[39] the host said that the dog was right, it was not its turn but that of its companion, then out of the room. The other turnspit was sent for, entered the wheel at once and turned away willingly. When the fowl was half done Arago took this dog out and the other dog now readily took his turn. He had fought for right and justice and had won.

We must stop here. The stories told about the intelligence of dogs are so many and of such different kinds that they would more than fill this book if all were told. We have picked out a few of some kinds. There are other kinds. Thus dogs do not like to be laughed at. They have also some sense of humor and will try to play tricks on their masters. They have a sense of shame and will slink away when caught at some act of which they should be ashamed. And there are thieves among them that will steal in a very skilful manner. Thus sheep-killing dogs are very cunning at hiding the evidence of their nightly raids in the sheep-field.

I cannot leave the dog without quoting Senator Vest's fine words of praise of this noble animal. They may be viewed as a classic tribute to the dog. They were spoken in a law-suit in which the Senator was acting for a party whose dog had been killed. It was "only a dog," said the other lawyer. Here is what Senator Vest said to the jury:

"Gentlemen of the Jury: The best friend a[40] man has in the world may turn against him. His son and daughter whom he has reared with loving care may become ungrateful. Those who are nearest and dearest to us, those whom we trust with our happiness and our good name, may become traitors to their trust. The money that a man has he may lose. It flies away from him when he may need it most. A man's reputation may be sacrificed in a moment of ill-considered action. The people who are prone to fall on their knees and do us honor when success is with us may be the first to throw the stone of malice when failure settles its cloud upon our heads. The one absolutely unselfish friend a man may have in this selfish world, the one that never deserts him, the one that never proves ungrateful or treacherous, is the dog."

Deerhound, Rossie Ralph

"A man's dog stands by him in prosperity and poverty, in health and sickness. He will sleep on the cold ground when winter winds blow and snow drives fiercely, if only he may be near his master's side. He will kiss the hand that has no food to offer; he will lick the wounds and sores that come in encounters with the roughness of the world. He guards the sleep of his pauper master as if he were a prince. When all other friends desert, he remains; when riches take wings and reputation falls to pieces, he is as constant in his love as the sun in its journey through the heavens. If fortune drives the master forth an outcast into the world, friendless and homeless, the faithful dog asks no higher privilege than that of accompanying him to guard against danger, to fight against his enemies. And, when the last scene of all comes and death takes his master in its embrace, and his body is laid away in the cold ground; no matter if all other friends pursue their way, there by his graveside will the noble dog be found, his head between his paws, his eyes sad but open in alert watchfulness, faithful and true even unto death."

The claim for the loss of the dog had been $200, but when the jury heard this just and masterly tribute to the dog they gave a verdict of $500. Well they knew that every word of it was true.

When the sun has left the sky and night flings its dusky cloak over all things out-of-doors, then within the house we draw the curtain, light the lamp, and gather round the study table with books or games. And soon from her fireside nook steals up soft-footed puss, seeking a friendly lap in which she may nestle and purr the hours away.

From Trueblood's Cats by the Way

The Mother Cat and Her Playful Brood

This bundle of fur we call by the short name of cat was born in other climes and trained in other ways than the dog, and is as sly and sleek as the dog is rough and boisterous. It knows how to make itself at home and dearly loves a soft spot, but it has never quite got rid of its wild-life ways and is often as hard to make a friend of as the dog is easy. Rarely does it follow at man's heels in the dog's faithful fashion.

When did man first take the cat into his house[43] and make it one of his pets? That is hard to say. If we go back to the early days of civilization we find the cat an inmate of man's house as well as the dog, and quite as much at home. It was kept in Egypt several thousand years ago and thought so much of in those far-off days as to leave the dog almost out of sight.

The people of that old land loved and worshiped the cat, made it into a mummy when it died, and any one who killed a cat was punished as if he had committed a great crime. That was the golden age of the cat, for one of the goddesses was said to have a cat's head, and the cat had a sacred city of its own, the city of Bubastis, where a festival in its honor was held every year and attended by more than half a million of people.

The people of Greece and Rome also thought much of the cat—perhaps because it helped them to get rid of the rat, which was as great a pest then as it is now. In later Europe also the cat was a favorite, and it was the custom at Aix, in Provence, to get the finest male cat that could be found, dress it like a baby, and seat it in a splendid arm-chair for the people to bow down to and worship.

The time came at length when the cat lost its good name and people began to look upon it as an imp of evil and the companion of the witch and the sorcerer. A black cat was the worst of all and its life was a hard one. In those evil days[44] for the cat it became the fashion to fling cats from the tops of high towers, and at Metz, at the festival of St. John, cats were thrown by the dozen into a blazing fire and burned alive.

But better days have now come to pretty puss, and she is cared for as much as the dog, making the house her nest while the dog lives largely out-of-doors. It is chiefly at the late hours of the night that the cat goes abroad. I need not tell any of you what follows. You have all heard the music of a cat concert and felt as if you would like to treat those midnight howlers as the witch-cats were treated of old. Caterwauling we call it, and of all the noises of the night it is far the worst.

Where did the cat come from? That no one can tell exactly. There are wild cats in many parts of the world, we find them in Asia, in Europe, in Africa, in America, but none of them just like our household cat. The fact is that cats differ in different parts of the world and they may have come from several species. The Gloved Cat of Nubia comes nearest to the house cat in size and the shape of the head and tail, but in other ways is unlike it. So, on the whole, we are still in the dark about the origin of the cat.

One thing we do know, and this is that the cat has kept more of its wild ways than the dog. In its nightly rambles it is like the wild-cat of the woods. And even in the house it is a little too ready to show its claws. It will scratch where a[45] dog would not think of biting. It is said that the cat loves places much more than it does people, and in moving from one house to another it is hard to get the cat away. It loves its old haunts more than its old friends.

The cat walks on its toes like the lion and tiger and all its other wild relations. But its claws do not touch the ground. They are drawn up into a sort of sheath and kept sharp for use as a soldier keeps his sword sharp in its scabbard. The paws being covered with fur, its step is silent and its movements are quiet and cautious, as many a mouse has found out.

The Canada Lynx, the House Cat's "Cousin"

We might not care so much for the cat if it were not of use to us in killing those pests of the house, the rat and the mouse. No matter how well fed she is, pussy dearly loves her mouse, and if on the track of one she is not to be turned aside. She[46] will crouch for an hour at a time watching a mouse-hole, never moving a hair until the victim appears; then a single bound and all is over for the little creature. Even if the cat is asleep, no mouse can pass it with safety. Its ears and nose do not seem to sleep.

Once caught, the mouse is played with in a manner that seems cruel to us. The cat makes a game of letting its prey run away, but takes good care it does not reach its hole. This, no doubt, is one of its wild traits, handed down from its ancestors and never tamed out of it. We are told by one observer that a cat will catch and eat twenty mice in a day—this, of course, where mice are plentiful. But when a cat gets a taste for poultry or rabbits it is spoiled as a mouser. And though it is said that cats do not like to get wet, their fondness for fish is greater than their dread of water and they have been known to go fishing in a stream.

It is not easy to make a treaty of peace between the cat and the dog. Do they hate each other or are they jealous of their position in the house? The cat is not a match for the dog and makes haste to get away from the chasing cur, yet when driven into a corner it will put up a good fight for its life, and many a dog has been sent yelping away from its sharp claws. But this state of warfare does not always exist and it is not uncommon for cats and dogs to live together on friendly terms.

Lippincott's Primer

Ready for Business

If we go around the world we shall find cats everywhere and of many kinds. There are not nearly so many varieties of them as there are of dogs and they do not vary much in size like dogs, yet some breeds of cats differ greatly from others. Thus the cats from the Isle of Man—Manx cats they are called—have no tails, while their hind legs are very long and strong and they are covered[48] with a thick coat of fur instead of hair. Let us compare this with the showy Angora cat, with its tail like a great white plume and its long white hair. And they differ as much in character, for the Manx is a hardy animal and the Angora is a delicate parlor cat, its health needing to be carefully looked after.

Then there are the Malay cat, with a tail only half the full length; the royal Siamese cat, fawn colored, with blue eyes and small head; the Carthusian, with long, dark, grayish-blue fur; the South African, with red stripes along its back; the Cyprus, striped and very tall, and the handsome Persian cat with its long silky hair.

As races are apt to be mixed, cat fanciers make color their chief point of value. The principal colors are white, black, blue, blue-gray, smoke-color, orange, and tortoise-shell. A true tortoise-shell tom-cat brings a big price. The color of the eyes is very important. Blue eyes are a sign of deafness. Some white cats have red eyes. As for the hair, cats are divided into two classes, the long-haired and the short-haired, the Persian and Angora being notable for the length of their hair. Most common among our cats is the soot-colored or gray, known as the "tabby," which has black stripes going round its legs, neck, and tail, and also down its sides. These show a return to the wild-cat in color, though tabby is as tame as her rivals.

The cat is not lacking in brain power nor in affection, for in many cases it shows warm love for its mistress. There are various anecdotes of cat logic, of which a few may be told. When crumbs have been thrown out to feed the birds a cat will often hide in the shrubbery, waiting for a chance to spring on them as they feed. One writer speaks of a case where the cat went farther in its logic. The crumbs thrown out had been covered by a light fall of snow, and the cat was seen scratching the snow away. Then she took up the crumbs, laid them on the snow, and hid behind the bushes to wait for the hungry birds.

A cat trick which shows good reasoning power has often been seen, that of opening latched doors, a thing which dogs very rarely do. Thus a cat will spring from the ground, catch the latch handle with one paw and with the other pull down the thumb-piece, at the same time scratching with its hind paws at the door post to open the door. The cat that does this must have seen men pull down the latch for the same purpose and reasoned out that it could do the same.

Also there are cases of cats learning to sound knockers and ring bells, with no one to teach them. Thus a Mr. Belshaw writes: "I was sitting in one of the rooms on my first evening there, and hearing a loud knock at the front door was told not to heed it, as it was only the kitten asking for entrance. Not believing this, I watched for my[50]self, and very soon saw the kitten jump up to the door, hang on by one leg, and put the other forepaw right through the knocker and rap twice." Here the cat is not trying to open the door herself, but to bring some one to open it for her.

Dogs have been known to do the same thing, but not so often as cats, and there is a story of a dog which had seen the cat do this, and after that sought the cat when he wanted to get in, without trying to do the trick himself. One story is told of a cat's ringing a bell by pulling at an exposed wire.

Though the cat's display of thought is not as varied as the dog's, it is very good so far as it goes. Here is a story of a different kind. An oil lamp was being trimmed and some of the oil fell on the cat's back. Afterwards a cinder from the fire fell on it and set it in a blaze. The animal at once sprang for the open door and ran up the street with her back blazing for about a hundred yards. Here was the village watering trough, into which she plunged and put out the fire. The trough had eight or nine inches of water, and puss was in the habit of seeing the fire put out with water every night. In this case it is plain that the animal, as soon as the fire scorched her back, knew very well how to deal with the danger.

After all this, who will say that a cat does not think? Here is another story, told of her cat by a London lady:

"I once had a cat which always sat up to the[51] dinner-table with me, and had his napkin round his neck and his plate and some fish. He used his paw, of course; but he was very particular and behaved with extraordinary decorum. When he had finished his fish I sometimes gave him a piece of mine. One day he was not to be found when the dinner-bell rang, so we began without him. Just as the plates were being put round for the entrÚe puss came rushing upstairs with two mice in his mouth. Before he could be stopped he dropped a mouse on to his own plate and then one on to mine. He divided his dinner with me as I divided mine with him."

The Hungry Babes and Playful Kitten

Such is the cat, a sedate, warmth-loving creature, dearly loving to be petted, yet far less dependent on man or woman than the dog. If left to itself in the woods, the cat knows well how to take care of itself where a dog would often be helpless. As for love of play, we do not find much of it in the cat but we find plenty in the kitten, which is a regular little rogue, lively, playful, frisky, brimful of fun and a cute little creature in all its ways.

Looking around us for our household pets after the dog and the cat, we find that Bunny, the rabbit, comes next. Bunny is a darling pet of the little ones, who dearly love to fondle this pretty bundle of fur. They are sometimes too kind and the poor little thing suffers from their fondness. That is the sad way with children's pets, they are at times loved to death.

But the rabbit is kept for something else than a child's plaything. It is often raised for food, much like the hen and the duck, and its furry skin brings a good price. Thus the Angora rabbit, the most beautiful of them all, has splendid snow-white fur four inches and more in length, which is made into many things useful to wear. Stockings, gloves, shawls, and even stuffs for clothing are made of it. Under-garments made of the Angora fur are said to be very good for gouty persons.

The pretty little Angora is so often kept as a pet by the ladies of France and some other countries that it is called "the ladies' rabbit." It is not always full white, for the Russian Angoras have jet-black noses, ears, legs and tails, which make them look very comical.

You would be surprised if you could see all the kinds of rabbits brought together, for there are many more of them than you would think. A splendid one is the little Silver rabbit, whose skin is used by the fur-makers and brings a big price. Some of them are silver-brown and others silver-yellow in color, but these are not common.

The Dutch rabbit is the smallest of all the bunnies, and when the colors are good it is very pretty. It may be black, yellow, steel-blue, and of other colors, these hues being oddly combined. Other rabbits of small size are the Polish and the French papillon (or butterfly). The one called the Polish is really an English rabbit, and little folks are very fond of it, with its red eyes twinkling out of its snow-white fur. This fur is of high value. The papillon is white, with black, yellow, gray, or blue spots, and is quite pretty.

Then there is the Japan rabbit, also called the tricolor or tortoise-shell. It has black, yellow and whitish markings and rings round its body, while its head is often half yellow and half black.

You can see from what has been said that color has much to do with the difference in rabbits.[54] The ears form another point. They are generally long and stand straight up, giving the rabbit a wide-awake look, but there is a lop-eared rabbit with ears so long and heavy that they hang down on each side and nearly touch the ground.

The king of all the rabbits in size is the Giant rabbit of Flanders. Two others known as giants are the Blue Giant of Vienna and the Blue Giant of Beveren (Flanders). The flesh of these Blue Giants is very good and their fur brings a high price. That of the Blue Giant of Beveren is very thick and close and is of great value. This animal weighs from seven to ten pounds.

We are familiar in this country with the Belgian hare. It is not a hare at all, though it looks like one, but is really a rabbit, and is a fine strong species, weighing six or seven pounds and excellent for the table. It is a little wild, but soon grows gentle with those who care for it. It used to be sent in great numbers to the United States.

You may see from what has been said that there are many varieties of the rabbit. Of those used for food much the best is the Norman rabbit, which weighs nine or ten pounds and is sold in the markets in Paris and other cities of France. The black-and-tan is one of the most beautiful of the rabbits, from its splendid color, but it is very shy and hard to tame. The last we need speak of is the Havana rabbit, of brown or chocolate color, now much raised in Holland.

When the rabbit is taken good care of it is very healthy and those who raise it for the market for its fur find it of much value, since it increases in numbers very rapidly. Many of the young die, it is true, but enough live to keep up a large family.

Rabbits near Their Burrow. The Young at Play, the Mother Alert for Danger

A good rabbit home may be made of a number of boxes of about the same size, raised four or five inches above the ground and facing the sun if they are kept in the open air. Casks or barrels may also be used, with a door at one end of the barrel, covered with netting to keep out rats and mice.

It is amusing to see the care with which the mother rabbit makes her nest when she is about to have young. Some soft straw and hay is put in the box or cask and this she carries into one corner of her home, makes a hollow in it, and lines this with fur pulled from her breast, to make a warm, soft nest for the little brood. When the young are born she must be given something juicy, such as a turnip or carrot, or perhaps a little warm milk or water, for if left thirsty she grows feverish and is apt to eat the little ones, not knowing what she is doing. She cannot bear thirst and it makes her do strange things. There may be new broods of young five or six times a year, and if only three or four of each brood live there will be a good many by the year's end.

There are many other animals which are at times kept as pets by man, though the dog, cat, and rabbit are the most common. The Ferret is often kept, though not as a pet. It is a half wild little brute, hard to tame and used for hunting, for some kinds of which it is very useful. It is a sort of white weasel, long and slender, so that it can make its way through rat holes or rabbit burrows. A brave little thing, it is not afraid to attack the largest rat, and is good at clearing a house of rats and mice. It is also used to drive rabbits from their burrows. Nets are set to catch the prey or they are shot as they rush out. But a muzzle is put on the ferret, for if it can kill the[57] rabbit and drink its blood it may stay for days in the hole. At other times a long string is tied to it, so that it can be pulled out. The ferret is sometimes used to chase and catch fowls. Once caught, a single sharp bite on the neck puts an end to the life of the fowl.

The Otter, One of Nature's Fishers

The ferret is a blood-sucker, and this makes it dangerous when it has once tasted blood. It has been known to attack a child in its cradle when the mother was away, and will bite its master if not given enough food or ill-treated in any way. It is an ugly tempered little brute, usually unfit for petting. But Mr. Romanes tells of one kept by him that was fond of being petted and would follow him like a dog when he walked out. It was also taught tricks, such as begging for food and leaping over sticks, and those it never seemed to forget.

The Guinea-pig, which is often kept as a home animal, has none of the fierce ways of the ferret. In spite of its name, it has nothing to do with the real pig, but is one of the gnawing animals, a timid and stupid creature, that first came from South America. Large numbers of them are found on the banks of the La Plata River, being there known as the Cavy. They burrow in the ground and feed on fruits and herbs.

A Guinea-Pig. Pig Only by Name, not by Nature

What people like in the Guinea-pig is its pretty coloring. The wild form is of a grayish-brown color, but as kept on the farm its color is white, with patches of red and black. It is of no use to man except as a pet, for it is not fit for food and is too stupid for anything else. It has been said to drive off rats and mice, but this is a false notion.

What can we say of the Hedgehog as a pet? Not much, though it is often kept. It is no more a hog than the Cavy is a pig, but is not one of[59] the gnawing animals, for it lives chiefly on mice, game, birds, frogs, insects and worms. This makes it very useful in a garden or in a house in which roaches are a pest. The odd thing about the hedgehog is its armor of sharp spines. When attacked by a dog or other animal it at once rolls itself up into a ball with the spines pointing out in all directions like those of the porcupine. Thus the little creature is quite able to take care of itself. The dog may roll it about with his foot but is afraid to bite into its spines.

The Weasel has also been tamed and been found a lovable little animal. The Otter is another tamable creature and can be taught to catch fish and bring them to its master. Dr. Goldsmith tells us of one that would go to the fish pond when told to do so, drive the fish into a corner, seize the largest and carry it in its mouth to its master.

There are many other animals that have at times been kept as pets, among them such a queer one as the Kangaroo, with its very long hind legs and very short fore-legs and its habit of jumping instead of walking. A pet kangaroo of which we are told was a very man-like or monkey-like creature in its way of eating, using its fore-paws like hands to take food from its dish. What it most enjoyed was a rabbit-bone, which it would take in its right paw and pick clean, eating it with great relish.

It was very fond of tea, but liked to have it[60] well sweetened. If the milk was left out it would lash its tail, draw up its tall figure angrily and bound away with a long leap. Kanny had a very sweet tooth and liked sugared almonds best of all titbits.

Other odd pets we have heard of were a couple of Prairie dogs, brought from Texas to Scotland and kept in a village garden. They proved very friendly but needed to be locked up in a strong box at night, for they would gnaw into shreds the mats and rugs and everything open to their sharp teeth. But they were loving little things and had a way of showing affection by a gentle pressure of their teeth on the hands of their friends. If a stranger touched them in a timid way he was apt to get a pinch but if a firm hold was taken they seemed to like it.

These are only a few of the animals that have been kept as pets. Cardinal Wolsey made a friend of an old carp, Cowper, the poet, loved to play with his hares, and Lord Clive, the soldier, kept a pet tortoise. Others of less note have made pets of snakes, frogs, lizards, and various other animals. We have not tried to name them all and have said nothing about so common a pet as the monkey, for we must keep this funny fellow for a chapter of his own.

Is there anywhere, has there ever been, a finer or more useful animal than the horse, the swift racer of the plains, the noble lord of the desert, the mainstay of the city and farm? To us the horse is as familiar a friend as the dog. We see this fine animal everywhere that man lives, now valued for his speed, when he flies away over the racing field "with the wings of the wind;" now admired for his beauty and stately form, when he draws the coaches of kings and nobles; now for his great size, as the huge draught animal; now for his small size, as the dainty little pony. It is sad to say also that we often see him as the old, worn-out drudge of the streets, hard-worked, half-fed, and slowly dying in harness.

Go back as far as we can in history it is the same story still. The horse is man's friend and helper, carrying him in the battle-field, working for him on the farm, bearing him in his travels. But if we go back beyond history we come to a time when the horse was free and wild. It was not yet tamed by man, but was hunted and killed for[62] food. In the caves that were the homes of early man great numbers of horses' bones are found, left from the feasts of old-time savage men.

Friends and Comrades

The wild horse has not gone from the earth. Troops of them still live on the vast plains of northern Asia, and they are found also in the forests of the south of Russia, small, wiry animals, full of life and spirit. These are called Tarpans. Centuries ago wild horses were to be found in Spain and parts of Germany, but these have all been caught and made to work for their living. America has its wild horses also, plenty of them in South America, but they are not natives of the soil. Some of the horses brought over from Spain by the early settlers escaped from their masters and became free and wild in the great grassy plains.[63] These are known as "mustangs" or "cimmarones," and no use is made of them except by the Indians, who kill and eat some of them and tame others.

No matter where we find horses they are very much the same. They are not like dogs, of which there are so many kinds. Of course there is much difference in the size of horses and also in their colors, but little difference in other ways. If we travel together over the earth and see the horses of the various countries we shall find them very much alike. Yet such a journey is well worth taking, for it will show us many things we ought to know.

The horse family, as very likely you know, differs from all other animals in having only one toe. It comes from animals that had a number of toes, but these have all gone but one, and the nail of this toe has grown into a thick, horny hoof which keeps the foot from being hurt as the horse gallops over its native plains. Its home is on broad, grassy levels, soft to the tread. But when used by man it has to travel much on hard and stony roads which would soon wear out its hoof. So to save this it has to be shod with iron. The hoof is so thick that the iron shoe can be nailed to it without touching the flesh.

There are a number of animals much like the horse, but unlike it in several ways. These animals[64] we shall speak of further on. One of the special points by which one knows the horse is the long hairs which cover the whole length of its tail. Another is its splendid, flowing mane. It has also longer legs and smaller head and ears than the other members of its family. Altogether a fine horse is one of the handsomest of all animals. And among them all it is one of the most useful to man.

Rosa Bonheur's Famous Picture of the Horse Fair

Now let us start on the journey abroad we laid out and see some of the world's horses. If we go first to the grand plains of northern Asia, the broad, level country called the steppes, the people of which are always travelling about with their flocks and herds, we shall find ourselves in the native land of the horse. In far-off times this was the great region of the wild horse and here very likely it was first made a slave of man.

All the time on the move, as these shepherd people were, driving their cattle and sheep from[65] pasture to pasture, the horse was fitted for their use by its strength and speed, and very long ago it must have been caught and made to bear the saddle and bridle and carry man on its back. No one can say how long ago this was, but these people are now the great horsemen of the earth. They live with their horses, sleep with them, and love them even more than they do their children.

The Mongols of the steppes have almost lost the art of walking. They live so much on horseback that their legs have become curved instead of straight and when they walk their bodies bend forward as if they were riding. The time was when great hordes of these wild horsemen swept over the south of Asia and a great part of Europe, capturing and killing the people wherever they came. Thus the horse has been of great use in war.

The horses of the steppes are of middle size but are very strong and can go long without food and bear very hard work. They have quick, alert ears and eyes full of life and spirit, and can easily travel from forty to sixty miles in a day. Their color is light bay, cream color, white spotted with red, or sorrel, and some of them are quite pretty.

Here let us step aside to the British island and tell the story of a famous horse, Black Bess, belonging to a famous rider, Dick Turpin, the highwayman. Once when Dick was chased by the soldiers, this noble animal carried him from London to York, a distance of one hundred and[66] five miles, in eleven hours. And this was done over rough roads and without a stop to eat or drink. As she entered the gates of York the splendid beast fell dead. You may learn from this what the horse is able to do.

If we wish to see the noblest and finest of all horses we must go from the grassy steppes of the north to the sandy deserts of Arabia, where for thousands of years has been kept the splendid Arab breed, the pride of their masters and the swiftest and most beautiful of the horse tribe. Many of these have been brought to Europe to give their blood to the racing stock. Black Bess, Dick Turpin's noble horse, had much Arabian blood. But the best of these horses are not sold out of their native land, for a true Arab horseman would almost rather sell his soul than his horse.

Persia also has its noble breed of horses, kept for desert travel and of the same type as those of Arabia. The mountain horses of the Balkans are of a similar type, beautiful in color, often a golden brown, with dark brown manes and tails, and soft, glossy coats. Like the Persian and Arabian they have delicate but strong bones, large muscles and much power of work and travel.

Russia, with its vast plains, is the great country for the horse. Most of these are the horses of the steppes, which we have spoken of, but the Russian peasants have many millions of working horses, tall, stout, strong beasts, with powerful legs and[67] solid hoofs. They are not only strong, but willing and ready, and are good for riding as well as drawing.

Germany comes next to Russia in the old world in numbers of horses, and is noted for its fine, large, handsome carriage horses. From the days of George I. of England, to Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee in 1897, eight of the splendid horses of Hanover were used to draw the royal coach on all state occasions, and fine, stately animals they were.

France has several fine breeds of horses, from the heavy Norman Coach horse to the powerful French Draft horse and the well-known Percherons, much used in this country. In England the hunting and racing horses stand first. These, known as Thoroughbreds, are in great part of the Arabian stock and there are no finer animals to be found for the race-track. Of the many other large breeds in Europe we shall speak only of the great draft horses of Belgium, known the world over for their fine shape, great muscles and vast strength.

Coming down now from these elephant-like horses it is a long step to the pony, the toy animal found in the cold countries of the north. Best known among these are the Shetland ponies, from the frosty islands north of Scotland. These tiny creatures, sometimes less than three feet high, are ridden by children and used in circuses. But[68] the chief use in their native land for these poor little ponies is in the coal mines, to draw the coal carts. Once taken into a mine, they never see the light of day again, some of them living fifteen years in these dark prisons.

From Davis' Practical Farming

Pure Bred Clydesdale Draft Horse

Another small, pony is the Norker horse of Norway, a strong little creature, noted for its power of mountain travel and of swimming. The ponies of Iceland are much like these, with thick coats of hair. These get their food in winter by scraping away the snow with their hoofs and eating the thin coat of grass and moss below.

Sweden also has its ponies, as also the mountain regions of Britain and other northern countries; but ponies are not confined to cold regions, for we find them as far south as Italy and Greece, and in the Grecian islands known as the Cyclades is a breed of ponies said to be still smaller than those of the Shetlands.

If we now cross the sea and come to our own country, the United States, we find no native breed of horses, all those we have being of European stock. This may seem strange when it is known that America was one of the native homes of the horse. The ancestors of the horse dwelt here, from little, five-toed animals of the size of a fox to the large one-toed animal of the recent age. All over America horses once spread, from the Arctic Seas to Patagonia, but when white men first reached this soil not a horse remained. They all had gone, no one knows how, and the continent had to be supplied again from European stock.

The horse has long been used in many ways by man; in cart, wagon, and plough; on the race-track and in the hunting field; in war and in peace. It has been man's great aid and helper, and through all the ages until less than a century ago it was the fastest means of travel or of sending news. Up to about 1830 all land travel was on horseback or by coach, or else on foot. Then the[70] locomotive came and brought a great change. It was later still when men began to send news by lightning express over the telegraph wire. In early days in our country the mails, which now go so fast, were carried by old men on horseback, who spent the time in knitting stockings as they jogged along slowly over the rough roads.

A Roman Chariot Race

The horse has long been used not only in travel but also in sport, as a hunter and racer. When we read the story of ancient days and of the old Greeks and Romans we find many tales of chariot races. These old nations had great oval buildings, with thousands of seats, and a long oval race-track around which the horses had to run several times to finish the race.

These were not horseback races, like those of to-day, but races with chariots like those used in[71] war. Each chariot was drawn by four swift horses and driven by a man who stood upright with reins and whip in hand and drove his horses at full speed round the track. The great and rich people took part in these races and many thousands of lookers on cheered them wildly as they sped onward like flying eagles. If any of you should like to read a good story of an ancient chariot race you can find one of the best in General Lew Wallace's novel of "Ben Hur."

In the Middle Ages riding was done on horseback, and when carriages and coaches were brought into use people despised those who rode in them, calling them weak and lazy. So in those days the racing was on horseback, as it still is in most cases. Many of these races went on in the open country, through rough fields and over streams. They were called "clock races," for the prizes were little wooden clocks, or clock towers. These were afterwards made in silver, and from them came the name of "steeplechase," by which such races are now called.

Regular race-courses began in England in the reign of James I., after 1600, and in later years many Arabian horses were brought to that country and racing became a common sport. One of the most celebrated of those early racers was Eclipse, a horse never beaten and never needing whip or spur. Since then there have been many famous racers, and racing has become very popu[72]lar in all parts of Europe. A bad feature of it is the habit of betting on the speed of horses, by which many men have lost all their money.

Thoroughbred Racing Horse. A Trained Horse of This Breed is the swiftest of all Animals