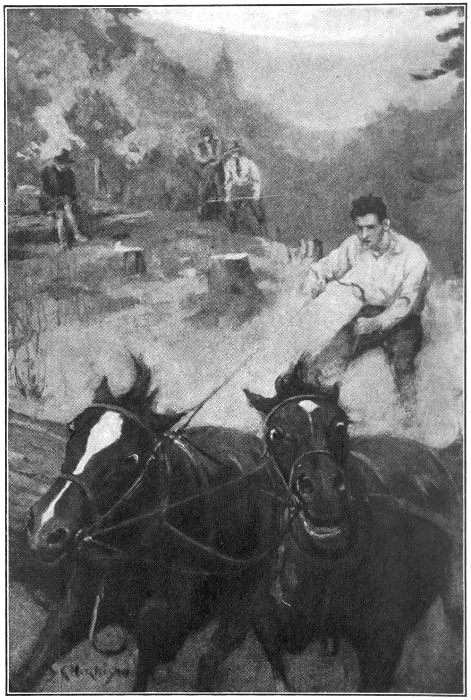

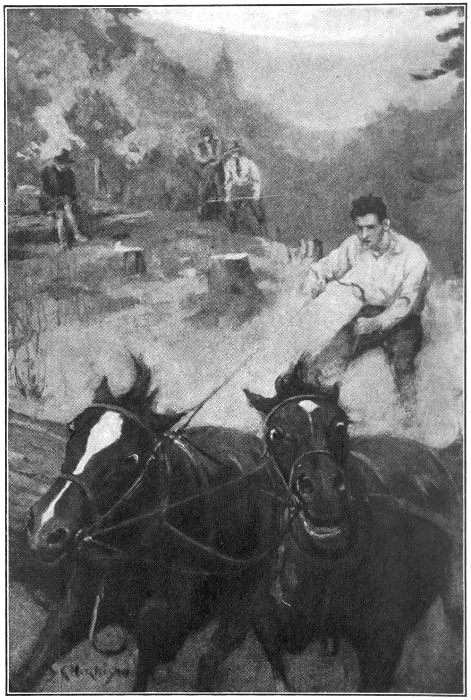

JIMMY TRIED DESPERATELY TO STAY HIS TEAM.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Scott Burton in the Blue Ridge

Author: Edward G. (Edward Gheen) Cheyney

Release Date: April 23, 2020 [eBook #61908]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SCOTT BURTON IN THE BLUE RIDGE***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/scottburtoninblu00chey |

JIMMY TRIED DESPERATELY TO STAY HIS TEAM.

SCOTT BURTON, FORESTER,

SCOTT BURTON, LOGGER,ETC.

The ticking of the old grandfather clock in the neat little New England house was the only sound to break the stillness. So still it was that any one approaching the house could have heard the clock distinctly and would certainly have overlooked the silent figure in the old rocking-chair. But a man was sitting there, nevertheless, completely absorbed in his own thoughts.

An old gentleman appeared in the doorway and stood there for an instant before he saw him. Then his face lighted up.

Hello, Scott! I thought you had gone out and I wanted to talk to you

about your new assignment. Mother tells me that you have your sailing

orders now.

The son looked at him with a smile, but his face still wore a puzzled frown.

Yes,

he said, I have my sailing orders, but—

Good or bad?

his father interrupted anxiously. You don’t look

overjoyed with them.

The old man was really worried.

I don’t know just what to think of them,

Scott frowned once more and

opened the letter for the hundredth time. They have assigned me to a

timber sales job in the North Carolina mountains.

Well, that sounds good enough. They say that is a beautiful country and

it is a place I have always wanted to see.

Oh, the country is all right,

Scott said brightening, and I am crazy

to go there, only I had my mind set on going back to my old place in the

southwest.

And again he frowned. It is not the country but the job

that I am afraid of. Sometimes I am almost sorry that I caught those

range thieves out there in Arizona.

Why, Scottie boy! If it had not been for that you would never be where

you are in the Service to-day,

his father remonstrated proudly.

Oh, I know that it made me solid with the Forest Service and gave me a

chance at a supervisor’s job years before I would ordinarily have had

one, but they have been using me as a sort of detective ever since. I

was lucky enough to catch those timber thieves in Florida, but I am no

sleuth and I’ll fall down on that job sooner or later.

But, Scott, I don’t believe this is detective work. I expect they have

heard what a tremendous success you made of your own logging job last

winter and want you to look after the logging work down there.

Yes,

Scott admitted, I think you are partly right. But why transfer

me down there when there are local men who understand those methods?

Logging in New Hampshire and logging in North Carolina are very

different propositions.

Maybe the local men cannot handle it and they know you can,

his father

suggested proudly.

Of course that’s what you think, dad,

Scott said affectionately, and

it may be what they think, but I am afraid that there is something else

wrong.

This rather gloomy conversation was broken up by Mrs. Burton, who had

come to the doorway unnoticed. Well, well, why worry over something you

don’t either of you know anything about? Maybe we do not know what you

are going to do in North Carolina, but we do know that you have to leave

us in the morning and we don’t want to waste what time we have left

worrying. Come on in to supper.

Scott laughed. All right, mother, you always say the sensible thing.

I’ll bet there is nothing wrong with the supper no matter what may be

the matter with the new job.

So they went in to supper cheerfully enough and all three spent the evening poring very busily over the atlas, and trying to see what they could find out about the new country. Caspar, the little town where the headquarters were located, was not shown on the old map, but they found out a great deal about the country in general, and it was bedtime before they knew it.

There,

Mrs. Burton exclaimed cheerfully as they said good night, I am

satisfied. I’d be willing to go to that country on any old kind of a

job.

Scott was not ordinarily given to worrying much and by the time his train pulled out of the quiet little Massachusetts village the next morning he was looking forward eagerly to seeing this new country and had forgotten all the imaginary troubles which the new work might bring.

His orders were to report direct to Caspar, but he had half a day between trains in Washington and took the opportunity to visit the Forest Service offices. He met a few friends and became personally acquainted with a number of men who had before that been to him only a name attached to the end of an official letter, but he learned nothing definite in regard to his new work. The chief of the particular branch in which Scott was employed was out of the office and the inspector who was to meet him in Caspar had already gone to North Carolina. That looked as though there must be something unusual there, but Scott resolutely refused to worry about it any more and settled down in the car seat to enjoy the scenery of Virginia, which was altogether new to him.

The little shanties scattered all through the country and the grinning black faces which crowded one end of the platform at every station reminded him of Florida, but the country itself was very different. Instead of the flat sand-plains covered with dense stands of yellow pine the train wound through rolling clay hills and hardwood forests until it lost itself in the foothills of the mountains just as the sun went down. Scott peered eagerly out of the car window until he could no longer see even the telegraph poles beside the track.

Morning found him at a junction point in the heart of the mountains. These mountains were not like the Rocky Mountains as he had known them in the southwest. There was none of that stark grandeur of the bare rocky slopes and flat-top mesas, but there was a peaceful beauty about them which reminded him more of the overgrown Massachusetts hills; soft green slopes towering above the valley to a surprising height, considering the low absolute altitude of the range. There was as much difference between the valley and the mountain peak as there usually was in the Rockies, but Scott remembered that the valleys in the Rockies were as high as many of these peaks.

A little branch line carried him down a narrow valley between what appeared to be flat-topped, unbroken ridges clothed in every kind of hardwood tree that Scott had ever heard of, and capped with a rim of dark green spruce which fitted over it like a black cape. Here and there a peak rose conspicuously above the level ridge.

It must be great in those forests,

Scott thought, and the views from

those peaks ought to be worth seeing. I tell you there has got to be a

lot of trouble in this job if I can’t enjoy myself in this country.

He was trying to catch a glimpse of a particularly high peak which

showed itself every now and then above the dark spruce ridge when the

conductor called, Caspar,

and Scott had to hurry to get his pack sack

and suit case off the train at his headquarters.

When the dinky little train pulled out and left Scott standing on the platform, he realized why he had not seen the town of Caspar from the car window. It consisted of a railroad station, two stores, four dwelling houses and another large, decrepit-looking building which could not easily be classified, and they were all on the other side of the railroad track from Scott’s position in the car. From that side of the train no one would have suspected the presence of a town anywhere in that vicinity. The mountain slope came down almost to the railroad track and the forest on that side was almost unbroken.

The station agent seemed quite interested at the sight of a stranger. He watched Scott for a minute and seemed to be studying him in his own slow way. Finally he seemed to decide that it would be safe to speak.

Howdy! Stranger in these parts, be ye?

he drawled.

Yes,

Scott said, is there a hotel here or any place where a man can

stay?

Reckon you can stay at the hotel. Ain’t no place else you could stay in

this town and live.

Scott thought at the time that that was a rather peculiar remark for any one to make, but when he found that the station agent also ran the hotel he charged it up to professional pride. When he saw the hotel he wondered how any one could have any professional pride in it.

The hotel turned out to be the nondescript building which stood, or rather sat, apart from the others at the end of the street. It was a large, rambling, barn-like structure a story and a half high. Half a dozen gables stuck up from the side of the roof. It looked very old and its first coat of paint had never been renewed. The ground around it was as bare as the weathered clapboarding. There was no sign of any attempt at beautifying either grounds or building. A rough picket fence separated it from the rest of the village, but just why no one could tell, for the ground inside the fence was, if anything, more barren than that outside. Altogether it was a forlorn-looking place.

The proprietor led Scott upstairs into a room large enough for a banquet hall. It looked even more desolate, if possible, than the outside of the house. It contained a bed covered with an old patch-work quilt and two boxes—one to serve as a chair and the other as a washstand (you could tell which was the washstand by the old tin basin half full of dirty water).

Scott looked around the room in dismay, but he had made up his mind that he would have to put up with it when he caught a sickening odor, as of a dead mouse, that apparently came from the closet. That he could not stand. He had heard of the touchiness of these people, and he did not want to offend them, especially as he would probably have to make the place his headquarters for some time. But he had to get out of there by some means.

You haven’t any bedroom on the first floor, have you?

he asked, trying

to conceal the disgust he actually felt. I may be here a long time, and

there may be a great many people coming to see me, and a ground-floor

room would be much more convenient.

Shore, I reckon we can accommodate you,

the man said, and he led the

way apathetically downstairs again.

He opened a door off the long back porch and stepped back to let Scott enter. It was a palace compared with the upstairs room. The furniture was old, but everything was there down to a rag carpet on the floor, and, moreover, everything looked clean.

This will be fine,

Scott said as he glanced quickly about. What time

do you have dinner?

Twelve o’clock, most times, but there ain’t anything certain about it.

He paused at the door on his way out. It ain’t none of my business, but

you ain’t a U. S. marshal, be you?

No,

Scott laughed, nothing like that. Why, are there many moonshiners

around here?

I ain’t saying anything about moonshiners,

the man replied in the same

dull tone. I was just going to tell you that this was a mighty

unhealthy country around here for the U. S. marshal.

Scott did not know whether this was meant as a friendly warning or as a threat, and before he could ask anything more about it the man was gone. As he was not in any way connected with the United States marshal, he thought no more about it.

Left to himself, he began to examine the room more closely. It was clean all right, but the general effect of it was most grotesque. The high, carved head-board of the old walnut bed might have had a place in a medieval museum, but here in this room it looked out of place like everything else in it. When Scott’s eyes fell on the wall paper, he stood aghast. He counted thirty-seven different patterns, each a small square evidently taken from a country storekeeper’s sample book, and only a third of the wall was covered. The east window was heavily curtained with portières, lace curtains and a shade. Scott peeped out. It opened almost into the mountainside and no human habitation was in sight. The glass door opening on to the back porch—which was by far the most frequented part of the house—was not curtained at all. It was a queer place, but Scott had been in worse, and he decided that it would have to do.

He had been so interested in finding a place to stay that he had forgotten all about the man from the Washington office who was to meet him here. He went out to inquire for him. The dining room opened on to the porch next to his room and the kitchen was next to that.

The man was nowhere to be seen, but there were three women in the kitchen and they were feverishly discussing Scott’s probable business. Complete silence fell on them all when he appeared in the doorway.

Pardon me,

he said. Do you know whether Mr. Reynolds of the Forest

Service has been here?

The women looked at each other as though an important problem had been solved before any one answered.

Then one of the women answered with a question: Are you Mr. Burton?

Yes,

Scott said.

Mr. Reynolds left here this morning. He said that if Mr. Burton, the

new supervisor, came to tell him he would be back to-night or to-morrow

morning. I was looking for a much older man,

she added looking at him

curiously.

Well,

Scott laughed, time will correct that.

Scott noticed that these women were all sizing him up just as the station agent had done a little while before. He went back to his room, and looked in the glass to see what could be wrong. He could see nothing to attract attention. He tried to forget the occurrence and went out to see the town and surrounding country.

He wandered down the street, if the road between the two stores could be called a street, and wondered why there should be two stores in such a place. Judging from the unbroken forests on the mountain slopes he did not see where enough people could possibly come from to support any store at all.

On the porch of each store there was a small group of idlers holding down the dry-goods boxes, and Scott saw that they were sizing him up just as the women had done. Moreover, the stare of these men seemed to be distinctly unfriendly. It made him feel uneasy. He was glad when he had run the gauntlet of unfriendly stares, and was out in the open road with only the railroad station and the mountains before him. But he had one more examination to stand. The station agent was watching him from the corner of the platform. In fact, Scott caught him squatting down to get a better view of him even before he came out in the open. He resented this officious spying on his movements and turned aside into a mountain road which wound its way up a timber-covered slope.

Heh!

Scott turned to see the man coming towards him at what was an

unusual gait for him. Didn’t buy anything at the store, did you?

Scott looked at him indignantly for an instant, but he remembered again

that he had to live with these people, probably for a long time, and did

not want to offend them. No,

he replied as pleasantly as he could.

Why?

I just wanted to know,

the man replied frankly. But if you haven’t

done it, don’t.

The man had evidently noticed that Scott had resented

his interference and he walked away with considerable dignity without

making any further explanation.

Scott started to call him back but changed his mind and continued his walk up the road. He wanted to get away from these inquisitive people for a while, and try to think things over. Fate, however, seemed to have decided otherwise. He had gone a little more than a quarter of a mile up the winding road through the heavy hardwood timber when he came to a little cabin set back only a few feet from the road behind the inevitable picket fence. An old man was sitting on the porch, and he sized Scott up with the same all-consuming curiosity, but his gaze seemed to be wholly friendly. There was none of that furtive animosity he had felt rather than seen in the groups down at the store.

Howdy, stranger?

the old man greeted him pleasantly. Be you the new

supervisor?

The old man’s manner was so evidently friendly, and his curiosity so frank that Scott warmed up to him at once.

Yes,

he admitted cheerfully, I’m the new supervisor.

Haven’t bought anything at the store yet, have you?

the old man

continued in his friendly way.

There was that same question about the store and Scott stiffened for an instant, but he thought better of it. Maybe he could learn something from this old man.

No,

Scott said, I have not bought anything from the store. Tell me,

why does everybody ask me that? I have not been in this town much more

than half an hour and two people have already asked me if I have bought

anything at the store. What is the meaning of it?

The old man looked at him thoughtfully for a minute as though hesitating to answer the question. Then he answered slowly as though pronouncing final judgment:

Because when you do buy anything from one of those stores, you might as

well leave the town for all the good you’ll ever be able to do in this

country,

and he turned as though to enter the house.

The old man’s statement seemed so ridiculous that Scott hesitated to believe it. He thought that the man must be making fun of him, but he recalled the station agent’s warning. There must be something in it. The whole community could not be conspiring just to play a joke on him. Before the old man reached the door he called him back.

Just a minute, please. You are the second man to warn me not to buy

anything at that store. Why shouldn’t I? What has buying at the store

got to do with running a national forest? I can’t see the connection.

The old man looked at him and smiled sarcastically. Neither could the

other two men who came here before you, and they both had to leave.

Scott’s curiosity was now thoroughly aroused, and he determined to pump

an explanation out of this man. He smiled winningly. Then tell me the

secret so that I shall not have to follow them.

At his change of tone the old man’s sarcasm disappeared immediately.

Well, if that’s the way you look at it,

he said with all his old

friendliness, why, maybe I’ll try to tell you. You couldn’t tell those

other fellows anything.

I would certainly appreciate it,

Scott said, as he settled himself

down on the fence to listen. I have come here to run this forest, and

if that store down there has anything to do with it, I want to know

about it.

Come in, come in,

the old man repeated hospitably. It’s a long story,

and you might as well sit down to listen to it.

Scott gladly stepped inside the fence, and took a seat opposite his host

on the porch. By the way,

he said, I thought I saw two stores down

there in the village. Which one do you mean?

That’s just the point. If there was only one store there you could buy

all you pleased, but if you buy anything from one of those stores now,

the fellow who owns the other one would sure get you.

But can’t a man buy where he pleases in this country?

Scott asked

indignantly. His spirit rebelled at any one dictating to him the way he

should run what he considered to be his own business.

Not and live in peace,

the old man answered sadly. I’ll tell you the

story, and then you can do as you please.

You see the people here in the mountains don’t move around much. When a

man gets used to these mountains he never wants to live anywhere else.

The children don’t marry, and go off somewhere else to live; they just

put up another shanty, and live close to home. The families stick close

together, and form a kind of settlement. Most everybody in the

settlement is kin to somebody else.

The Morgans live in the settlement up on this side of the valley, and

the Waits over there on the other side. They were good friends and

getting along fine till the railroad come down the valley. They called

old Zeb Morgan and old Foster Wait together to decide where the station

ought to be. They got into a row over it somehow, and before anybody

could interfere Foster had pulled a gun and shot Zeb through the heart.

That was forty years ago. Well, it was a murder all right, and no excuse

for it except Foster’s notorious temper. The sheriff took Foster off to

jail, and that ought to have ended it. Would have ended it, too, if it

had not been for Zeb’s half-witted brother Jim. Everybody knew Jim

wasn’t exactly right in his head, but he worshiped Zeb, and when Zeb was

shot he went plumb crazy, disappeared and nobody saw or heard of him for

a week. Next thing anybody knew Jim had turned up in the middle of the

Wait settlement and shot two of Foster’s brothers.

Well, they should not have held the Morgans responsible for the actions

of a crazy man, but they did, and the fight was on. The dead line was

drawn down the middle of the village street, and every time a Wait

stepped over that dead line, he had to duck Morgan lead, and the Waits

were just as quick on the trigger on the other side. Every once in a

while some one on one side or the other would get drunk and shoot across

the line.

It got pretty bad. All the kin folks got mixed up in it, and there was

a funeral every two or three months. There has not been much shooting

for the past five years. The Morgans got the worst of the scrap in the

early days, and there’s only old Jarred and his two sons left of the

direct descendants of Zeb. Unless you count his little granddaughter

Vic. She’s the fightenest little wildcat in the whole bunch. Of course

there are lots of relatives, but they had cooled off pretty much till

this national forest business came along to stir them up again.

But I most forgot the store. You see old Tom Wait had a store in the

village before the trouble began, and it was all that was needed, maybe

a little more, but of course after the trouble no Morgan would deal

there. Been shot if he’d tried it. So Jarred’s boys had to start a store

on the other side. That’s where the two stores come from. Buy anything

from one of them, and you have all the other side of the mountain down

on you. Now maybe you can see why I warned you.

Scott sat in silence for a moment while the old man watched him curiously. He was dazed by what seemed to him an impossible situation. How could such a horrible state of affairs exist in the heart of a civilized country?

Isn’t there any way of bringing the two families together and stopping

this senseless fight?

Scott asked earnestly. Surely they must see how

it is hurting them both. Has any one ever tried to stop it?

The old man shook his head sadly. The Morgan boys might quit if they

could find any way to do it. They know it is only a question of time

till they will be killed. Three Morgans can’t hold out forever against a

dozen Waits, and that is what it means because their kin folk are not

going to stick by them much longer.

It would not be possible to persuade this man Jarred to give up the

feud?

Scott asked.

The old man smiled sadly. It’s clear you ain’t seen him, stranger. Old

Jarred would give away anything he’s got except his pride, but it takes

only one look at him to see that he’d never give up to an enemy.

Scott sat for some minutes pondering this extraordinary situation, and the old man continued to watch him rather wistfully. Would he try to make peace between these warring factions, or would he ignore them, and be run out of the country as the other two had been?

When Scott looked up he smiled at the old man gratefully. I don’t know

what I can do to stop this thing. It is pitiful to think of that old man

eaten up by his hatred, and holding out in his pride against the world.

Maybe I cannot do anything to stop it, but I certainly do not want to do

anything to stir it up. I can’t tell you how much I appreciate what you

have told me. To whom am I indebted for this information and advice?

My name is Sanders.

Old man

Sanders they call me.

And I take it that you are not mixed up in this feud on either side.

Who else is not in it?

The station agent. He has to be neutral.

And how did you happen to keep out of it?

Scott asked.

Because I am a Quaker,

the old man answered proudly, and do not

believe in fighting. And now,

he added with the same sad smile Scott

had noticed several times before, one of my daughters has married a

Wait and the other a Morgan.

Scott rose to go. Well, Mr. Sanders,

he said earnestly, I have almost

as good a reason as you have for keeping neutral. I am certainly obliged

to you for your advice, and I may need your help again. In the meanwhile

I shall keep away from those stores, and try not to stir anything up.

Scott walked slowly on up the mountain road with bent head, and when the old man had watched him out of sight he continued to gaze dreamily at the turn of the road where the young man had disappeared.

He’s not a fool like the others, anyway,

he said aloud, and I think

he’ll stay here.

Scott wandered on. He wanted to find a place where he could be alone and think.

Two miles farther up that same road a little log cabin stood back from the road about fifty feet behind its weather-beaten picket fence. The little yard, like most of the yards in that section of the country, was perfectly bare, and at first glance it seemed to be deserted. But if a member of the Wait settlement had tried to enter the yard, he would instantly have been aware of a very real presence.

Seated on the doorstep of the cabin, and so motionless that he might have been a part of it, was a man clad in a black sateen shirt and homespun trousers tucked into heavy Congress boots. Judging from the silvery whiteness of his hair he might have been eighty-five, but from the strong, stern lines of his thin, smooth-shaven face he might have been forty-five. There was no sign of nervousness. Not a finger moved and his eyes rested unwaveringly on a small clearing half a mile down the mountain where he could catch a glimpse of the road to the village.

A white flag waved for an instant in the clearing and the lines of his face relaxed. The sternness had given way to an expression of anticipation. The man’s eyes shifted from the clearing to the bend in the road just below the cabin. Other than that there was no movement. It would have taken a careful student to have discovered that an all-consuming curiosity was gnawing at this man’s heart. He seemed to be without a care in the world. Certainly no one could have guessed that he was suffering from a suspense which was almost unbearable.

Suddenly a slip of a girl, not more than thirteen years old, and small for her age, came running around the bend in the road. The brown of her sunburned legs twinkled in the patches of sunlight that came through the trees, and her blue-checked calico dress fluttered in the wind as she ran with unfaltering stride. It was not an impatient burst of speed at the end of a journey. She had been running steadily all the way from the village, almost two and a half miles away and nearly a thousand feet below.

At the sight of her the man arose and stretched his gaunt form to its full height. The coming of the child meant much to him, but he showed no sign of curiosity. She stopped before him with chest heaving and dark eyes aflame.

He went to Wait’s,

she panted.

The lines in the old man’s face tightened, and he seemed to grow taller, but he made no answer.

That was the man who came yesterday,

she continued furiously. He

bought a sack of tobacco at Wait’s this morning, and went up on the

other mountain. The other one who came this morning didn’t go in

nowhere. He ain’t much more than a boy.

Where is he?

the man asked sternly. At the hotel?

No, he went there, but he only stayed a few minutes. Then he walked

right through the village and started up this way. I passed him just out

on the road.

Did he see you?

No,

she answered contemptuously. I was in the brush, but he would not

have seen me if I had run right by him. He was looking at the ground and

frowning.

The man turned the news slowly over in his mind before he answered.

So the new supervisor is a young lad, is he?

She nodded.

And he did not go in anywhere,

the man continued meditatively. What

sort of looking man is he?

He’s two inches shorter than you are, grandpa, but he is heavy and

strong,

she said confidently, with the air of one who is accustomed to

gauge the physical builds of men. He’s wearing one of them uniforms,

and he’s dark and good looking.

He gave the girl a quick, searching glance. Well, don’t make friends

with him yet, Vic. He has not gone into Wait’s, but he has not been in

our store either. Let’s wait till we see what he is going to do.

Me make friends with one of those government men,

she burst out

contemptuously. They all of them side with the Waits. I’d spit in his

face if he spoke to me.

Her grandfather smiled approvingly. Oh, I would not do that, Vic, not

till he gives you some reason to. This one may turn out to be all

right.

Then let him keep away from the Waits, if I have to be polite to him,

she snapped.

The old man took the girl tenderly by the shoulders, and looked at her

earnestly. You’re the best Morgan in the bunch, Vic, and we’ll have to

stick together. The boys may stick by me, but they would give the whole

thing up if they saw a good way out. You and old Jarred are the only

ones left to uphold the honor of the family.

The child shook the mass of black hair back from her face, and looked

squarely into the old man’s eyes. The concentrated hatred and fury of

three generations gave her the appearance of a witch. Don’t you worry,

grandpa. Let daddy and uncle Bob give up if they want to, but no Wait

will ever cross the line while I am here to help you.

Her grandfather patted her head proudly. That’s the girl. I knew I

could count on you, Vic. Now go in the house, and get some lunch. Then

we’ll go down to the village again. I want to get a look at that

handsome young man myself.

Vic glared at him angrily. I had to say that to tell you what he looked

like. Let him go into the Wait’s store, and I’ll show you what I think

of his looks.

She tossed her head defiantly and stalked into the house

with great dignity.

The old man watched her go with a twinkle of pride in his eye and smiled affectionately. Then he turned away and looked sadly down into the valley. These were indeed sad times when the honor of the Morgans rested on a girl of thirteen, and an old man past sixty, but his gaunt frame straightened unconsciously at the thought, and his chin set all the harder. If the Waits thought that they could walk over him because he was old they were surely reckoning without their host.

While the old man and the child were pledging their everlasting hatred to the Waits, Scott Burton, with puzzled frown, was slowly climbing the mountain road to their cabin. He did not know the location of old Jarred Morgan’s cabin, and probably would have avoided it if he had, for he wanted to think this feud business over before he talked to any of them. Ignorant of how close he was to them, he turned into the woods less than a quarter of a mile below them and sat down with his back against the trunk of a great, wide-spreading beech tree. He was out of sight of the road, and he had purposely chosen the spot in the deep woods to be free from interruption.

So this was the simple little job which the Service had given him to complete before he went back to his old home in the southwest? Why did they always pick him out to unravel some mess? He had never had a job where he could really show what he could do. Always there had been some complication, something outside of the regular line of duty that had taken his whole time and attention. Never had he found himself in a position where he could devote himself to his technical work and show what he knew. Even when he had logged his own land he had found his operations hindered by the bully of the country who had tried to ruin him. His first impulse now was to write to the Service that he did not care to mix up in this mess at all. If they wanted him to go back to his old post, all right; otherwise, he would resign. He had made enough to live on out of his own logging operations, and he could make more the same way. He did not have to worry over these miserable feuds. Two men had already lost their reputations on this job and been run out of the country and....

Right there Scott lost all interest in that line of thought. Was he going to let them run him out of the country? His jaw set at the mere thought of it, and he knew that he would never leave till he had been completely beaten or was carried out in a wooden box. He dropped all idea of giving up the job and settled down to look it squarely in the face.

Just what was this problem anyway? The government owned a big tract of land here, and there was timber on it that was ready to be cut, and it was up to him as supervisor to sell it. It was located on both sides of the valley, part in Wait territory and part in Morgan. Two other men had already tried it, and had failed utterly before they had ever started because they had become involved in this everlasting feud between the Waits and the Morgans.

When he really thought about it, it did not seem to be such an impossible task. Why should he mix up in this feud at all? It looked as though old Foster Wait was to blame for starting it years ago, but it did not matter now who was originally to blame, they were both equally to blame for keeping it up all these years. He would put it up to them squarely that they had to forget the feud, and come together or he would have nothing to do with either of them. Just what could they have to do with it in any event? He did not think, from what he had seen of the country people there, that either family could scrape together enough money to buy the timber on a single acre. He did not see how they could influence the sale one way or the other, and he was not going to let them do it if they could.

When Scott had come to that somewhat Irish decision he felt better. It seemed almost as if the problem had been solved and he began to look about him. His eyes had been fixed absently on the ground all the time and his first upward glance revealed a sight that sent a cold shiver up his back.

A man was sitting on a log not six feet from him, and was staring at him with bright blue eyes. It was startling enough to find any one sitting so close to him when he had thought himself entirely alone, but it was really alarming when the man had a gun in his hand and a large piece of sheet iron on top of his head. At first Scott thought that he must be dreaming, and he blinked his eyes two or three times to try to dispel the illusion, but it would not dispel.

This was really a man. He looked much as other men save for a queer, dreamy look in his eyes, and he was dressed like other men except for his strange head gear. Instead of a hat he was wearing a strange contraption of wood and iron. On the bottom of a sheet of heavy iron about eighteen inches long and a foot wide he had nailed four pieces of wood in the form of a square. This he was wearing on his head like a senior’s mortar board.

All during Scott’s astonished examination, the newcomer sat staring at

him without the slightest expression on his weather-beaten face. He was

so still that he might have been a statue and his unwavering pose added

to Scott’s feeling of his unreality. He finally, after several minutes

of astonished silence, recovered sufficiently from the spell to exclaim

Hello.

He said it in a rather startled tone. It did not sound in the

least like a friendly greeting, but it seemed to be altogether

satisfactory to his visitor. The man’s face relaxed, and a friendly

smile lighted it up. Scott was in hopes that he would remove the iron

hat, but he did not.

So you are the new supervisor,

the stranger remarked in a low,

pleasing voice.

Yes,

Scott replied a little stiffly, for he had not entirely recovered

from his astonishment, and could not keep his eyes off the iron hat,

I’m the new supervisor. And who may you be?

I might be almost anybody,

the man smiled, but I happen to be

Hopwood.

Well, I’m sure I don’t know where you came from, Mr. Hopwood. You just

seemed to appear on that log as if by magic, but I am glad to know you,

all the same.

Not Mr. Hopwood,

the man said solemnly, just Hopwood. Hopwood Wait.

Scott looked at him with a new interest. So this was one of the Waits, the first one he had seen, and he wondered if the iron hat were a part of the family armor. It might have protected him from an airplane attack, but would have been of little use for anything else. He had understood that the Waits did not come over on this side of the valley. Could this man be scouting in enemy territory or had he come in hope of getting a pot shot at a Morgan? He decided to risk a question.

Aren’t you in dangerous territory here?

Hopwood shook his head slowly. No, they all think I am crazy, but I

have more sense than anybody else in the family. I can eat lunch with

Jarred Morgan and supper with Foster Wait, and that’s more than anybody

else can do,

he replied proudly.

Then you don’t believe in this family feud?

Scott inquired eagerly.

Again Hopwood shook his head. Why should I? They will all be killed if

they keep it up. The cemetery is full of them now.

Do you think that they would give it up if they had a good chance?

Hopwood nodded.

What makes you think so?

This man might be able to give him some

useful information even if he was crazy.

Because they are scared,

Hopwood answered promptly. Every one of them

is scared except old Jarred and Vic. They don’t pay any attention to me

and I hear them talk.

Then why don’t they give it up?

Because they are more scared to quit than they are to go on. If they

should quit, old Jarred would kill them all, both Morgans and Waits.

Scott thought for a moment. Old Jarred Morgan seemed to be the key to the situation if this man knew what he was talking about.

Where could I find you if I should need you some time?

Scott asked. He

thought he could see how this man might be very useful to him.

Almost anywhere,

was Hopwood’s unsatisfactory answer.

Scott looked thoughtfully off through the woods a moment wondering what other useful information he could get out of this man, and when he looked back the man was gone.

The disappearance of Hopwood had been so silent and so unexpected that Scott hardly knew whether it had not been a dream after all. He sat still for a moment to see whether he would come back, but, when he did not, he arose leisurely, and began to glance cautiously about him. He did not want to search because he thought that Hopwood must be behind a tree somewhere waiting to have the laugh on him. After all what difference did it make what had become of Hopwood? Scott felt that he had learned all that he could get out of him just now, and he had made up his mind what he wanted to do.

He glanced at his watch. It was a quarter of twelve, and he would be late for his dinner if he did not hurry. He was curious to know how Hopwood had disappeared so suddenly and where he had gone, but he struck out for the road without looking to the right or the left. Just as he reached it he saw the man of the iron hat stroll leisurely around a bend a little way up the mountain, apparently unconscious that he had acted peculiarly, and without a backward glance. The sight of him reminded Scott that he had not found out why this man wore his strange iron hat, and he made up his mind to ask some one the first chance he had.

When Scott reached the hotel after again running the gauntlet of stares in the village there were no signs of a meal in the very near future. The women were talking in the kitchen, but there was no sign of any hurry in spite of the fact that it was already fifteen minutes after the time they had announced for dinner. He went to his room and found it just as he had left it. Either he was expected to make his own bed or the women did not make them till afternoon. He decided to wait and see what would happen.

When the dinner bell finally rang, it was a quarter past one. Scott found himself alone with the station agent. The meal was about the worst he had ever seen. Great cubes of salt pork fat three inches square, boiled and transparent, that might have made an Eskimo’s mouth water, but were impossible for the uninitiated. Corn bread as dry as powder, a sickly looking gravy, and some gluey rice. At first Scott thought that he could not eat any of it, but what was he going to do? This was probably what he would have to eat for several weeks. There was no place to look for anything better. With a desperate look around the table to make sure that he had not overlooked any possibilities, he resolutely helped himself to the rice and the corn bread and waded in. He could swallow these things if he had to, but he could not bring himself even to try the salt pork.

He had been so disgusted with the meal that he had forgotten all about the station agent. Now he recalled that the gentleman had been rather offended at his actions in the morning, and that he had better try to make his peace with him now.

Mr. Roberts, you probably thought me very ungrateful this morning, but

I knew absolutely nothing of this feud here, and could not imagine what

you meant.

The agent answered rather stiffly. None of the government men who have

been here seem to want to know anything about it, but they all learn

something about it sooner or later.

Well, I want to know all I can about it. Up the road this morning I met

Mr. Sanders, and when he asked me that same question about buying at the

stores I asked him to explain. He told me all he could about it, and

then I realized what you meant. I really appreciate your kindness very

much, and want to thank you for trying to warn me. I don’t believe there

are many people around here who would have done it.

The agent was evidently pleased with the apology and melted immediately.

No, I reckon there ain’t,

he said rather proudly. Old man Sanders and

I are about the only ones. The others are all in it up to their necks.

Now that I know about it, I am not going to get mixed up with either

side. They will have to give up their feud and work together like other

people if they want to get in the game.

They will never do that as long as old Jarred lives,

the agent

answered confidently.

That familiar phrase reminded Scott of the strange man with the iron

hat. By the way,

he asked, who is this man Hopwood?

He’s Foster Wait’s nephew. Foster’s father is the man who started the

feud, you know. He had an awful bad temper, and they tell me that, when

Hopwood was a little kid, old Foster hit him in the head with his cane

and he’s been crazy as a loon ever since. Did you meet him at Sanders’

place?

No,

Scott replied, I met him up in the woods.

Thought you might have met him at Sanders’,

the agent said. His

mother was old Sanders’ daughter. What did you think of his hat?

I was just going to ask you why he wears that thing,

Scott said with

renewed curiosity.

He thinks it will keep the devil away.

The agent was delighted with

the opportunity to tell some one of the strange gossip of the country

that he had collected in his ten years of residence. You see when he

grew up he saw that he was not like other people, and they had to give

him some reason for it, so they told him there was a devil in him. He

went right out and built that iron hat and has worn it ever since. Says

he’s going to wear it till they give up the feud.

Doesn’t wear it at night, does he?

Scott asked. It was ridiculous, but

it was so pathetic that he hated to laugh at it.

No,

the agent answered seriously, he doesn’t wear it at night, but he

sleeps on his back with that thing on his chest.

He looked queer,

Scott said, but he seemed to talk reasonably enough.

He said just as you do that they will never drop the feud as long as old

Jarred Morgan lives, but he says the others are all scared and would

drop it if they could.

Sometimes I think he isn’t as crazy as they make out. They talk about

him and in front of him as though he couldn’t understand anything, but

he can tell you every word that they have said for the past five years.

Scott thought for a minute. Do you think it would be safe for me to

make use of him or would that be considered as taking part with the

Waits?

No, that would not tie you up with the Waits. Everybody talks to him,

even old Jarred Morgan. They do not seem to consider him as belonging to

the family, somehow. But you don’t want to be too sure about using him.

If he happened to take a liking to you he will do anything for you, but

if he did not like you this morning you’ll probably never see him

again.

I don’t know whether he liked me or not,

Scott said thoughtfully. He

appeared on a log in front of me so suddenly that I did not see where he

came from, and he got away again in the same way.

Oh, he moves like a shadow in the woods,

the agent exclaimed

enthusiastically. He has any Indian I have ever seen beaten three ways

for woodcraft. He moves about so fast and so silently that a lot of

folks around here think he is a spirit.

It was easy to see from the

agent’s manner that he was not altogether clear on that point himself.

Well,

Scott said, I hope he likes me because it looks as though I

won’t have very many friends around here.

You sure will not,

the agent remarked with decision. You can make

friends with half the people easy enough, but sure as you do the other

half will hate you. If you don’t take up with either side, as you are

planning on doing, likely as not they will all hate you.

Scott sat for a moment dreamy eyed, considering this disagreeable dilemma. When he looked up Hopwood was standing in the doorway, calmly looking at him over the agent’s head. For a moment Scott was too astonished to speak. He wondered if Hopwood had been outside listening, and he thought of what the agent had said about this strange man being a spirit.

Hello, Hopwood!

he exclaimed, and the agent almost jumped out of his

chair.

Hopwood smiled an answer. Is that red-headed man who came on the train

yesterday your boss?

he asked, as though they had been talking for some

time.

Yes,

Scott admitted, he is, in a way.

Well, he’s joined the Waits,

Hopwood remarked.

The announcement almost stunned Scott. He stared wildly at Hopwood for

an instant and then at the agent. What makes you think so?

he asked

dully.

There was no answer, and he found Hopwood had disappeared as suddenly as he had come.

The agent tiptoed to the door and looked cautiously up and down the

porch. Hopwood was nowhere to be seen. He looked back at Scott and shook

his head. Gone completely. Well, whether he is man or devil, I reckon

he is a friend of yours all right.

I guess he is,

Scott replied with a sickly smile, but it does not

look as though my boss thought much of me.

AIDFROM HIS BOSS

Mr. Roberts went back to his office soon after Hopwood’s visit, and was evidently glad of the opportunity to get away. He had spoken derisively of those who thought that Hopwood was a spirit, but he had looked behind him nervously till he was well away from the house.

Scott scarcely noticed that he had gone. He sat with his chin dropped dejectedly on his chest, and stared across the table with unseeing eyes. If what Hopwood had said was true, his troubles there would be greatly increased even if his plans were not completely ruined. It seemed as though some evil genius had brought him to this place, and if he had he certainly must be laughing at the pickle his victim was in.

Scott was so disappointed that he felt almost ready to cry. With considerable difficulty, and the help of old man Sanders and the station agent, he had succeeded in posting himself fairly well on the ins and outs of this feud. After carefully considering the possibility of an alliance with one side or the other he had come to the conclusion that the only safe thing to do was to remain absolutely neutral. He felt confident that if he could keep away from any entangling alliance with either side, he could successfully carry on his work in spite of the feud and might even be able to get these old enemies to patch up their differences. He had still considered that a possibility even though every one said that the feud would never be dropped as long as old Jarred Morgan lived.

And now his superior officer had taken sides with the Waits and spoiled everything.

Scott determined to find Hopwood, learn where Mr. Reynolds was, and know the worst as soon as possible. One of them was right and the other wrong. They must at least get together and agree on a common policy.

So Scott started out in search of Hopwood. He felt sure that he could tell him where to find Mr. Reynolds. The iron hat was nowhere in sight, but Scott felt that he could not be very far away. Surely he would not have come to make such a statement as that and then disappear without waiting to give any explanation of it. Possibly he had gone to one of the stores.

He had started down the village street to investigate when he noticed a motionless figure sitting back of a pile of cordwood a little way back from the street. He instantly recognized Hopwood. Was he hiding from him and would he run away? Scott approached him rather cautiously, but Hopwood watched him calmly and showed no sign of retreating. He rather appeared to be waiting for him.

Thanks for the warning you gave me,

Scott said as soon as he was near

enough to him.

I thought that you would be looking for me,

Hopwood replied with his

usual disregard of preliminaries.

What made you think that I would find you in this out-of-the-way

place?

Scott laughed. Why didn’t you stay at the hotel? I would have

been glad to have had a visit from you.

The more people see me with you the less I’ll hear,

Hopwood answered

cunningly.

Scott started at the flash of wisdom from a half-wit. I guess you are

right,

he replied earnestly. Do you think we are safe here?

Oh, yes,

Hopwood replied confidently. No one can see us here except

from that one place, and no one else will go along that street for half

an hour.

Scott did not waste any time trying to find out how Hopwood knew that.

There was something else that he was anxious to know. Then maybe you

can tell me, Hopwood, what makes you think Mr. Reynolds has joined the

Waits?

He’s been up at the Waits’ nearly all day, and has just about promised

them that you will give them the logging contract.

How do you know he did?

Scott asked incredulously. You were with me

part of the morning, and went up the other mountain when you left me,

he protested.

Hopwood only smiled.

Where is he now?

Scott continued. He could not believe that Hopwood

knew what he was talking about. Maybe he was mistaken. He hoped so.

He is on his way down the mountain with Foster Wait,

Hopwood replied

promptly. He’ll be down here at the store in less than half an hour,

he added, as though he had noticed the doubt in Scott’s face.

Then I guess I’ll wait here till he comes,

Scott said. I don’t want

to be seen now traipsing around the country with Foster Wait.

He’ll have some job to make me give a logging contract to either of

those gangs,

Scott muttered defiantly. Then, after a minute’s silence,

Do you think that either the Morgans or the Waits could carry out a

logging contract if they did get it, Hopwood? Have they the money to do

it?

But there was no answer. Hopwood had disappeared again in his usual silent and mysterious fashion. Scott knew better now than to waste his time looking for him. He fell to brooding over this phase of the problem, and when he looked at his watch it was already ten minutes after the time which Hopwood had predicted for Mr. Reynolds’ arrival. Scott jumped to his feet and hurried out into the open. He was delighted to see Mr. Reynolds coming up the street alone and walked down to meet him.

Mr. Reynolds was a rather effeminate-looking man, over neatly dressed in the very latest cut of riding suit. He affected a rather bored manner. He waved an indolent greeting to Scott.

Hello, there, Burton! I sure am glad to see you. I thought I was going

to have to eat another meal in this beastly hole. Now I can probably

finish up with you in time to catch the afternoon train.

Scott wished that he had caught the train the day before but he did not

dare to say so. Instead he said, Think how long I shall have to eat

here. Better stay awhile. Misery loves company, you know.

Well, I hope you get all the company you want, but it sure will not be

mine if I can help it.

By the way,

Scott asked suddenly, where did you get that cigarette?

Pardon me,

Mr. Reynolds exclaimed, as he fumbled apologetically in his

pocket for the package, but I was under the impression that you never

smoked.

I don’t,

Scott replied. I was only wondering where you bought them.

Oh, here at the store. They carry them, but they are a pretty bum

brand.

Which store?

Scott insisted.

The one on the left there. Hadn’t noticed there were two. What’s the

big idea? You rooting for one of them?

Scott knew that it would be useless to argue with this man. He evidently

had no conception of the situation in the village and Scott did not

think it worth while to try to explain. No,

he replied, I was just

wondering which one I ought to deal with,

which was true enough.

Well, if everything they sell is as rotten as their cigarettes you’d

better try the other one. But come on up to the hotel so that I can go

over things with you in time to catch that train. I think that I have

things lined up here for you in pretty good shape.

How is that?

Scott asked. In spite of the harm this man had done him

he could not help smiling at his unbounded conceit.

Oh, I had a long talk with Foster Wait this afternoon, and fixed it up

with him so that the Waits will take over the logging contract. There is

a big family of them and the labor problem will be settled. No use in

scouring the country the way those other fellows did when it can be

handled so easily locally.

Didn’t sign them up, did you?

Scott asked the question as carelessly

as he could, but he really waited breathlessly for the answer.

No,

Mr. Reynolds answered pompously, I could not very well go into

all those details because I did not have the necessary forms with me. I

only smoothed the way for you a little. Now that I have talked to them

it will be no trick at all for you to get them to sign up and arrange

all the details.

And,

Scott thought, the details would have to include the hiring of

an undertaker to sweep up the remains.

But to Mr. Reynolds he said

nothing. The more he let this man talk the more certain he would be of

getting rid of him on the afternoon train, and that was Scott’s one

ambition now—to get rid of this man at the earliest possible moment.

They walked on up to the hotel and when they came out two hours later Scott was more than ever anxious to see him go. If this man had had anything to do with the business when the two previous supervisors had been run out of the country he could understand perfectly well how it happened. Scott had listened attentively and talked hardly at all.

As they approached the stores Scott saw a good-sized delegation assembled on the porch of each. The Waits looked smilingly elated. The Morgans glared angrily from across the way.

Come on up and I’ll introduce you to these people now if I have the

time.

Scott was determined to avoid this but he did now know how to do it. If he refused, Mr. Reynolds would undoubtedly start an argument which the spectators could not help but understand. Fortunately the train was on time, something which rarely happened, and it whistled just in the nick of time.

As the train pulled out of the station, Scott watched it with a feeling of profound relief, but at the same time he half wished that he was on it. He was rid of Mr. Reynolds, but would he ever be able to get out of the mess into which this man had drawn him?

When the train had disappeared Scott turned to find the station agent close behind him waiting for an opportunity to speak.

I reckon Hopwood was right,

he said with his slow drawl.

What makes you think so?

Scott asked, for he knew that Mr. Reynolds

had not told him.

Three of the Waits have already told me that they are going to get the

logging contract,

he replied.

Oh, they did, did they?

he exclaimed indignantly. Either Mr. Reynolds

must have talked to a gathering of the whole clan or the news had spread

like wild fire over the face of the mountain. Well, they haven’t got it

yet,

he snapped. I guess I’ll have something to say about who gets

that logging contract.

I asked them if you had told them and they said no, but your boss had,

and you would have to do as he said.

Scott’s teeth came together with a vicious snap. They’ll see whether I

have to or not.

He turned abruptly and walked across the tracks toward

the Wait country. No pair of whipcord riding breeches is going to tell

me where to let a logging contract,

he muttered angrily to himself.

He did not know exactly why he had come in that direction. Possibly it was his natural tendency to go straight for his enemy. He did not even realize where he was going; he only realized that he was mad clear through and that he had better walk some of it off before he talked to anybody.

The forest came close down to the edge of the valley on this side and the road was arched over with the beautiful hardwood trees. Scott would have marveled at their size and beauty if he had not been too angry to notice them. The quiet solitude of the steep mountain road was well fitted to smooth a man’s ruffled temper and make him forget his troubles. Everywhere the gray squirrels were chasing each other around the trees in a never ending game of tag, and the birds were singing all over the woods.

Before Scott had gone very far he met two men riding down the mountain

on horseback. They wore the regular uniform of that section, rough

homespun trousers and a black sateen shirt, and carried long

muzzle-loading rifles balanced across their saddle bows. They both

grinned condescendingly at Scott and gave him a careless, Howdy.

He did not think it strange that he should meet two men, but when he met two more a little farther up and they greeted him in the same way he began to comprehend. These were the triumphant Waits on their way to town to celebrate their victory, and they were all laughing at him, laughing because they had overreached him and made terms with the boss that he would have to accept.

The thought maddened him, and by the time he had passed eight more he was so angry that he could hardly see the big fellow who brought up the rear of the last group of four. It would never do to start a row with them now before he was really ready, and yet it was all he could do to hide his fury and return their greetings casually.

The big fellow who had just passed turned in his saddle and looked at

him inquiringly. Weren’t looking for me, were you, sonny?

he called

insolently in a rather thick voice.

Scott’s blood boiled at the tone and wording of the question. He did not

dare look at the man and it almost choked him to answer calmly, Not

to-day.

Well, to-morrow will do,

the man called insolently. You can find me

home most any day.

And the others laughed at the retort.

Scott saw red for a minute and half turned, but he caught himself in time. He would not make much headway in handling this timber sale if he began with a fight in the public road on a somewhat doubtful pretext. If he did fight he ought to have a little better cause than that.

He did not meet any more of the offensive Waits and was beginning to cool off a little so that he could think calmly. Suddenly he stopped with a jerk and turned his startled gaze down the road in the direction all the bands had been traveling. What would be the outcome of this meeting in the village? He had met twelve men on the road and he had noticed eight more at the store when he came by. They were all armed and most likely there would be much drinking. Would they take this opportunity to wipe out the remnant of the Morgans?

He had never seen old Jarred Morgan nor had he ever spoken to any of the family, but right now his sympathy was with them. The picture which old man Sanders had drawn of that lonely old man and a slip of a girl holding the Morgan fort almost alone appealed to him. But what could they do against a gang of twenty? No matter how brave they were, they would be helpless.

Scott’s sense of fair play sent his fighting blood bounding through his veins. He turned resolutely and hurried down the mountain. He thought that he might be able to prevent that crime. He would help to protect that plucky pair if he possibly could, and he would not care what anybody thought about it. He did not admit it to himself, but probably the greatest incentive was the opportunity to fight these insolent Waits. He hurried on without a thought of the possible effects it might have on his plans. Every minute he half expected to hear the shot which would announce the beginning of the fight.

When he came out of the forest at the foot of the mountain, he was relieved to see that everything looked peaceful in the village. The station agent saw him coming and lounged out to the end of the platform to meet him.

Well, they are all in town to celebrate,

he drawled.

I guess they are, judging from the procession I met coming down the

mountain,

Scott growled bitterly. Do you think there will be any

trouble?

The agent looked at him curiously. Oh, I don’t believe they will bother

you any now. They think that you are their friend.

Scott glared at the man indignantly. I am not talking about myself. Do

you suppose I care what that gang thinks of me? But it occurred to me

that they might take this opportunity to catch the Morgans unprepared

and clean up what is left of them.

Oh, you mean that kind of trouble?

and the agent seemed greatly

relieved to find it out. There won’t be any fight unless old Jarred

comes to town.

There will not be any at all if I can prevent it,

Scott replied

resolutely. If there is any fight it will be a fair one and not a

murder of one old man by a gang like that. I wish I could find Hopwood.

You have not seen him, have you?

The agent looked cautiously behind him and shook his head. No, I

haven’t seen him since noon, but that is no reason why he may not be

sitting right here somewhere staring at us.

Scott turned away. Well, maybe I’ll run on to him. He seems to turn up

somehow when he is wanted.

He dreaded passing that crowd at the store and yet he would not have gone home any other way this afternoon for a hundred dollars. There would almost certainly be some impudent remarks and Scott was almost afraid to trust himself, but he made up his mind that he would not fight with them no matter what happened till he had tried to persuade them to drop the feud.

Purposely he kept out of sight behind some trees till he was not more than fifty yards from the store. Then bracing himself for the coming trial he walked casually out of the shadow. His eye took in the situation at a glance, but he could not understand it.

Two lonely men sat silent and sullen on the porch of the Morgan store. At least twenty crowded the porch of the store across the street, laughing and gibing at a burly giant who was dragging a young girl across the street by the hair. The girl’s head was bent down so that Scott could not see her face, but he could imagine her expression. She was not uttering a sound, but she was fighting with the fury of a wildcat.

Scott’s blood boiled at the sight of a man mistreating a girl in this way. Moreover, he recognized the man as the big fellow who had spoken to him so insolently up on the mountain. Even before he realized what he was doing he had covered the short distance and grabbed the man by the arm. He had been a boxer all his life and had won the heavyweight championship at college. He was calm now, as calm as he had ever been when he stepped into the ring. This man was almost twice his size, but he did not even notice it.

Let go of that girl,

Scott commanded, and as he spoke he let go of the

man’s arm. He had grabbed it only to attract the man’s attention. He

knew that he could not hold this man in any such way and he was too good

a fighter to hold on and be jerked off his balance. The steely ring in

his voice was enough to hold any one’s attention now.

The man turned upon him furiously, but he did not let go of the girl. Evidently he had expected to see a Morgan, for when his eyes fell on Scott his mouth dropped open for a moment and he stared blankly.

Did you hear what I said?

Scott insisted with suppressed fury.

A cunning leer came over the man’s sodden face. The spectators at the two stores listened breathlessly.

Quick work to get sweet on her so soon. Get out of the way, sonny, and

go get the papers ready for that logging contract.

Quick as a flash Scott caught the big fellow a tremendous blow on the jaw with the flat of his hand. If the man had been sober he would have hit him with his fist, but he did not want to slug him when he was in that helpless condition, much as he deserved it. Even as it was, the slap was enough. The big man let go of the girl, stumbled, lost his balance and sprawled his length on the ground, where he lay groping helplessly for his gun and muttering curses.

The girl shook her long hair from her face and cast a look of furious

hatred at the fallen foe. Her chest was heaving from the desperate, but

futile, struggle. Turning slowly she swept a contemptuous glance over

the spectators on both porches. Cowards!

she snapped with all the

concentrated contempt she could muster. She turned and walked slowly

down the street with all the dignity of a queen.

Much to Scott’s astonishment not a man had moved a hand to interfere with him. He looked them over slowly to see if they were going to mob him, but nobody moved or spoke. When he had stood there long enough to avoid any appearance of running away, he cast a curious glance at the retreating figure of the girl who had so completely ignored her rescuer, and walked slowly away toward the hotel, trying to figure out what it could all mean.

As he turned the corner of the hotel he almost laughed aloud. He was thinking what the Waits must think of his friendship now.

When Scott entered the hotel he was still thinking what it could all mean. Why were the men of both factions quietly looking on while a big burly drunkard dragged a child around the street by the hair? If the girl was a Morgan why had the Morgans let such an act go unchallenged? If she was a Wait why had not the rest of the gang protected her? He started. Perhaps it was the man’s own child. No matter. No man had a right to drag his own child around by the hair. Well, when the station agent came to supper he could probably explain things.

But the station agent did not come to supper and Scott ate the atrocious food in lonely state still trying to solve this mystery. In any event he had shown the Waits just how much they could count on his friendship and that was worth something. It was also some satisfaction to know that they were probably as much troubled as he was.

Alone in his room he pondered the problem for an hour without coming any nearer to a solution. Finally the suspense became unbearable. He determined to go to old man Sanders and see if he could offer any explanation. It was growing dusk when he went out and objects seemed a little indistinct in the distance. He glanced toward the place where Hopwood had been waiting for him in the afternoon, but there was no trace of him now.

Both stores apparently were deserted. Scott had not seen a soul when he turned into the road which led up to Sanders’ little cabin. He thought that he had never known the woods to be so silent. It seemed as though every living thing must have left the country. But there was a light in Sanders’ cabin. The full moon peeped at him over the trees behind the house. He knocked on the door and heard the old man shuffling across the floor to open it.

Good evening,

Scott said as the door swung wide. You see I have come

back to you for advice pretty quick.

Come in, come in,

the old man said cordially. Glad to see you.

He

motioned Scott to one of the old-fashioned chairs. When they were

comfortably seated he spoke again.

You said you came here for advice. Let me give you a little before I

forget it. It happens to be perfectly safe for any one to knock on my

door at any time of the day or night, but don’t try it anywhere else.

You would probably find yourself looking down the barrel of a gun if the

dogs did not chew you up first. It is the custom in this country to

stand outside the gate and shout.

Thanks,

Scott replied gratefully. I am very anxious to learn the

customs of this country. There seem to be some customs here I do not

understand. That is what brought me up here to-night. What does it mean

when a big bully of a man hauls a girl around the street by the hair

while twenty others look on and do nothing?

The old man straightened up in his chair. What’s all this?

he asked

sharply.

Scott explained as fully as he could and the old man listened breathlessly to every word. When Scott had finished his story the old fellow sank back in his chair with wrinkled brow.

So that was how it happened,

he muttered to himself. The girl has

more sense than I thought she had.

Then he spoke aloud to Scott. I

heard a little something of this but I did not know that you had

anything to do with it. It’s a wonder to me that you are here to tell

it.

Scott misunderstood him. I admit it was a little hasty,

he replied

with dignity, but I am not ashamed of it.

The old man laughed aloud. No, no, you have nothing to be ashamed of. I

am only surprised that Foster has not killed you before this. Be on your

guard, for he will certainly try it.

Tell me about it,

Scott said. What was going on? I could not make

head or tail of it.

Mr. Sanders thought for a moment. Must have seemed queer to you. Would

to anybody. You see Foster Wait, he was the big fellow, was drunk as he

usually is when he has any excuse for it at all. He happened to see Vic

Morgan there in the village and could not help poking some fun at her

about the logging contract. They all love to tease her just to see her

spit fire. She flew into a tantrum just as she always does, ran out to

the middle of the street, which is the dividing line between Morgan and

Wait territory, and told him what she thought of him and the whole Wait

tribe. She said herself that she cursed Foster pretty bad.

You see she felt safe because the Waits never come past the middle of

the street. But, as I said, Foster was drunk and he reached over the

line and grabbed her. Probably just wanted to spank the kid for a joke.

Vic could not see the joke and bit his thumb. Hurt him pretty bad, I

reckon, and made him mad. He has a terrible temper like his father. He

grabbed her by the hair for a safe hold and then you came along.

But how could those men there at the Morgan store see a Wait treat a

member of their family in any such way as that?

Scott protested.

Because Jim don’t believe in keeping up the feud, and it makes him mad

every time Vic stirs things up that way. Probably thought it served her

right.

So that child is Vic. And she is the only supporter old Jarred has. Who

is she, anyway?

Scott asked.

She is the daughter of Jim Morgan there at the store, but she spends

most of her time up on the mountain with her grandfather. She and the

old man are great chums.

Just one more question,

Scott said, or rather two more and then I’ll

let you go to bed. Why didn’t any of the Waits interfere when I knocked

their leader down? I did not know who he was or I might have been

scared.

Because they don’t like him. He is a regular bully, and they were

probably glad to see somebody stand up to him. Besides, they are

expecting a good deal from you.

Scott ignored the last remark. And my last question. How did you find

out about it so quickly?

The old man hesitated an instant. That is the part that puzzled me. Vic

stopped in here and told me about it herself. That would not have

surprised me because she usually tells me everything, but she asked me

not to let her grandfather hear about it if I could help it. That is

what astonished me. Ordinarily she would have gone to her grandfather on

the run and wanted him to kill the whole tribe. He’ll try to do it too

if he ever hears about this and his own tribe, too, for letting it

happen. I think Vic must have realized that. Didn’t know the kid had so

much judgment. She did not say anything about your rescuing her,

either,

he mused.

Scott was thoughtful a minute. Well, I certainly appreciate your help,

Mr. Sanders. I think I understand it a little better now, but,

he added

slowly, I don’t think I shall ever understand how a father could sit

still and see a drunken man treat his daughter like that.

And he arose

to take his leave.

Old Jarred wouldn’t understand it, either,

Mr. Sanders said, as he

rose to show his guest to the door. I wish you would help me to keep

him from finding it out. The kid does not want him to know, and I like

her.

So do I,

Scott replied. She fought like a wildcat. I admire nerve in

anybody. I admire the old man, too, for holding out alone against that

big gang, and I am going to protect him all I can.

He was out on the porch now, and the old man was standing in the

doorway. Good night, and thank you again.

Good night, and be careful,

the old man warned him. Foster Wait is a

dangerous man and he’ll never be satisfied till he gets his revenge for

this insult. He won’t stop at anything and you must be on your guard all

the time.

I’ll try to watch him,

Scott replied simply.

Do that,

the old man called. I’ve taken a fancy to you and I don’t

want to see you shot for nothing.

The door closed before Scott could reply and left him alone in the moonlight. He felt his loneliness then in that unfriendly country and was grateful to the old man for his help and his friendship. With a sigh he turned down the mountain road pondering on the strange story he had heard. He could see how the news of this encounter might mean the disruption of the whole Morgan faction if it were ever revealed to old Jarred, and the girl must have seen it too.