Patient waiting for the earth to bloom develops a little child spiritually.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Montessori children, by Carolyn Sherwin Bailey This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Montessori children Author: Carolyn Sherwin Bailey Release Date: November 29, 2018 [EBook #58379] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MONTESSORI CHILDREN *** Produced by Turgut Dincer and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Patient waiting for the earth to bloom develops a little child spiritually.

MONTESSORI CHILDREN

BY

CAROLYN SHERWIN BAILEY

ILLUSTRATED FROM SPECIALLY POSED PHOTOGRAPHS

NEW YORK

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY

1915

Copyright, 1913, 1914,

BY

THE BUTTERICK CO.

Copyright, 1915,

BY

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY

Published February, 1915

THE QUINN & BODEN CO. PRESS

RAHWAY, N. J.

As a student of child psychology and always most deeply interested in the welfare problems that confront us in connection with the upbringing of little children, I went to Rome in 1913 to study, first-hand, the results of the Montessori system of education. A great deal had been written and said in connection with the technic of the system. Little had been given the world in regard to individual children who were developing their personalities through the auto-education of Montessori. I wished to observe Montessori children.

Through the gracious courtesy of Dr. Montessori, I was given the privilege of observing in the new Trionfale School where the method could be watched from its inception, and in the Fua Famagosta and Franciscan Convent Schools. I was also given the privilege of hearing Dr. Montessori lecture, elucidating certain problems in her theory of education not previously given publicity.

I found little ones of three, four, and five years,[iv] surrounded by the many observers of the first international Montessori training class, yet so marvelously poised and self-controlled that they went through the days as if alone. I saw such proofs of the integrity of the system as the instances of Otello, Bruno, and others.

The pages which follow constitute a series of pictures of real child types showing Montessori results. As a record of results, I hope they may contribute to the world’s greater faith in the discovery of Montessori—the spirit of the child.

Carolyn Sherwin Bailey.

New York, 1915.

| PAGE | |

| Dr. Montessori, the Woman | 3 |

| With Margherita in the Children’s House | 13 |

| Showing the Unconscious Influence of the True Montessori Environment. | |

| Valia | 26 |

| The Physical Education of the System. | |

| The Freeing of Otello, the Terrible | 39 |

| Montessori Awakening of Conscience Through Directed Will. | |

| The Christ in Bruno | 54 |

| About the New Spiritual Sense. | |

| Mario’s Finger Eyes | 67 |

| Montessori Sense-Training. | |

| Raffaelo’s Hunger | 81 |

| Color Teaching. Its Value. | |

| The Going Away of Antonio | 94 |

| Directing the Child Will. | |

| Andrea’s Lily | 108 |

| The Nature-Training of the Method. | |

| The Miracle of Olga | 119 |

| Reading and Writing as Natural for Your Child as Speech. | |

| Clara—Little Mother | 135 |

| The Social Development of the Montessori Child. | |

| Piccola—Little Home Maker | 148 |

| The Helpfulness of the Montessori Child. | |

| Mario’s Plays | 163 |

| Montessori and the Child’s Imagination. | |

| The Great Silence | 176 |

| Montessori Development of Repose. |

| Patient Waiting for the Earth to Bloom Develops a Little Child Spiritually | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| Back-yard Apparatus for the Physical Development of Children Is Valuable | 28 |

| An Important Physical Exercise of Montessori | 30 |

| Hand and Eye Work in Connection in Exercises of Practical Life | 32 |

| Walking upon a Line Gives Poise and Muscular Control | 34 |

| The Kind of Toy Dr. Montessori Recommends for Physical Development | 36 |

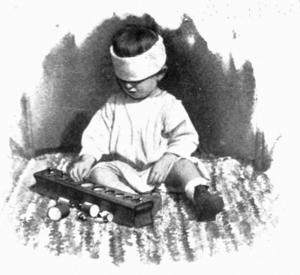

| Replacing the Solid Insets by the Sense of Touch Alone | 70 |

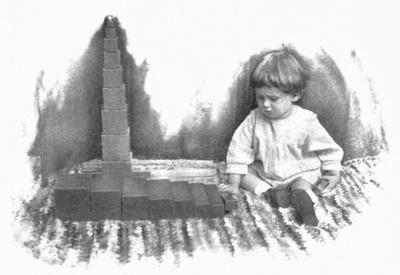

| Building the Tower and the Broad Stair | 70 |

| A Fineness of Perception Is Developed by Discriminating Different Textiles Blindfolded | 74 |

| Perfecting the Sense of Touch with the Geometric Insets | 76 |

| To Match the Colors Two by Two Is the First Exercise | 84 |

| Grading Each Standard Color and Its Related Colors in Chromatic Order | 88 |

| All the Colors of Nature May be Found | 88 |

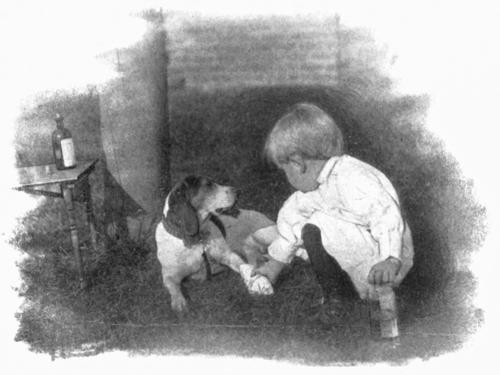

| Every Child Should Have a Pet | 110 |

| The Loving Care of a Dumb Animal Results in Child Sympathy | 114 |

| To Feel that Something Is Dependent upon Him for Care and Food Helps a Child to Reverence Life | 116 |

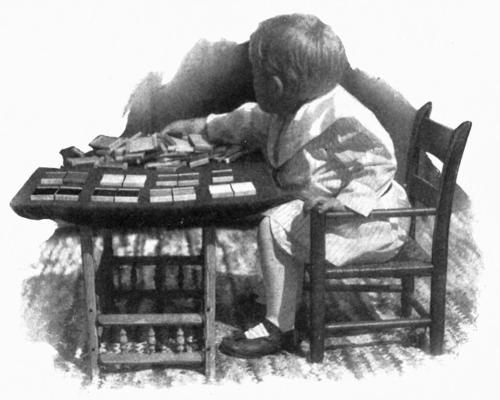

| Building Words with the Movable Alphabet | 122 |

| Learning the Form of Letters by the Sense of Touch | 126 |

| Filling in Outlines with Color to Gain the Muscular Control Necessary for Writing | 126 |

A holiday in Rome, the Eternally Old, the Eternally Young. A long, sun-dried street that flanks the Tiber is gay with fruit venders who push along their carts of gold oranges, strings of dates, and amber lemons. Italians of the wealthy class mingle in friendly fashion with the native-costumed peasants. Someone starts a snatch of song; a dozen passersby take up the strain. Where the chariots of the Cæsars rattled by in yesterday’s centuries, there rises a stately row of stucco apartment mansions with terraced gardens where pink roses and purple heliotrope run riot over the hedges and silver-toned fountains sing, all day long, their tinkling tunes.

Leaving the gay, bright street, you ring the electric bell at number 5 Principessa Clotilde.

“Is the Dottoressa at home, or is she keeping holiday, too?” you ask of the porter. He laughs, motioning you to an almost human elevator that lifts itself and will stop at whichever floor you ask it.

“Yes, La Dottoressa Montessori is in—in fact, she is nearly always in because of the many people, mainly Americans, who come to see her. And the children come daily to see her as well.” The porter shrugs his shoulders, uncomprehendingly, as you enter the elevator and stop at the fourth floor. The popularity of this tenant of his is a matter of wonder to the porter.

As a low-voiced maid opens a great carved door and you find yourself in Dr. Montessori’s apartment, you hold your breath at the modernism of it. Plain white woodwork, fine old rugs covering the stone floors, the soft tan walls covered with a few beautiful tapestries; French furniture and electric lights. The reception room in which you wait might be that of an American home, but a glance out of the open window unfolds to you the heart of the tenant. While her home is in one of the most beautiful and cultured centers of Rome, Dr. Montessori sees daily a tiny, narrow Roman alleyway where the “people” live like bees in a hive and the doorsills throng with little children and their voices rise to her every hour of the day.

But you hear a step. You turn. You are face to face with Maria Montessori.

At first you have no words. You have seen her picture in America, but it gave you no conception of the fine, chiseled beauty of the woman who stands before you dressed in severe black that accentuates the marble of the classic features, the depth of the far-seeing, dark eyes. Poise, grace, self-control, sympathy, love of humanity are written on the face. It is as if all the Madonnas of the imagination of the old Italian painters had come to life in La Dottoressa. Overpowering the first glance of courteous welcome, though, that accompanied her outstretched hand is a look of stern query.

Why have you come? Are you another of the curious visitors who have besieged her from almost every nation the past year to try and grasp in a day her method of teaching that she gained only through twenty years of patient, tireless scientific study of the child mind, she seems to ask. But your words come like a torrent now. You assure her that you have made this pilgrimage to Rome, not as an individual, but as the voice of thousands of mothers who have children to be educated. They ask Dr. Montessori, through you, for her message to the American people. As you linger[6] over the words, madre, mother, and bambino, baby, Dr. Montessori smiles. You have set her doubts at rest. She talks fast, eloquently, in her musical Italian, and you listen, thrilled, fascinated. Often you are interrupted, but always by children. Lovely, dark-eyed, courteous little Roman boys and girls they are. They come from you know not where, are admitted to Dr. Montessori’s apartment quite as if they were adult visitors, and after they have greeted her in their graceful, polite fashion, they quietly run about the room or sit in groups talking together as if the apartment were the popular meeting place for all the children of the neighborhood. You find their interruption and their presence a help instead of a hindrance to your interview. They illustrate by their loving friendship for La Dottoressa and each other, and by their complete self-control, the message that Dr. Montessori gives you to carry back to the American people.

She would liberate the children.

The American people are free, but American children are not.

We have lost sight of the Republic of Childhood, she says. Through forcing our adult[7] standards of conduct and teaching upon children, we have closed the gateways of their souls. We must believe that every child, well-born into the world, is going to be good and happy and intelligent if we as parents and teachers give him a fair chance. We must stop commanding our children. Instead, we will lead them.

Dr. Montessori tells us that we are undergoing a slow but certain change in the social structure of society. Woman is being emancipated from her domestic slavery of yesterday. We are creating a new and more healthful environment for the laboring man. But the American child is still a slave to the capricious commands of his parents, which claim his soul and prevent his free, natural development to his best manhood. In school, too, children are still bound.

The vertebral column, Dr. Montessori tells us, which is biologically the most fundamental part of the human skeleton; which survived the desperate struggles of primitive man against the beasts of the desert, helped him to quarry out a shelter for himself from the solid rock and bend iron to his uses, cannot resist the bondages of the present-day school desk. Curvature of the[8] spine is alarmingly prevalent among children and is increasing. Instead of resorting to surgical methods, corsets, braces, and orthopædic means for straightening child bodies, we should try to bring about some more rational method of teaching that children shall no longer be obliged to remain for the greater part of the day in such a pathologically dangerous position.

Not only do we hurt child bodies by the confinement of the school desk, but we wound their souls by ever offering rewards and punishments, by insisting upon such long periods of absolute silence as are demanded in our schools, and by imposing upon children a program of instruction that is built, often by law, to be followed by large groups of children. The normal child is he who finds it impossible to follow a program of school work or to obey, unquestioningly, the arbitrary commands of his parents. He must follow his own bent, providing he does not interfere with the freedom of others, if he is to dig out his own life path. The abnormal child is the one who never resists; he is the child who, without dissent, obeys all adult commands.

So Dr. Montessori, who has discovered a method of free teaching by means of which children from two and a half to five develop naturally and happily along lines that culminate in a spontaneous “explosion” into self-taught reading and writing at four and five years, speaks to the American parent.

She begs us to give our children the freedom that is the American nation’s boast. Not the freedom that would lead to disordered acts, but that liberty which means the untrammeled exercise of all the moral and intellectual powers that are born with the individual.

About twenty years ago Maria Montessori, a beautiful young society girl of Rome, startled Italy by receiving with honors her degree as Doctor of Medicine. The Italian girl of the cultured classes is essentially a home girl. She studies at home, she embroiders, she plays with flowers, she is introduced to society—then she marries. That Maria Montessori should desert the quiet, rose-strewn paths of Roman débutantes and, after taking her degree, act as assistant doctor in the Psychiatric Clinic of the University of Rome, startled all Italy.

Her work at the clinic led her to visit the general insane asylums, and she became deeply interested in the deficient children who were housed there, with no attempts being made to educate them. As she studied these helpless little ones, the idea came to her that it might be possible, by putting them into better surroundings, and giving them opportunity for free gymnastic activities and free use of the senses, to educate them. She gave up medicine for teaching and again startled Italy—and the world. Her deficient children learned to read and write, easily and naturally, and took their places beside normal children in the municipal schools.

Then Dr. Montessori carried her method of physical and sense education a lap farther. If this method stimulated to action the sleeping mind of a deficient child, might it not save time and energy in the teaching of normal children, she asked herself. At that time, the Good Building Association of Rome was tearing down the squalid, disease-filled houses of the poor of the San Lorenzo Quarter and putting up in their places hygienic model tenements. Dr. Montessori arranged to have the children of each tenement gathered in[11] one room of the basement, where large, free spaces, didactic apparatus, hot meals, and gardens would make it a Children’s House. She applied her method in numerous of these Children’s Houses and in the beautiful convent of the Franciscan nuns on the Via Giusti.

Again the miracle happened. Children of four began to read and write, having taught themselves. There were other wonders, too. These Montessori-trained children were self-controlled, free, happy, good. To-day there are Montessori mothers all over the world.

To furnish the right environment for the expanding of the child soul, Dr. Montessori urges that every home be transformed into a House of Childhood. It will not consist alone of walls, she tells us, although these walls will be the bulwarks of the sacred intimacy of the family. The home will be more than this. It will have a soul, and will embrace its inmates with the consoling arms of love. The new mother will be liberated, like the butterfly bursting its winter cocoon of imprisonment and darkness, from those drudgeries that the home has demanded of her in the past, leaving her better able to bear strong children, study those[12] children, teach them, and be a social force in the world.

The new father will cultivate his health, guard his virtue, that he may better the species and make his children better, more perfect, and stronger than any which have been created before.

The ideal home of to-morrow will be the home of those men and women who wish to improve the human species and send the race on its triumphant way into eternity.

So Dr. Montessori, physician, psychologist, teacher, lover of children, and womanly woman, speaks to us.

As one says addio and leaves her and goes down into the blue, star-filled evening of the Eternal City, the night seems to be charged with a new mystery. Rome, who holds in her beautiful hands such good gifts for us—art, sculpture, history, painting—now offers to us another. Stretching farther than the moss-grown stones that line the Appian Way, she shows us a new road—the way that leads to the soul of a little child.

It is so early in the sweet, perfume-laden Italian morning that the dew is still hanging in diamond drops on the iris and roses in the garden of the Casa dei Bambini of the Via Giusti, Rome. The great white room, with its flooding sunlight and host of tiny, waiting chairs and tables, is empty, quiet, calm.

Margherita stands a happy second in the wide-arched doorway that makes room and garden melt into one fragrant, peaceful whole. A wee four-year-old girlie is Margherita, big-eyed, radiant with smiles, and tugging a huge wicker basket of lunch that is almost as large as she. She is the first baby to arrive at the Children’s House. Ah, but that does not ruffle her composure. She is already alone in her newly-found freedom of spirit. She needs no teacher.

She places the lunch basket on a waiting bench, crosses to a wall space where rows of diminutive pink and blue aprons hang at comfortable reaching distances for little arms. She finds her own apron, wriggles into it, buttons it at the back. She is ready for the day.

What shall come first in Margherita’s day? So much is in store for her, waiting for her eager finger tips, her electric-charged soul. As her great brown eyes slowly trail the room and the colorful garden outside, it is as if she were making a soul search for that “good thing” which will be her first silent teacher. Her glance lingers on the terraced rows of flowers, the tinkling fountain in the center. She has found the object of her search. She runs—no, she floats, for such complete physical control of her limbs has this four-year-old baby—to the garden, and kneels there, looking up at a redolent, yellow rose that has opened in the night. She does not touch it; she only looks and breathes and wonders. She has watched for this unfolding daily, waiting with sweet patience for the branch to burst into bud and the bud to unfold into bloom. She has tugged a vase of water each morning to offer drink to the roots. Now her[15] patience and her service are rewarded. As she kneels there looking up into the petals of the gold flower, her small hands clasped over her breast with devotional ecstasy, Nature opens her heart to the heart of a little child.

Many rapturous minutes the baby kneels. Then she flies back to the room again and glances at it with the critical eye of a housekeeper. Here she flicks away a speck of dust, there she picks up a scrap of paper from the stone floor. She peeps into the wall cabinets that hold the Montessori didactic materials to see if the gay buttoning, lacing, and bow-tying frames, the fascinating pink blocks of the tower, the frames of form insets are all in their places. In the meantime the Signorina directress comes. Bruno, of five, arrives, bringing with him his two-and-a-half-year-old brother. More toddlers trail in, two and a half, three, four, four and a half years old, and button themselves into their pink and blue aprons. Independent, polite, joyous little children of the Cæsars they are, each with his or her own special happy task in mind in coming to the Children’s House this blue day.

The wee-est toddlers drag out soft-colored rugs,[16] orange, dull green, deep crimson, and spread them on the wide white spaces of the sun-flecked stone floor. Here they build and rebuild the enchanting intricacies of the tower of blocks, the broad stair of blocks, and the red and white rods of the long stair, chanting to themselves as they unconsciously measure distances and make mental comparisons: “big, little; thick, thin; long, short.”

Children of three and a half and four take from the cabinets boxes of many-colored, silk-wound spools, which they sort and lay upon the little tables in chromatic order until a rainbow-tinted mass lies before their pigment-loving eyes. From the bright scarlet of poppies to the faint blush of pale pink coral, from the royal purple of the tall, spiked Roman iris to the amethyst tint of a wild orchid, they make no mistake in the intermediate color gradations. Other children of four and over finger with intelligent, trained skill the geometric forms; circles, triangles, squares that they are learning to recognize through the “eyes in their fingers,” and which will help them to see with the mind’s eye the form that makes the beauty of our world. Small Joanina, in her corner, runs her forefinger with the greatest delicacy of touch[17] a dozen times around a circle. Then she fits it in its place in the form board, takes it out and fits it in again. Then she looks up, a new light in her eyes, darts out into the garden and walks slowly about the fountain, running her finger around its deep basin.

“Signorina, Signorina!” she calls. “The fountain is a circle. I can see a pebble that is a circle, too. I see many circles!”

So the children learn through the exercise of the senses.

But Margherita?

All this time she has flitted from one task to another. She found an outlined picture of clover leaves and colored it with dainty pencil strokes, making the leaves deep green and the background paler, and handling her pencil with careful skill. Then she took a box of white cards on which are mounted great black letters, cut from fine sandpaper. Holding each card in her left hand, she traced the form of the letter with her right forefinger, closed her eyes, traced its form again, repeated the letter’s name to herself in a whisper, sat silently a second.

As the Signorina directress moves from child[18] to child, smiling encouragement, showing Bruno’s baby brother’s clumsy fingers how to slip a button through a buttonhole, helping Joanina to find a new form, the square, she watches Margherita.

“This may be a white day in the child’s mind growth,” she thinks, but she does not suggest, or hurry the miracle. She only waits, hopes, watches.

Silence is written on the blackboard. Three hours have passed in which over thirty children, barely out of babyhood, have worked incessantly at many different occupations, have moved gracefully and with complete freedom about the room, have changed occupations as often as they wished, have not once quarreled. But now, out of the ordered disorder, comes a marvelous hush. No word is spoken, but one baby after another, glancing the written sign, drops back with closed eyes into a hushed silence in which the whir of bird wings in the garden, the fluttering of casement hangings, the far-away sound of a bell are audible. Even Bruno’s baby brother struggles not to make a clattering noise with his little chair. No one has said to this two-year-old, “Be still.” Rather, has he been inspired to feel stillness.

Out of the restful calm of the room comes the[19] whispered call of the Signorina: “Bruno, Piccola, Maria, Joanina, Margherita!” Lightly, noiselessly, joyously the children come and huddle in a hushed group about the directress. She has called to the soul of each child, she has commended them for their self-taught lesson in control.

As the work with the didactic materials is taken up again, Margherita sits in a little chair for a space, quiet, reflective. Her lips move, her fingers trace signs in the air and on the table before her. The Game of Silence has helped this four-year-old with her spirit unfolding. Now, with a sudden impulse, she darts to the blackboard, seizes a piece of chalk, writes.

“Ma-ma! Ma-ma!”

Margherita writes it a dozen times in clear, flowing script with breathless, eager strokes.

“Signorina, Signorina, I write—I write about my mother. I write!” she joyously interpolates.

The other children look up with sympathetic interest, some leaving their work to crowd about the victorious Margherita. All of them voice their sympathy.

“Margherita writes,” they say. With the older ones who have already reached this wonder[20] lap in their education there is a note of nonchalance.

“We also write,” they seem to say. With the tiny ones there is a note of hopeful promise.

“Some day we, too, will find that we can write,” they seem to say.

Margherita covers the blackboard with clear, big script. She erases it all for the sheer joy of assuring herself that she is able to write it all over again. When the luncheon hour comes, she looks back longingly at the blackboard as she lays plates on the little tables with dainty precision, places knife, fork, and spoon deftly, carries five tumblers at a time on a tray without dropping one, and passes a tureen of hot soup that is so large as to almost hide her small self. Even the happiness of being one of such a happy “party,” of eating one’s lunch of peas and sweet wheat bread and soup in the Children’s House, does not wholly satisfy Margherita to-day. Her big brown eyes are raised continually to her first written word.

Luncheon over, the children, with balls, hoops, and toys, romp out for an hour’s play in the garden.

“Margherita,” Bruno calls. “Come, we will have The Little One for a donkey, and I will harness him with you, who may be the horse!”

But the little girl, usually the first to start a game, does not hear. She is seated under the rosebush as if she were telling her rose the wonder that has come to her to-day. She and the rose have unfolded together. So it is with all Montessori children. They open their souls as flowers do, naturally, freely, surely.

Margherita is your child as well as the precious bambino of her Roman mother. Children the world over, from sun to sun, from pole to pole, are the same in these plastic first years of mind growth. They have the same insatiable desire to do, to touch, to be free in activity. Not always understanding the little child’s hereditary way of grasping knowledge, we wound his spirit by crushing these natural instincts. We say, “don’t touch,” “be still,” because the activities of our small Margheritas and Brunos interfere with our adult standards of living.

Dr. Montessori has discovered that to say, “don’t touch,” “be still,” to a child is a crime.[22] Such commands are the keen-edged daggers that kill the child soul.

It is possible that some time will elapse before Dr. Montessori’s system of setting the clockwork of the little child’s mind running automatically, of opening the floodgates of the child soul can be adopted in their entirety in our American school. We are so used to thinking of a school as a crowded place of many desks, where children must remain, bound physically and mentally by the will of the teacher and the relentless course of study, that a Montessori schoolroom where, as Dr. Montessori herself expresses it, children may move about usefully, intelligently, and freely, without committing a rough or rude act, seems to us impossible. We even prescribe and teach imaginative plays to our children—as if it were possible for any outside force to mold that wonderful mind force by means of which the mind creates the new out of its triumphant conquest of the world through the senses.

Ideal Montessori schools may be our hope of to-morrow, but to make of a home a Children’s House is the fact of to-day.

To bring about Montessori development in the[23] home is not alone a matter of buying the didactic materials and then offering them to your Margherita and looking for their future miracle working. This would mean stimulating lawlessness instead of freedom. Many of our children already play with squares and circles without seeing how squares and circles make beauty in the architecture of our cities. Many of our children grow up side by side with opening roses without unfolding with them. We would most of us rather button on our babies’ aprons, tie their bibs, feed them, than lead them into the physical independence that comes from doing these things themselves. We wish children to be obedient, but instead of establishing principles of good in their minds which they will follow freely, if we only give them a chance, we command, and expect unreasoning obedience to our injustice.

A Children’s House in every home will be a place where the mother is imbued with the spirit of the investigator. She watches her children, asking herself why they act along certain lines. She leads instead of ruling. She will teach her children physical independence as soon as they can toddle. To know how to dress and undress, to[24] bathe, to look quickly over a room to see if it is in order, to open and close doors and move little chairs, tables, and toys quietly, to care for plants and pets—these are simple physical exercises which help to keep children free and good. She will provide her Children’s House with materials for sense-training. She will lead her children by simple, logical steps into preparation for early mastery of reading and writing.

The first step, however, in giving the American child a chance to develop along the self-active, natural lines of Margherita is to fill our homes with the spirit of Montessori. We will have unlimited patience with the mistakes and idiosyncrasies of childhood, remembering that we do not aim to develop little men and women but only as nearly perfect children as we can. We will endeavor to surround ourselves with those influences of love and charity and beauty and simplicity which it will be good for our children to feel as well. We will offer the children the best food, the greatest amount of air, the brightest sunshine, the least breakable belongings, the most encouragement, the minimum of coercion.

Our attitude toward the child will be that of[25] the physician to whom the slightest variation of a symptom is a signal for a change of treatment, to whom a fraction of progress measures a span. A careful home record of the child’s mental, moral, and physical gain should be kept, and it will be radiantly discovered that the removal of the burden of force and coercion from the shoulders of the little child will give him an impetus, not only to mind growth, but to the attaining of greater bodily strength.

Much misunderstanding of the system of Montessori has come about through our too lavish interpretation of the word freedom as lawlessness. It should be interpreted, rather, as self-direction. The home in which the children are provided with good living conditions, in which it is made possible for them to grow naturally, where their longing to see and touch and weigh and smell and taste is satisfied as far as can be arranged, and where they are led to be as independent of adult help as possible, is laying the foundation for the education of Montessori.

Valia was her mother’s little stranger. Although the mother had borne and fondled and bathed and clothed and undressed the pink flesh that held the baby soul, she did not know that flesh. And Valia grew to be three years old, fat and good, but with little bent limbs and a tired-out spine and clumsy, fumbling fingers.

“Sit in your chair, Valia. That is what chairs are made for,” Valia’s mother admonished at home when the baby joyfully pranced across the floor on “all fours” or lay prone at play with her toys.

“Walk in the garden path like a little lady,” she urged, when Valia, taken out for a walk, climbed to the lowest railing of an adjacent fence and walked along it, sideways, or hung from the top, her fat legs swinging in the air.

“Do not jump; to jump is noisy and unbecoming[27] in little girls,” the mother commanded, as Valia, brought to the Trionfale Children’s House in Rome, hopped gayly up and down the wide stone steps.

But the directress of the school had no word of reproof for baby Valia. She looked at the bent legs that could hardly hold the weight of the plump body, she glanced at the powerless baby hands that could not clutch with any force the handles of a toy wheelbarrow which another child offered Valia for her play.

“You have not noticed the baby’s limbs,” the directress suggested.

The mother’s eyes trailed the school yard where Valia struggled to keep up with the other sturdy little men and women who trundled their toy wheelbarrows up and down in long happy lines. She shrugged her shoulders.

“Perhaps they are crooked, but what can one do to the body of a bambino but feed and cover it?” she asked in discouraged query.

“Ah, La Dottoressa tells us,” the directress replied simply.

“We can know the body of the little child.”

The education of Valia’s muscles was begun that very day, that instant.

Back-yard apparatus for the physical development of children is valuable.

In the school garden the little maid found her way with the other children to an immediately fascinating bit of gymnastic apparatus; a section of a low fence it looked, its posts sunk deeply into the ground so as to make it strong and durable. It was the right height for small arms to reach the top rail, which was round, smooth, and easily grasped by small hands. Here Valia hung, her limbs suspended and at rest, for long periods. Sometimes she pulled her body up so that her waist was level with the upper railing. It was a new game, one could climb a fence without being chided for it. Valia did not know, but Dr. Montessori did, that little children climb fences, pull back when we lead them, and try to draw themselves up by clinging to furniture because they need this form of physical exercise to bring about harmonious muscular development. Valia’s body was developing at an enormously greater rate than her limbs. The height of your baby’s torso at one year is about sixty-five per cent. of its total stature, at two years is sixty-three per cent., at three years is sixty-two per cent. But the limbs[29] of the baby, ah, these develop much more slowly. To hang from the top railing of a fence straightens the spine, rests the short limbs by removing the weight of the torso, and helps the hands to prehensive grasping. So Dr. Montessori invented and uses this bar apparatus with the children at Rome and recommends its use in American nurseries and playrooms.

The next Montessori exercise for Valia was a simple, rhythmic one—walking on a line to secure bodily poise and limb control.

It was just another game for a child, full of happy surprise, too, for she never knew when the sweet notes of the piano in the big rooms of the Children’s House would tinkle out their call to the march. But when the pianist played a tune that was simple and repeated its melody over and over again and was marked in its rhythm, Valia and Otello and Mario and all the other babies put away their work and fluttered like wind-blown butterflies over to the place where a big circle was outlined in white paint on the floor. To march upon this line, now fast, now slowly, sometimes with the lightness of a fairy and then with the joyously loud tramp of a work horse, oh, how[30] delightful! Sometimes the music changed to the rhythm of running or a folk-dance step, and this gave further delight to the little ones.

At first, Valia could not find the white circle of delight. Her fat feet refused to obey the impulse of her eagerly musical soul. But with the days she found poise and grace and erectness and the crooked limbs began to straighten themselves.

She sat, for hours at a time, in a patch of sunlight on the floor, using her incompetent little fingers in some of the practical exercises of everyday living. The directress gave her a stout wooden frame, to which were fastened two soft pieces of gay woolen stuff, one of which was pierced with buttonholes and the other having large bone buttons. Valia worked all one morning before she was able to fit each button in its corresponding buttonhole, but when she did accomplish this, the triumph was a bit of wonder-working in Valia’s control of herself. It started her on the road to physical freedom.

An important physical exercise of Montessori.

Happy in her new accomplishment, she mastered all the other dressing frames; the soft linen with pearl buttons that was like her underlinen, the leather through which one thrust shoe buttons[31] with one’s own button hook, or laced from one eyelet to another, the lacing on cloth like her mother’s Sunday bodice of green velvet, the frames of linen with large and small hooks and eyes, the frame upon which were broad strands of bright-colored ribbon to be tied in a row of smart little bows.

Daily, simple physical exercises such as these; hand and eye co-ordination, exercises in poise, stretching, rest for the limbs and freedom for the spine and torso slowly transformed Valia from a lump of disorganized, putty-like flesh to an erect, graceful, self-controlled little woman.

“What have you done to my Valia?” asked the mother as she waited at the school door for her little one a few months later. “She dresses the young bambino at home and buttons her own shoes. She no longer stumbles all day long but stands well on her feet. She helps me to lay the evening meal and carries a dish of soup, full, to the place of her father. I do not understand it. Did you punish her for climbing and being clumsy?”

“No.” The directress of the Children’s House lays a kind hand on Valia’s curly head as she explains. “We did not punish Valia. We gave[32] her a fence upon which to climb and we let her tumble about on the floor when she was tired, and we helped her to find her feet and her fingers.”

Dr. Montessori tells us that there is a little Valia in every home. The child from one to three and four years of age is in need of definite physical exercises that will tend to the normal development of physiological movements. We ordinarily give the little child’s body slight thought. Then, in the schools, we gather older children into large classes, and by a series of collective gymnastics in which the commands of the teacher check all spontaneity, we try to secure poise and self-control and grace for the child body.

Hand and eye work in connection in exercises of practical life.

Gymnastics for the home will accomplish this result, Dr. Montessori tells us, and these include simple exercises such as one sees in the Children’s Houses. They are planned taking into account the biology of the body of the child from birth to six years of age—the child who has a torso greatly developed in comparison with his lower limbs. They have for their basis these goals:

Helping the child to limb development and control.

Helping the child to proper breathing and articulate speech.

Helping the child to achieving the practical acts of life; dressing, carrying objects without dropping, and the resulting co-ordination of hand and eye.

To bring about this physical development, Dr. Montessori has planned and put into the Children’s Houses in Rome certain very simple physical exercises, so simple as to seem to us almost obvious, but the results in child poise, control, and grace have drawn the attention of the entire world. These exercises include:

Swinging and “chinning” on a play fence, modeled after a real fence or gate.

Climbing and jumping from broad steps, a flight of wooden steps being built for the purpose. Ascending and descending a short flight of circular steps, these steps built for the exercise at slight expense. Climbing up and down a very short ladder. Stepping through the rungs of the ladder as it is laid upon the ground or the floor.

Rhythmic exercises carried out upon a line; walking slowly or fast, softly and heavily, on tiptoe, running, skipping, and dancing in time to music. These exercises may be done by utilizing the long, straight cracks in a hardwood floor, the seams in a carpet, by strewing grain or making a snow line out of doors.

Exercises in practical life, the most important of these being brought about by the use of the dressing frames included in the Montessori didactic materials, and including: buttoning on scarlet flannel, linen, and leather, lacing on cloth and leather, fastening hooks and eyes and patent snaps, and tying bow-knots. Other materials used in these exercises are: brooms and fascinating little scrubbing brushes and white enamel basins with which the children help to make the schoolroom tidy in the morning. And the children are taught to open and close doors and gates softly and gracefully and to greet their friends politely and with courtesy.

Physical training brought about through play with a few toys that stimulate healthful muscular[35] exercises and deep breathing. These toys include rather heavy toy wheelbarrows, balls, hoops, bean bags, and kites.

Breathing exercises. For these, Dr. Montessori recommends the march, in which the little ones sing in time to the rhythmic movement of their feet, an exercise in which deep breathing brings about lung strength. She recommends also the singing circle games of Froebel. She leads the children to practice such simple respiratory exercises as, hands on hips, tongue lying flat in the mouth and the mouth open, to draw the breath in deeply with a quick lowering of the shoulders, after which it is slowly expelled, the shoulders returning slowly to their normal position.

Exercises for practice in enunciation, including careful phonic pronunciation of the sounds of the vowels and consonants and the first syllables of words. This practice in the co-ordination of lips, tongue, and teeth not only helps the child to clear speech but leads to a quicker grasp of reading.

Walking upon a line gives poise and muscular control.

Each of these physical exercises has its basis in child interest. Your toddler instinctively pulls[36] and climbs, stretches, and scrambles about on the floor, longs to dress his own fascinating, wee body, and play into the activities of the home. He loves marked, rhythmic music and longs to hear those jingles and nonsense ditties of childhood’s literature in which syllabic sounds are emphasized and repeat themselves.

“Not commands, but freedom; not teaching, but observation,” Dr. Montessori begs of mothers. So she has taken these instinctive activities of the little child and, using them as a basis, she has built upon them her system of physical training for the baby, a system that needs no bidding, “Do this,” because all children love to climb fences and play with buttons and stretch little limbs on the floor, and keep time to rhythmic music.

The kind of toy Dr. Montessori recommends for physical development.

Every Thursday morning a crowd of thirty or forty eager tourists from all over the world wait with impatience to be admitted to the Montessori school on the Via Giusti, Rome. Silently, led by a white-robed sister, they enter the schoolroom and seat themselves in quiet expectant rows to watch the miracle of Montessori physical freedom. A hush, a tinkle of child laughter, and the babies flock in from the garden. Noiselessly, gracefully,[37] with no rude jostling or crowding—and alone—they greet each visitor with outstretched hands. Then, like a bevy of little men and women, eager to work, eager to achieve, they hasten to the cabinets that hold the didactic materials, to choose their material for the day. Nothing drops, nothing is broken, no child hurts his neighbor in his haste, and they find their places, some stretched out on the floor, some seated at the white tables. When the hour for the midday meal comes, the materials are as carefully put back in their places in the cabinet and the little ones lay the tables for luncheon. To see a child balance a tray that holds five filled tumblers, to see another child bring in a huge bowl of warm soup and serve it with no mishaps, these interest curious sightseers as much as the Roman Colosseum or the Roman baths.

But isn’t, after all, the child who has come, by natural steps, to this control of his mind and body the normal child? Are not our children, whom we feed and dress and lead and fasten into high chairs, the abnormal ones? It is vastly easier to lace a child’s shoes, to hold his hand when he goes up and down steps, to fetch and carry for[38] him, than to teach him this muscular co-ordination, but it is just this careful teaching of the simple things of life that makes the Montessori child a sight for tourists.

“What makes these children so good?” I heard a visitor ask her neighbor one morning as she watched the Via Giusti little ones.

A number of factors contribute to the goodness of the Montessori child, but one of the most important of these is that he “knows himself.” He knows his body, what it can do and what it must not do. This physical freedom leads naturally and surely to freedom of the spirit.

He was so wee a bambino to have absorbed so much brutality in his heart. Not quite three summers and winters old was Otello when his mother pushed him across the threshold of the big, cool, white room of the Trionfale Public School at Rome that houses a Montessori Children’s House. There she left him after a volley of guttural speech that told the little dark-eyed girl directress how uncontrolled and passionate was this baby of Rome, a quaint little “man” in stuff dress and bare legs and torn shoes who looked with stolid wonder into the happy eyes of the other babies.

At first it seemed as if the mother were right. In an awed whisper to Dr. Montessori the girl directress spoke of Otello as “the terrible.” He met love with apparent hate, kindness with malevolence, sociability with taciturn aloofness. Did[40] little Mario with painstaking effort lay a carpet of beautifully tinted color spools in careful order on his table; then Otello swooped down from his watchful corner and with one sweep of his fat hand wrought confusion in the beauty. Did a stone lie, harmless, in the school garden; Otello found it and used it with dire results. Did Valia, the toddler, with much toil fill her small wheelbarrow with a precious load of sticks ready to trundle it across the playground; Otello intervened, overturned the barrow, and gloated over Valia’s tears.

From his first day he showed an amazing inventiveness along lines of disorder. To tear a finished picture that his little girl neighbor had zealously colored, to swoop down upon the heights of the pink tower whose perfect building some other baby had just achieved in a patch of sunlight on the floor and overturn it—these seemed to be Otello’s most joyful triumphs. And always, as he planned some act of disorder, he looked up, expectantly, for the blow, the harsh command with which the misdirected force of childhood is so often met by the brute force of the adult.

But these never came. Instead, he saw a group of sympathetic little ones run softly across the wide spaces of the room to help Mario in rearranging his color spools. There was no thought of him, Otello the law breaker, but only the love of Mario in their hearts. In place of the reproof that he almost longed for, that he might meet it with rebellion, he felt the touch of warm lips on his forehead, and he heard the soft voice of the directress:

“Ah, Otello, that was wrong.”

There was no other word of blame, no command, you must not, for him to meet with his marvelous strength of will and, I shall. He might choose the thing that was wrong—or——

It was one sweet spring morning in Italy that I saw the miracle happen to Otello, a morning when the free breezes from the Roman hills brought heavy odors of grape and orange blooms and the birds sang their freedom outside the windows of the Trionfale Children’s House. Otello sat in a little white chair in front of a little white table, suddenly quiet and thinking. He saw, all about him, other little white chairs and low white tables. If he wished he might choose another chair; no[42] one would insist that he stay in one seat. The brown linen curtains at the windows rustled pleasantly with the perfume-laden wind. If Otello wished he might go out in the playground for a breath of that wind. No one would prevent him. In front of him he saw another large room with a piano and low white cabinets filled with fascinating Montessori materials, and colored rugs for spreading on the stone floor, and many babies, of his own kind, sitting there busily at work. A child might dash over and spoil the work of a dozen children at one attack. Or a child might do a little experimenting himself with these materials that so engrossed the others. Otello chose the latter course, and going to one of the cabinets, he selected one of the solid insets, a long polished wood frame, into which fit ten fascinatingly smooth cylinders of varying diameters. Holding the cylinders by their shining brass knobs, he put them in their proper places in the frame, took them out, put them in again a dozen, a score of times. Unconsciously he was training his sense of touch, but more than this, he was exercising his conscience in a new way. A small cylinder refused to fit in a large hole in the frame; a large cylinder[43] could not be forced, no matter how strenuously he hammered it with his little clenched fist, into a small hole. Before Otello put each cylinder in its proper place, he tested it with a larger or smaller hole.

“Wrong!” he whispered to himself in the first instance; and,

“Right!” he ejaculated when the good, smooth little piece of wood dropped out of sight in its own hole.

After almost three-quarters of an hour of this will training, for the little child who persists in a piece of work and completes it is taking the first steps toward properly directed will, Otello looked up from his work. Mario, his neighbor, bent over the color spools again. From the pocket of Mario’s apron protruded one of the crown jewels of childhood—a big glass marble. Otello had no marble. With all the longing of his heart he had wanted one. Mario bent lower over his color matching and the shining glass sphere, as if it were alive, slipped from his pocket, dropped to the floor, and rolled across to Otello.

With quick stealthiness Otello grasped it in his eager little fingers. It was his marble now; no[44] one had seen him take it; in his little brown palm it held and scintillated a hundred colors. How happy it made him to own it; he would slip it into the hole in his shoe to keep it safe until he reached home! But, even as he made a hurried movement to hide his booty, his prisoned soul burst its cocoon. With one of the rare smiles in his eyes that one sees in the undying children of Raphael, Otello ran over to Mario and dropped the marble in his lap.

Otello had taught himself the right and he had made the right his happy choice.

The old way of helping Otello, of helping your child to right action and self-education, was to command. Yesterday, we said:

“You must do this because I tell you to; this is right because I say that it is.”

Dr. Montessori gives us a new, a better way of educating little children. Before we present her didactic materials to a child, before—even—he leaves his cradle and his mother’s arms, we will give the child his birthright of freedom; physical freedom, mental freedom, moral freedom. The place of the mother in education, Dr. Montessori tells us, is that of the “watcher on the mountain[45] top.” She observes every action of the child, helps him to see the difference between right and wrong, but she leaves him free, that he may train his own will, make his own choice, educate himself.

How can we help our children to the goodness that little Otello has found? What had he missed at home that was supplied to him in the Children’s House?

The root that is denied space by its earth mother to stretch and pull and reach does not grow into a tall, straight tree. The bud, shut off from its birthright of sunshine and moisture, does not unfold into perfect flowering. The child who is choked at home by an artificial environment and chained by the commands of his parents will develop into a crooked, blasted man. Dr. Montessori told me that her first word to American mothers is this:—

“Free your children.”

Every child is born with an unlimited capacity for good. His impulse is to do the good thing, but we so hedge him about with objects which he must not touch and places which he must not explore and inaccuracies of speech which confuse his understanding, that he rebels. With the force of[46] a giant, the baby uses his will to break our will. This is right; he was born as free as air, and we act as his jailers. Presently, his thwarted will finds other outlets, and we are confronted with a little Otello.

We have thought that to “break” a child’s will was the first step toward giving him self-control. We say to a child:

“Don’t be capricious!”

“Don’t tell lies!”

He is capricious because we have so often interfered with his normal child activities, because they made him dirty, perhaps, or caused a litter that we thought disorderly. He lies because we have not explained his world to him, or because he fears us. Seldom is a child capricious or untruthful unless we have made him so.

The Montessori directress at the Trionfale Children’s House, first of all, patiently observed Otello. At the end of a week’s time she knew more about him than his mother did, for she had recorded his height, weight, chest, and cranial development and had discovered that he needed physical exercise to help his mental development. We will watch our children’s bodily growth more carefully than we[47] have in the past if we are to be Montessori mothers.

She never commanded the little fellow whose ears were so deafened with the many commands of his mother that he found it a psychological impossibility to obey. Instead she had faith that his new environment, her careful pointing out of right and wrong, and the ordered activities brought about by the Montessori didactic materials would loose his spirit, which had been like a butterfly stabbed by the pin of a scientist.

So we will be patient with our babies and watch them and wait expectantly for the unfolding of their minds and souls which will surely come if we supply the opportunity.

Dr. Montessori gives us a new word for the home and she blots out an old one.

“Why?” is our new word. We will observe the minutest activity of the home child from its first month to the time when it leaves the home for school, asking ourselves the reason for each activity.

“Don’t!” is our blotted-out word. No activity of a child should be inhibited unless it is morally wrong.

From babyhood to the age of six years almost[48] every free movement, every free thought of the child has a meaning in relation to its bodily and mental growth. If we suffocate children’s activities, we suffocate their lives. The good child is not the quiet, inactive child. The perfect child is not the child who is nearest like man.

The only way to keep a child still is to teach him orderly movement. The only way to keep him from handling our things is to give him educational things of his own to handle.

It is a more fascinating home occupation than any which you ever attempted, this Montessori way of observing your child. He is your own life flower, a bud, now, but with the power of sure, beautiful unfolding into bloom. Your part is to watch the process of this unfolding, and to surround the child plant with light and nourishment and freedom for growth.

You thoughtlessly say, “Don’t sit on the floor and play; you will soil your clothes.”

“Walk faster and keep up with my footsteps or I will not take you out with me to-morrow.”

Dr. Montessori tells us that the limbs of the little child are very short in comparison with his torso and tire quickly from holding up his body[49] weight. If his legs are to grow straight and strong he must follow his own inclination and sit and lie on the floor when he plays; he must not be required to keep up with our longer stride in walking. We were thoughtless when we commanded don’t. Dr. Montessori shows us the why. These actions of the child were wrong only from our standpoint. We have to cleanse soiled clothes; we think that we have no time to walk slowly. But in the Children’s Houses no child is ever required to stay in his small white chair or to keep his work on his low table. He is free to work on the floor in any position which makes him physically comfortable and soft rugs are provided for this purpose. No Montessori child is commanded to stay in line and “keep up” when the piano gives the signal for a march or one of the gay Italian dance steps. Otello and Mario and Piccola, the babies, drop out for a few seconds, seating themselves for a space of rest, and when their fat legs are ready for more muscular exertion, they again join the other children.

But this freedom will make my child fickle, lacking in concentration, you say.

On the contrary, it leads to concentration. The[50] Montessori-trained child who has never been prevented from doing a thing unless it was wrong and who has been allowed to carry on any activity which it chooses; free play with outdoor toys, the Montessori physical exercises, sense-training, drawing, suddenly arrives, at five or six years at a most unusual amount of concentration. From a free choice of occupations that lead to the exercise of the muscles and the senses, the minds of these little children order themselves, and the children are able to concentrate on one line of thought for long periods.

In the Children’s House of one of the Model Tenements in Rome, I saw a little girl come quietly in at nine o’clock, button on her apron, and seat herself with a book. She read, happily, for three-quarters of an hour, hardly lifting her eyes from the pages, although twenty-five other little ones were carrying on almost as many different occupations all about her. At the end of this time, she closed her book, crossed to the blackboard, looked out of the window a moment, and wrote in a clear hand the following childish idyl to the day:

“The sun shines,” it began. “I smell the orange flowers and the sky is blue and I hear birds[51] singing. I am happy because it is a pleasant day.”

Do we find such concentration in our children whom we teach according to rule and in masses? We have thought that to educate was to formulate a great many rules and make our little ones follow them, but our new Montessori ideal is a very different matter—that of leaving Life free to develop and to unfold.

The American child has the strongest will, his gift from a vital heredity, of any child in the world. His father and his mother have, also, this splendidly forceful inherited will. Parent and child tilt and bout in a daily fight, and if the parent comes out triumphant and succeeds in breaking the child’s will there is a deadly wrong done. That is why our reform schools and prisons are so full of strong wills, beyond bending.

We must let our little ones blaze their own trails, provided, of course, that they are trails which lead in the right direction. We must, also, let them make their own decisions, and if occasionally they prove to have been wrong, the experience will have helped them to decide wisely the next time. We will, also, put into their hands the self-corrective didactic apparatus of Montessori,[52] which has a distinct ethical value in the training of the human will.

Education to be vivid and permanent in the child’s life should be worked out along lines of experience. To say to a child, “Don’t do that; it isn’t right,” is to make a very inadequate appeal to one, only, of his senses, that of hearing. To put into the child’s hands the blocks of the Montessori tower so carefully graded in dimension that it takes exquisite differentiation to pile them is to give him a chance to learn through experience the difference between right and wrong by means of three senses. He hears a possible direction as to their use, he touches them, he sees the perfectly completed tower. In like manner the broad and long stair, the solid and geometric insets, all contribute their quota to the sum of the child’s perfectly directed will control.

The average home is full of mediums for helping a little child to develop along lines of willed control. To concentrate upon a bit of constructive play until it is finished, to learn orderliness in putting away playthings, or to do some simple home duty that will be carried over from day to day, all are important willed activities. To do[53] whatever is in hand, building or drawing or picking up toys, or bathing or caring for a doll or a pet, or helping mother as well as possible, is, also, very vital will-training.

Dr. Montessori helps us to a hopeful outlook on the subject of child will. Our Otellos are not, after all, terrible. The child who is most difficult to manage is, with Montessori training, the child who turns out to be best able to manage himself.

When Bruno was a little fellow, his mother and father were killed in the Messina earthquake.

Because he was one of so many left-behind babies, he was quite neglected, and he grew up to four years as a weed grows. Sometimes one madre of the tenement mothered him, sometimes not. At times he was fed, at other times he starved. Because of the great fear that came to him with the blinding smoke and the twisting red river of molten lava and the death cry of his girl mother that day of the earthquake, Bruno’s mind seemed a bit dulled. He was often confused by the commands of people who tried to take care of him and so could not obey. Then they would strike him. And he heard very vile language spoken and he saw very evil things done during his babyhood in the tenement.

When Bruno wandered across the threshold of the Via Giusti Children’s House in Rome, he[55] seemed like a little alien among the other happy little ones who were so carefully watched over, so gently led. For days he sat in silence, his great, frightened blue eyes watching to help him dodge the blow that he expected but never felt; his lips ready to imitate the vile speech that he had known before, but which he never heard here. His timid fingers fumbled with the big pink and blue letters that the other children used in making long sentences on the floor; they tried to button, to lace, to match colors, but not very effectually. It was as if the great fear of his babyhood had shadowed his whole mental life and left him powerless.

One morning Bruno’s dulled blue eyes glimpsed an unusual stir among the children. A new little one had come and, full of disorderly impulses, had snatched at the varicolored carpet of carefully arranged color spools Piccola had placed on her table, scattering them to the floor. Red, green, orange, yellow, Piccola’s painstaking work of an hour lay in a great, colored, mixed-up heap. Piccola’s eyes, still pools that reflected all the hazel tints of fall woods, grew blurred with tears. She dropped her curly head in her arms and sobbed, big, gulping sobs that wouldn’t stop, that strangled[56] her. Bruno, watching her, found his muscles. He ran to her, putting one kind little arm around her waist, and with the other drew her head down to the shoulder of his little ragged blue blouse and smoothed her hair, talking sweet, liquid nonsense all the time that made Piccola’s sobs grow less and less, and comforted her. When she smiled and drew away to watch the group of children who had hurried to pick up her colors for her, Bruno slipped back to his corner and the old, dull look settled back in his face.

“The little man has the conscience sense. He shall have a chance to use it,” thought the Montessori directress who had been watching the scene.

And because she wanted his soul to grow strong, even if his timid fingers couldn’t, she often stopped by Bruno’s chair to hold his hand, kindly, for a minute in hers, or just bent over him, smiling straight down into his face.

“No one will hurt this little man of ours. He loves us and we love him,” she assured Bruno over and over, until one day her patience reaped the prize of Bruno’s answering smile and she felt his two hungry little arms clasping her.

She strengthened his beginning friendship with[57] Piccola, the color-loving, reckless, daring little maid, whom all the children loved to love and loved to fight. When Piccola brought an unusual treat in her luncheon basket, a leaf-wrapped packet of dried grapes or two luscious figs instead of one, the directress suggested that she share with Bruno, who had no one to tuck a surprise in his basket. As the two child faces drew close above the feast and the little hands fluttered together over this friendly breaking of bread, Bruno’s eyes sparkled. He was reading his first lines in the primer of love; he was finding his sight. And in return Bruno helped Piccola to rake leaves in the garden, he unrolled and carefully spread upon the floor the rug upon which Piccola wished to curl herself and sort letters; he hastened to add his strength to hers when the drawer that held the letters stuck; he fought Piccola’s street battles for her.

Soon Bruno’s loving busy-ness so increased that he found things to do almost every second of his happy days in the Children’s House. No longer the little cowering, cringing, inactive child of a few weeks past, he was an alert little man whom I instantly watched, because his activity was so unusual. When the line of children, two by two[58] and clasping hands, in their pretty custom of welcoming visitors to the Via Giusti Children’s House, tumbled in each morning, Bruno always headed the line. He held by the hand the smallest, newest, or the most timid child, dragging it in his eagerness to teach it to shake hands and say good-day. He would “hold up” the line because he had so much to say in his welcome to the strangers who had come to spend the morning with the little ones.

“See our Signorina; is she not kind?

“This is our room; do you like it?

“There is Margherita; she writes!

“This is Piccola, who reads!”

In breathless sentences, Bruno’s heart interest worded itself. Then, as the others settled themselves for the day’s work, Bruno began his day of service. He was the Loving One, the Helping One, the Comforting One of the Via Giusti Children’s House. Was any child left without a glass of water at the luncheon hour, Bruno fetched it. Did the little girl waitress for the day forget to fill a soup plate from her tureen, Bruno reminded her. If the three-year-old started home with his cloak unbuttoned, Bruno, feeling in his[59] tender little heart the chill wind of the Roman hills, buttoned the cloak for the baby. If a toddler tumbled down, Bruno picked it up and examined it for bumps, and started it safely on its way again. He fetched and carried, watched for chances to help, to champion the weak, to wipe away anybody’s tears with the hem of his apron.

The seat he most often chose was under a cast of the Madonna. Sometimes he sat quiet for long spaces, looking at it. “Bruno calls the Madonna his madre,” whispered Piccola one day.

“Who is that big, homely child?” asked a visitor, pointing to Bruno putting fresh water in a bowl of roses that stood under the cast. “Isn’t he older than the other children?”

“Older—yes, in spirit,” answered the far-seeing directress. “He is our little Christ-child.”

So he is our little Christ-child. Wherever there is a child in a home, Dr. Montessori tells us, there Christ is. She discovers for us a new sense, the “conscience sense,” only waiting for an opportunity to exercise itself and, in the exercising, unfold and bloom and ripen into the fruits of the spirit. If being an orphan and hungry and beaten[60] and knowing vile things couldn’t hurt the soul of Bruno, think of the possibility of Christ in your baby.

Children grow, mentally, through the right exercise of the senses. To see and to be able to distinguish between beautiful colors and beautiful forms; to discriminate between sounds that are discordant and sounds that are harmonious; to know rough things and smooth things, round things and square things, velvet things and linen things, by touching them with the finger tips, this we know is a starting point on the road of the three R’s of everyday education. Dr. Montessori guides us a lap farther in the new education. She sees, born with every child, eyes of the spirit and slender, groping fingers of the soul that look and reach for the good. To help a child to use his spirit eyes and his soul fingers means to give him a chance to exercise his conscience. It is a new sort of sense-training that means his finding the three R’s of the life of the spirit: faith, hope, and charity.

How shall we help a child to exercise and train his conscience sense?

Dr. Montessori tells us that if we but watch a[61] little child’s free, spontaneous use of his soul fingers, his daily loves and hopes and faith, these will shine for us as a Bethlehem star-path leading us to the manger-throne of a King-in-the-making. As we are turning a child’s tendency to handle into mind-training, we will turn his manifestations of inner sensibility into morality.

It is quite ineffectual to say to a child:

“You must love your neighbor.”

Of course he will try to do the thing that we ask of him because he is a very kind little person, ready to put up with the inconsistencies of his elders and willing to try to obey; but it will be a makeshift sort of love, not free and a flowering of the child’s own heart, but built upon what we tell him about love. This makes of children little puppets.

Dr. Montessori says: “Watch how children love and what they love.”

You know how your child loves—with the thoughtless abandon of pure passion. That he interferes with your important occupation, crumples your immaculateness, has a soiled face and sticky fingers when he kisses you, do not enter into his thoughts. That anything should interfere with[62] his caresses would wound his heart. If you were disfigured or maimed, he would still vision you as the beautiful mother whom baby eyes see only with the eyes of adoration.

Is this a love that we can teach?

You know what your child loves. There was the ugly yellow puppy with muddy feet that stained your new rug; don’t you remember how the Little Chap sobbed so long, and then woke up in the night crying, the day you sent away the yellow puppy? He loved, too, the dirty rag doll that you burned and the broken toy that you threw away, and that little street gamin of a newsboy who stands at the corner in all kinds of weather. He doesn’t love ceremony and money and the opinions of other people as we do. The Little Chap goes out into the highways and byways for his stuff of love. And he doesn’t care if the thing he loves is ugly, or old, or halt, or lame, because he sees, with his soul eyes, behind the veil of appearances to the real of it.

Your child is born with faith and hope, too. If you tell him that the moon is made of green cheese and that a stork dropped him down the chimney, he believes you, and when he grows up[63] and catches you in the lies, he has one less peg in his moral inner room to pin his faith in the divine to. If you tell him that you will take him to the circus, and then let your bridge party interfere with that promise, the Little Chap is going to be less hopeful that God will keep His promises, for you stand for the divine in the Little Chap’s beginnings of spirituality.

Dr. Montessori says that we often crush the child’s conscience sense by not giving him an opportunity to exercise it as he is led to, instinctively. We must let our children, in their baby days, love as they wish and what they wish. We must be quite careful to give them true conceptions of the strange world in which they find themselves, and we must make only good promises to children and use much vigilance in keeping those promises.

Dr. Montessori sets another guidepost for us in the star-path by which our children will travel across the desert of unbelief to the manger where God, incarnate, lies. She tells us that, as the Ten Commandments were a very simple set of laws for the Israelites, and John, in his preaching of simplicity, paved the way for Christ, so the first religious[64] teaching of the little child should have this same quality of directness.

The child’s first religious training will consist in a discrimination between good and evil.

“It was good of you to share your sweets with sister. When you ate your chocolate, alone, yesterday, I was sorry, because it was selfish.”

“It was thoughtful of you to fetch grandfather’s cane for him. Some little boys would not have been so kind.”

“You must not scream and kick when you are angry. It is wrong!”

We might say in contrast; we do, ordinarily, say:

“You must share because I wish you to.”

“You must be kind because the world likes gentlemen.”

“You mustn’t scream and kick, because you give me a headache and mar my furniture.”

Such commands are quite ineffectual, because they call the child’s attention to us and not to his own acts. But patiently and effectually to see that the Little Chap knows the difference between good and evil and practices good instead of evil—this gives him a chance to train and[65] strengthen his conscience sense and forms the beginnings of his moral life.

“But how shall I give my child an idea of God?” thousands of thinking parents object.

It isn’t necessary to give the idea of God to your child. Dr. Montessori tells us that every child has it.

We think that we must do so much teaching in order to educate the little child’s mind, or his soul. In fact we need to do less teaching than watching, less pruning than watering. After observing our little ones’ spontaneous manifestations of love and giving these a chance to increase, and meeting them with encouragement after conscientiously pointing out to them the good and the evil of life and insisting that they choose the good and reject the evil—we discover a miracle. God comes to the little ones.

Bruno, starved in his mind and starved in his heart, and never having heard of things of the spirit except in terms of the vilest blasphemy, found God as naturally as he would find the first gold blossom of the broom braving winter’s frosts on the Appian Way.

Our own Helen Keller, deaf and dumb and blind,[66] knew God before anything that her teacher could tell her about Him had pierced the dark wall of her sleeping senses.

Dr. Montessori asks us to prepare the way for this miracle in our homes. She says that she would like to suggest to mothers a new beatitude, “Blessed are those who feel;” and we add,

For they find God.

Your little one, Mario, might have been, big eyes instantly glancing a bit of color, something that moved, something that could be handled or broken. All his four years he had been fighting his mother, his home, the world—a one-sided fight, too, for everybody and everything always triumphed over him in the end. He was so little and so ineffectual to do battle.

And the times when he had been punished for breaking his mother’s cherished plates with the pattern of raised roses—plump and red—for clutching in loving, chubby, grimy hands the soft silk window curtains or the bright velvet table-cover could not be counted. Yet Mario was cheerful and uncowed and continued the struggle, the impulse for which had been born with him, to use his fingers in learning about the world of things.

To check this impulse was the object of everyone[68] who had anything to do with little Mario. There was his grandmother in a wonderful silk headdress and a yellow wool shawl, fringed; she would not let Mario clutch the cap and then feel of the shawl, as his fingers itched to. There was the old fruit man at the corner near Mario’s house; he shook a stick at children who handled his round and square measures, his fruits, and vegetables of so many different shapes. There was always his madre, who pursued Mario from waking to sleeping time, interfering with his activities.

“Mario, don’t run your fingers along the window ledge; don’t handle the door latch. You will soil them. You must not play with copper bowls and pots; they are for cooking, not for little boys.”

As the warfare continued, Mario grew bolder. To be stopped when one is playing with a fruit measure or a door latch or a bright, red copper bowl with no malicious designs upon these but only to satisfy a sense of hunger for knowledge of form, hurt his spirit.

“I will,” he announced one day, when his grandmother tried to rescue her cap from his deft fingering,[69] and he pulled off one of the long, silken streamers.

“I will not,” he further asserted when his mother wished the copper pot to cook her beans, and when she tried to take it from him forcibly, Mario stamped and shrieked and struck his madre.

The habit of saying “I will” or “I won’t” in situations that demand the will to decide, “I won’t” or “I will” is an easy habit for a little child to form and a most dangerous one, morally. It is seldom a self-formed but a parent-stimulated habit. When his mother put Mario, for reformation and “to get rid of him,” in The House of the Children at the Trionfale School in Rome, it was with the assurance:

“He’s a bad little boy. He never does what he ought to; he’s always in mischief.”

“What should be a little child’s ‘oughts’ the first years of life? Isn’t what we call getting into mischief, perhaps, the big business of childhood?” we asked ourselves as we watched Mario in his Montessori development. So, at least, Mario’s teacher decided.

“Go as you please, do as you wish, play with whatever you like—only be careful not to hurt[70] the work or the body of any other little one,” were the words that turned Mario’s struggles to educate himself into a joy instead of a fight.

Sitting in the light of the Roman sunshine and the smiles of the other children of the Children’s House, Mario began to do the thing he was born for in babyhood—he began to see with his fingers.

Replacing the solid insets by the sense of touch alone.

Building the tower and the broad stair.