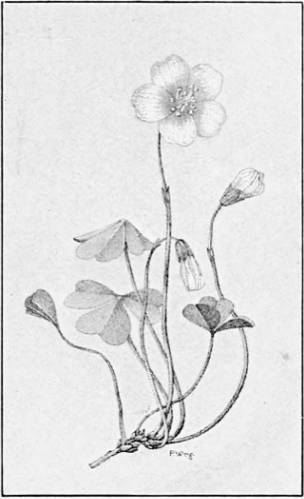

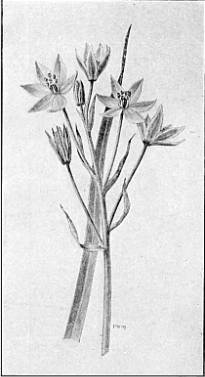

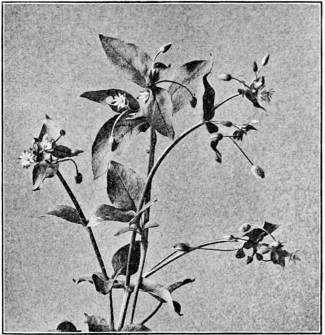

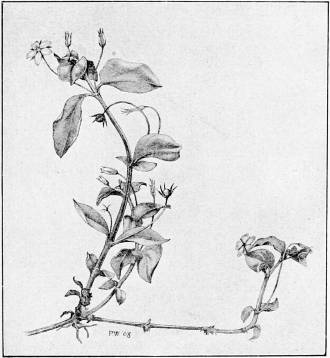

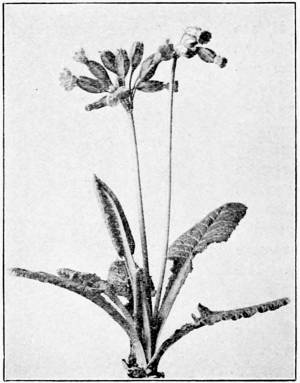

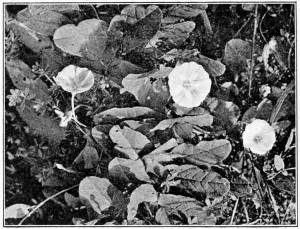

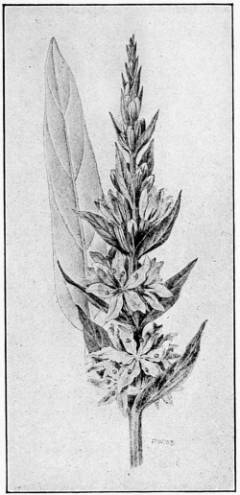

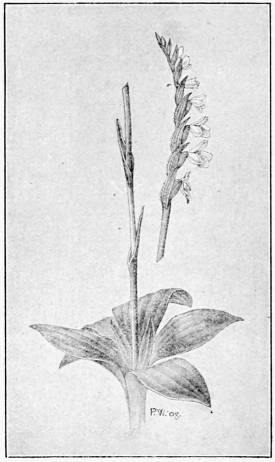

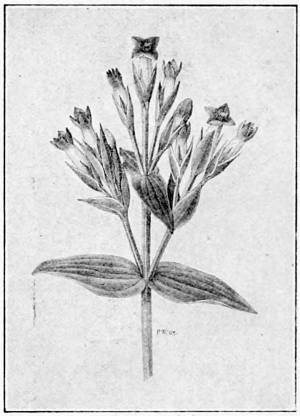

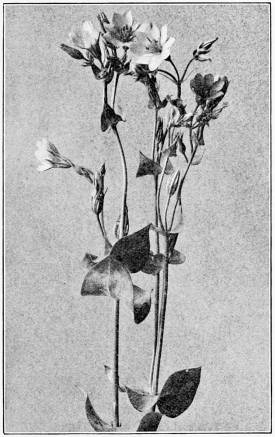

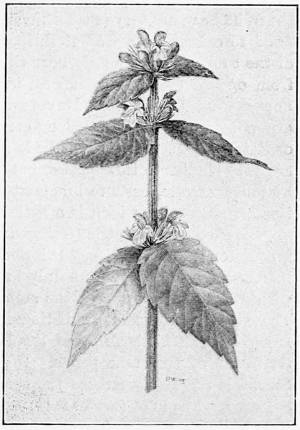

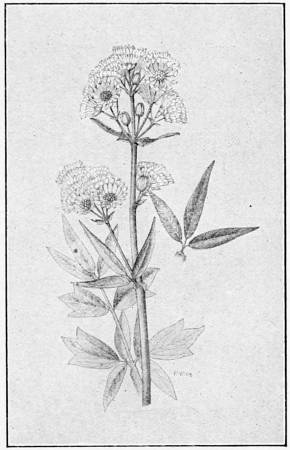

Plate I.

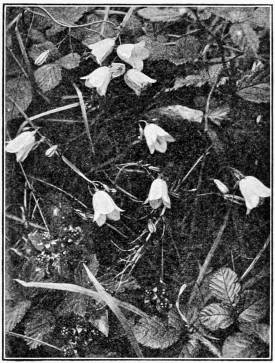

SPRING FLOWERS OF THE WOODS.

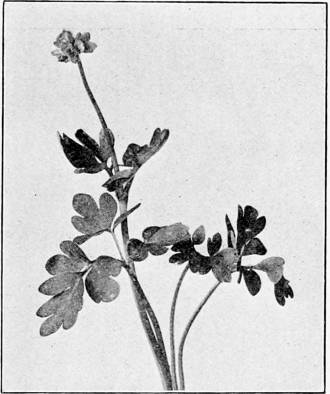

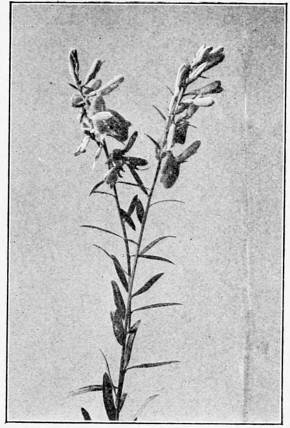

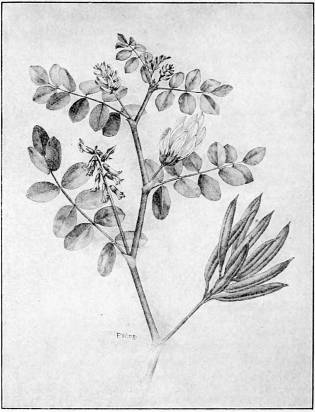

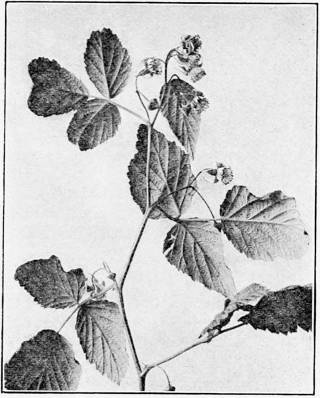

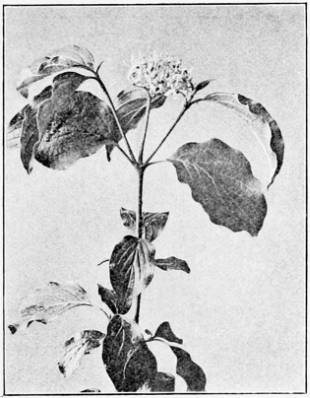

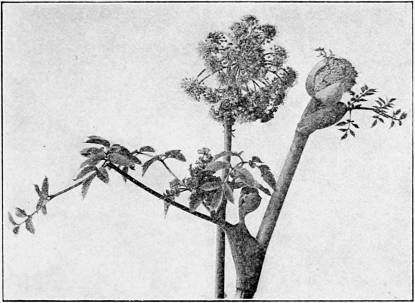

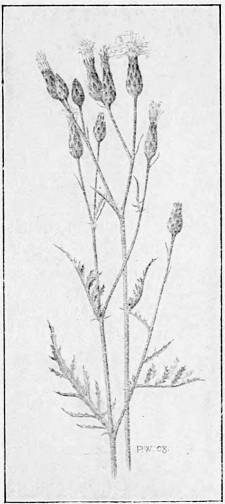

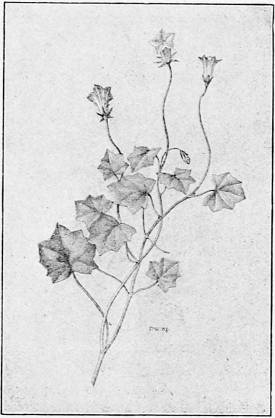

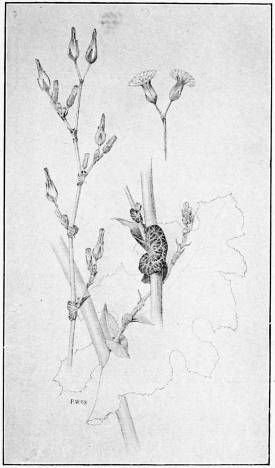

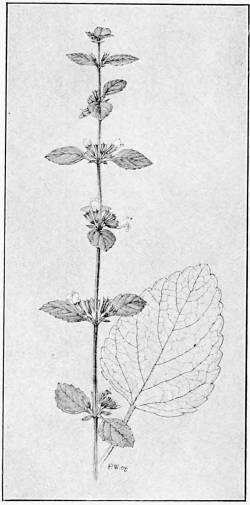

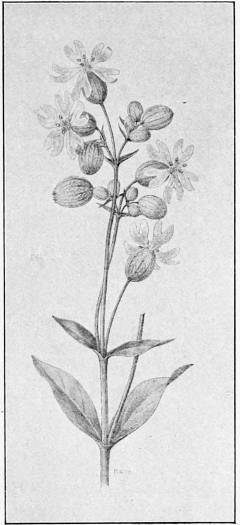

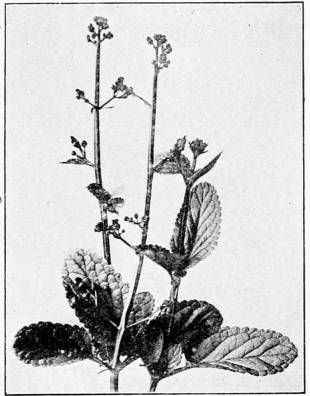

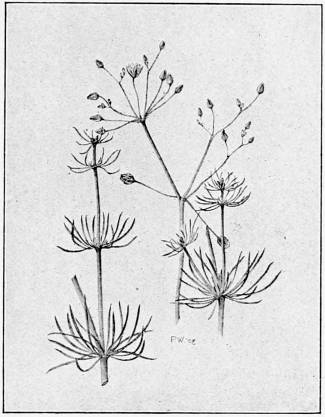

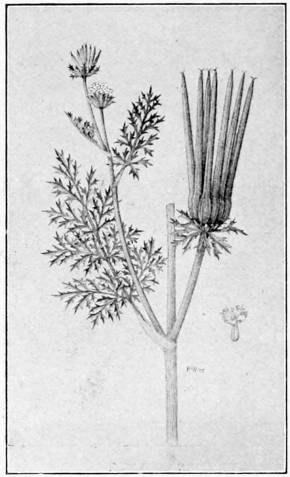

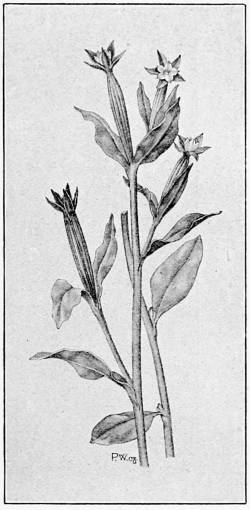

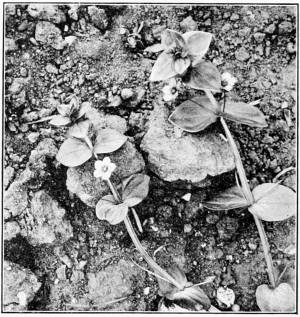

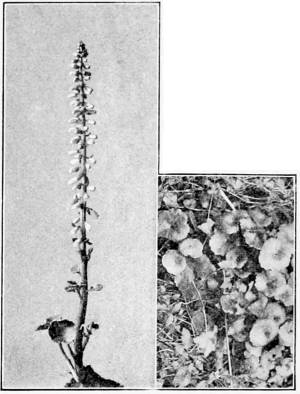

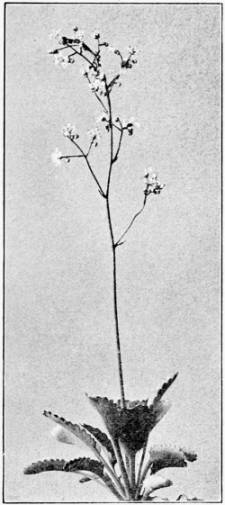

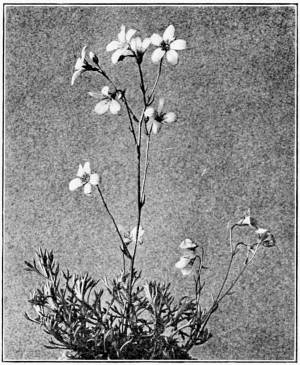

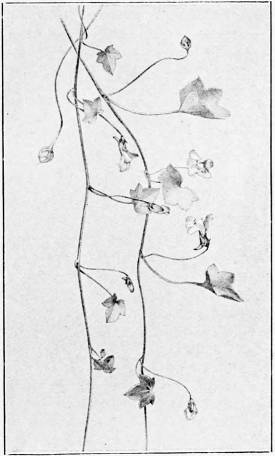

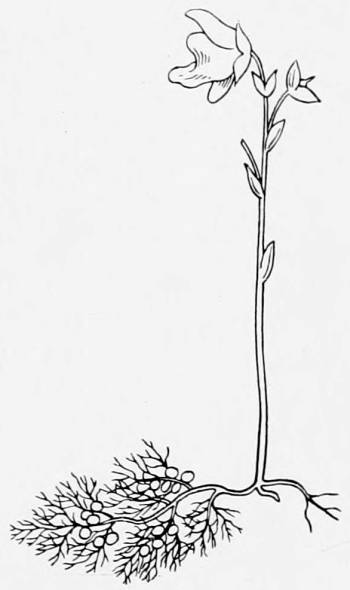

- 1. Green Hellebore.

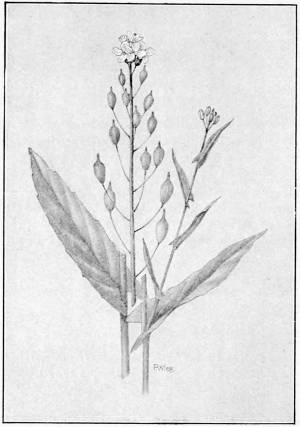

- 2. Plantain-leaved Leopard's-bane.

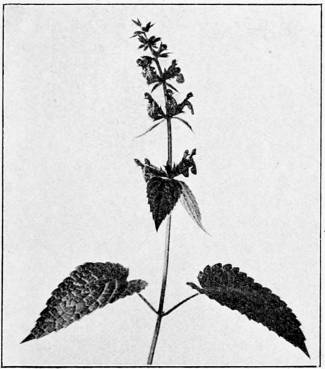

- 3. Lady's Slipper.

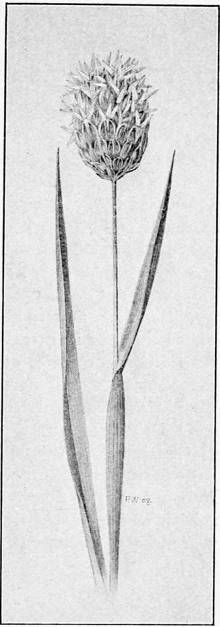

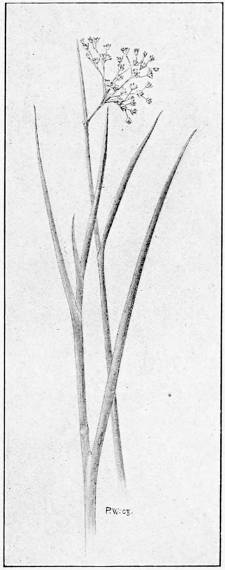

- 4. Sand Garlic.

- 5. Wild Hyacinth.

- 6. Wood Melic Grass.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Field and Woodland Plants

Author: William S. Furneaux

Release Date: May 11, 2013 [eBook #42696]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FIELD AND WOODLAND PLANTS***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/fieldwoodlandpla00furn |

THE OUTDOOR WORLD; or, the Young Collector's Handbook. By W. S. Furneaux. With 18 Plates (16 of which are coloured), and 549 Illustrations in the Text. Crown 8 vo. gilt edges, 6s. net.

BUTTERFLIES AND MOTHS (British). By W. S. Furneaux. With 12 coloured Plates and 241 Illustrations in the Text. Crown 8 vo. gilt edges, 6s. net.

LIFE IN PONDS AND STREAMS. By W. S. Furneaux. With 8 coloured Plates and 331 Illustrations in the Text. Crown 8 vo. gilt edges, 6s. net.

FIELD AND WOODLAND PLANTS. By W. S. Furneaux. With 8 Coloured Plates and numerous Illustrations from Drawings by Patten Wilson and from Photographs. Crown 8 vo. gilt edges, 6s. net.

THE SEA SHORE. By W. S. Furneaux. With 8 Plates in colour and over 300 Illustrations in the Text. Crown 8 vo. gilt edges, 6s. net.

BRITISH BIRDS. By W.H. Hudson. With a Chapter on Structure and Classification by Frank E. Beddard, F.R.S. With 16 Plates (8 of which are coloured), and over 100 Illustrations in the Text. Crown 8 vo. gilt edges, 6s. net.

COUNTRY PASTIMES FOR BOYS. By P. Anderson Graham. With 252 Illustrations from Drawings and Photographs. Crown 8 vo. gilt edges, 3s. net.

LONGMANS, GREEN, & CO. 39 Paternoster Row, London, New York, Bombay, and Calcutta.

Plate I.

SPRING FLOWERS OF THE WOODS.

FIELD

AND

WOODLAND PLANTS

BY

W. S. FURNEAUX

AUTHOR OF

'THE OUTDOOR WORLD' 'BRITISH BUTTERFLIES AND MOTHS'

'LIFE IN PONDS AND STREAMS' 'THE SEA SHORE' ETC.

WITH EIGHT PLATES IN COLOUR, AND NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS BY PATTEN WILSON, AND PHOTOGRAPHS FROM NATURE BY THE AUTHOR

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON

NEW YORK, BOMBAY, AND CALCUTTA

1909

All rights reserved

This additional volume to the young naturalist's 'Outdoor World Series' is an attempt to provide a guide to the study of our wild plants, shrubs and trees—a guide which, though comparatively free from technical terms and expressions, shall yet be strictly correct and scientific.

The leading feature of the book is the arrangement of the plants and trees according to their seasons, habitats and habits; an arrangement which will undoubtedly be of the greatest assistance to the lover of wild flowers during his work in the field, and also while examining and identifying his gathered specimens at home.

A large portion of the space has necessarily been allotted to the descriptions of plants, several hundreds of which have been included, and a large proportion of these illustrated; but not a little has been devoted to an attempt to create an interest in some of those wonderful habits which lead us to look upon plants as living beings with attractions even more engrossing than their beautiful forms and colours.

It has been thought advisable to give but little attention to aquatic plants and to the flowers which are to be found only on the coast, these having been previously included in former volumes of this series dealing, respectively, with pond life and the sea shore.

The thanks of the author are due to his friend, G. Du Heaume, Esq., for his valuable assistance in collecting many of the flowers required for description and illustration.

W. S. F.

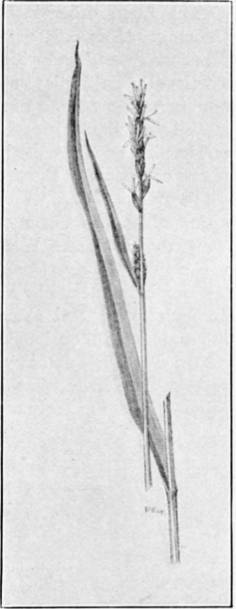

| I. Spring Flowers of the Woods | Frontispiece |

| 1. Green Hellebore | |

| 2. Plantain-leaved Leopard's-Bane | |

| 3. Lady's Slipper | |

| 4. Sand Garlic | |

| 5. Wild Hyacinth | |

| 6. Wood Melic Grass | |

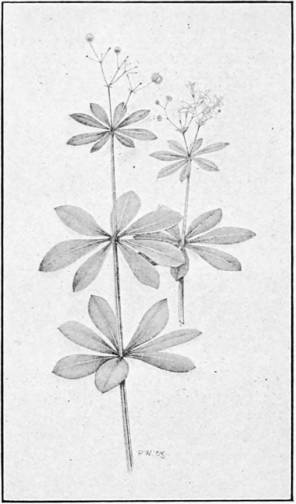

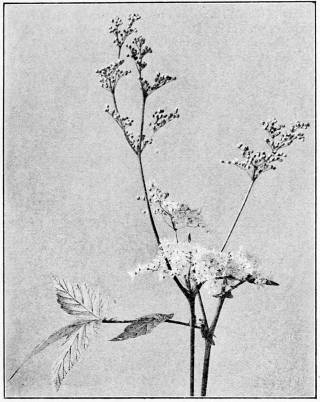

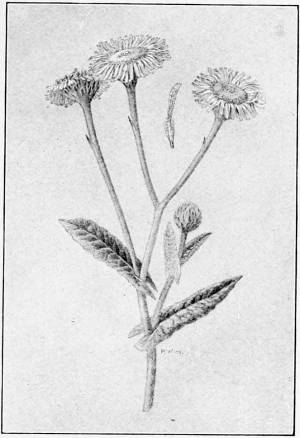

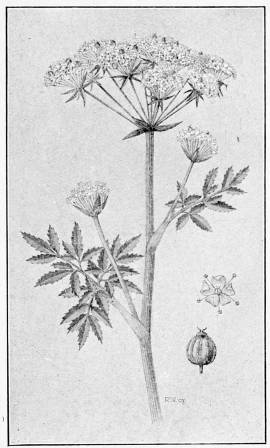

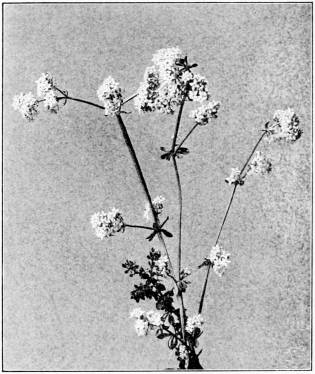

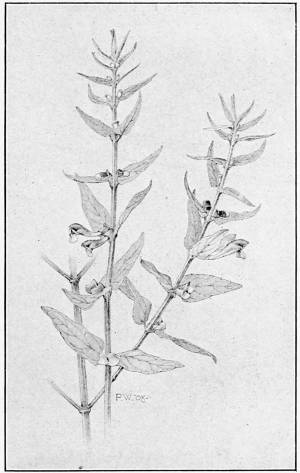

| II. Flowers of the Woods | To face p. 130 |

| 1. Great Valerian | |

| 2. Foxglove | |

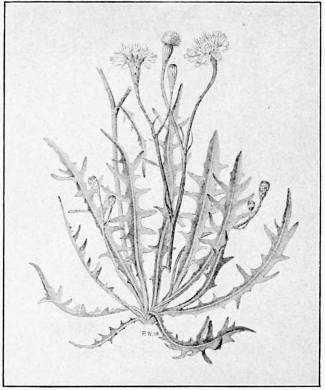

| 3. Succory-leaved Hawk's-beard | |

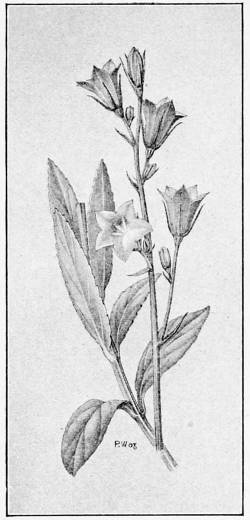

| 4. Nettle-leaved Bell-flower | |

| 5. Broad-leaved Helleborine | |

| 6. Hairy Brome-grass | |

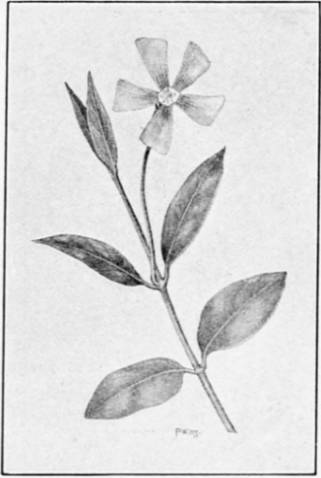

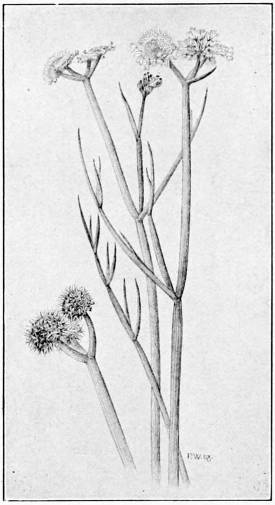

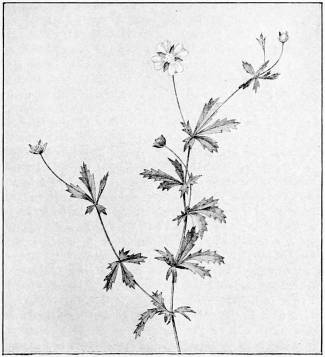

| III. Flowers of the Wayside | To face p. 150 |

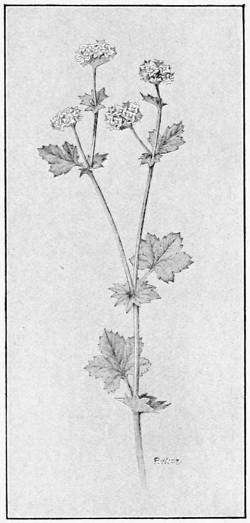

| 1. Round-leaved Crane's-bill | |

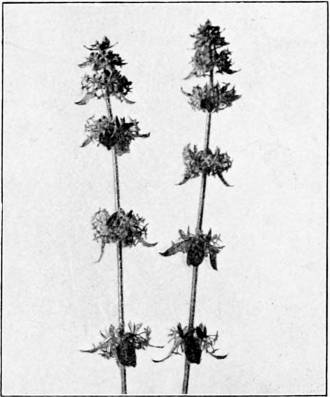

| 2. Black Horehound | |

| 3. Evergreen Alkanet | |

| 4. Bristly Ox-tongue | |

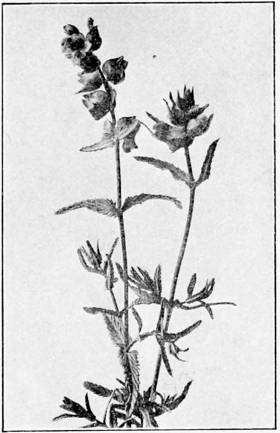

| 5. Red Bartsia | |

| 6. Annual Meadow Grass | |

| 7. Hemlock Stork's-bill | |

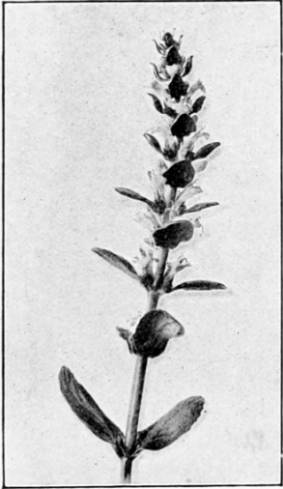

| IV. Flowers of the Field | To face p. 210 |

| 1. Rough Cock's-foot Grass | |

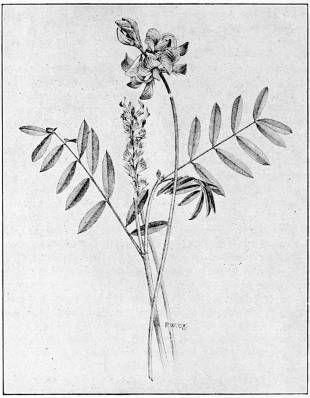

| 2. Lucerne | |

| 3. Crimson Clover | |

| 4. Blue-Bottle | |

| 5. Common Vetch | |

| 6. Meadow Clary | |

| V. Flowers of Bogs and Marshes | To face p. 236 |

| 1. Marsh Gentian | |

| 2. Marsh Marigold | |

| 3. Marsh Orchis | |

| 4. Marsh Mallow | |

| 5. Marsh Vetchling | |

| 6. Marsh St. John's-wort | |

| 7. Bog Pimpernel | |

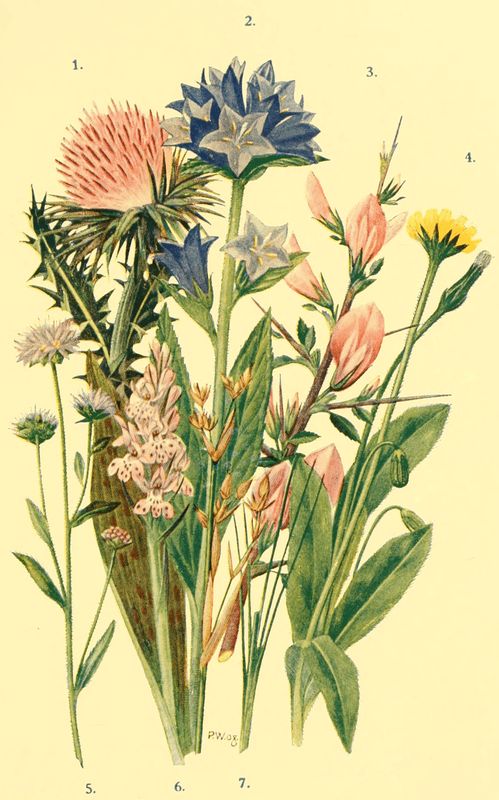

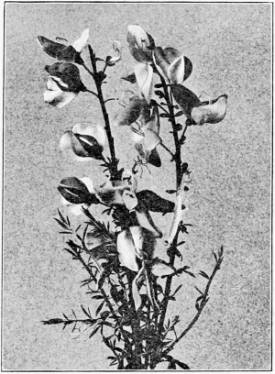

| VI. Flowers of Down, Heath, and Moor | To face p. 256 |

| 1. Musk Thistle | |

| 2. Clustered Bell-flower | |

| 3. Spiny Rest Harrow | |

| 4. Hairy Hawkbit | |

| 5. Sheep's-bit | |

| 6. Spotted Orchis | |

| 7. Heath Rush | |

| VII. Flowers of the Corn-field | To face p. 280 |

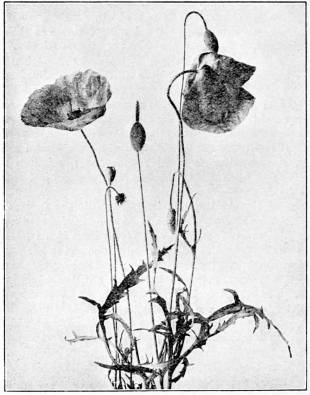

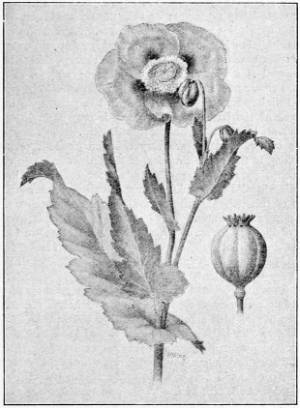

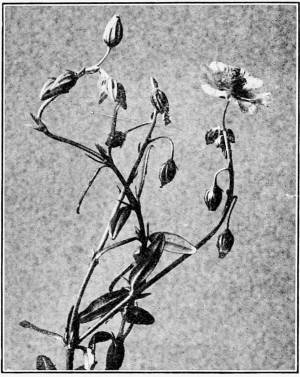

| 1. Long Smooth-headed Poppy | |

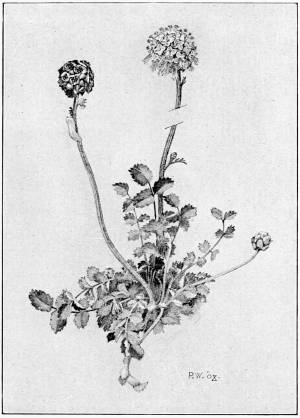

| 2. Field Scabious | |

| 3. Corn Cockle | |

| 4. Corn Marigold | |

| 5. Flax | |

| 6. Corn Pheasant's-eye | |

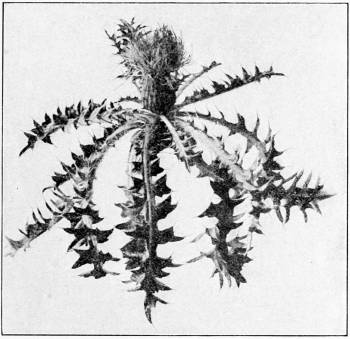

| VIII. Flowers of Chalky Soils | To face p. 296 |

| 1. Red Valerian | |

| 2. Narrow-leaved Flax | |

| 3. Tufted Horse-shoe Vetch | |

| 4. Spiked Speedwell | |

| 5. Pasque Flower | |

| 6. Bee Orchis | |

| 7. Yellow Oat Grass | |

Erratum.—On Plate VI, for 'Spring Rest Harrow' read 'Spiny Rest Harrow.'

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| General Characters of Plants | |

| Forms of Roots | 2 |

| Running underground stem of Solomon's Seal | 4 |

| Arrangement of Leaves | 5 |

| Leaf of Pansy with two large Stipules | 5 |

| Margins of Leaves | 6 |

| Various Forms of Simple Leaves | 7 |

| Forms of Compound Leaves | 7 |

| Forms of Inflorescence | 8 |

| Longitudinal Section through the flower of the Buttercup | 10 |

| Inferior and Superior Ovary | 11 |

| Unisexual Flowers of the Nettle | 11 |

| Dehiscent Fruits | 12 |

| The Pollination and Fertilisation of Flowers | |

| Pollen Cells throwing out their Tubes | 25 |

| Climbing Plants | |

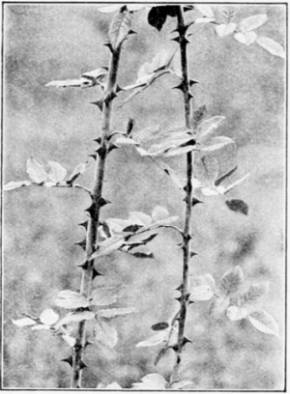

| Prickles of the Wild Rose | 31 |

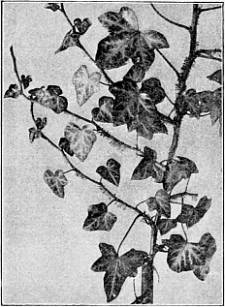

| Ivy, showing the Rootlets or Suckers | 32 |

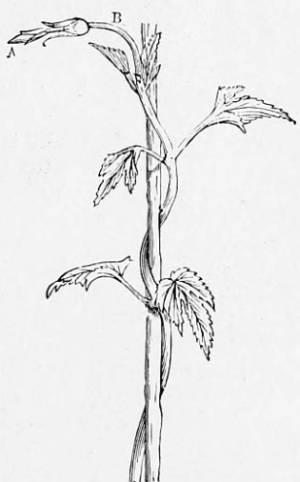

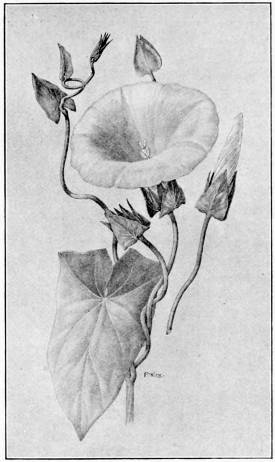

| Stem of the Bindweed, twining to the left | 34 |

| Stem of the Hop, twining to the right | 35 |

| Early Spring | |

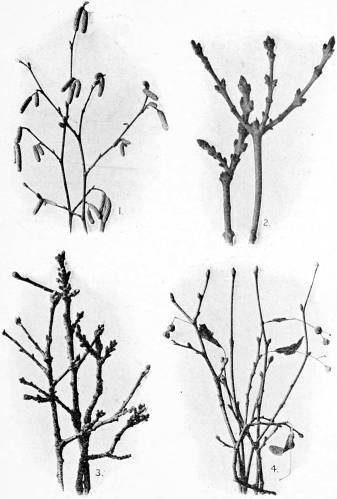

| Trees in Winter or Early Spring | |

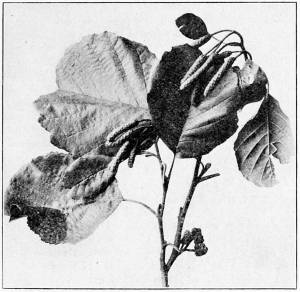

| 1. Hazel; 2. Ash; 3. Oak; 4. Lime | 41 |

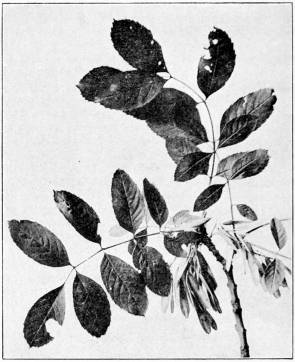

| 5. Birch; 6. Poplar; 7. Beech; 8. Alder | 43 |

| Twig of Lime in Spring, showing the Deciduous, Scaly Stipules | 45 |

| Seedling of the Beech | 46 |

| Woods and Thickets in Spring | |

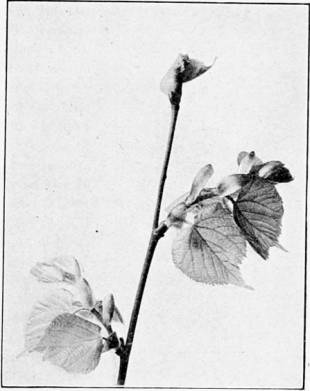

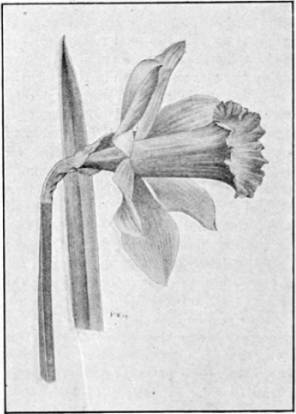

| The Daffodil | 48 |

| The Wood Anemone | 49 |

| The Goldilocks | 50 |

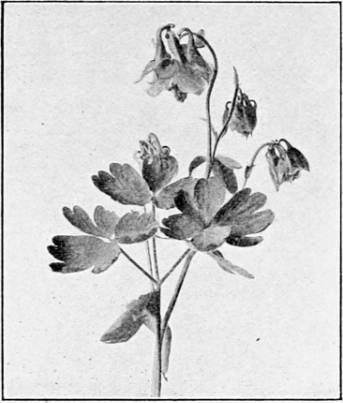

| The Wild Columbine | 51 |

| The Dog Violet | 52 |

| The Wood Sorrel | 53 |

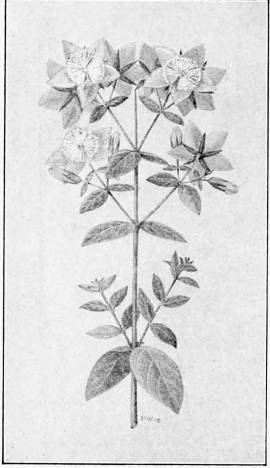

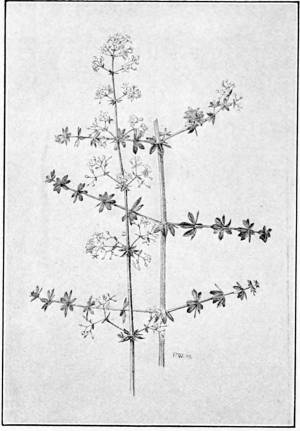

| The Sweet Woodruff | 54 |

| The Lesser Periwinkle | 55 |

| The Bugle | 56 |

| The Broad-leaved Garlic | 57 |

| The Star of Bethlehem | 58 |

| The Hairy Sedge | 59 |

| Spring-flowering Trees and Shrubs | |

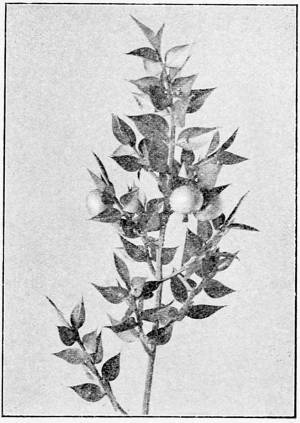

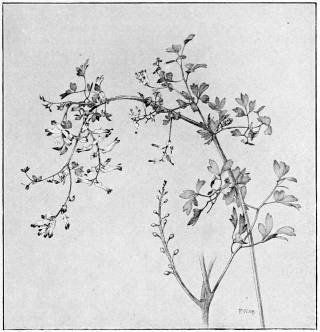

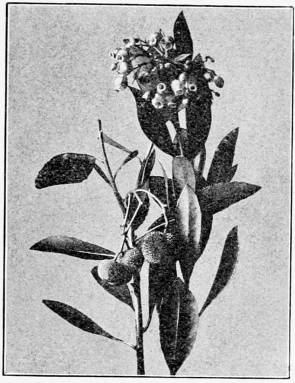

| The Barberry | 62 |

| The Spindle Tree | 63 |

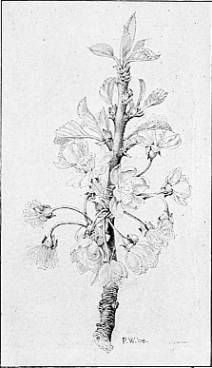

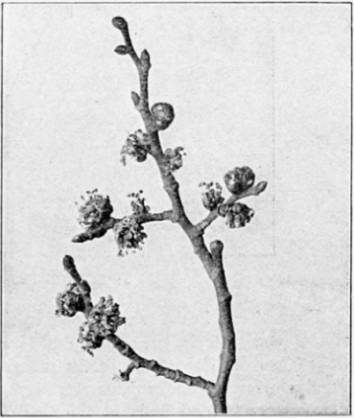

| The Wild Cherry | 65 |

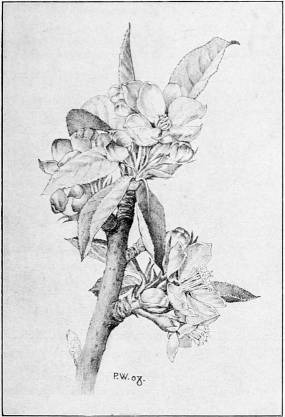

| The Crab Apple | 67 |

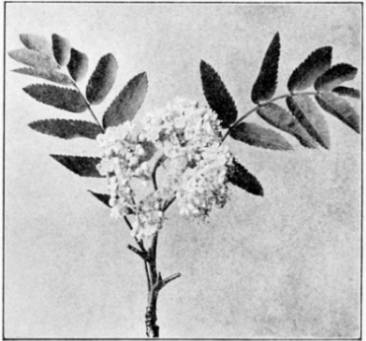

| The Mountain Ash | 68 |

| The Spurge Laurel | 70 |

| The Elm in Flower | 71 |

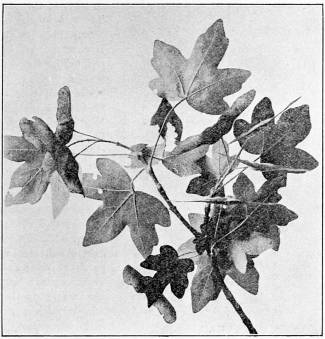

| The Oak in Flower | 72 |

| The Beech in Fruit | 73 |

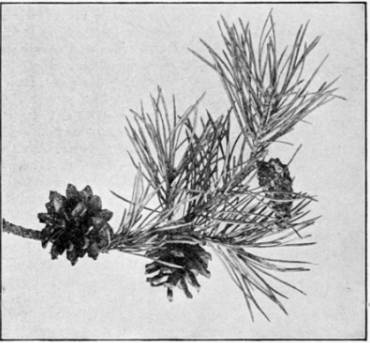

| The Scots Pine, with Cones | 78 |

| The Yew in Fruit | 79 |

| Waysides and Wastes in Spring | |

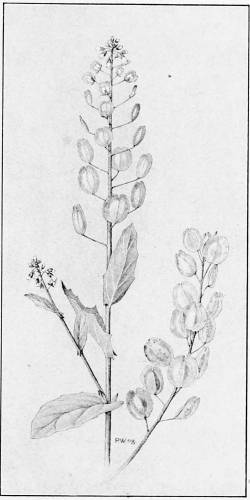

| The Shepherd's Purse | 82 |

| The Scurvy Grass | 83 |

| The Common Whitlow Grass | 83 |

| The Yellow Rocket | 84 |

| The Procumbent Pearlwort | 86 |

| The Greater Stitchwort | 87 |

| The Chickweed | 88 |

| The Broad-leaved Mouse-ear Chickweed | 89 |

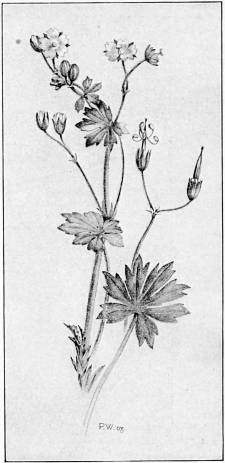

| The Dove's-foot Crane's-bill | 90 |

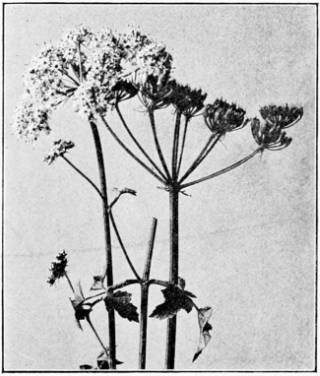

| The Jagged-leaved Crane's-bill | 91 |

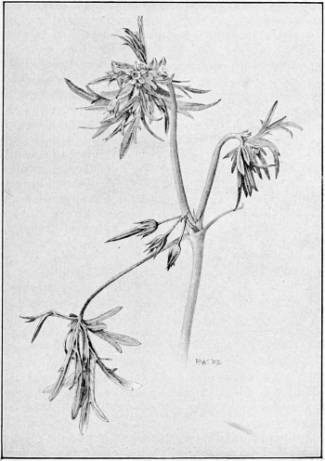

| The Herb Robert | 92 |

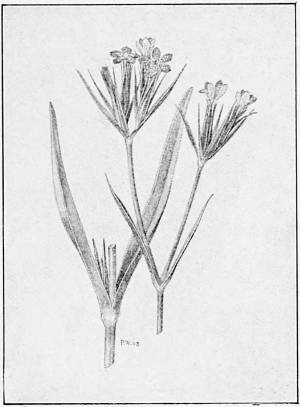

| The Grass Vetchling | 93 |

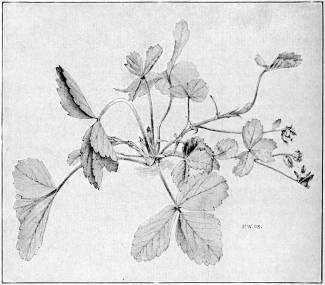

| The Strawberry-leaved Cinquefoil | 94 |

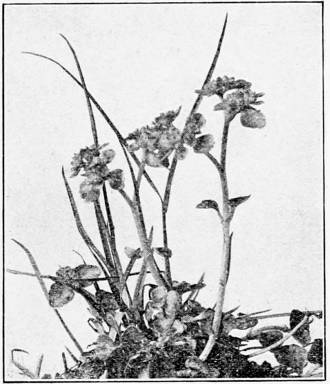

| The Moschatel | 95 |

| The White Bryony | 96 |

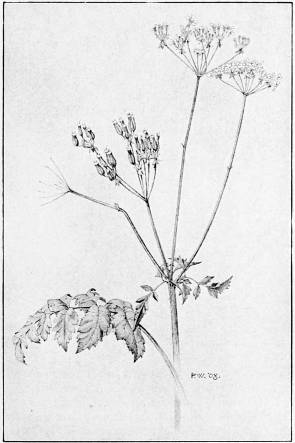

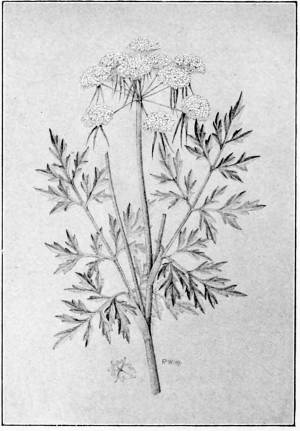

| The Wild Beaked Parsley | 97 |

| The Garden Beaked Parsley | 98 |

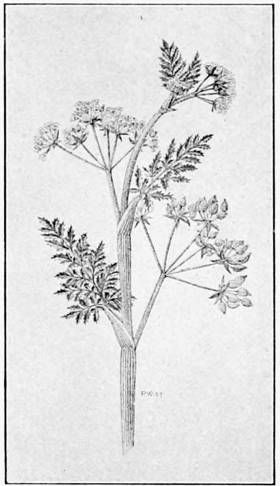

| The Goutweed | 99 |

| The Crosswort | 100 |

| The Colt's-foot in Early Spring | 101 |

| The Germander Speedwell | 101 |

| The White Dead Nettle | 102 |

| The Yellow Pimpernel | 103 |

| The Dog's Mercury | 104 |

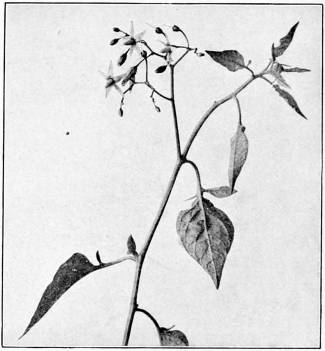

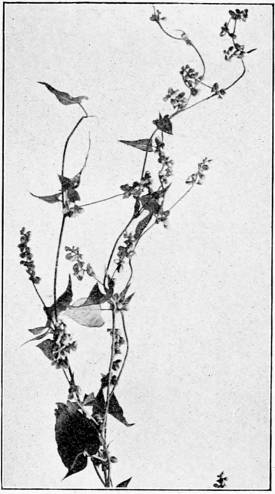

| The Black Bryony | 105 |

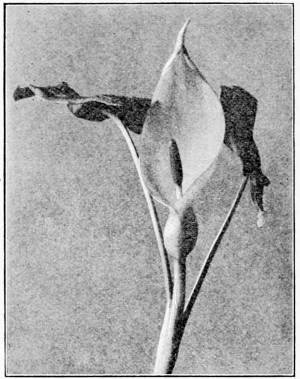

| The Wild Arum | 106 |

| Meadows, Fields, and Pastures—Spring | |

| The Field Pennycress | 109 |

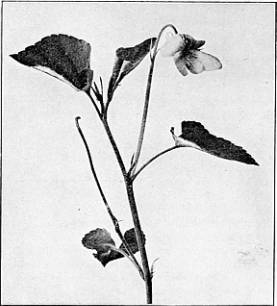

| The Wild Pansy | 110 |

| The Ragged Robin | 111 |

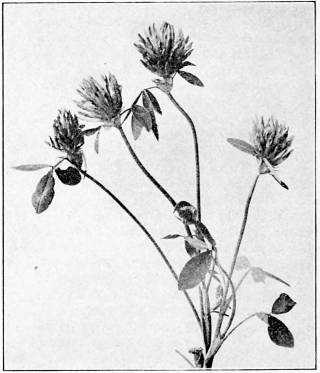

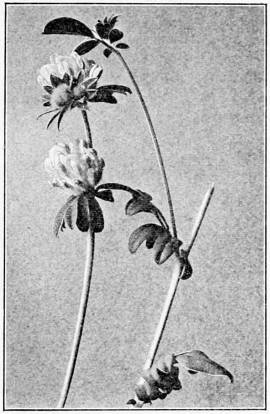

| The Purple Clover | 114 |

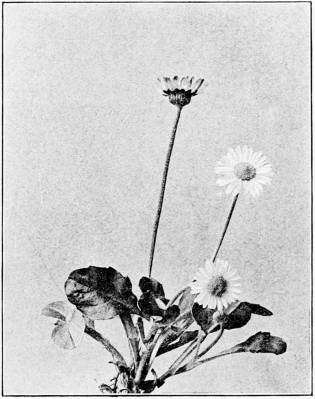

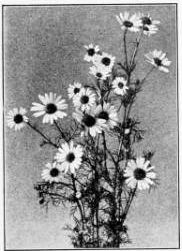

| The Daisy | 115 |

| The Butterbur | 117 |

| The Yellow Rattle | 118 |

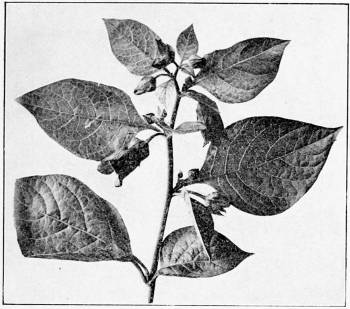

| The Henbit Dead Nettle | 119 |

| The Cowslip | 120 |

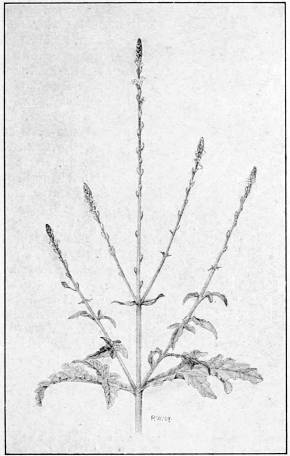

| The Fox-tail Grass | 121 |

| Bogs, Marshes, and Wet Places in Spring | |

| The Marsh Potentil | 124 |

| The Golden Saxifrage | 125 |

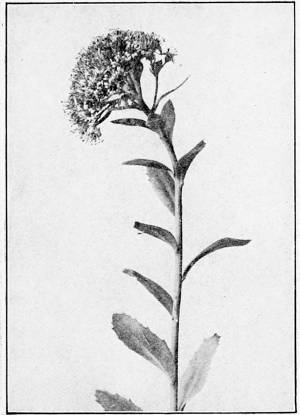

| The Marsh Valerian | 126 |

| The Marsh Trefoil | 127 |

| The Marsh Lousewort | 127 |

| The Yellow Flag | 128 |

| Woods and Thickets in Summer | |

| The Large-flowered St. John's-wort | 131 |

| The Common St. John's-wort | 132 |

| The Dyer's Greenweed | 133 |

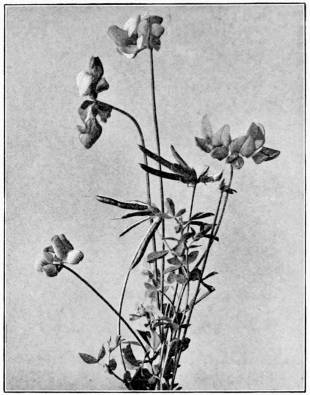

| The Sweet Milk Vetch | 134 |

| The Wild Raspberry | 135 |

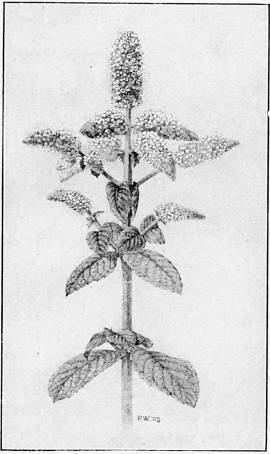

| The Rose Bay Willow Herb | 136 |

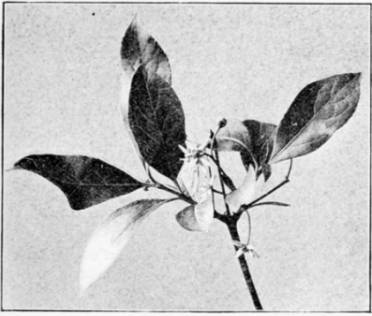

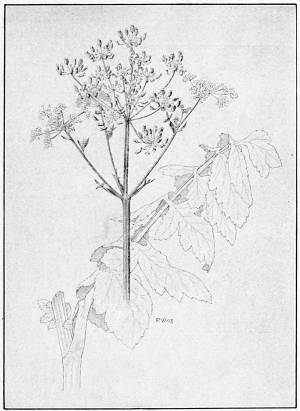

| The Dogwood | 137 |

| The Wood Sanicle | 138 |

| The Alexanders | 139 |

| The Elder | 140 |

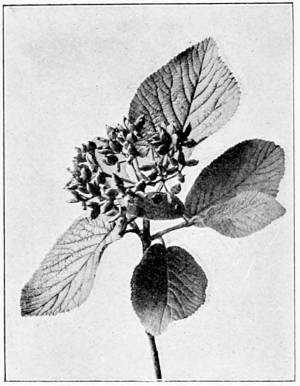

| The Guelder Rose | 141 |

| The Saw-wort | 143 |

| The Ivy-leaved Bell-flower | 145 |

| Twigs of Holly | 146 |

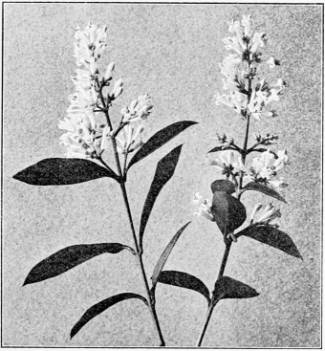

| The Privet | 147 |

| The Millet Grass | 148 |

| The Bearded Wheat | 148 |

| The Slender False Brome | 149 |

| Wastes and Waysides in Summer | |

| The Wild Clematis | 152 |

| The Hedge Mustard | 152 |

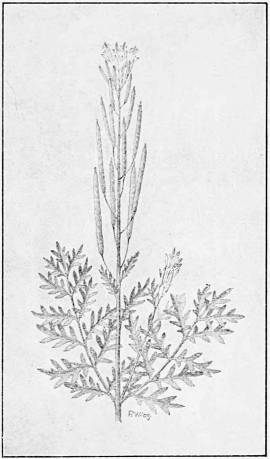

| The Felix Weed | 153 |

| The Dyer's Weed | 154 |

| The Deptford Pink | 155 |

| The Red Campion | 156 |

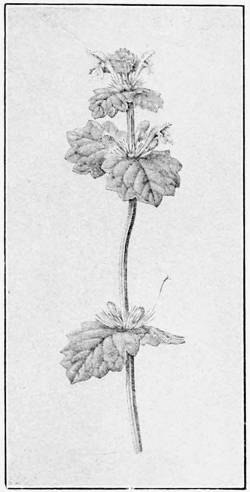

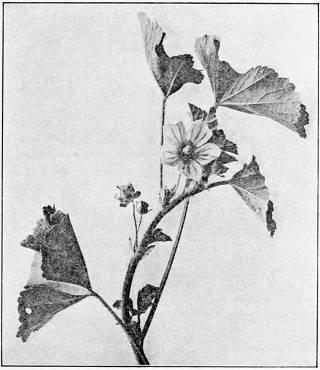

| The Common Mallow | 157 |

| The Musk Mallow | 158 |

| The Bloody Crane's-bill | 159 |

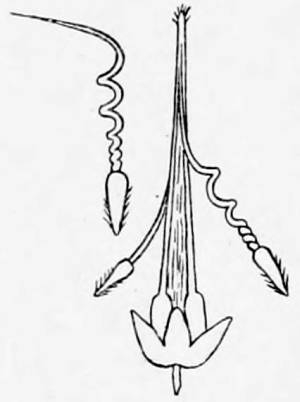

| The Fruit of the Stork's-bill | 160 |

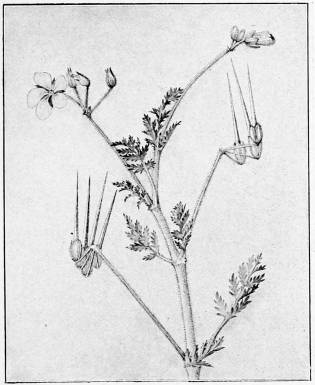

| The Hemlock Stork's-bill | 161 |

| The Bird's-foot Trefoil | 162 |

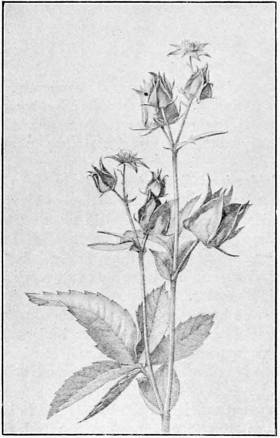

| The Herb Bennet or Geum | 163 |

| The Dog Rose | 164 |

| The Silver Weed | 164 |

| The Agrimony | 165 |

| The Orpine or Livelong | 167 |

| The Fool's Parsley | 168 |

| The Wild Parsnip | 169 |

| The Cow Parsnip or Hogweed | 170 |

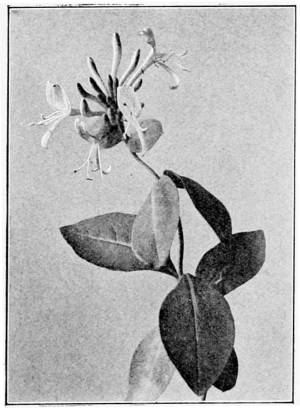

| The Honeysuckle | 171 |

| The Great Hedge Bedstraw | 172 |

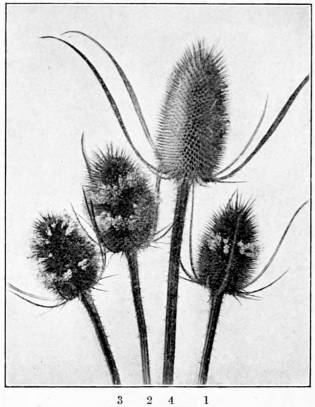

| The Teasel | 173 |

| Teasel Heads | 174 |

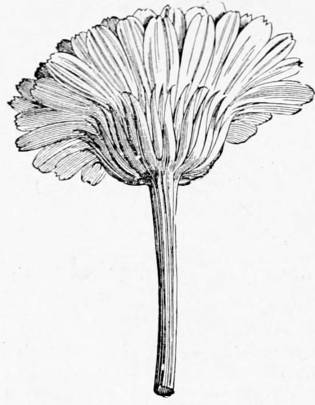

| Flower Head of the Marigold | 176 |

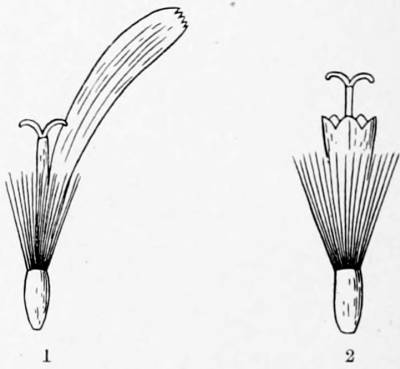

| Florets of a Composite Flower | 176 |

| The Yellow Goat's-beard | 177 |

| The Hawkweed Picris | 178 |

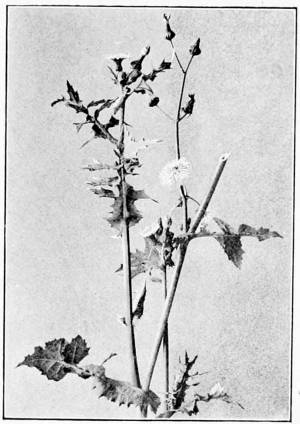

| The Prickly Lettuce | 179 |

| The Sharp-fringed Sow-Thistle | 180 |

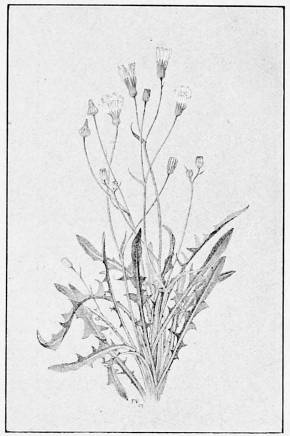

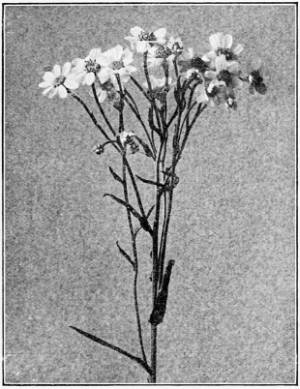

| The Smooth Hawk's-beard | 181 |

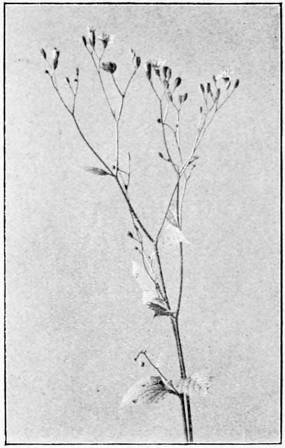

| The Nipplewort | 182 |

| The Burdock | 183 |

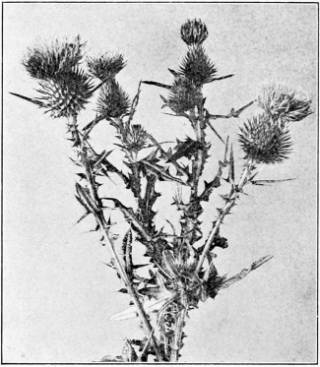

| The Spear Thistle | 184 |

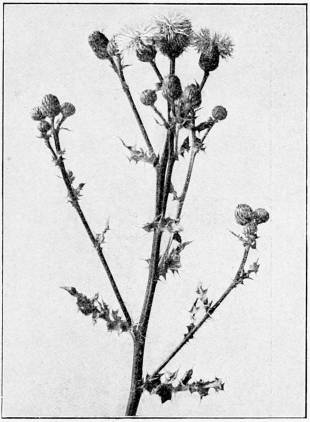

| The Creeping Thistle | 185 |

| The Tansy | 186 |

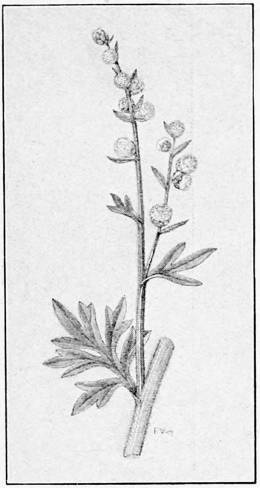

| The Wormwood | 187 |

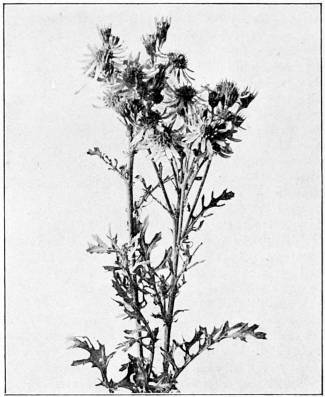

| The Ragwort | 188 |

| The Scentless Mayweed | 189 |

| The Yarrow or Milfoil | 189 |

| The Rampion Bell-flower | 191 |

| The Great Bindweed | 192 |

| The Henbane | 193 |

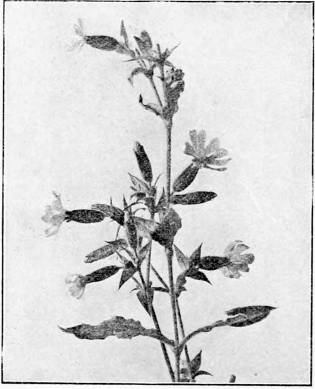

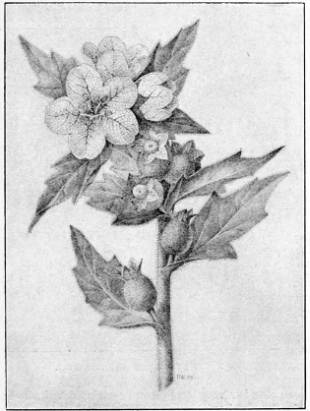

| The Woody Nightshade or Bittersweet | 194 |

| The Deadly Nightshade | 195 |

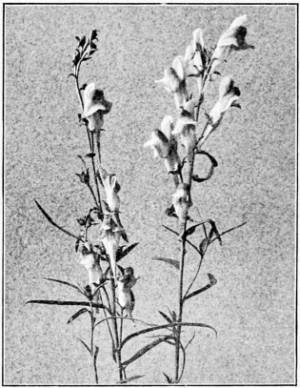

| The Yellow Toadflax | 196 |

| The Vervein | 197 |

| The Balm | 198 |

| The Hedge Woundwort | 199 |

| The Gromwell | 201 |

| The Hound's-tongue | 202 |

| The White Goosefoot | 203 |

| The Spotted Persicaria | 205 |

| The Curled Dock | 207 |

| The Great Nettle | 208 |

| The Canary Grass | 209 |

| Meadows, Fields, and Pastures—Summer | |

| The Gold of Pleasure | 212 |

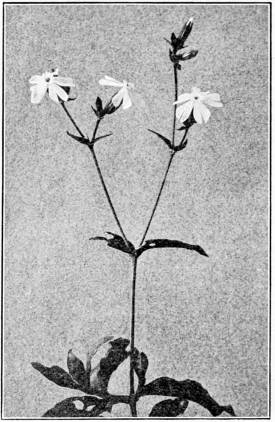

| The Bladder Campion | 213 |

| The White Campion | 214 |

| The Kidney Vetch | 215 |

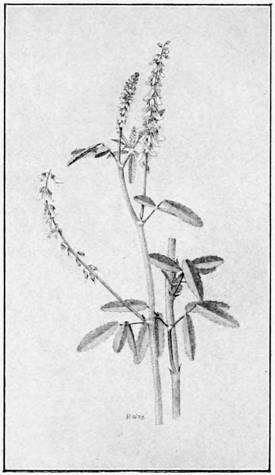

| The Common Melilot | 216 |

| The Lady's Mantle | 217 |

| The Meadow Sweet | 219 |

| The Burnet Saxifrage | 220 |

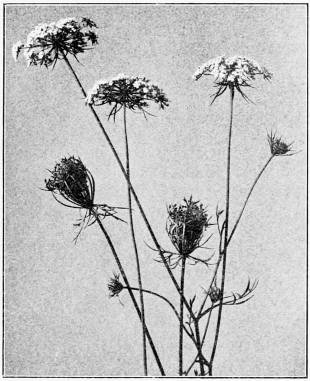

| The Wild Carrot | 221 |

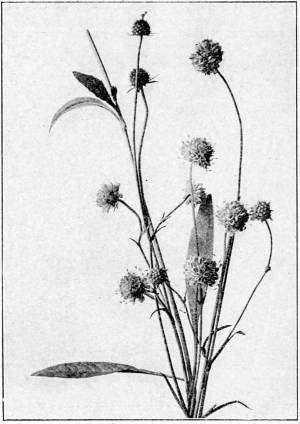

| The Devil's-bit Scabious | 222 |

| The Rough Hawkbit | 223 |

| The Autumnal Hawkbit | 224 |

| The Meadow Thistle | 225 |

| The Black Knapweed | 226 |

| The Great Knapweed | 226 |

| The Common Fleabane | 227 |

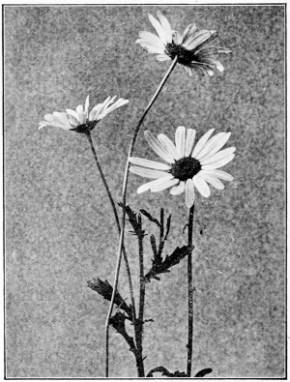

| The Ox-eye Daisy | 228 |

| The Sneezewort | 229 |

| The Small Bindweed | 230 |

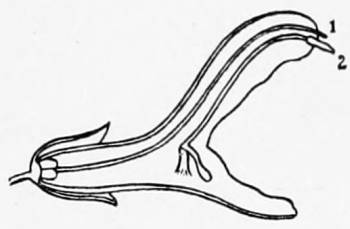

| Section of the Flower of Salvia | 231 |

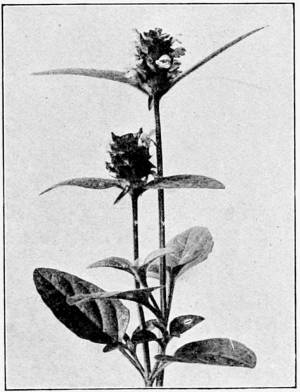

| The Self-heal | 231 |

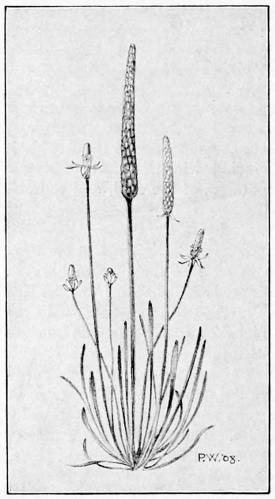

| The Ribwort Plantain | 232 |

| The Butterfly Orchis | 233 |

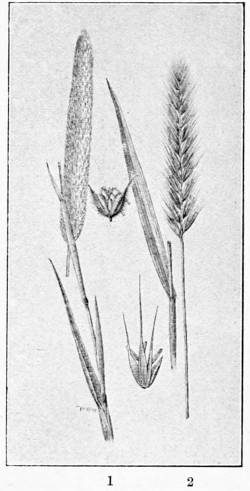

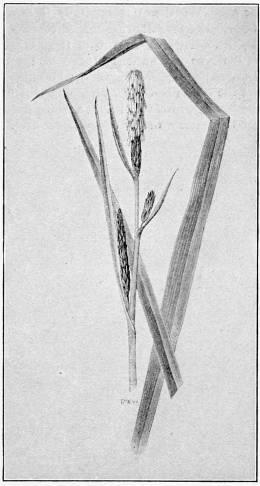

| The Cat's-tail Grass | 233 |

| The Meadow Barley | 233 |

| The Rye Grass or Darnel | 234 |

| The Sheep's Fescue | 234 |

| Bogs, Marshes, and Wet Places—Summer | |

| The Lesser Spearwort | 237 |

| The Great Hairy Willow Herb | 238 |

| The Purple Loosestrife | 239 |

| The Water Hemlock | 241 |

| The Common Water Dropwort | 242 |

| The Marsh Thistle | 243 |

| The Brooklime | 244 |

| The Water Figwort | 245 |

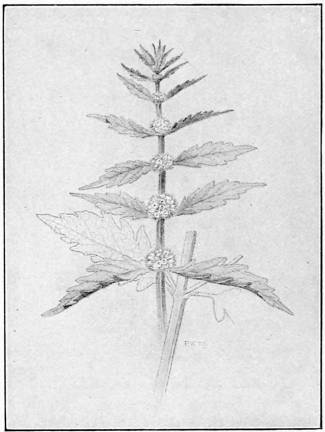

| The Gipsy wort | 246 |

| The Round-leaved Mint | 247 |

| The Forget-me-not | 248 |

| The Water Pepper or Biting Persicaria | 249 |

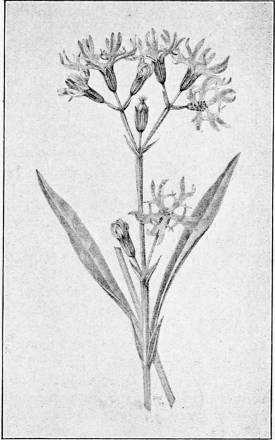

| The Bog Asphodel | 251 |

| The Common Rush | 252 |

| The Shining-fruited Jointed Rush | 253 |

| The Common Sedge | 254 |

| The Marsh Sedge | 255 |

| Heath, Down, and Moor | |

| The Milkwort | 258 |

| The Broom | 259 |

| The Furze or Gorse | 260 |

| The Tormentil | 261 |

| The Smooth Heath Bedstraw | 264 |

| The Dwarf Thistle | 265 |

| The Carline Thistle | 267 |

| The Common Chamomile | 268 |

| The Harebell | 269 |

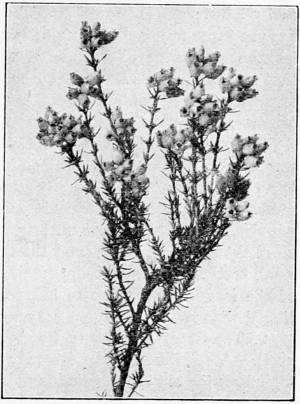

| The Cross-leaved Heath | 270 |

| The Bell Heather or Fine-leaved Heath | 271 |

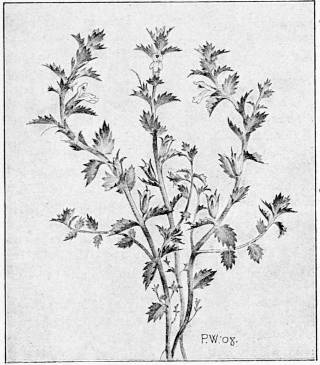

| The Eyebright | 273 |

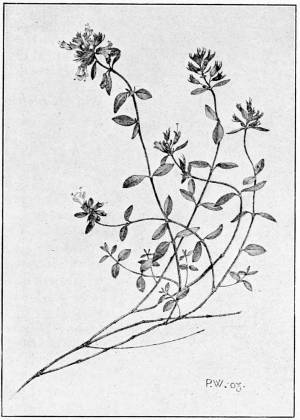

| The Wild Thyme | 275 |

| The Autumnal Lady's Tresses | 276 |

| The Butcher's Broom | 277 |

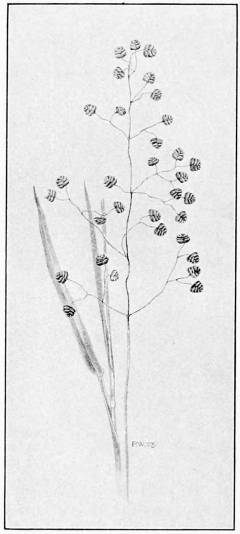

| The Common Quaking Grass | 278 |

| The Common Mat Grass | 279 |

| In the Corn Field | |

| The Mousetail | 282 |

| The Common Red Poppy | 284 |

| The White or Opium Poppy | 285 |

| The Fumitory | 287 |

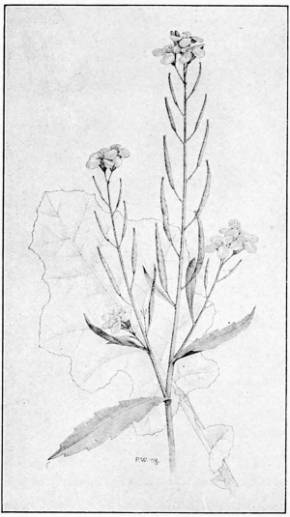

| The Black Mustard | 288 |

| The Corn Spurrey | 289 |

| The Shepherd's Needle or Venus's Comb | 290 |

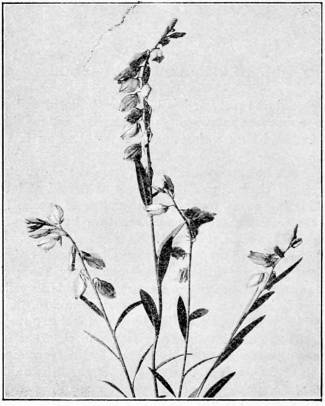

| The Venus's Looking Glass or Corn Bell-flower | 291 |

| The Scarlet Pimpernel | 292 |

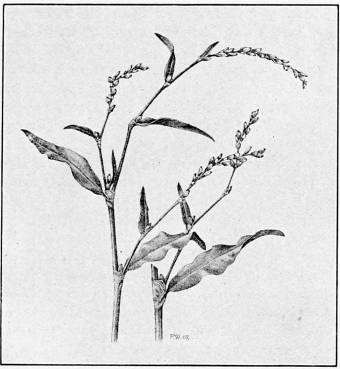

| The Climbing Bistort | 293 |

| The Dwarf Spurge | 294 |

| On the Chalk | |

| The Rock Rose | 297 |

| The Sainfoin | 300 |

| The Salad Burnet | 301 |

| The Field Gentian | 302 |

| The Yellow-wort | 303 |

| The Great Mullein | 304 |

| The Red Hemp Nettle | 305 |

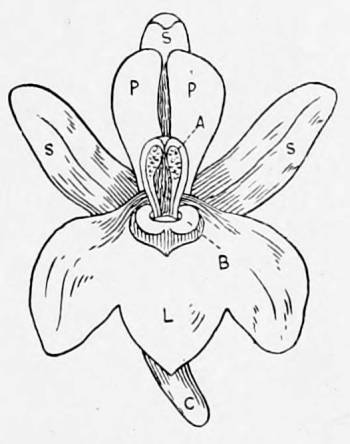

| An Orchis Flower | 307 |

| The Sweet-scented Orchis | 309 |

| By the River Side | |

| The Common Meadow Rue | 313 |

| The Hemp Agrimony | 314 |

| The Common Skull-cap | 315 |

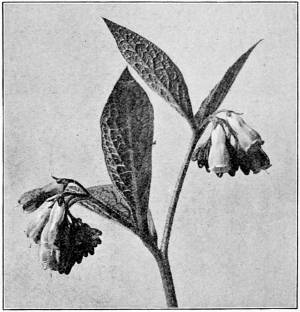

| The Comfrey | 316 |

| On Walls, Rocks and Stony Places | |

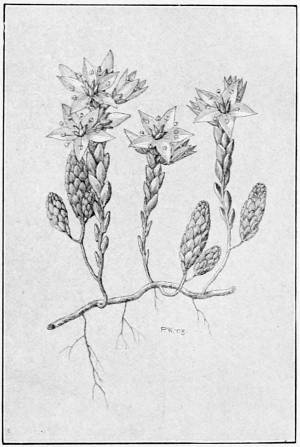

| The Biting Stonecrop or Wall Pepper | 321 |

| The Wall Pennywort or Navelwort | 322 |

| The London Pride | 323 |

| The Mossy Saxifrage | 324 |

| The Ivy-leaved Toadflax | 325 |

| The Wall Pellitory | 326 |

| Autumn in the Woods | |

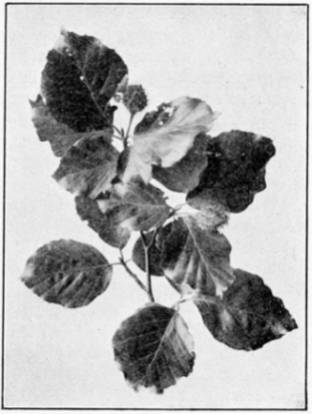

| The Alder in Autumn | 333 |

| The Ash in Autumn | 336 |

| The Maple in Fruit | 337 |

| The Wayfaring Tree in Fruit | 338 |

| The Strawberry Tree | 339 |

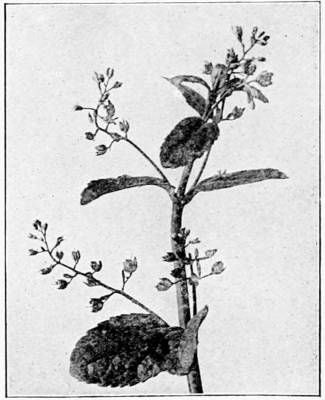

| Parasitic Plants | |

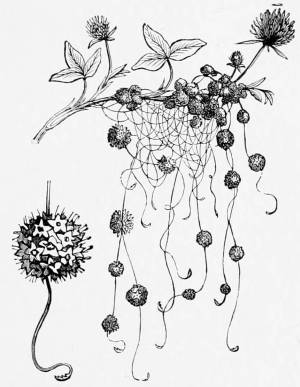

| The Greater Dodder | 342 |

| The Clover Dodder | 343 |

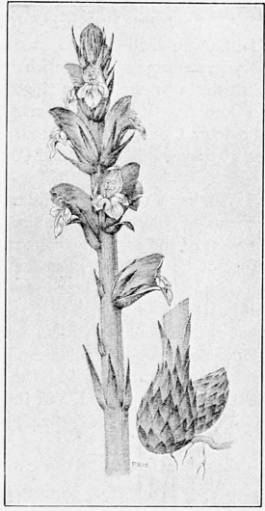

| The Great Broomrape | 345 |

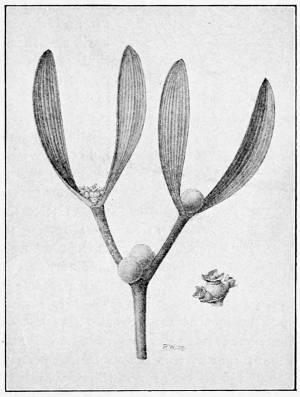

| The Mistletoe | 347 |

| A Young Mistletoe Plant | 348 |

| Carnivorous Plants | |

| The Greater Bladder-wort | 351 |

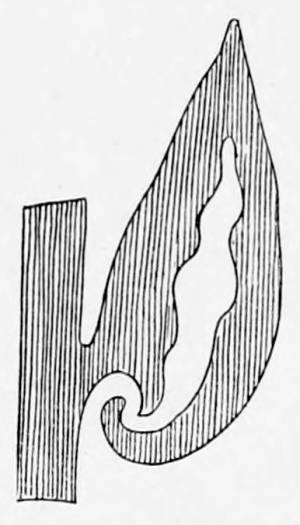

| Longitudinal section through the leaf of the Toothwort | 352 |

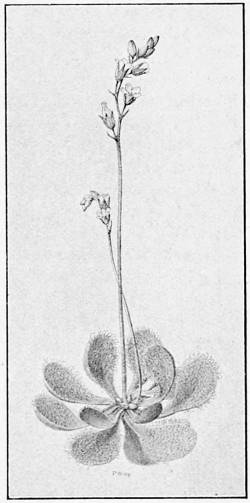

| The Common Butterwort | 353 |

| The Round-leaved Sundew | 355 |

FIELD

AND

WOODLAND PLANTS

The beginner will often find it difficult, and sometimes quite impossible, to identify some of the flowers seen or gathered during a country ramble; and he will hardly be surprised to experience many disappointments in his attempts to do this when he realises the large number of species among our flowering plants, and the very close resemblance that allied species frequently bear to one another. But there are right and wrong methods of setting to work for the purpose of determining the identity of a plant, and the object of this chapter is to put the beginner on the right track. He must remember, however, that the aid given here is intended to assist him principally in the identification of the commoner species, though it may, at the same time, help him to determine the natural affinities or relationships of other flowers that fall in his way.

The directions we are about to give the reader regarding this portion of his work will be understood by him only if he is fairly well acquainted with the general characters of a flowering plant and with the structure of flowers; and as it would hardly be advisable to assume such knowledge, we shall give a brief outline of this part of the subject, dealing only with those points that are essential to our purpose, and explaining the meaning of those terms which are commonly employed in the description of plants and their flowers.

The root is that portion of the plant which descends into the soil for the absorption of the mineral food required. It really serves a double purpose, for, in addition to the function just mentioned, it fixes the plant in its place, thus forming a basis of support for the stem and its appendages.

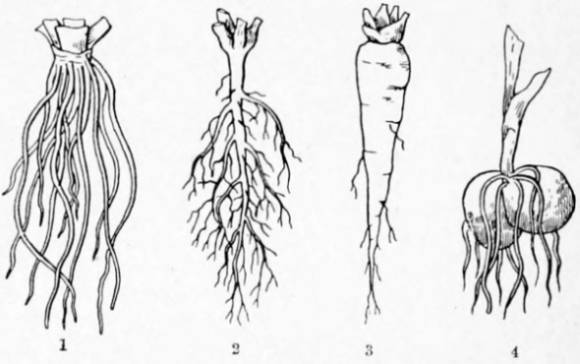

Forms of Roots

1. Simple fibrous. 2. Branched fibrous. 3. Tap root. 4. Tuberous root.

Roots are capable of absorbing liquids only, and all fertile soils contain more or less soluble mineral matter which is dissolved by the moisture present. This matter is absorbed mainly by the minute root-hairs—outgrowths of the superficial cells—which are to be found on the rootlets or small branches that are given off from the main descending axis.

The principal forms of roots occurring in our flowering plants are:—

1. The simple fibrous root, consisting of unbranched fibres such as we see in the Bulbous Buttercup and the Common Daisy.

2. The branched fibrous root, as that of the Chickweed and Grasses.

3. The tap root, which is thick above and tapers downwards, like the roots of the Dandelion, Carrot and Wild Parsnip.

4. The tuberous root, common among the Orchids.

5. The creeping root, possessed by some Grasses in addition to their fibrous roots.

Besides these common forms there are roots of a somewhat exceptional character, such as the aerial roots or suckers which grow from the stem of the Ivy and serve to support the plant; and the roots of the Mistletoe, which, instead of penetrating the soil, force their way into the substance of certain trees, from which they derive the necessary nourishment.

The student of plant life must always be careful to distinguish between roots and underground stems, for there are many examples of creeping and tuberous stems which resemble certain roots in general appearance. A true root bears no buds, and, therefore, is not capable of producing new plants. If a root creeps under the ground, as does the root of the Barley Grass, it merely serves the purpose of collecting nourishment from a wider area—a matter of considerable importance when the soil is dry and deficient in suitable mineral food. A creeping stem, on the other hand, developes buds as it proceeds, each bud giving rise to a new plant; and the creeping itself is the result of the growth of a permanent terminal bud.

Again, when studying plants for the purpose of identification, it is often important to note whether the root is annual, biennial, or perennial; that is, whether the root lives for one season only, lives throughout the winter, and supports the plant for a second season, or retains its life for an indefinite number of years.

Most of the roots that live over one season are of a fleshy nature, thick and tapering, or tuberous, and contain more or less stored nourishment which assists the new growths that are called forth by the warmth and light of the early spring sun.

The stems of plants exhibit a much greater variety of structure and habit than do the roots. Their chief functions are to support the leaves and flowers, and to arrange these parts in such a manner that they obtain the maximum of light and air; also to form a means of communication by which the sap may pass in either direction. Stems also frequently help to protect the plant, either by the development of thorns or prickles, or by producing hairs which prevent snails and slugs from reaching and devouring the leaves and flowers.

The character of the stem is often of some importance in determining the species, so we must now note the principal features that should receive our attention.

As regards surface, the stem may be smooth or hairy. In general form, as seen in transverse section, it may be round, flattened, triangular, square, or traversed longitudinally by ridges and furrows more or less distinct. Flattened stems are sometimes more or less winged with leaf-like extensions, as in the Everlasting Pea, in which case the wings perform the functions of foliage leaves. It should also be noted whether the stems are herbaceous, or woody, and whether they are hollow, or jointed.

In some plants the stem is so short that the leaves appear to start direct from the root, as in the Dandelion and Primrose. Such stems are said to be inconspicuous.

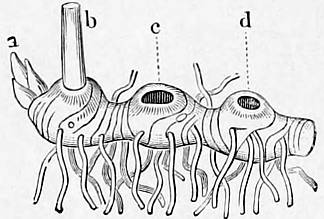

Running Underground Stem of Solomon's Seal

a, Terminal bud from which the next

year's stem is developed; b, Stem of the present year; c, and d, Scars of the

stems of previous years.

The longer and conspicuous stems are either simple or branched, and they may be erect, prostrate, trailing, climbing, or running. In the case of climbing stems it should be noted whether the necessary support is obtained by means of tendrils, rootlets, or suckers, or by the twining of the stem itself.

Running stems are those which run along the surface of the ground by the continued growth of a terminal bud, and produce new plants at intervals, as in the case of the Wild Strawberry. Many stems, however, creep under the ground, and these should always be distinguished from running roots, from which they may be known by the production of buds that develop into new plants, as in the Iris and Solomon's Seal.

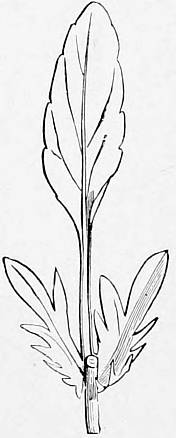

The arrangement of the leaves on the stem is a matter of great importance for purposes of identification. Especially should it be noted whether the leaves are opposite, alternate, whorled (arranged in circles round the stem), or radical (apparently starting direct from the root).

Some leaves have smaller leaves or scales at their bases, that is, at the points where they are attached to the stem of the plant. Such leaves or scales are termed stipules. They are often so well[5] developed that they are as conspicuous as the ordinary foliage leaves, and in such instances they perform the functions of the latter. The presence and character of the stipules should always be noted. A leaf without stipules is said to be exstipulate.

Arrangement of Leaves

1. Opposite. 2. Alternate. 3. Whorled.

Leaf of the Pansy with Two Large Stipules.

A leaf usually consists of two distinct parts—the petiole or stalk, and the lamina or blade. Some, however, have no petiole, but the blade is in direct contact with the stem. These leaves are said to be sessile, and some of them clasp the stem, or even extend downwards on the stem, forming a wing or a sheath.

A leaf is said to be simple when the blade is in one continuous whole, even though it may be very deeply divided; but when the blade is cut into distinct parts by incisions that extend quite into the midrib (the continuation of the stalk to the tip of the leaf), the leaf is compound.

The student must be careful to distinguish between compound leaves and little branches or twigs bearing several simple leaves, for they are often very similar in general appearance. The compound leaf may always be known by the total absence of buds, and often by the presence of one or more stipules at the base of its stalk; while a branch bearing a similar appearance usually has a terminal bud, also buds in the exils of its leaves, and never any stipules at the point where it originates. The distinct parts of compound leaves are termed leaflets.

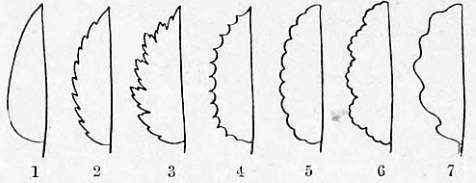

Attention to the form and character of the leaf is often of as much importance as the observation of the flower in the determination of species. Not only should we note the general shape of the leaf, but also the character of its surface, its margin, and its apex. The surface may be smooth, hairy, downy, velvety, shaggy, rough, wrinkled or dotted. The margin is said to be entire when it is not broken by incisions of any kind. If not entire it may be toothed, serrate (sawlike), crenate or wavy. Sometimes it happens that the teeth bear still smaller teeth, in which case the margin is said to be doubly toothed; or, if the teeth are sawlike, it is doubly serrate. As regards the apex, it is generally sufficient to note whether it is acute (sharp), obtuse (blunt), or bifid (divided into two).

Margins of Leaves

1. Entire. 2. Serrate or sawlike. 3. Doubly serrate. 4. Dentate or

toothed. 5. Crenate. 6. Doubly crenate. 7. Sinuate or wavy.

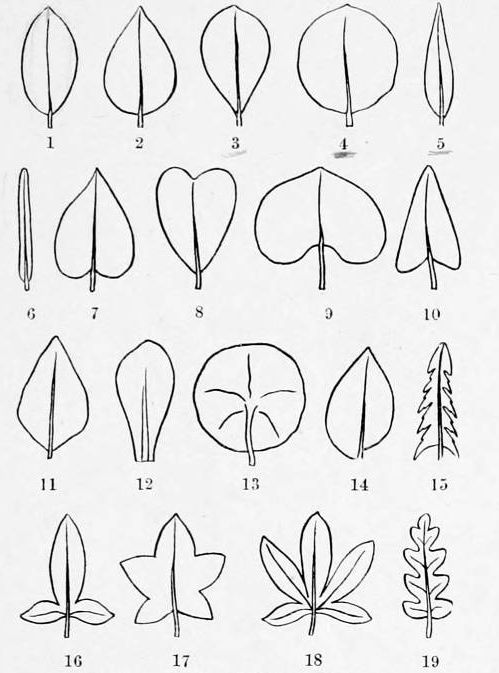

It is not necessary to describe separately all the principal forms of simple and compound leaves. These are illustrated, and the student should either make himself acquainted with the terms applied to the different shapes, or refer, as occasion requires, to the illustrations. Concerning the compound leaves, however, their segments are themselves sometimes divided after the manner of the whole, and even the secondary segments may be similarly cut. Thus, if the segments of a pinnate leaf are themselves pinnately compound, the leaf is said to be bi-pinnate; and, if the secondary segments are also compound, it is a tri-pinnate leaf.

We must now turn our attention to the different kinds of inflorescence or arrangement of flowers. Flowers are commonly mounted on stalks (peduncles), but in many cases they have no stalks, being attached directly to the stem of the plant, and therefore said to be sessile. Whether stalked or sessile, if they arise from the axils of the leaves—the angles formed by the leafstalks and the stem—they are said to be axillary. When only one flower grows on a stalk it is said to be solitary; but in many cases we find a number of flowers on one peduncle, in which instances, should each flower of the cluster have a separate stalk of its own, the main stalk only is called the peduncle, and the lesser stalks bearing the individual flowers are the pedicels.

Various Forms of Simple Leaves

1. Oval or elliptical.

2. Ovate.

3. Obovate.

4. Orbicular.

5. Lanceolate.

6. Linear.

7. Cordate (heart-shaped).

8. Obcordate.

9. Reniform (kidney-shaped).

10. Sagittate (Arrow-shaped).

11. Rhomboidal.

12. Spathulate (spoon-shaped).

13. Peltate (stalk fixed to the centre).

14. Oblique.

15. Runcinate (lobes pointing more or less downwards).

16. Hastate (halberd-shaped).

17. Angled.

18. Palmate.

19. Pinnatifid.

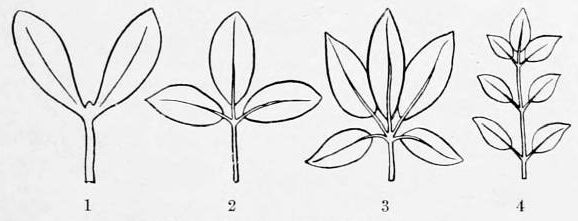

Forms of Compound Leaves

1. Binate. 2. Ternate. 3. Digitate. 4. Pinnate.

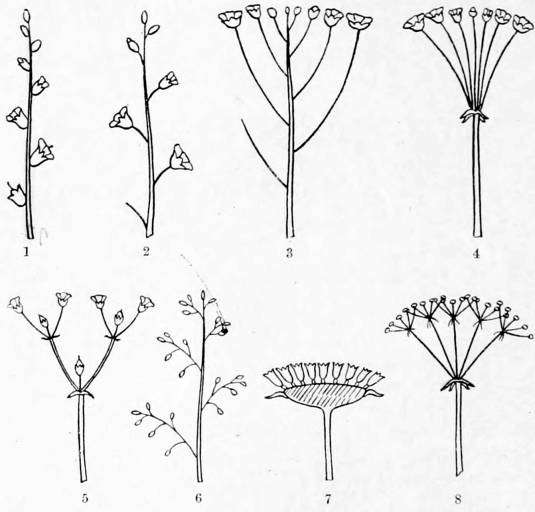

Forms of Inflorescence

1. Spike. 2. Raceme. 3. Corymb. 4. Umbel. 5. Cyme. 6. Compound

Raceme or Panicle. 7. Capitulum or Head. 8. Compound Umbel.

It is often convenient to make use of certain terms to denote the various arrangements of flower-clusters, and the principal of these are as follows:—

1. Spike.—Sessile flowers arranged along a common axis.

2. Raceme.—Flowers stalked along a common axis.

3. Corymb.—Flowers stalked along a common axis, but the lengths of the pedicels varying in such a manner as to bring all the flowers to the same level.

4. Umbel.—The pedicels all start from the same level on the peduncle.

5. Cyme.—An arrangement in which the flower directly at the end of the peduncle opens first, followed by those on the branching pedicels.

6. Panicle.—A compound raceme—a raceme the pedicels of which are themselves branched.

7. Capitulum or Flower-head.—A dense cluster of flowers, all attached to a common broad disc or receptacle.

Other forms of inflorescence may also be compound. Thus, a compound umbel is produced when the pedicels of an umbel are themselves umbellate.

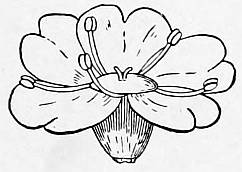

A flower, if complete in all its parts, consists of modified leaves arranged in four distinct whorls, the parts being directly or indirectly attached to a receptacle.

The outer whorl is the calyx, and is composed of parts called sepals, which may be either united or distinct. The calyx is usually green; but, in some cases, is more or less highly coloured. Sometimes the calyx is quite free from the pistil or central part of the flower, the sides of which are thus left naked, and the calyx is then said to be inferior. If, however, it is united to the surface of the pistil it is superior. When it remains after other parts of the flower have decayed, it is said to be persistent.

The second whorl—the corolla—is usually the whorl that gives most beauty to the flower. It is composed of parts, united or distinct, called petals.

Both calyx and corolla vary very considerably in shape. They may be cup-shaped, tubular, bell-shaped, spreading, funnel-shaped, lipped, &c. If the sepals and petals are arranged symmetrically round a common centre, the calyx and corolla, respectively, are said to be regular; if otherwise, they are irregular.

The third whorl consists of the stamens, each of which, in its most perfect form, is made up of a filament or stalk, and an anther which, when mature, splits and sets free the pollen that is formed within it. Sometimes the stamen has no filament, and the anther is then said to be sessile.

The mode of attachment of the stamens is very variable. They[10] may grow from immediately below the pistil, or from its summit; or they may be attached to either the petals or the sepals. The filaments are usually distinct, but sometimes they are united in such a manner as to form a tube, or grow into two or more bundles. The anthers are usually distinct, even when the filaments are united; but these sometimes grow together.

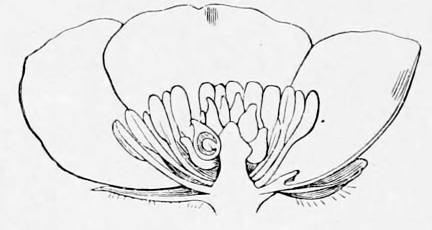

Longitudinal Section Through the Flower of the Buttercup

Showing the calyx, corolla, stamens and pistil. The pistil consists of several

distinct carpels, one of which is represented in section to show its single ovule.

The central part of the flower is the pistil, and this is made up of one or more parts called carpels. Each carpel, when distinct, is a hollow case or ovary, prolonged above into one or more stalks or styles, tipped by a viscid secreting surface called the stigma. The ovary contains the ovules, attached to a surface called the placenta; and these ovules, after having been impregnated by the pollen, develop into seeds which are plants in embryo. The ovary may have no style, and the stigma is then sessile.

Where the pistil consists of more than one carpel, these carpels may unite in such a manner as to form a single cell, or an ovary of two or more cells. In other cases the carpels remain quite distinct, thus forming a number of distinct ovaries, each with its own stigma. For purposes of identification it is often necessary to note the position of the placenta. This may be at the side of the ovary, in which case it is said to be parietal; or it may stand up in the centre of the ovary, without any attachment to the sides, when it is described as free central. If, however, it occupies the centre of the ovary, but is attached by means of radiating partitions to the sides, it is termed axile.

If the ovary is quite free in the centre of the flower, the surrounding parts being attached below it, it is said to be superior; but if the perianth (p. 11) adheres to it, it is inferior.

A leaf or scale will often be observed at the foot of a flower stalk or at the base of a sessile flower. This is termed a bract, and a flower possessing a bract is said to be bracteate. The bract is[11] sometimes so large that it almost completely encloses the flower, or even a cluster of flowers.

Inferior (1) and Superior (2) Ovary.

The flower is the reproductive part of the plant, being concerned in the production of the seeds; but the organs directly connected with the seed-formation are the pistil and the stamens, the former containing the ovules, and the latter producing the pollen cells by means of which the ovules are impregnated. Thus the stamens and the pistil are the essential parts of the flower, though the corolla and the calyx may perform some subsidiary function in connexion with the reproduction of the species.

This being the case, a flower may be described as perfect if it consists of stamens and pistil only, without any surrounding calyx or corolla; and imperfect if it possesses no pistil or no stamens, regardless of the presence or absence of calyx and corolla.

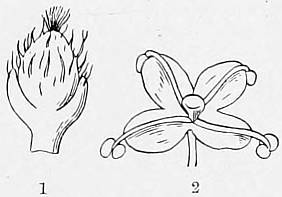

Unisex Flowers of the Nettle

1. Pistillate. 2. Staminate.

The two outer whorls of a well-developed perfect flower (calyx and corolla) together form the perianth. Some flowers, however have only one whorl outside the anthers, representing both the calyx and corolla of the more highly organised flower. This one whorl, therefore, is the perianth, and its parts are not correctly termed either petals or sepals, since they represent both.

A perfect flower is sometimes spoken of as bisexual, for it includes the two sexual organs of the plant—the ovary or female part, producing the ovules; and the stamens or male part, which is concerned in the impregnation or fertilisation of the ovules.

Many plants produce only unisexual (and therefore imperfect)[12] flowers, which contain either no stamens or no pistil. If such possess stamens and no pistil, they are called staminate or male flowers; and if pistil and no stamens, pistillate or female flowers. These two kinds are sometimes borne on the same plant, when they are said to be monœcious; but often on separate plants (diœcious), as in some of the Nettleworts and the Willow Tree. Spikes of unisexual flowers, such as are common among our forest trees, are called catkins.

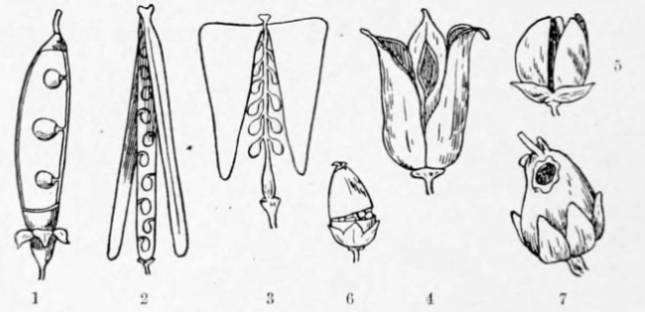

Dehiscent Fruits

1. Pod. 2. Siliqua. 3. Silicula.

4. Follicles(cluster of three). 5. Capsule splitting longitudinally.

6. Capsule splitting transversely. 7. Capsule splitting by pores.

After the ovules have been impregnated by the pollen they develop into seeds, each of which consists of or contains an embryo plant; and, at the same time, the ovary itself enlarges, changing its character more or less, till it becomes a ripened fruit.

Fruits vary very considerably in their general characters, but may be divided into two main groups—those that split when ripe (dehiscent fruits) and those which do not split (indehiscent fruits).

The principal forms of dehiscent fruits are:—

1. The pod or legume, which splits into two valves, with placenta on one side.

2. The siliqua, a long, narrow fruit that splits into two valves which separate from a membrane with placenta on both sides.

3. The silicula, of the same nature as the siliqua, but about as broad as it is long.

4. The follicle, which splits on one side only, through the placenta.

5. All other fruits that split are termed capsules. Some of these split longitudinally, some transversely, and others by forming pores for the escape of the seeds.

The chief kinds of indehiscent fruits are:—

1. The drupe or stone-fruit, which consists of a hard stone surrounded by a fleshy covering, as the plum and the cherry.

2. The berry, which is soft and fleshy, and contains several seeds, like the currant and the grape.

3. The nut or achene—a fruit with hard and dry walls, as the filbert and the acorn.

4. The samara or winged fruit, like that of the sycamore.

Various modifications of these indehiscent fruits are to be met with; thus, the blackberry is not really a berry, but a cluster of little drupes formed from a single pistil of many carpels. A berry, too, may be made up of many parts, as is the case with the orange. The apple and similar fruits consist of a core (the true fruit) surrounded by a fleshy mass that is produced from the receptacle of the flower; and the strawberry is a succulent, enlarged receptacle of the flower, with a number of little achenes (the true fruits) on its surface.

The seed, as we have already observed, is the embryo plant. It consists of one or more seed-leaves or cotyledons, a radicle or young root, and a plumule or young bud. In many cases the skin of the seed encloses nothing more than the three parts of the embryo, as named above; but it sometimes contains, in addition, a quantity of nutrient matter in the form of albumen, starch, oil, gum, or other substance.

Our flowering plants are divided into two main groups, the dicotyledons and the monocotyledons. These terms suggest that the division is based on the nature of the seed, which is really the case, but the groups are characterised by differences in other parts. Thus, the plants which produce seeds with two cotyledons may be known by the nature of the stem, which consists of a central pith, surrounded by wood arranged in one or more rings, and the whole enclosed in an outer epidermis or in a bark. These plants also bear leaves with netted veins, and the parts of the flower are[14] usually in whorls of four or five or multiples of four or five. Those plants whose seeds have only one cotyledon may be known by the absence of a central pith and true bark in the stem, while the wood is arranged in scattered bundles instead of in a ring or rings. They have also, generally, leaves with parallel veins; and the parts of the flower are usually in threes or multiples of three. The following table shows these features at a glance:—

| Dicotyledons | Monocotyledons |

|---|---|

| Embryo with two cotyledons. | Embryo with one cotyledon. |

| Stem with central pith, wood in rings or rings, and bark. | Stem with no central pith, no true bark, and wood not in rings. |

| Leaves with netted veins. | Leaves with parallel veins. |

| Parts of flower usually in fours or fives. | Parts of flower arranged in threes or multiples of three. |

These two great divisions or classes are split up into sub-classes, each embracing a large number of plants with common characters; and the sub-classes are again divided into orders, and the orders into genera.

The student should always endeavour to determine the order to which any flower he finds belongs; and, if possible, the genus and the species. It is certainly a pleasure to be able to call flowers by their names, but at the same time it must be remembered that a vast deal of pleasure may be gained by the study of flowers—their peculiar structure, habits and habitats—even though their names are unknown; and the student who has learnt to recognise these characters, and to discover the relationships that exist between certain flowers of different species, is certainly much more fortunate than the one who knows abundance of names with only a meagre acquaintance with the flowers themselves.

Our table of classification gives the most important distinguishing characters of the classes, sub-classes, and orders, of a very large proportion of our wild flowers, and will enable the reader to determine the natural order of almost every one he sees. In order to show how this table is to be used we will take an imaginary example.

Let us suppose that we find a plant with a square stem; opposite, simple leaves with netted veins; flowers apparently in whorls, in the axils of the leaves; persistent calyx of five united sepals; a lipped corolla, of five united petals, two forming the lower, and three the upper lip; four stamens, attached to the corolla, two[15] longer than the others; a superior, four-lobed ovary; and a fruit of four little nuts; then we proceed to determine the natural order to which it belongs as follows:—

The netted veins of the leaves, and the arrangement of the parts of the flower in whorls of four and five, show us at once that the plant is a dicotyledon. Then, the presence of both calyx and corolla enables us to decide that the plant belongs to Division I. of the dicotyledons—that it belongs to one of the orders 1 to 59. Noting, now, that the corolla is composed of united petals, we are enabled to fix its position in the subdivision I.B, among orders 37 to 59. Next, the superior ovary shows that it must be located in the group I.B 2—orders 44 to 59; and as the stamens are attached to the corolla, we see at once that it is not a member of order 44. Turning now to the Synopsis of the Natural Orders (p. 17), we find that the irregular flowers of this group of orders occur only in 51, 52, 53, 54, and 56. Finally, the square stem, opposite leaves, and character of the fruit, show us that the plant must belong to the order LabiatŠ.

The student should, as far as possible, deal with all flowers in this manner, assigning each one to its proper order; and, if he preserves his specimens for future observation, the names of the orders should always be attached, and the plants arranged accordingly.

Again, should the reader meet with a common flower the name of which was previously known, while he is as yet ignorant as to the order to which it belongs; or, should he find a flower that he can at once identify by means of one of our illustrations; he should not rest satisfied on seeing that the name of the order is given beside the name of the plant, but turn to the synopsis, and note the distinguishing characters which determine the natural position of the plant. In this way he will cultivate the habit of careful observation; will make much more rapid progress in forming an acquaintance with plants in general, and will soon become familiar with those natural affinities which mark, more or less distinctly, a cousinship among the flowers.

To aid the reader in this part of his work we have given the name of the natural order with the name of every plant described; and, where difficulties are likely to occur in the identification of similar common species of the same genus, though perhaps only one member of the genus has been selected for description, a few notes are often included with the object of assisting in the identification of the others.

In our descriptions of wild flowers we do not always repeat those features which are common to the species of their respective orders. These features are, however, of the greatest importance; and thus it is essential that the reader makes himself acquainted with them, by referring to the synopsis of the orders, before noting those characters which are given as being more directly concerned in the determination of the species themselves. Thus, when we describe the Pasque Flower (p. 297) we do not refer to those general characters that apply to all the RanunculaceŠ or Buttercup family, and which may be seen at once by referring to p. 17, but give all those details that are necessary to enable one to distinguish between the Pasque Flower and the other members of the same order.

Dicotyledons

(Leaves with netted veins. Parts of flower generally in fours or fives or multiples of four or five)

Monocotyledons

(Leaves usually with parallel veins. Parts of flower in threes or multiples of three)

1. RanunculaceŠ.—Herbs mostly with alternate leaves and regular flowers. Sepals generally 5, distinct. Petals 5 or more. Stamens 12 or more. Pistil of many distinct carpels. Fruit of many one-seeded achenes. (The Buttercup Family.)

2. BerberidaceŠ.—Shrub with compound spines; alternate, spiny leaves; and pendulous flowers. Sepals 6. Petals 6. Stamens 6. Fruit a berry. (The Berberry Family.)

3. NymphŠaceŠ.—Aquatic plants with floating leaves and solitary flowers. Petals numerous, gradually passing into sepals outwards, and into stamens inwards. Ovary of many cells, with many seeds. (The Water-lily Family.)

4. PapaveraceŠ.—Herbs with a milky sap; alternate leaves without stipules; and regular (generally nodding) flowers. Sepals 2, deciduous. Fruit a capsule. Petals 4. Stamens many. Ovary one-celled, but with many membranous, incomplete partitions. (The Poppy Family.)

5. FumariaceŠ.—Herbs with much divided, exstipulate leaves; and racemes of small irregular, bracteate flowers. Sepals 2 or 0, deciduous. Petals 4, irregular. Stamens 6, in two bundles. Ovary of two carpels, one-celled. (The Fumitory Family.)

6. CruciferŠ.—Herbs with alternate, exstipulate leaves, and racemes of regular flowers. Sepals 4. Petals 4, cruciform. Stamens 6, four longer and two shorter. Ovary one-or two-celled. Fruit a siliqua. (The Cabbage Family.)

7. ResedaceŠ.—Herbs or shrubs with alternate, exstipulate leaves;[18] and spikes of irregular, greenish flowers. Sepals 4 or 5, persistent. Petals 4 to 7, irregular. Stamens many. Ovary of 3 lobes, one-celled. (The Mignonette Family.)

8. CistaceŠ.—Herbs or undershrubs with entire, opposite leaves; and conspicuous, regular flowers. Sepals 3 to 5. Petals 5, twisted in the bud. Stamens many. Ovary of 3 carpels, one-chambered. (The Rock-rose Family.)

9. ViolaceŠ.—Herbs with alternate, stipuled leaves; and axillary, irregular flowers. Sepals 5, persistent. Petals 5, unequal, the lower one prolonged into a spur. Stamens 5. Ovary of three carpels, one-celled. (The Violet Family.)

10. DroseraceŠ.—Small marsh plants with radical, glandular leaves; and cymes of small, white, regular flowers. Sepals 5. Petals 5. Stamens 5 or 10. Ovary of 3 to 5 carpels, one-celled. (The Sundew Family.)

11. PolygalaceŠ.—Herbs with alternate, scattered, exstipulate, simple leaves; and racemes of irregular flowers. Sepals 5, the inner ones resembling petals. Petals 3 to 5, unequal. Stamens 8, in two bundles. Ovary two-celled. Fruit a capsule. (The Milkwort Family.)

12. FrankeniaceŠ.—Herb with opposite, exstipulate leaves; and small, axillary, red, regular flowers. Sepals 4 to 6, united into a tube. Petals 4 to 6. Stamens 4 to 6. Ovary of 2 to 5 carpels, one-celled. (The Sea Heath.)

13. ElatinaceŠ.—Small aquatic herbs, with opposite, stipulate, spathulate leaves; and minute, axillary, red flowers. Sepals, petals and stamens 2 to 5. Fruit a capsule with 2 to 5 valves. (The Waterwort Family.)

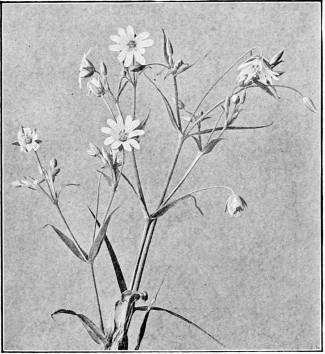

14. CaryophyllaceŠ.—Herbs mostly with jointed stems; opposite, simple leaves; and red or white, regular flowers. Sepals 4 or 5. Petals 4 or 5. Stamens 8 or 10. Styles 2 to 5. Fruit a one-celled capsule, opening at top by teeth. (The Pink Family.)

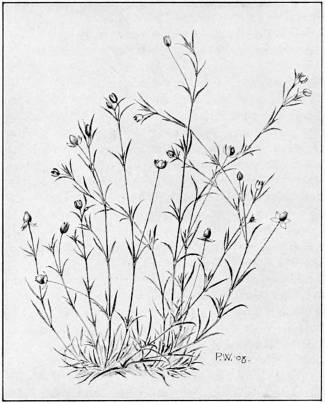

15. LinaceŠ.—Herbs with slender stems; narrow, simple, entire, exstipulate leaves; and cymes of regular flowers. Sepals, petals, stamens, and carpels 4 or 5. Petals twisted in the bud, fugacious (falling early). Carpels each with two ovules. Fruit a capsule of 3 to 5 cells. (The Flax Family.)

16. MalvaceŠ.—Herbs or shrubs with alternate, stipuled leaves; and conspicuous, axillary, regular flowers. Sepals 5. Petals 5, twisted in the bud. Stamens many, united into a tube. Carpels many, each with one ovule. (The Mallow Family.)

17. TiliaceŠ.—Trees with alternate, stipuled, oblique, serrate leaves; a large bract adherent to the flower stalk; and cymes of greenish, regular flowers. Sepals and petals 5. Stamens many. Carpels 5, each with two ovules. (The Linden Family.)

18. HypericaceŠ.—Herbs or shrubs with opposite, simple, exstipulate leaves, often dotted with glands; and cymes of conspicuous yellow, regular flowers. Sepals 4 or 5, with glandular dots. Petals 4 or 5, twisted in the bud. Stamens many, united into several bundles. Carpels 3 to 5, with many ovules. Fruit a capsule with 3 to 5 cells. (The St. John's-wort Family.)

19. AceraceŠ.—Trees with opposite, palmately-lobed leaves; and[19] small, green, regular flowers. Sepals and petals 4 to 9. Stamens 8, on the disc. Fruit a samara. (The Maple Family.)

20. GeraniaceŠ.—Herbs with lobed, generally stipulate leaves; and conspicuous, regular flowers. Sepals 3 to 5, persistent. Petals 3 to 5. Stamens 5 to 10. Carpels 3 to 5, surrounding a long beak. (The Crane's-bill Family.)

21. BalsaminaceŠ.—Herbs with simple, alternate leaves; and axillary, irregular, yellow flowers. Sepals 3 or 5, one forming a wide-mouthed spur. Petals 5, four of which are united in pairs. Stamens 5. Fruit a capsule with five elastic valves. (The Balsam Family.)

22. OxalidaceŠ.—Low herbs, with radical, generally trifoliate leaves; and axillary, regular flowers. Sepals 5. Petals 5, united at the base. Stamens 10. Ovary five-celled, with many ovules. (The Wood Sorrel Family.)

23. CelastraceŠ.—Trees or shrubs, with opposite leaves; and small, regular flowers in axillary cymes. Sepals and petals usually 4. Stamens usually 4, alternating with the petals. Carpels 4. Fruit a fleshy capsule. (Spindle Tree.)

24. RhamnaceŠ.—Shrubs with simple leaves; small, greenish flowers; and berry-like fruit. Sepals, petals, and stamens 4 or 5. Stamens opposite the petals. Ovary superior, three-celled, with one ovule in each cell. (The Buckthorn Family.)

25. LeguminosŠ.—Herbs or shrubs with alternate, stipuled leaves, generally pinnate or ternate, often tendrilled; and papilionaceous (butterfly-like) flowers. Sepals 5, combined. Petals 5, irregular. Stamens generally 10, all, or nine of them united. Ovary superior. Fruit a pod. (The Pea Family.)

26. RosaceŠ.—Trees, shrubs, or herbs with alternate, stipuled leaves; and conspicuous, regular flowers. Sepals 4 or 5. Petals 4 or 5. Stamens many. Carpels 1, 2, 5, or many. (The Rose Family.)

27. OnagraceŠ.—Herbs with mostly entire, simple, exstipulate leaves; and conspicuous, regular flowers. Sepals 2 to 4. Petals 2 to 4, twisted in the bud, or absent. Stamens 2 to 4, or 8. Ovary inferior, with carpels 1 to 6 (usually 4), many-seeded. (The Willow-herb Family.)

28. HaloragiaceŠ.—Aquatic herbs with whorled leaves and minute flowers. Sepals 2 to 4 or absent. Petals 2 to 4 or absent. Stamens 1, 2, 4, or 8. Ovary inferior. Carpels 1 to 4. (The Mare's-tail Family.)

29. LythraceŠ.—Herbs with opposite or whorled, entire leaves; and conspicuous, regular flowers. Sepals, and petals 3 to 6. Stamens generally twice as many as petals. Ovary superior. Carpels 2 to 6. Fruit a many-seeded capsule. (The Loosestrife Family.)

30. TamariscaceŠ.—Shrub with minute, scale-like leaves; and lateral spikes of small, regular flowers. Sepals and petals 4 or 5. Stamens 4 to 10, on the disc. Styles 3. (The Tamarisk.)

31. CucurbitaceŠ.—Rough, climbing herb, with tendrilled, palmately-lobed leaves; greenish, diœcious flowers in axillary racemes; and scarlet berries. Sepals and petals 5, united. Stamens 3. Ovary inferior. Carpels 3. (The White Bryony.)

32. SaxifragaceŠ.—Shrubs and herbs with regular flowers. Sepals[20] and petals 4 or 5. Stamens 4 or 10. Carpels 2 or 4, united. (The Saxifrage Family.)

33. CrassulaceŠ.—Succulent herbs with simple leaves; and small, regular, starry flowers. Sepals, petals, and carpels 3 to 20, usually 5. Stamens twice as many as the petals. Carpels superior, forming follicles. (The Stonecrop Family.)

34. AraliaceŠ.—Climbing shrub with clinging rootlets, evergreen leaves, umbels of yellowish flowers, and black berries. Sepals, petals, stamens, carpels, and seeds 5 each. Ovary inferior. (The Ivy.)

35. CornaceŠ.—Herbs and shrubs with opposite leaves, small flowers, and berry-like fruits. Sepals, petals, and stamens 4 or 5. Ovary inferior. Carpels 2, each with one ovule. (The Dogwood Family.)

36. UmbelliferŠ.—Herbs with mostly compound, pinnate leaves, sheathing at the base; and compound umbels of small, white flowers. Sepals, petals, and stamens 5. Ovary inferior. Fruit of two adhering carpels. (The Parsley Family.)

37. CaprifoliaceŠ.—Shrubs and herbs with opposite leaves, and conspicuous (sometimes irregular) flowers. Sepals and petals 3 to 5. Stamens 4 to 10. Fruit a berry. (The Honeysuckle Family.)

38. RubiaceŠ.—Herbs with whorled leaves; and small, regular flowers. Sepals, petals, and stamens 4 to 6. Carpels 2. (The Bedstraw Family.)

39. ValerianaceŠ.—Herbs with opposite leaves and small (sometimes irregular) flowers. Sepals 3 to 5, often downy. Petals 3 to 5. Stamens 1 or 3. Ovary of three carpels, one-celled. (The Valerian Family.)

40. DipsaceŠ.—Herbs with opposite leaves; and heads of small flowers, mostly blue. Calyx enclosed in a whorl of scaly bracts. Petals 4 or 5. Stamens 4, free. Ovary one-celled and one-seeded. (The Teasel Family.)

41. CompositŠ.—Herbs with heads of small flowers with tubular or strap-shaped corollas. Calyx absent or represented by a whorl of silky hairs (pappus). Stamens 4 or 5, anthers generally united. (The Daisy Family.)

42. CampanulaceŠ.—Herbs with milky sap; alternate, entire, scattered leaves; and usually conspicuous, blue, regular flowers. Sepals, petals, and stamens 5. Ovary of 2 to 8 carpels. (The Bellflower Family.)

43. VacciniaceŠ.—Low (mostly mountainous) shrubs, with scattered, simple, alternate leaves; small drooping, reddish or pink, regular flowers; and edible berries. Sepals, petals, and carpels 4 or 5. Stamens 8 or 10. (The Cranberry Family.)

44. EricaceŠ.—Shrubs or herbs with opposite or whorled, evergreen leaves; and small conspicuous, regular, flowers. Sepals, petals, and carpels 4 or 5. Stamens 5 to 10. (The Heath Family.)

45. AquifoliaceŠ.—Shrub with evergreen, spiny leaves; and[21] small, greenish, regular flowers. Sepals, petals, stamens, and carpels 4 or 5. Fruit berry-like, with one-seeded stones. (The Holly.)

46. OleaceŠ.—Trees or shrubs with opposite leaves; and small, regular flowers. Sepals and petals 4, sometimes absent. Stamens 2. Fruit a berry or a samara. (The Olive Family.)

47. ApocynaceŠ.—Slender, prostrate shrubs, with milky sap; opposite, evergreen, entire leaves; and conspicuous, regular, purple flowers. Sepals, petals, and stamens 5. Corolla salver-shaped. (The Periwinkle Family.)

48. GentianaceŠ.—Bitter herbs with opposite, simple, entire leaves; and regular, conspicuous flowers. Sepals, petals, and stamens 4 to 10. Carpels 2. Fruit a capsule. (The Gentian Family.)

49. ConvolvulaceŠ.—Herbs, generally twining, with alternate, simple leaves (sometimes absent); and mostly conspicuous, regular flowers. Sepals, petals, and stamens 4 or 5. Ovary two-or four-celled. Fruit a four-seeded capsule. (The Bindweed Family.)

50. SolanaceŠ.—Herbs or shrubs with alternate leaves, and axillary cymes of regular flowers. Sepals, petals, and stamens 5. Ovary two-celled. Fruit berry-like or a capsule, many seeded. (The Nightshade Family.)

51. ScrophulariaceŠ.—Herbs with mostly irregular, lipped flowers. Sepals and petals 4 or 5. Stamens 2, or 4, two longer than the others. Carpels 2. Fruit a many-seeded capsule. (The Figwort Family.)

52. OrobanchaceŠ.—Fleshy, brown, parasitic plants, with scattered scale-leaves; and mostly brownish, irregular flowers. Sepals 4 or 5. Petals 5, lipped. Stamens 4, two longer than the others. Carpels 2. Fruit a one-chambered, many-seeded capsule. (The Broom-rape Family.)

53. VerbenaceŠ.—An erect, branched herb, with opposite leaves; and a compound spike of small, irregular flowers. Sepals and petals 5. Corolla lipped. Stamens 4, two longer than the others. Ovary four-celled. Fruit of 4 nutlets. (The Vervain.)

54. LabiatŠ.—Herbs, mostly aromatic, with square stems, opposite leaves, and whorls or cymes of irregular flowers. Sepals and petals 5. Corolla usually lipped. Stamens 4 (rarely 2), two longer than the others. Fruit of 4 one-seeded nutlets. (The Dead Nettle Family.)

55. BoraginaceŠ.—Herbs, mostly rough, with alternate, simple leaves; and spikes of conspicuous, regular flowers. Sepals, petals, and stamens 5. Carpels 2. Fruit of 4 one-seeded nutlets. (The Borage Family.)

56. LentibulariaceŠ.—Insectivorous, marsh herbs, with radical, entire leaves, or much-divided floating leaves with bladders; and conspicuous, irregular flowers. Sepals and petals 5. Corolla usually lipped. Stamens 2. Fruit a one-chambered, many-seeded capsule. (The Butterwort Family.)

57. PrimulaceŠ.—Herbs, mostly with radical leaves; and conspicuous, regular flowers. Sepals, petals, and stamens 4 to 9. Stamens opposite the petals. Ovary one-celled, with free central placenta. Fruit a many-seeded capsule. (The Primrose Family.)

58. PlumbaginaceŠ.—Herbs, mostly maritime, with radical or[22] alternate leaves; and mostly blue, regular flowers. Sepals, petals, and stamens 5. Stamens opposite the petals, and usually free. Carpels 3 to 5. Ovary one-celled and one-seeded. (The Thrift Family.)

59. PlantaginaceŠ.—Herbs with (generally) simple, entire, radical leaves; and spikes of greenish flowers. Sepals, petals, and stamens 4. Corolla scaly. Carpels usually 2 or 4. Fruit a one-to four-chambered capsule. (The Plantain Family.)

Note.—Plants in which calyx or corolla are, or appear to be, absent occur in orders 1, 6, 14, 26, 27, 28, 29, and 32.

60. AmaranthaceŠ.—A smooth, prostrate herb, with scattered, stalked, exstipulate, simple leaves; and small, axillary, green, monœcious flowers. Sepals and stamens 3 to 5. (The Amaranth.)

61. ChenopodiaceŠ.—Herbs with simple, exstipulate leaves, or leafless, jointed stems; and small green flowers. Sepals 3 to 5, persistent. Stamens 1 to 5, opposite the sepals. Fruit indehiscent. (The Goosefoot Family.)

62. PolygonaceŠ.—Herbs with sheathing stipules; alternate, simple leaves; and small flowers. Sepals 3 to 6, green or coloured, usually persistent. Stamens 5 to 8. Fruit indehiscent. (The Dock Family.)

63. EleagnaceŠ.—A shrub with silvery scales; alternate, entire, exstipulate leaves; and inconspicuous, diœcious flowers. Sepals 2 to 4, persistent. Stamens 4. Fruit berry-like. (The Sea Buckthorn.)

64. ThymelaceŠ.—Shrubs with tough inner bark; simple, entire, exstipulate leaves; and conspicuous, perfect, sweet-scented flowers. Sepals 4. Stamens 8. Fruit berry-like. (The Spurge Laurel Family.)

65. LoranthaceŠ.—A green, parasitic, much branched shrub, with opposite, simple, entire leaves; inconspicuous, diœcious flowers; and whitish viscid berries. Sepals and stamens 4. Ovary one-chambered. Berry one-seeded. (The Mistletoe.)

66. AristolochiaceŠ.—Herbs and climbing shrubs, with alternate leaves and perfect flowers. Sepals 2 or 3, sometimes coloured, sometimes lipped. Ovary with 4 to 6 chambers, containing many ovules. (The Birthwort Family.)

67. SantalaceŠ.—A slender, prostrate, root-parasite, with alternate, linear leaves; and inconspicuous, perfect flowers. Sepals and stamens 4 or 5. Ovary one-celled. Fruit dry, one-seeded. (The Bastard Toad-flax.)

68. EmpetraceŠ.—A mountain, evergreen, resinous shrub, with alternate, narrow leaves; and inconspicuous, diœcious flowers. Perianth of 6 scales. Stamens 3. Ovary of 3 to 9 cells, with one ovule in each cell. (The Crowberry.)

69. EuphorbiaceŠ.—Trees, shrubs, or herbs, generally with a milky sap; simple, entire leaves; and small, inconspicuous flowers, sometimes enclosed in calyx-like bracts. Perianth of 3 or 4 parts, or absent. Stamens 1 or many. Fruit separating into 2 or 3 carpels elastically. (The Spurge Family.)

70. UrticaceŠ.—Herbs, often with simple, stinging leaves; and[23] small, green, clustered, unisexual flowers. Stamens 4 or 5, opposite the sepals. Ovary superior, one-celled. Fruit indehiscent. (The Nettle Family.)

71. UlmaceŠ.—Trees with alternate, distichous leaves, and perfect flowers. Perianth of 4 or 5 parts, bell-shaped. Stamens 4 or 5. Ovary superior, with one or two cells. Fruit a thin, one-seeded samara. (The Elm Family.)

72. CupuliferŠ.—Trees or shrubs with alternate, stipuled, simple leaves; and small, green flowers. Perianth of 5 or 6 parts. Stamens 5 to 20. Fruit a nut, enclosed in a tough cupule. (The Oak Family.)

73. BetulaceŠ.—Trees or shrubs with alternate leaves and small flowers. Stamens 1 or more. Fruit small, indehiscent, winged, not enclosed in a cup. (The Birch Family.)

74. SalicaceŠ.—Trees with alternate, simple leaves; and flowers which generally appear before the leaves. Stamens one or more to each scale. Fruit many-seeded, not enclosed in a cup. (The Willow Family.)

75. MyricaceŠ.—A small aromatic shrub, with alternate, simple leaves; and inconspicuous flowers. Stamens 4 to 8. Fruit a drupe. (The Bog Myrtle.)

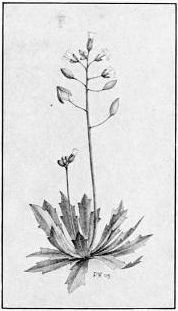

76. ConiferŠ.1—Shrubs or trees with rigid evergreen, linear leaves; and resinous juices. Male flowers in catkins. Female flowers generally in cones. Seeds not enclosed in an ovary. (The Pine Family.)

1 The members of the Pine family do not really belong to the Dicotyledons, although their stems increase in thickness in the same way as those of our other trees and shrubs. They belong to the Gymnosperms (naked-seeded group), in which the seeds are not produced in ovaries; but it is more convenient, for our present purpose, to place them near our other forest trees.

77. OrchidaceŠ.—Herbs mostly with tuberous roots, and conspicuous, irregular, perfect flowers in spikes or racemes. Sepals, petals, and carpels 3. Stamens 1 or 2, united to the style. (The Orchid Family.)

78. IridaceŠ.—Herbs with fleshy, underground stems; narrow leaves; and handsome, irregular, perfect flowers. Perianth of 6 parts. Stamens and carpels 3. Ovary 3-celled. Fruit a many-seeded capsule with three valves. (The Iris Family.)

79. AmaryllidaceŠ.—Herbs with bulbs, narrow leaves, and handsome, regular, perfect flowers. Perianth of 6 parts. Stamens 6. Ovary 3-celled. Fruit a 3-valved capsule. (The Narcissus Family.)

80. HydrocharidaceŠ.—Aquatic herbs, with floating or submerged leaves; and conspicuous, regular, diœcious flowers. Sepals and petals 3. Stamens 3 to 12. Carpels 3 or 6. Fruit a berry. (The Frog-bit Family.)

81. DioscoriaceŠ.—A climbing herb, with broad, glossy leaves; and small, monœcious flowers. Sepals, petals, and carpels 3. Stamens 6. Ovary 3-celled. Fruit a berry. Seeds 6. (The Black Bryony.)

82. LiliaceŠ.—Herbs with mostly narrow leaves, and conspicuous, regular, perfect flowers. Perianth of 6 parts, Stamens 6. Ovary 3-celled. Fruit a berry or capsule. (The Lily Family.)

83. AlismaceŠ.—Aquatic plants with radical, net-veined leaves; and conspicuous, white, perfect flowers. Perianth of 6 parts. Stamens 6 or more. Carpels numerous, and distinct or nearly so. (The Water-plantain Family.)

84. NaidaceŠ.—Aquatic plants with mostly floating or submerged leaves; and inconspicuous flowers. Perianth of 4 to 6 scales, or absent. Stamens and carpels 1 to 6. (The Pond-weed Family.)

85. LemnaceŠ.—Minute floating plants, with green, cellular fronds, rarely flowering. Flowers very small, enclosed in a bract. Stamen 1. Ovary one-celled. Ovules 1 to 7. (The Duckweed Family.)

86. AraceŠ.—Herbs with net-veined, radical leaves; and small flowers on a fleshy spadix enclosed in a leafy sheath. Perianth of 6 parts, or absent. Stamens 1 to 6. Ovary of one to three cells. Fruit berry-like. (The Cuckoo Pint Family.)

87. TyphaceŠ.—Erect marsh plants, with long, narrow leaves; and small monœcious flowers in conspicuous spikes or heads. Perianth absent. Stamens many. Fruit a one-seeded drupe. (The Reed-mace Family.)

88. JuncaceŠ.—Rush-like herbs, with cylindrical or narrow leaves, and small, brown flowers. Perianth membranous, of 6 parts. Stamens 6. Carpels 3. Fruit a 3-valved capsule. (The Rush Family.)

89. CyperaceŠ.—Grassy herbs, with usually solid, triangular stems; and linear leaves, with tubular sheaths. Flowers in spikelets, unisexual or perfect. Stamens 1 to 3. Carpels and stigmas 2 or 3. (The Sedge Family.)

90. GramineŠ.—Grassy herbs, with hollow stems; and linear leaves, with split sheaths. Flowers usually perfect. Stamens usually 3. Stigmas 1 or 2. (The Grass Family.)

Since flowers are the reproductive organs of the plant it seems only natural to suppose that the wonderful variety of colour and form which they exhibit might have some connexion with the processes concerned in the propagation of their respective species, and the more we study the nature of the flowers and observe the methods by which pollen is transferred from stamens to stigmas, the stronger becomes our conviction that the diversities mentioned are all more or less connected with the one great function of reproduction.

This being the case, we propose to devote a short chapter to a simple account of the uses of the parts of a flower, and to the various contrivances on the part of the plant to secure the surest and best means of perpetuating the species.

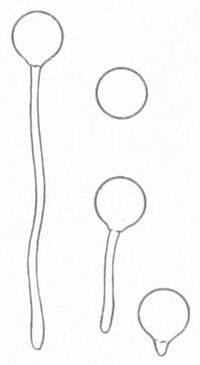

It has already been stated that the stamens produce pollen cells, and that the ovary contains one or more ovules. As soon as the anthers are mature, they open and set free the pollen cells they contained. A stigma is said to be mature when it exposes a sticky surface to which pollen cells may adhere, and on which these cells will grow. When a pollen cell has been transferred to such a stigma, it is nourished by the fluid secreted by the latter, and sends out a slender, hollow filament (the pollen tube) which immediately begins to descend through the stigma, and through the style, if any, till it reaches the ovary.

Pollen Cells throwing out their Tubes.

Should the reader desire to watch the growth of the pollen tubes, he can easily do so by shaking some pollen cells (preferably large ones, such as those of some lilies) on to a solution of sugar, and watching them at intervals with the aid of a lens. In the course of a few hours the pollen[26] tubes will be seen to protrude, and these eventually grow to a considerable length.

In order that the ovules of a flower may develop into seeds, it is necessary that they become impregnated by pollen from the anthers of the same species, and this is brought about in the following manner: The pollen cells having been transferred by some means to the mature stigma, they adhere to the surface of the latter, and, deriving their nourishment from the secretion of the stigmatic cells, as above described, proceed to throw out their tubes. These tubes force their way between the cells of the stigma and style, and enter the ovary. Each tube then finds its way to one of the ovules, which it enters by means of a minute opening in its double coat called the micropyle, penetrates the embryo-sac, and reaches the ovum or egg-cell. The ovule is now impregnated or fertilised, and the result is that the ovum divides and subdivides into more and more cells till at last an embryo plant is built up. The ovule has thus become a seed, and its further development into a mature plant depends on its being transferred to a suitable soil, with proper conditions as to heat and moisture.

If the flower concerned is a perfect one, and the ovules are impregnated by pollen from its own anthers, it is said to be self-fertilised; but if the pollen cells that fertilise the ovules have been transferred from a distinct flower, it is said to be cross-fertilised.

Now, it has been observed that although self-fertilisation will give rise to satisfactory results in some instances, producing seeds which develop into strong offspring, cross-fertilisation will, as a rule, produce better seeds. In fact, self-fertilisation is not at all common among flowers, and the pollen has frequently no effect unless it has been transferred from another flower. In a few cases it has been found that the pollen even acts as a poison when it is deposited on the stigma of the same flower, causing it to shrivel up and die. In many instances the structure and growth of the flower is such that self-pollination is absolutely impossible; and where it is possible the seedlings resulting from the process are often very weak.

It has already been hinted that the wonderful variety of form and colour exhibited by flowers has some connexion with this important matter of the transfer of pollen, and the reader who is really interested in the investigation of the significance of this great diversity will find it a most charming study to search into the[27] advantages (to the flower) of the different peculiarities presented, especially if he endeavours to confirm his conclusions by direct observations of the methods by which the pollen cells are distributed to the stigmas.

Pollen cells are usually distributed either by the agency of the wind or by insects; and it is generally easy to determine, by the nature of the flower itself, which is the method peculiar to its species.

A wind-pollinated flower is generally very inconspicuous. It produces no nectar, which forms the food of such a large number of insects, and has no gaudy perianth, nor does it emit any odour such as would be likely to attract these winged creatures. Its anthers generally shed an abundance of pollen, to compensate for the enormous loss naturally entailed in the wasteful process of wind-distribution, and the pollen is so loosely attached that it is carried away by the lightest breeze. Further, the anthers are never protected from the wind, but protrude well out of the flower; and the stigma or stigmas, which are also exposed, have a comparatively large area of sticky surface, and are often hairy or plumed in such a manner that they form effectual traps for the capture of the floating pollen cells.

An insect-pollinated flower, on the other hand, has glands (nectaries) for the production of nectar, and its perianth is usually of such a conspicuous nature that it serves as a signal to attract the insects to the feast. (In some instances the individual flowers are very small, but these are generally produced in such clusters that they become conspicuous through their number.) Often it emits a scent which assists in guiding the insects to their food. Its stamens are generally so well protected by the perianth that the pollen is not likely to be removed except by the insects that enter the flower; and the supply of pollen is usually not so abundant as in the wind-pollinated species, for the insects, travelling direct from flower to flower, convey the cells with greater economy. The stigmas, too, are generally smaller, and are situated in such a position that, when mature, they are rubbed by that portion of the insect's body which is already dusted with pollen.

As we watch the nectar-feeding insects at work, we not only observe that the flowers they visit possess the general characters given above as common to the insect-pollinated species, but also that, in many instances, the structure of the flower is such that the transfer of pollen from anthers to stigma could only be accomplished by the particular kind of insect which it feeds. Various contrivances are[28] also adopted by many flowers to attract the insects which are most useful to them, and to exclude those species which would deprive them of nectar and pollen without aiding in the work of pollination. Thus, some flowers are best pollinated by the aid of certain nocturnal insects, which they attract at night by the expansion of their pale-coloured corollas and by the emission of fragrant perfumes. These close their petals by day in order to economise their stores and protect their parts from injury while their helpers are at rest. Others require the help of day-flying insects: these are expanded while their fertilisers are on the wing, and sleep throughout the night.

We do not propose to give detailed accounts of the various stratagems by which flowers secure the aid of insects in this short chapter. Several examples are given in connexion with the descriptions of flowers in subsequent pages, but a few typical instances, briefly outlined here, will give the reader some idea of features which should be observed as flowers are being examined.

In many flowers the anthers and the stigma are not mature at the same time, and consequently self-pollination is quite impossible. With these it often happens that the anthers and stigma alternately occupy the same position, so that the same part of the body of an insect which becomes dusted with pollen in one flower rubs against the stigma of another.

Other flowers, such as the Forget-me-not, in which both stamens and stigma are ripe together, project their stigmas above the stamens at first, in order that an insect from another flower might touch the stigma before it reaches the stamens, and thus cross-pollinate them; and their stamens are afterwards raised by the lengthening of the corolla until they touch the stigma. Thus the flowers attempt to secure cross-pollination; but, failing this, pollinate themselves.

In the Common Arum or Cuckoo Pint, described on p. 106, we have an example of a flower of peculiar construction, surrounded by a very large bract in which insects are imprisoned and fed until the anthers are mature, and then set free in order that they might carry the pollen to another flower of which the stigmas are ripe.

Sometimes the flowers of the same species assume two or three different forms as far as the lengths of the stamens and pistils are concerned, the anthers of one being of just the same height as the stigma of another, so that the pollen from the former will dust that portion of the body of the insect which rubs against the latter[29] Examples are to be found among the Primulas, and in the Purple Loosestrife, both of which are described in their place.

In some flowers the stamens are irritable, rising in such a manner as to strike the insects that visit them; and in these cases the anthers almost invariably deposit pollen on that portion of the insect's body which is most likely to come in contact with the stigma of the next flower visited. Again, in Sages, the anthers are so arranged that they are made to swing, as on a see-saw, to exactly the same end.

These few examples will suffice to show that the structure and conformation of flowers are subservient to the one great purpose of securing the most suitable means of the distribution of pollen, and the student who recognises and studies the various forms of flowers in this connexion will find his work in the field doubly interesting.

Many plants have stems which grow to a considerable length, and which are at the same time too weak to support the plants in the erect position. A considerable number of these show no tendency to assume an upward direction, but simply trail along the surface of the ground, often producing root fibres at their nodes to give them a firmer hold on the soil and to absorb additional supplies of water and mineral food. Some, however, grow in the midst of the shrubs and tall herbage of thickets and hedgerows, or in some other position in which it becomes necessary to strive for a due proportion of light, and such plants would stand but a small chance in the struggle for existence if they did not develop some means of securing a favourable position among their competitors.

These latter are collectively spoken of as climbing plants; but it is interesting to note that in their seedling stage they are all erect, and it is only after they reach a certain height that they commence to assume some definite habit by which they obtain the necessary support, or to develop special organs by which they can cling to objects near them.

Some climbers produce no special organs for the purpose of fastening themselves to surrounding objects, but trust entirely to the wandering and more or less zig-zag nature of their feeble stems, and thus reach the open light merely by a process of interweaving, as in the case of the Hedge Bedstraw (Galium mollugo). Others adopt this same method of interweaving, but at the same time develop some kind of appendages to give them additional support. Thus, the Rough Water Bedstraw (G. uliginosum), which sometimes reaches a height of four or five feet, has recurved bristles all along its slender stem, and these serve as so many little hooks, holding the plant securely on to the neighbouring rank herbage of the marsh[31] or swamp in which it grows, while the rigid leaves further assist by catching in the angles of surrounding stems.

Another good example is to be seen in the common Goose-grass or Cleavers (G. aparine) of our hedgerows, which also reaches a height of four or five feet, and clings very effectually by means of the hooked bristles of its stems and leaves.

The Marsh Speedwell (Veronica scutellata), though it grows to a height of only one foot, is too weak to stand erect without support, and it has quite a novel method of securing the aid of the plants among which it grows. Its two topmost leaves at first stand erect over the terminal bud, so that they are easily pushed through the spaces in the surrounding herbage as the stem lengthens. They then diverge, and even turn slightly downwards, thus forming two supporting arms, the holding power of which is further increased by the down-turned teeth of their margins. This process is repeated by the new pairs of leaves formed at the growing summit of the stem, with the result that the plant easily retains the erect position.

Prickles of the Wild Rose.

The Wild Roses and Brambles growing in the hedgerows support themselves among the other shrubby growths by the interlacing of their stems, but are also greatly aided by the abundance of prickles with which these stems are armed. The prickles, even if erect, would afford considerable assistance in this respect; but it may be observed that they are generally directed downwards, and often very distinctly curved in this direction, and so serve to suspend the weak stems at numerous points.