The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Mesmerist's Victim, by Alexandre Dumas This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Mesmerist's Victim Author: Alexandre Dumas Translator: Henry Llewellyn Williams Release Date: May 11, 2013 [EBook #42690] [Last updated: September 17,2014] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MESMERIST'S VICTIM *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| Many spelling and punctuation errors have been corrected. A list of the etext transcriber’s spelling corrections follows the text. Consistent archaic spellings have not been changed. (courtseyed, hight, gallopped, befel, spirted, drily, abysm, etc.) |

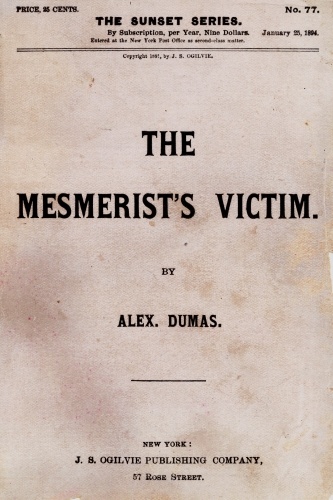

| PRICE, 25 CENTS. | No. 77. | |

| THE SUNSET SERIES. | ||

| By Subscription, per Year, Nine Dollars. | January 25, 1894. | |

| Entered at the New York Post-Office as second-class matter. | ||

| Copyright 1892, by J. S. OGILVIE. | ||

BY

ALEX. DUMAS.

———

NEW YORK:

J. S. OGILVIE PUBLISHING COMPANY,

57 ROSE STREET.

Chapter: I. , II. , III. , IV. , V. , VI. , VII. , VIII. , IX. , X. , XI. , XII. , XIII. , XIV. , XV. , XVI. , XVII. , XVIII. , XIX. , XX. , XXI. , XXII. , XXIII. , XXIV. , XXV. , XXVI. , XXVII. , XXVIII. , XXIX. , XXX. , XXXI. , XXXII. , XXXIII. , XXXIV. , XXXV. , XXXVI. , XXXVII. , XXXVIII. , XXXIX. , XL. , XLI. , XLII. , XLIII.

A WONDERFUL OFFER!

———

70 House Plans for $1.00.

———

If you are thinking about building

a house don’t fail to get the new

book

PALLISER’S

AMERICAN

ARCHITECTURE,

containing 104 pages, 11×14 inches in size, consisting of large 9×12 plate pages giving plans, elevations, perspective views, descriptions, owners’ names, actual cost of construction (no guess work), and instructions How to Build 70 Cottages, Villas, Double Houses, Brick Block Houses, suitable for city suburbs, town and country, houses for the farm, and workingmen’s homes for all sections of the country, and costing from $300 to $6,500, together with specifications, form of contract, and a large amount of information on the erection of buildings and employment of architects, prepared by Palliser, Palliser & Co., the well-known architects.

This book will save you hundreds of dollars.

There is not a Builder, nor anyone intending to build or otherwise interested, that can afford to be without it. It is a practical work, and the best, cheapest and most popular book ever issued on Building. Nearly four hundred drawings.

It is worth $5.00 to anyone, but we will send it bound in paper cover, by mail, post-paid for only $1.00; bound in handsome cloth, $2.00. Address all orders to

J. S. OGILVIE PUBLISHING CO.,

Lock Box 2767. 57 Rose Street, New York.

A HISTORICAL ROMANCE

BY ALEX. DUMAS.

Author of “Monte Cristo,” “The Three Musketeers Series,” “Chicot

the Jester Series,” etc.

TRANSLATED FROM THE LATEST PARIS EDITION.

BY

HENRY LLEWELLYN WILLIAMS.

NEW YORK:

J. S. OGILVIE PUBLISHING COMPANY,

57 ROSE STREET.

———

Entered according to act of Congress in the year 1892, by A. E. Smith &

Co, in the office

of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

———

ON the thirteenth of May, 1770, Paris celebrated the wedding of the Dauphin or Prince Royal Louis Aguste, grandson of Louis XV. still reigning, with Marie-Antoinette, Archduchess of Austria.

The entire population flocked towards Louis XV. Place, where fireworks were to be let off. A pyrotechnical display was the finish to all grand public ceremonies, and the Parisians were fond of them although they might make fun.

The ground was happily chosen, as it would hold six thousand spectators. Around the equestrian statue of the King, stands were built circularly to give a view of the fireworks, to be set off at ten or twelve feet elevation.

The townsfolk began to assemble long before seven o’clock when the City Guard arrived to keep order. This duty rather belonged to the French Guards, but the Municipal government had refused the extra pay their Commander, Colonel, the Marshal Duke Biron, demanded, and these warriors in a huff were scattered in the mob, vexed and quarrelsome. They sneered loudly at the tumult, which they boasted they would have quelled with the pike-stock or the musket-butt if they had the ruling of the gathering.

The shrieks of the women, squeezed in the press, the wailing of the children, the swearing of the troopers, the grumbling of the fat citizens, the protests of the cake and candy merchants whose goods were stolen, all prepared a petty uproar preceding the deafening one which six hundred thousand souls were sure to create when collected. At eight at evening, they produced a vast picture, like one after Teniers, but with French faces.

About half past eight nearly all eyes were fastened on the scaffold where the famous Ruggieri and his assistants were putting the final touches to the matches and fuses of the old pieces. Many large compositions were on the frames. The grand bouquet, or shower of stars, girandoles and squibs, with which such shows always conclude, was to go off from a rampart, near the Seine River, on a raised bank.

As the men carried their lanterns to the places where the pieces would be fired, a lively sensation was raised in the throng, and some of the timid drew back, which made the whole waver in line.

Carriages with the better class still arrived but they could not reach the stand to deposit their passengers. The mob hemmed them in and some persons objected to having the horses lay their heads on their shoulder.

Behind the horses and vehicles the crowd continued to increase, so that the conveyances could not move one way or another. Then were seen with the audacity of the city-bred, the boys and the rougher men climb upon the wheels and finally swarm upon the footman’s board and the coachman’s box.

The illumination of the main streets threw a red glare on the sea of faces, and flashed from the bayonets of the city guardsmen, as conspicuous as a blade of wheat in a reaped field.

About nine o’clock one of these coaches came up, but three rows of carriages were before the stand, all wedged in and covered with the sightseers. Hanging onto the springs was a young man, who kicked away those who tried to share with him the use of this locomotive to cleave a path in the concourse. When it stopped, however, he dropped down but without letting go of the friendly spring with one hand. Thus he was able to hear the excited talk of the passengers.

Out of the window was thrust the head of a young and beautiful girl, wearing white and having lace on her sunny head.

“Come, come, Andrea,” said a testy voice of an elderly man within to her, “do not lean out so, or you will have some rough fellow snatch a kiss. Do you not see that our coach is stuck in this mass like a boat in a mudflat? we are in the water, and dirty water at that; do not let us be fouled.”

“We can’t see anything, father,” said the girl, drawing in her head: “if the horse turned half round we could have a look through the window, and would see as well as in the places reserved for us at the governor’s.”

“Turn a bit, coachman,” said the man.

“Can’t be did, my lord baron,” said the driver; “it would crush a dozen people.”

“Go on and crush them, then!”

“Oh, sir,” said Andrea.

“No, no, father,” said a young gentleman beside the old baron inside.

“Hello, what baron is this who wants to crush the poor?” cried several threatening voices.

“The Baron of Taverney Redcastle—I,” replied the old noble, leaning out and showing that he wore a red sash crosswise.

Such emblems of the royal and knightly orders were still respected, and though there was grumbling it was on a lessening tone.

“Wait, father,” said the young gentleman, “I will step out and see if there is some way of getting on.”

“Look out, Philip,” said the girl, “you will get hurt. Only hear the horses neighing as they lash out.”

Philip Taverney, Knight of Redcastle, was a charming cavalier and, though he did not resemble his sister, he was as handsome for a man as she for her sex.

“Bid those fellows get out of our way,” said the baron, “so we can pass.”

Philip was a man of the time and like many of the young nobility had learnt ideas which his father of the old school was incapable of appreciating.

“Oh, you do not know the present Paris, father,” he returned. “These high-handed acts of the masters were all very well formerly; but they will hardly go down now, and you would not like to waste your dignity, of course.”

“But since these rascals know who I am—— ”

“Were you a royal prince,” replied the young man smiling, “they would not budge for you, I am afraid; at this moment, too, when the fireworks are going off.”

“And we shall not see them,” pouted Andrea.

“Your fault, by Jove—you spent more than two hours over your attire,” snarled the baron.

“Could you not take me through the mob to a good spot on your arm, brother?” asked she.

“Yes, yes, come out, little lady,” cried several voices; for the men were struck by Mdlle. Taverney’s beauty: “you are not stout, and we will make room for you.”

Andrea sprang lightly out of the vehicle without touching the steps.

“I think little of the crackers and rockets, and I will stay here,” growled the baron.

“We are not going far, father,” responded Philip.

Always respectful to the queen called Beauty, the mob opened before the Taverneys, and a good citizen made his wife and daughter give way on a bench where they stood, for the young lady. Philip stood by his sister, who rested a hand on his shoulder. The young man who had “cut behind” the carriage, had followed them and he looked with fond eyes on the girl.

“Are you comfortable, Andrea?” said the chevalier; “see what a help good looks are!”

“Good looks,” sighed the strange young man; “why, she is lovely, very lovely. She is lovelier here, in Parisian costume, than when I used to see her on their country place, where I was but Gilbert the humble retainer on my lord Baron’s lands.’”

Andrea heard the compliment; but she thought it came not from an acquaintance so far as a dependent could be the acquaintance of a young lady of title, and she believed it was a common person who spoke.

Infinitely proud, she heeded it no more than an East Indian idol troubles itself about the adorer who places his tribute at its feet.

Hardly were the two young Taverneys established on and by the bench than the first rockets serpentined towards the clouds, and a loud “Oh!” was roared by the multitude henceforth absorbed in the sight.

Andrea did not try to conceal her impressions in her astonishment at the unequalled sight of a population cheering with delight before a palace of fire. Only a yard from her, the youth who had named himself as Gilbert, gazed on her rather than at the show, except because it charmed her. Every time a gush of flame shone on her beautiful countenance, he thrilled; he could fancy that the general admiration sprang from the adoration which this divine creature inspired in him who idolized her.

Suddenly, a vivid glare burst and spread, slanting from the river: it was a bomshell exploding fiercely, but Andrea merely admired the gorgeous play of light.

“How splendid,” she murmured.

“Goodness,” said her brother, disquieted, “that shot was badly aimed for it shoots almost on the level instead of taking an upward curve. Oh, God, it is an accident! Come away—it is a mishap which I dreaded. A stray cracker has set fire to the powder on the bastion. The people are trampling on each other over there to get away. Do you not hear those screams—not cheers but shrieks of distress. Quick, quick, to the coach! Gentlemen, gentlemen, please let us through.”

He put his arms around his sister’s slender waist, to drag her in the direction of her father. Also made uneasy by the clamor, the danger being evident though not distinguished yet by him, he put his head out of the window to look for his dear ones.

It was too late!

The final display of fifteen thousand rockets-burst, darting off in all directions, and chasing the spectators like those squibs exploded in the bull-fighting ring to stir up the bull.

At first surprised but soon frightened, the people drew back without reflection. Before this invincible retreat of a hundred thousand, another mass as numerous gave the same movement when squeezed to the rear. The wooden work at the bastion took fire; children cried, women tossed their arms; the city guardsmen struck out to quiet the brawlers and re-establish order by violence.

All these causes combined to drive the crowd like a waterspout to the corner where Philip of Taverney stood. Instead of reaching the baron’s carriage as he reckoned, he was swept on by the resistless tide, of which no description can give an idea. Individual force, already doubled by fear and pain, was increased a hundredfold by the junction of the general power.

As Philip dragged Andrea away, Gilbert was also carried off by the human current: but at the corner of Madeline Street, a band of fugitives lifted him up and tore him away from Andrea, in spite of his struggles and yelling.

Upon the Taverneys charged a team of runaway horses. Philip saw the crowd part; the smoking heads of the animals appeared and they rose on their haunches for a leap. He leaped, too, and being a cavalry officer, captain in the Dauphiness’s Dragoons, knew how to deal with them. He caught the bit of one and was lifted with it.

Andrea saw him flung and fall; she screamed, threw up her arms, was buffeted, reeled, and in an instant was tossed hence alone, like a feather, without the strength to offer resistance.

Deafening calmor, more dreadful than shouts of battle, the horses neighing, the clatter of the vehicles on the pavement cumbered with the crippled, and livid glare of the burning stands, the sinister flashing of swords which some of the soldiers had drawn, in their fury and above the bloody chaos, the bronze statue gleaming with the light as it presided over the carnage—here was enough to drive the girl mad.

She uttered a despairing cry; for a soldier in cutting a way for himself in the crowd had waved the dripping blade over her head. She clasped her hands like a shipwrecked sailor as the last breaker swamps him, and gasping “God have mercy” fell.

One had heard this final, supreme appeal. It was Gilbert who had been snaking his way up to her. Though the same rush bent him down, he rose, seized the soldier by the throat and upset him.

Where he felled him, lay the white-robed form: he lifted it up with a giant’s strength.

When he felt this beautiful body on his heart, though it might be a corpse, a ray of pride illuminated his face.

The sublime situation made him the sublimation of strength and courage extreme; he dashed with his burden into the torrent of men. This would have broken a hole through a wall. It sustained him and carried them both. He just touched the ground with his feet, but her weight began to tell on him. Her heart beat against his.

“She is saved,” he said, “and I have saved her,” he added, as the mass brought up against the Royal Wardrobe Building, and he was sheltered in the angle of masonry.

But looking towards the bridge over the Seine, he did not see the twenty thousand wretches on his right, mutilated, welded together, having broken through the barrier of the carriages and mixed up with them as the drivers and horses were seized with the same vertigo.

Instinctively they tried to get to the wall against which the closest were mashed.

This new deluge threatened to grind those who had taken refuge here by the Wardrobe building, with the belief they had escaped. Maimed bodies and dead ones piled up by Gilbert. He had to back into the recess of the gateway, where the weight made the walls crack.

The stifled youth felt like yielding; but collecting all his powers by a mighty effort, he enclasped Andrea with his arms, applying his face to her dress as if he meant to strangle her whom he wished to protect.

“Farewell,” he gasped as he bit her robe in kissing it.

His eyes glancing about in an ultimate call to heaven, were offered a singular vision.

A man was standing on a horseblock, clinging by his right hand to an iron ring sealed in the wall: while with his left he seemed to beckon an army in flight to rally.

He was a tall dark man of thirty, with a figure muscular but elegant. His features had the mobility of Southerners’, strangely blending power and subtlety. His eyes were piercing and commanding.

As the mad ocean of human beings poured beneath him he cast out a word or a cabalistic token. On these, some individual in the throng was seen to stop, fight clear and make his way towards the beckoner to fall in at his rear. Others, called likewise, seemed to recognize brothers in each other, and all lent their hands to catch still more of the swimmers in this tide of life. Soon this knot of men were formed into the head of a breakwater, which divided the fugitives and served to stay and stem the rush.

At every instant new recruits seemed to spring out of the earth at these odd words and weird gestures, to form the backers of this wondrous man.

Gilbert nerved himself. He felt that here alone was safety, for here was calm and power.

A last flicker of the burning staging, irradiated this man’s visage and Gilbert uttered an outcry of surprise.

“I know who that is,” he said, “he visited my master down at Taverney. It is Baron Balsamo. Oh, I care not if I die provided she lives. This man has the power to save her.”

In perfect self-sacrifice, he raised the girl up in both hands and shouted:

“Baron Balsamo, save Andrea de Taverney!”

Balsamo heard this voice from the depths; he saw the white figure lifted above the matted beings; he used the phalanx he had collected to cover his charge to the spot. Seizing the girl, still sustained by Gilbert though his arms were weakening, he snatched her away, and let the crowd carry them both afar.

He had not time to turn his head.

Gilbert had not the breath to utter a word. Perhaps, after having Andrea aided, he would have supplicated assistance for himself; but all he could do was clutch with a hand which tore a scrap of the dress of the girl. After this grasp, a last farewell, the young man tried no longer to struggle, as though he were willing to die. He closed his eyes and fell on a heap of the dead.

TO great tempests succeeds calm, dreadful but reparative.

At two o’clock in the morning a wan moon was playing through the swift-driving white clouds upon the fatal scene where the merry-makers had trampled and buried one another in the ditches.

The corpses stuck out arms lifted in prayers and legs broken and entangled, while the clothes were ripped and the faces livid.

Yellow and sickening smoke, rising from the burning platforms on Louis XV. Place, helped to give it the aspect of a battlefield.

Over the bloody and desolate spot wandered shadows which were the robbers of the dead, attracted like ravens. Unable to find living prey, they stripped the corpses and swore with surprise when they found they had been forestalled by rivals. They fled, frightened and disappointed as soldier’s bayonets at last appeared, but among the long rows of the dead, robbers and soldiers were not the solely moving objects.

Supplied with lanterns prowlers were busy. They were not only curious, but relatives and parents and lovers who had not had their dear ones come home from the sightseeing. They came from the remotest parts for the horrible news had spread over Paris, mourning as if a hurricane had passed over it, and anxiety was acted out in these searches.

It was muttered that the Provost of Paris had many corpses thrown into the river from his fears at the immense number lost through his want of foresight. Hence those who had ferreted about uselessly, went to the river and stood in it knee-deep to stare at the flow; or they stole with their lanterns into the by-streets where it was rumored some of the crippled wretches had crept to beg help and at least flee the scene of their misfortune.

At the end of the square, near the Royal Gardens, popular charity had already set up a field hospital. A young man who might be identified as a surgeon by the instruments by his side, was attending to the wounded brought to him. While bandaging them he said words rather expressing hatred for the cause of their injuries than pity for the effect. He had two helpers, robust reporters, to whom he kept on shouting:

“Let me have the poor first. You can easily pick them out for they will be badly dressed and most injured.”

At these words, continually croaked, a young gentleman with pale brow, who was searching among the bodies with a lantern in his hand, raised his head.

A deep gash on his forehead still dropped red blood. One of his hands was thrust between two buttons of his coat to support his injured arm; his perspiring face betrayed deep and ceaseless emotion.

Looking sadly at the amputated limbs which the operator appeared to regard with professional pleasure, he said:

“Oh, doctor, why do you make a selection among the victims?”

“Because,” replied the surgeon, raising his head at this reproach, “no one would care for the poor if I did not, and the rich will always find plenty to look after them. Lower your light and look along the pavement and you will find a hundred poor to one rich or noble. In this catastrophe, with their luck which will in the end tire heaven itself, the aristocrats have paid their tax as usual, one per thousand.”

The gentleman held up his lantern to his own face.

“Am I only one of my class?” he queried, without irritation, “a nobleman who was lost in the throng, where a horse kicked me in the face and my arm was broken by my falling into a ditch. You say the rich and noble are looked after—have I had my wounds dressed?”

“You have your mansion and your family doctor; go home, for you are able to walk.”

“I am not asking your help, sir; I am seeking my sister, a fair girl of sixteen, no doubt killed, alas! albeit she is not of the lower classes. She wore a white dress and a necklace with a cross. Though she has a residence and a doctor, for pity’s sake! answer me if you have seen her?”

“Humanity guides me, my lord,” said the young surgeon with feverish vehemence proving that such ideas had long been seething within his bosom; “I devote myself to mankind, and I obey the law of her who is my goddess when I leave the aristocrat on his deathbed to run and relieve the suffering people. All the woes happened here are derived from the upper class; they come from your abuses, and usurpation; bear therefore the consequences. No lord, I have not seen your sister.”

With this blasting retort, the surgeon resumed his task. A poor woman was brought to him over whose both legs a carriage had rolled.

“Behold,” he pursued Philip with a shout, “is it the poor who drive their coaches about on holidays so as to smash the limbs of the rich?”

Philip, belonging to the new race who sided with Làfayette, had more than once professed the opinions which stung him from this youth: their application fell on him like chastisement. With breaking heart, he turned aloof on his mournful exploration, but soon they could hear his tearful voice calling:

“Andrea, Andrea!”

Near him hurried an elderly man, in grey coat, cloth stockings, and leaning on a cane, while with his left hand he held a cheap lantern made of a candle surrounded by oiled paper.

“Poor young man,” he sighed on hearing the gentleman’s wail and comprehending his anguish, “Forgive me,” he said, returning after letting him pass as though he could not let such great sorrow go by without endeavoring to give some alleviation, “forgive my mingling grief with yours, but those whom the same stroke strikes ought to support one another. Besides, you may be useful to me. As your candle is nearly burnt out you must have been seeking for some time, and so know a good many places. Where do they lie thickest?”

“In the great ditch more than fifty are heaped up.”

“So many victims during a festival?”

“So many?—I have looked upon a thousand dead—and have not yet come upon my sister.”

“Your sister?”

“She was lost in that direction. I have found the bench where we were parted. But of her not a trace. I began to search at the bastion. The mob moved towards the new buildings in Madeleine Street. There I hunted, but there were great fluctuations. The stream rushed thither, but a poor girl would wander anywhere, with her crazed head, seeking flight in any direction.”

“I can hardly think that she would have stemmed the current. We two may find her together at the corner of the streets.”

“But who are you after—your son?” questioned Philip.

“No, an adopted youth, only eighteen, who was master of his actions and would come to the festival. Besides, one was so far from imagining this horrid catastrophe. Your candle is going out—come with me and I will light you.”

“Thanks, you are very kind, but I shall obstruct you.”

“Fear nothing, for I must be seeking, too. Usually the lad comes home punctually,” continued the old man, “but I had a forerunner last evening. I was sitting up for him at eleven when my wife had the rumor from the neighbors of the miseries of this rejoicing. I waited a couple of hours in hopes that he would return, but then I felt it would be cowardly to go to sleep without news.”

“So we will hunt over by the houses,” said the nobleman.

“Yes, as you say the crowd went there and would certainly have carried him along. He is from the country and knows no more the way than the streets. This may be the first time he came to this place.”

“My sister is country-bred also.”

“Shocking sight,” said the old man, before a mound of the suffocated.

“Still we must search,” said the chevalier, resolutely holding out the lantern to the corpses. “Oh, here we are by the Wardrobe Stores—ha! white rags—my sister wore a white dress. Lend me your light, I entreat you, sir.”

“It is a piece of a white dress,” he continued, “but held in a young man’s hand. It is like that she wore. Oh, Andrea!” he sobbed as if it tore up his heart.

The old man came nearer.

“It is he,” he exclaimed, “Gilbert!”

“Gilbert? do you know our farmer’s son, Gilbert, and were you seeking him?”

The old man took the youth’s hand, it was icy cold. Philip opened his waistcoat and found that his heart was quiet. But the next instant he cried: “No, he breathes—he lives, I tell you.”

“Help! this way, to the surgeon,” said the old man.

“Nay, let us do what we can for him for I was refused help when I spoke to him just now.”

“He must take care of my dear boy,” said the old man.

And taking Gilbert between him and Taverney, they carried him towards the surgeon, who was still croaking:

“The poor first—bring in the poor, first.”

This maxim was sure to be hailed with admiration from a group of lookers-on.

“I bring a man of the people,” retorted the old man hotly, feeling a little piqued at this exclusiveness.

“And the women next, as men can bear their hurt better,” proceeded the character.

“The boy only wants bleeding,” said Gilbert’s friend.

“Ho, ho, so it is you, my lord, again?” sneered the surgeon, perceiving Taverney.

The old gentleman thought that the speech was addressed to him and he took it up warmly.

“I am not a lord—I am a man of the multitude—I am Jean Jacques Rousseau.”

The surgeon uttered an exclamation of surprise and said as he waved the crowd back imperiously:

“Way for the Man of Nature—the Emancipator of Humanity—the Citizen of Geneva! Has any harm befallen you?”

“No, but to this poor lad.”

“Ah, like me, you represent the cause of mankind,” said the surgeon.

Startled by this unexpected eulogy, the author of the “Social contract” could only stammer some unintelligible words, while Philip Taverney, seized with stupefaction at being in face of the famous philosopher, stepped aside.

Rousseau was helped in placing Gilbert on the table.

Then Rousseau gave a glance to the surgeon whose succor he invoked. He was a youth of the patient’s own age, but no feature spoke of youth. His yellow skin was wrinkled like an old man’s, his flaccid eyelid covered a serpent’s glance, and his mouth was drawn one side like one in a fit. With his sleeves tucked up to the elbow and his arms smeared with blood, surrounded by the results of the operation he seemed rather an enthusiastic executioner than a physician fulfilling his sad and holy mission.

But the name of Rousseau seemed to influence him into laying aside his ordinary brutality. He softly opened Gilbert’s sleeve, compressed the arm with a linen ligature and pricked the vein.

“We shall pull him through,” he said, “but great care must be taken with him for his chest was crushed in.”

“I have to thank you,” said Rousseau, “and praise you—not for the exclusion you make on behalf of the poor, but for your devotion to the afflicted. All men are brothers.”

“Even the rich, the noble, the lofty?” queried the surgeon, with a kindling look in his sharp eye under the drooping lid.

“Even they, when they are in suffering.”

“Excuse me, but I am like you a Switzer, having been born at Neuchatel; and so I am rather democratic.”

“My fellow-countryman? I should like to know your name.”

“An obscure one, a modest man who devotes his life to study until like yourself he can employ it for the common-weal. I am Jean Paul Marat.”

“I thank you, Marat,” said Rousseau, “but in enlightening the masses on their rights, do not excite their revengeful feelings. If ever they move in that direction, you might be amazed at the reprisals.”

“Ah,” said Marat with a ghastly smile, “if it should come in my time—should I see that day—— ”

Frightened at the accent, as a traveler by the mutterings of a coming storm, Rousseau took Gilbert in his arms and tried to carry him away.

“Two willing friends to help Citizen Rousseau,” shouted Marat; “two men of the lower order.”

Rousseau had plenty to choose among; he took two lusty fellows who carried the youth in their arms.

“Take my lantern,” said the author to Taverney as he passed him: “I need it no longer.”

Philip thanked him and went on with his search.

“Poor young gentleman,” sighed Rousseau, as he saw him disappear in the thronged streets.

He shuddered, for still rang over the bloody field he surgeon’s shrill voice shouting:

“Bring in the poor—none but the poor! Woe to the rich, the noble and the high-born!”

WHILE the thousand casualties were precipitated upon each other, Baron Taverney escaped all the dangers by some miracle.

An old rake, and hardened in cynicism, he seemed the least likely to be so favored, but he maintained himself in the thick of a cluster by his skill and coolness, while incapable of exerting force against the devouring panic. His group, bruised against the Royal Storehouse, and brushed along the square railings, left a long trail of dead and dying on both flanks but, though decimated, its centre was kept out of peril.

As soon as these lucky men and women scattered upon the boulevard, they yelled with glee. Like them, Taverney found himself out of harm’s reach. During all the journey, the baron had thought of nobody but his noble self. Though not emotional, he was a man of action, and in great crises such characters put Caesar’s adage into practice—Act for yourself. We will not say he was selfish but that his attention was limited.

But soon as he was free on the main street, escaped from death and re-entering life, the old baron uttered a cry of delight, followed by another of pain.

“My daughter,” he said, in sorrow, though it was not so loud as the other.

“Poor dear old man,” said some old women, flocking round ready to condole with him, but still more to question.

He had no popular inclinations. Ill at ease among the gossips he made an effort to break the ring, and to his credit got off a few steps towards the square. But they were but the impulse of parental love, never wholly dead in a man; reason came to his aid, and stopped him short.

He cheered himself with the reasoning that if he, a feeble old man had struggled through, Andrea, on the strong arm of her brave and powerful brother, must have likewise succeeded. He concluded that the two had gone home, and he proceeded to their Paris lodging, in Coq-Heron street.

But he was scarcely within twenty paces of the house, on the street leading to a summerhouse in the gardens, where Philip had induced a friend to let them dwell, when he was hailed by a girl on the threshold. This was a pretty servant maid, who was jabbering with some women.

“Have you not brought Master Philip and Mistress Andrea?” was her greeting.

“Good heavens, Nicole, have they not come home?” cried the baron, a little startled, while the others were quivering with the thrill which permeated all the city from the exaggerated story of the first fugitives spreading.

“Why, no, my lord, no one has seen them.”

“They could not come home by the shortest road,” faltered the baron, trembling with spite at his pitiful line of reasoning falling to pieces.

There he stood, in the street, with Nicole whimpering, and an old valet, who had accompanied the Taverneys to town, lifting his hands to the sky.

“Oh, here comes Master Philip,” ejaculated Nicole, with inexpressible terror, for the young man was alone.

He ran up through the shades of evening, desperate, calling out as soon as he saw the gathering at the house door:

“Is my sister here?”

“We have not seen her—she is not here,” said Nicole. “Oh, heavens, my poor young mistress!” she sobbed.

“The idea of your coming back without her!” said the baron with anger the more unfair as we have shown how he quitted the scene of the disaster.

By way of answer he showed his bleeding face and his arm broken and hanging like a dead limb by his side.

“Alas, my poor Andrea,” sighed the baron, falling, seated on a stone bench by the door.

“But I shall find her, dead or alive,” replied the young man gloomily.

And he returned to the place with feverish agitation. He would have lopped off his useless arm, if he had an axe, but as it was, he tucked the hand into his waistcoat for an improvised sling.

It was thus we saw him on the square, where he wandered part of the night. As the first streaks of dawn whitened the sky, he turned homeward, though ready to drop. From a distance he saw the same familiar group which had met his eyes on the eve. He understood that Andrea had not returned, and he halted.

“Well?” called out the baron, spying him.

“Has she not returned? no news—no clew?” and he fell, exhausted, on the stone bench, while the older noble swore.

At this juncture, a hack appeared at the end of the street, lumbered up, and stopped in front of the house. As a female head appeared at the window, thrown back as if in a faint, Philip, recognizing it, leaped that way. The door opened, and a man stepped out who carried Andrea de Taverney in his arms.

“Dead—they bring her home dead,” gasped Philip, falling on his knees.

“I do not think so, gentlemen,” said the man who bore Andrea, “I trust that Mdlle. de Taverney is only fainted.”

“Oh, the magician,” said the baron, while Philip uttered the name of “the Baron of Balsamo.”

“I, my lord, who was happy enough to spy Mdlle. de Taverney in the riot, near the Royal wardrobe storehouse.”

But Philip passed at once from joy to doubt and said:

“You are bringing her home very late, my lord.”

“You will understand my plight,” replied Balsamo without astonishment. “I was unaware of the address of your sister, though your father calls me a magician, kindly remembering some little incidents occurring at your country-seat. So I had her carried by my servants to the residence of the Marchioness of Savigny, a friend who lives near the Royal Stables. Then this honest fellow—Comtois,” he said, waving a footman in the royal livery to come forward, “being in the King’s household and recognizing the young lady from her being attendant of the Dauphiness, gave me this address. Her wonderful beauty had made him remark her one night when the royal coach left her at this door. I bade him get upon the box, and I have the honor to bring to you, with all the respect she merits—the young lady, less ill than she may appear.”

He finished by placing the lady with the utmost respect in the hands of Nicole and her father. For the first time the latter felt a tear on his eyelid, and he was astonished as he let it openly run down his wrinkled cheek.

“My lord,” said Philip, presenting the only hand he could use to Balsamo, “You know me and my address. Give me a chance to repay the services you have done me.”

“I have merely accomplished duty,” was the reply. “I owed you for the hospitality you once favored me at Taverney.” He took a few paces to depart, but retracing them, he added: “I ask pardon; but I was forgetting to leave the precise address of Marchioness Savigny; she lives in Saint Honore Street, near the Feuillant’s Monastery. This is said in case Mdlle. de Taverney should like to pay her a visit.”

In this explanation, exactness of details and accumulation of proofs, the delicacy touched the young lord and even the old one.

“My daughter owes her life to your lordship,” said the latter.

“I am proud and happy in that belief,” responded Balsamo.

Followed by Comtois, who refused the purse Philip offered, he went to the carriage and was gone.

Simultaneously, as if the departure made the swooning of Andrea cease, she opened her eyes. For a while she was dumb, and stunned, and her look was frightened.

“Heavens, have we but had her half restored—with her reason gone?” said Philip.

Seeming to comprehend the words, Andrea shook her head. But she remained mute, as if in ecstasy. Standing, one of her arms was levelled in the direction in which Balsamo had disappeared.

“Come, come, it is high time our worry was over,” said the baron. “Help your sister indoors my son.”

Between the young gentleman and Nicole, Andrea reached the rear house, but walked like a somnambulist.

“Philip—father!” she uttered as speech returned to her at last.

“She knows us,” exclaimed the young knight.

“To be sure I know you; but what has taken place?”

Her eyes closed in a blessed sleep this time, and Nicole carried her into her bedroom.

On going to his own room, Captain Philip found a doctor whom the valet Labrie had sent for. He examined the injured arm, not broken but dislocated, and set the bone. Still uneasy about his sister, he took the medical man to her bedside. He felt her pulse, listened to her breathing and smiled.

“Her slumber is calm and peaceful as a child’s,” he said. “Let her sleep on, young sir, there is nothing more to do.”

The baron was sound asleep already assured about his children on whom were built the ambitious schemes which had lured him to the capital.

MORE fortunate than Andrea, Gilbert had in lieu of an ordinary practitioner, a light of medical science to attend to his ails. The eminent Dr Jussieu, a friend of Rousseau’s, though allied to the Court, happened to call in the nick to be of service. He promised that the young man would be on his legs in a week.

Moreover, being a botanist like Rousseau, he proposed that on the coming Sunday they should give the youth a walk with them in the country, out Marly way. Gilbert might rest while they gathered the curious plants.

With this prospect to entice him, the invalid returned rapidly to health.

But while Rousseau believed that his ward was well, and his wife Therese told the gossips that it was due to the skill of the celebrated Dr. Jussieu, Gilbert was running the worst danger ever befalling his obstinacy and perpetual dreaming.

Gilbert was the son of a farmer on the land of Baron Taverney. The master had dissipated his revenue and sold his principal to play the rake in Paris. When he returned to bring up his son and daughter in poverty in the dilapidated manor house, Gilbert was a hanger-on, who fell in love with Nicole as a stepping-stone to becoming infatuated with her mistress. As at the fireworks, the youth never thought of anything but this mad love.

From the attic of Rousseau’s house he could look down on the garden where the summerhouse stood in which Andrea was also in convalescence.

He did not see her, only Nicole carrying broth as for the invalid. The back of the little house came to the yard of Rousseau’s in another street.

In this little garden old Taverney trotted about, taking snuff greedily as if to rouse his wits—that was all Gilbert saw.

But it was enough to judge that a patient was indoors, not a dead woman.

“Behind that screen in the room,” he mused, “is the woman whom I love to idolatry. She has but to appear to thrill my every limb for she holds my existence in her hand and I breathe but for us two.”

Merged in his contemplation he did not perceive that in another window of an adjoining house in his street, Plastriere Street, a young woman in the widow’s weeds, was also watching the dwelling of the Taverneys. This second spy knew Gilbert, too, but she took care not to show herself when he leaned out of the casement as to throw himself on the ground. He would have recognized her as Chon, the sister of Jeanne, Countess Dubarry, the favorite of the King.

“Oh, how happy they are who can walk about in that garden,” raved the mad lover, with furious envy, “for there they could hear Andrea and perhaps see her in her rooms. At night, one would not be seen while peeping.”

It is far from desire to execution. But fervid imaginations bring extremes together; they have the means. They find reality amid fancies, they bridge streams and put a ladder up against a mountain.

To go around by the street would be no use, even if Rousseau had not locked in his pet, for the Taverneys lived in the rear house.

“With these natural tools, hands and feet,” reasoned Gilbert, “I can scramble over the shingles and by following the gutter which is rather narrow, but straight, consequently the shortest path from one point to another, I will reach the skylight next my own. That lights the stairs, so that I can get out. Should I fall, they will pick me up, smashed at her feet, and they will recognize me, so that my death will be fine, noble, romantic—superb!

“But if I get in on the stairs I can go down to the window over the yard and jump down a dozen feet where the trellis will help me to get into her garden. But if that worm-eaten wood should break and tumble me on the ground that would not be poetic, but shameful to think of! The baron will say I came to steal the fruit and he will have his man Labrie lug me out by the ear.

“No, I will twist these clotheslines into a rope to let me down straight and I will make the attempt to-night.”

From his window, at dark, Gilbert was scanning the enemy’s grounds, as he qualified Taverney’s house-lot, when he spied a stone coming over the garden-wall and slapping up against the house-wall. But though he leaned far out he could not discry the flinger of the pebble.

What he did see was a blind on the ground floor open warily and the wide-awake head of the maid Nicole show itself. After having scrutinized all the windows round, Nicole came out of doors and ran to the espalier on which some pieces of lace were drying.

The stone had rolled on this place and Gilbert had not lost sight of it. Nicole kicked it when she came to it and kept on playing football with it till she drove it under the trellis where she picked it up under cover of taking off the lace. Gilbert noticed that she shucked the stone of a piece of paper, and he concluded that the message was of importance.

It was a letter, which the sly wench opened, eagerly perused and put in her pocket without paying any more heed to the lace.

Nicole went back into the house, with her hand in her pocket. She returned with a key which she slipped under the garden gate, which would be out in the street beside the carriage-doorway.

“Good, I understand,” thought the young man: “it is a love letter. Nicole is not losing her time in town—she has a lover.”

He frowned with the vexation of a man who supposed that his loss had left an irreparable void in the heart of the girl he jilted, and discovered that she had filled it up.

“This bids fair to run counter to my plans,” thought he, trying to give another turn to his ill-humor. “I shall not be sorry to learn what happy mortal has succeeded me in the good graces of Nicole Legay.”

But Gilbert had a level mind in some things; he saw that the knowledge of this secret gave him an advantage over the girl, as she could not deny it, while she scarcely suspected his passion for the baron’s daughter, and had no clew to give body to her doubts.

The night was dark and sultry, stifling with heat as often in early spring. From the clouds it was a black gulf before Gilbert, through which he descended by the rope. He had no fear from his strength of will. So he reached the ground without a flutter. He climbed the garden wall but as he was about to descend, heard a step beneath him.

He clung fast and glanced at the intruder.

It was a man in the uniform of a corporal of the French Guards.

Almost at the same time, he saw Nicole open the house backdoor, spring across the garden, leaving it open, and light and rapid as a shepherdess, dart to the greenhouse, which was also the soldier’s destination. As neither showed any hesitation about proceeding to this point, it was likely that this was not the first appointment the pair had kept there.

“No, I can continue my road,” reasoned Gilbert; “Nicole would not be receiving her sweetheart unless she were sure of some time before her, and I may rely on finding Mdlle. Andrea alone. Andrea alone!”

No sound in the house was audible and only a faint light was to be seen.

Gilbert skirted the wall and reached the door left open by the maid. Screened by an immense creeper festooning the doorway, he could peer into an anteroom, with two doors; the open one he believed to be Nicole’s. He groped his way into it, for it had no light.

At the end of a lobby, a glazed door, with muslin curtains on the other side, showed a glimmer. On going up this passage, he heard a feeble voice.

It was Andrea’s.

All Gilbert’s blood flowed back to the heart.

THE voice which made answer to the girl’s was her brother Philip’s. He was anxiously asking after her health.

Gilbert took a few steps guardedly and stood behind one of those half-columns carrying a bust which were the ornaments in pairs to doorways of the period. Thus in security, he looked and listened, so happy that his heart melted with delight; yet so frightened that it seemed to shrink up to a pin’s head.

He saw Andrea lounging on an invalid-chair, with her face turned towards the glazed door, a little on the jar. A small lamp with a large reflecting shade placed on a table heaped with books, showed the only recreation allowed the fair patient, and illumined only the lower part of her countenance.

Seated on the foot of the chair, Philip’s back was turned to the watcher; his arm was still in a sling.

This was the first time the lady sat up and that her brother was allowed out. They had not seen each other since the dreadful night; but both had been informed of the respective convalescence. They were chatting freely as they believed themselves alone and that Nicole would warn them if any one came.

“Then you are breathing freely,” said Philip.

“Yes, but with some pain.”

“Strength come back, my poor sister?”

“Far from it, but I have been able to get to the window two or three times. How nice the open air is—how sweet the flowers—with them it seems that one cannot die. But I am so weak from the shock having been so horrid. I can only walk by hanging on to the furniture; I should fall without support.”

“Cheer up, dear; the air and flowers will restore you. In a week you will be able to pay a visit to the Dauphiness who has kindly asked after you, I hear.”

“I hope so, for her Highness has been good to me; to you in promoting you to be captain in her guards, and to father, who was induced by her benevolence to leave our miserable country house.

“Speaking of your miraculous escape,” said Philip, “I should like to know more about the rescue.”

Andrea blushed and seemed ill at ease. Either he did not remark it or would not do so.

“I thought you knew all about it,” said she; “father was perfectly satisfied.

“Of course, dear Andrea, and it seemed to me that the gentleman behaved most delicately in the matter. But some points in the account seemed obscure—I do not mean suspicious.”

“Pray explain,” said the girl with a virgin’s candor.

“One point is very out of the way—how you were saved. Kindly relate it.”

“Oh, Philip,” she said with an effort, “I have almost forgotten—I was so frightened.”

“Never mind—tell me what you do remember.”

“You know, brother, that we were separated within twenty paces of the Royal Wardrobe Storehouse? I saw you dragged away towards the Tuileries Gardens, while I was hurled into Royale Street. Only for an instant did I see you, making desperate efforts to return to me. I held out my arms to you and was screaming, ‘Philip!’ when I was suddenly wrapped in a whirlwind, and whisked up towards the railings. I feared that the current would dash me up against the wall and shatter me. I heard the yells of those crushed against the iron palings; I foresaw my turn coming to be ground to rags. I could reckon how few instants I had to live, when—half dead, half crazed, as I lifted eyes and arms in a last prayer to heaven, I saw the eyes sparkle of a man who towered over the multitude and it seemed to obey him.”

“You mean Baron Balsamo, I suppose?”

“Yes, the same I had seen at Taverney. There he struck me with uncommon terror. The man seems supernatural. He fascinates my sight and my hearing; with but the touch of his finger he would make me quiver all over.”

“Continue, Andrea,” said the chevalier, with darkening brow and moody voice.

“This man soared over the catastrophe like one whom human ills could not attain. I read in his eyes that he wanted to save me and something extraordinary went on within me: shaken, bruised, powerless and nearly dead though I was, to that man I was attracted by an invincible, unknown and mysterious force, which bore me thither. I felt arms enclasp me and urge me out of this mass of welded flesh in which I was kneaded—where others choked and gasped I was lifted up into air. Oh, Philip,” said she with exaltation, “I am sure it was the gaze of that man. I grasped at his hand and I was saved.”

“Alas,” thought Gilbert, “I was not seen by her though dying at her feet.”

“When I felt out of danger, my whole life having been centred in this gigantic effort or else the terror surpassed my ability to contend—I fainted away.”

“When do you think this faint came on?”

“Ten minutes after we were rent asunder, brother.”

“That would be close on Midnight,” remarked the Knight of Red Castle. “How then was it you did not return home until three? You must forgive me questions which may appear to you ridiculous but they have a reason to me, dear Andrea.”

“Three days ago I could not have replied to you,” she said, pressing his hand, “but, strange as it may be, I can see more clearly now. I remember as though a superior will made me do so.”

“I am waiting with impatience. You were saying that the man took you up in his arms?”

“I do not recall that clearly,” answered Andrea, blushing. “I only know that he plucked me up out of the crowd. But the touch of his hand caused me the same shock as at Taverney, and again I swooned or rather I slept, for it was a sleep that was good.”

Gilbert devoured all the words, for he knew that so far all was true.

“On recovering my senses, I was in a richly furnished parlor. A lady and her maid were by my side, but they did not seem uneasy. Their faces were benevolently smiling. It was striking half-past twelve.”

“Good,” said the knight, breathing freely. “Continue, Andrea, continue.”

“I thanked the lady for the attentions she was giving, but, knowing in what anxiety you must all be, I begged to be taken home at once. They told me that the Count—for they knew our Baron Balsamo as Count Fenix, had gone back to the scene of the accident, but would return with his carriage and take me to our house. Indeed, about two o’clock, I heard carriage wheels and felt the same warning shiver of his approach. I reeled and fell on a sofa as the door opened; I barely could recognize my deliverer as the giddiness seized me. During this unconsciousness I was put in the coach and brought here. It is all I recall, brother.”

“Thank you, dear,” said Philip, in a joyful voice; “your calculations of the time agree with mine. I will call on Marchioness Savigny and personally thank her. A last word of secondary import. Did you notice any familiar face in the excitement? Such as little Gilbert’s, for instance?”

“Yes, I fancy I did see him a few paces off, as you and I were driven apart,” said Andrea, recollecting.

“She saw me,” muttered Gilbert.

“Because, when I was seeking you, I came across the boy.”

“Among the dead?” asked the lady with the shade of assumed interest which the great take in their inferiors.

“No, only wounded, and I hope he will come round. His chest was crushed in.”

“Ay, against hers,” thought Gilbert.

“But the odd part of it was that I found in his clenched hand a rag from your dress, Andrea,” pursued Philip.

“Odd, indeed; but I saw in this Dance of Death such a series of faces, that I can hardly say whether his figured truly there or not, poor little fellow!”

“But how do you account for the scrap in his grip?” pressed the captain.

“Good gracious! nothing more easy,” rejoined the girl with tranquillity greatly contrasting with the eavesdropper’s frightful throbbing of the heart. “If he were near me and he saw me lifted up, as I stated, by the spell of that man, he might have clutched at my skirts to be saved as the drowning snatch at a straw.”

“Ugh,” grumbled Gilbert, with gloomy contempt for this haughty explanation, “what ignoble interpretation of my devotion! How wrongly these aristocrats judge us people. Rousseau is right in saying that we are worth more than they—our heart is purer and our arms stronger.”

At that he heard a sound behind him.

“What, is not that madcap Nicole here?” asked Baron Taverney, for it was he who passed by Gilbert hiding and entered his daughter’s room.

“I dare say she is in the garden,” replied his daughter, the latter with a quiet proving that she had no suspicion of the listener; “good evening, papa.”

The old noble took an armchair.

“Ha, my children, it is a good step to Versailles when one travels in a hackney coach instead of one of the royal carriages. I have seen the Dauphiness, though, who sent for me to learn about your progress.”

“I knew that and told her Royal Highness so. She is good enough to promise to call her to her side when she sets up her establishment in the Little Trianon Palace which is being fitted up to her liking.”

“I at court?” said Andrea timidly.

“Not much of a court; the Dauphiness has quiet tastes and the Prince Royal hates noise and bustle. They will live domestically at Trianon. But judging what the Austrian princess’s humor is, I wager that as much will be done in the family circle as at official assemblies. The princess has a temper and the Dauphin is deep, I hear.”

“Make no mistake, sister, it will still be a court,” said Captain Philip, sadly.

“The court,” thought Gilbert with intense rage and despair, “a hight I cannot scale—an abyss into which I cannot hurl myself! Andrea will be lost to me!”

“We have neither the wealth to allow us to inhabit that palace, nor the training to fit us for it,” replied the girl to her father. “What would a poor girl like me do among those most brilliant ladies of whom I have had a glimpse? Their splendor dazzled me, while their wit seemed futile though sparkling. Alas, brother, we are obscure to go amid so much light!”

“What nonsense!” said the baron, frowning. “I cannot make out why my family always try to bemean what affects me! obscure—you must be mad, miss! A Taverney Redcastle, obscure! who should shine if not you, I want to know? Wealth? we know what wealth at court is—the crown is a sun which creates the gold—it does the gilding, and it is the tide of nature. I was ruined—I become rich, and there you have it. Has not the King money to offer his servitors? Am I to blush if he provides my son with a regiment and gives my daughter a dowry? or an appanage for me, or a nice warrant on the Treasury—when I am dining with the King and I find it under my plate?”

“No, no, only fools are squeamish—I have no prejudices. It is my due and I shall take it. Don’t you have any scruples, either. The only matter to debate is your training. You have the solid education of the middle class with the more showy one of your own; you paint just such landscapes as the Dauphiness doats upon. As for your beauty, the King will not fail to notice it. As for conversation, which Count Artois and Count Provence like—you will charm them. So you will not only be welcome but adored. That is the word,” concluded the cynic, rubbing his hands and laughing so unnaturally that Philip stared to see if it were a human being.

But, taking Andrea’s hand as she lowered her eyes, the young gentleman said:

“Father is right; you are all he says, and nobody has more right to go to Versailles Palace.”

“But I would be parted from you,” remonstrated Andrea.

“Not at all,” interrupted the baron; “Versailles is large enough to hold all the Taverneys.”

“True, but the Trianon is small,” retorted Andrea, who could be proud and willful.

“Trianon is large enough to find a room for Baron Taverney,” returned the old nobleman, “a man like me always finds a place”—meaning “can find a place. Any way, it is the Dauphiness’s order.”

“I will go,” said Andrea.

“That is good. Have you any money, Philip?” asked the old noble.

“Yes, if you want some; but if you want to offer me it, I should say that I have enough as it is.”

“Of course, I forgot you were a philosopher,” sneered the baron. “Are you a philosopher, too, my girl, or do you need something?”

“I should not like to distress you, father.”

“Oh, luck has changed since we left Taverney. The King has given me five hundred louis—on account, his Majesty said. Think of your wardrobe, child.”

“Oh, thank you, papa,” said Andrea, joyously.

“Oho, going to the other extreme now! A while ago, you wanted for nothing—now you would ruin the Emperor of China. Never mind, for fine dresses become you, darling.”

With a tender kiss, he opened the door leading into his own room, and disappeared, saying:

“Confound that Nicole for not being in to show me a light!”

“Shall I ring for her, father?”

“No, I shall knock against Labrie, dozing on a chair. Good night, my dears.”

“Good night, brother,” said Andrea as Philip also stood up: “I am overcome with fatigue. This is the first time, I have been up since my accident.”

The gentleman kissed her hand with respect mixed with his affection always entertained for his sister and he went through the corridor, almost brushing against Gilbert.

“Never mind Nicole—I shall retire alone. Good bye, Philip.”

A SHIVER ran through the watcher as the girl rose from her chair. With her alabaster hands she pulled out her hairpins one by one while the wrapper, slipping down upon her shoulders, disclosed her pure and graceful neck, and her arms, carelessly arched over her head, threw out the lower curve of the body to the advantage of the exquisite throat, quivering under the linen.

Gilbert felt a touch of madness and was on the verge of rushing forward, yelling:

“You are lovely, but you must not be too proud of your beauty since you owe it to me—it was I saved your life!”

Suddenly a knot in the corset string irritated Andrea who stamped her foot and rang the bell.

This knell recalled the lover to reason. Nicole had left the door open so as to run back. She would come.

He wanted to dart out of the house, but the baron had closed the other doors as he came along. He was forced to take refuge in Nicole’s room.

From there he saw her hurry in to her mistress, assist her to bed and retire, after a short chat, in which she displayed all the fawning of a maid who wishes to win her forgiveness for delinquency.

Singing to make her peace of mind be believed, she was going through on the way to the garden when Gilbert showed himself in a moonbeam.

She was going to scream but taking him for another, she said, conquering her fright:

“Oh, it is you—what rashness!”

“Yes, it is I—but do not scream any louder for me than the other,” said Gilbert.

“Why, whatever are you doing here?” she challenged, knowing her fellow-dependent at Taverney. “But I guess—you are still after my mistress. But though you love her, she does not care for you.”

“Really?”

“Mind that I do not expose you and have you thrown out,” she said in a threatening tone.

“One may be thrown out, but it will be Nicole to whom stones are tossed over the wall.”

“That is nothing to the piece of our mistress’s dress found in your hand on Louis XV Square, as Master Philip told his father. He does not see far into the matter yet, but I may help him.”

“Take care, Nicole, or they may learn that the stones thrown over the wall are wrapped in love-letters.”

“It is not true!” Then recovering her coolness, she added: “It is no crime to receive a love-letter—not like sneaking in to peep at poor young mistress in her private room.”

“But it is a crime for a waiting-maid to slip keys under garden doors and keep tryst with soldiers in the greenhouse!”

“Gilbert, Gilbert!”

“Such is the Nicole Virtue! Now, assert that I am in love with Mdlle. Andrea and I will say I am in love with my playfellow Nicole and they will believe that the sooner. Then you will be packed off. Instead of going to the Trianon Palace with your mistress, and coqueting with the fine fops around the Dauphiness, you will have to hang around the barracks to see your lover the corporal of the Guards. A low fall, and Nicole’s ambition ought to have carried her higher. Nicole, a dangler on a guardsman!”

And he began to hum a popular song:

“In the French Guards my sweetheart marches!”

“For pity’s sake, Gilbert, do not eye me thus—it alarms me.”

“Open the door and get that swashbuckler out of the way in ten minutes when I may take my leave.”

Subjugated by his imperious air, Nicole obeyed. When she returned after dismissing the corporal, her first lover was gone.

Alone in his attic, Gilbert cherished of his recollections solely the picture of Andrea letting down her fine tresses.

INDIFFERENT to everything since he had learnt of Andrea’s going soon to the court, Gilbert had forgotten the excursion of Rousseau and his brother botanist on Sunday. He would have preferred to pass the day at his garret window, watching his idol.

Rousseau had not only taken special pains over his attire, but arrayed Gilbert in the best, though Therese had thought overalls and a smockfrock quite good enough to wander in the woods, picking up weeds.

He was not wrong for Dr. Jussieu came in his carriage, powdered, pommaded and freshened up like springtime: Indian satin coat, lilac taffety vest, extremely fine white silk stockings and polished gold buckled shoes composed his botanist’s outfit.

“How gay you are!” exclaimed Rousseau.

“Not at all, I have dressed lightly to get over the ground better.”

“Your silk hose will never stand the wet.”

“We will pick our steps. Can one be too fine to court Mother Nature?”

The Genevan Philosopher said no more—an invocation to Nature usually shutting him up. Gilbert looked at Jussieu with envy. If he were arrayed like him, perhaps Andrea would look at him.

An hour after the start, the party reached Bougival, where they alighted and took the Chestnut Walk. On coming in sight of the summerhouse of Luciennes, where Gilbert had been conducted by Mdlle. Chon when he was picked up by her, a poor boy on the highway, he trembled. For he had repaid her succor by fleeing when she had wished to make a buffoon of him as a peer to Countess Dubarry’s black boy, Zamore.

“It is nine o’clock,” observed Dr. Jussieu, “suppose we have breakfast?”

“Where? did you bring eatables in your carriage?”

“No, but I see a kiosk over there where a modest meal may be had. We can herborize as we walk there.”

“Very well, Gilbert may be hungry. What is the name of your inn?”

“The Trap.”

“How queer!”

“The country folks have droll ideas. But it is not an inn; only a shooting-box where the gamekeepers offer hospitality to gentlemen.”

“Of course you know the owner’s name?” said Rousseau, suspicious.

“Not at all: Lady Mirepoix or Lady Egmont—or—it does not matter if the butter and the bread are fresh.”

The good-humored way in which he spoke disarmed the philosopher who besides had his appetite whetted by the early stroll. Jussieu led the march, Rousseau followed, gleaning, and Gilbert guarded the rear, thinking of Andrea and how to see her at Trianon Palace.

At the top of the hill, rather painfully climbed by the three botanists, rose one of those imitation rustic cottages invented by the gardeners of England and giving a stamp of originality to the scene. The walls were of brick and the shelly stone found naturally in mosaic patterns on the riverside.

The single room was large enough to hold a table and half-a-dozen chairs. The windows were glazed in different colors so that you could by selection view the landscape in the red of sunset, the blue of a cloudy day or the still colder slate hue of a December day.

This diverted Gilbert but a more attractive sight was the spread on the board. It drew an outcry of admiration from Rousseau, a simple lover of good cheer, though a philosopher, from his appetite being as hearty as his taste was modest.

“My dear master,” said Jussieu, “if you blame me for this feast you are wrong, for it is quite a mild set-out—— ”

“Do not depreciate your table, you gormand!”

“Do not call it mine!”

“Not yours? then whose—the brownies, the fairies?” demanded Rousseau, with a smile testifying to his constraint and good nature at the same time.

“You have hit it,” answered the doctor, glancing wistfully to the door.

Gilbert hesitated.

“Bless the fays for their hospitality,” said Rousseau, “fall on! they will be offended at your holding back and think you rate their bounty incomplete.”

“Or unworthy you gentlemen,” interrupted a silvery voice at the summerhouse door, where two pretty women presented themselves arm in arm.

With smiles on their lips, they waved their plump hands for Jussieu to moderate his salutations.

“Allow me to present the Author Rousseau to your ladyship, countess,” said the latter. “Do you not know the lady?”

Gilbert did, if his teacher did not, for he stared and, pale as death, looked for an exit.

“It is the first time we meet,” faltered the Citizen of Geneva.

“Countess Dubarry!” explained the other botanist.

His colleague started as though on a redhot plate of iron.

Jeanne Dubarry, favorite of King Louis X. was a lovely woman, just of the right plumpness to be a material Venus; fair, with light hair but dark eyes she was witching and delightful to all men who prefer truth to fancy in feminine beauty.

“I am very happy,” she said “to see and welcome under my roof one of the most illustrious thinkers of the era.”

“Lady Dubarry,” stammered Rousseau, without seeing that his astonishment was an offense. “So it is she who gives the breakfast?”

“You guess right, my dear philosopher,” replied Jussieu, “she and her sister, Mdlle. Chon, who at least is no stranger to Friend Gilbert.”

“Her sister knows Gilbert?”

“Intimately,” rejoined the impudent girl with the audacity which respected neither royal ill-humor nor philosopher’s quips. “We are old boon companions—are you already forgetful of the candy and cakes of Luciennes and Versailles?”

This shot went home; Rousseau dropped his arms. Habituated in his conceit to think the aristocratic party were always trying to seduce him from the popular side, he saw traitors and spies in everybody.

“Is this so, unhappy boy?” he asked of Gilbert, confounded. “Begone, for I do not like those who blow hot and cold with the same breath.”

“But I ran away from Luciennes where I was locked up, and I must have preferred your house, my guide, my friend, my philosopher!”

“Hypocrisy!”

“But, M. Rousseau, if I wanted the society of these ladies, I should go with them now?”

“Go where you like! I may be deceived once but not twice. Go to this lady, good and amiable—and with this gentleman,” he added pointing to Jussieu, amazed at the philosopher’s rebuke to the royal pet, “he is a lover of nature and your accomplice—he has promised you fortune and assistance and he has power at court.”

He bowed to the women in a tragic manner, unable to contain himself, and left the pavillion statelily, without glancing again at Gilbert.

“What an ugly creature a philosopher is,” tranquilly said Chon, watching the Genevan stumble down the hill.

“You can have anything you like,” prompted Jussieu to Gilbert who kept his face buried in his hands.

“Yes, anything, Gilly,” added the countess, smiling on the returned prodigal.

Raising his pale face, and tossing back the hair matted on his forehead, he said in a steady voice:

“I should be glad to be a gardener at Trianon Palace.”

Chon and the countess glanced at each other, and the former touched her sister’s foot while she winked broadly. Jeanne nodded.

“If feasible, do it,” she said to Jussieu.

Gilbert bowed with his hand on his heart, overflowing with joy after having been drowned with grief.

WHEN Louis XIV. built Versailles and perceived the discomfort of grandeur, he granted it was the sojourneying-place for a demi-god but no home for a man. So he had the Trianon constructed to be able to draw a free breath at leisure moments.

But the sword of Achilles, if it tired him, was bound to be of insupportable weight to a myrmidon. Trianon was so much too pompous for the Fifteenth Louis that he had the Little Trianon built.

It was a house looking with its large eyes of windows over a park and woods, with the wing of the servant’s lodgings and stables on the left, where the windows were barred and the kitchens hidden by trellises of vines and creepers.

A path over a wooden bridge led to the Grand Trianon through a kitchen garden.

The King brought Prime Minister Choiseul into this garden to show him the improvements introduced to make the place fit for his grandson the Dauphin, and the Dauphiness.

Duke Choiseul admired everything and passed his comments with a courtier’s sagacity. He let the monarch say the place would become more pleasant daily and he added that it would be a family retreat for the sovereign.

“The Dauphiness is still a little uncouth, like all young German girls,” said Louis; “She speaks French nicely, but with an Austrian accent jarring on our ears. Here she will speak among friends and it will not matter.”

“She will perfect herself,” said the duke. “I have remarked that the lady is highly accomplished and accomplishes anything she undertakes.”

On the lawn they found the Dauphin taking the sun with a sextant. Louis Aguste, duke of Berry, was a meek-eyed, rosy complexioned man of seventeen, with a clumsy walk. He had a more prominent Bourbon nose than any before him, without its being a caricature. In his nimble fingers and able arms alone he showed the spirit of his race, so to express it.

“Louis,” said the King, loudly to be overheard by his grandson, “is a learned man, and he is wrong to rack his brain with science, for his wife will lose by it.”

“Oh, no,” corrected a feminine voice as the Dauphiness stepped out from the shrubbery, where she was chatting with a man loaded with plans, compass, pencil and notebook.

“Sire, this is my architect, Mique,” she said.

“Have you caught the family complaint of building?”

“I am going to turn this sprawling garden into a natural one!”

“Really? why, I thought that trees and grass and running water are natural enough.”

“Sire, you have to walk along straight paths between shaped boxwood trees, hewn at an angle of forty-five, to quote the Dauphin, and ponds agreeing with the paths, and star centres, and terraces! I am going to have arbors, rockeries, grottoes, cottages, hills, gorges, meadows—— ”

“For Dutch dolls to stand up in?” queried the King.

“Alas, Sire, for kings and princes like ourselves,” she replied, not seeing him color up, and that she had spoken a cutting truth.

“I hope you will not lodge your servants in your woods and on your rivers like Red Indians, in the natural life which Rousseau praises. If you do, only the Encyclopædists will eulogise you.”

“Sire, they would be too cold in huts, so I shall keep the out-buildings for them as they are.” She pointed to the windows of a corridor, over which were the servant’ sleeping rooms and under which were the kitchens.

“What do I see there?” asked the King, shielding his eyes with his hand, for he had short-sight.

“A woman, your Majesty,” said Choiseul.

“A young lady who is my reading-woman,” said the princess.

“It is Mdlle. de Taverney,” went on Choiseul.

“What, are you attaching the Taverneys to your house?”

“Only the girl.”

“Very good,” said the King, without taking his eyes off the barred window out of which innocently gazed Andrea, with no idea she was watched.

“How pale she is!” remarked the Prime Minister.

“She was nearly killed in the dreadful accident of the 30th of May, my lord.”

“For which we would have punished somebody severely,” said Louis, “but Chancellor Seguier proved it was the work of Fate. Only that fellow Bignon, Provost of the Merchants, was dismissed—and—poor girl! he deserved it.”

“Has she recovered?” asked Choiseul quickly.

“Yes, thank heaven!”

“She goes away,” said the King.

“She recognized your Majesty, and fled. She is timid.”

“A cheerless dwelling for a girl!”

“Oh, no, not so bad.”

“Let us have a look round inside, Choiseul?”

“Your Majesty, Council of Parliament at Versailles at half-past two.”

“Well, go and give those lawyers a shaking!”

And the sovereign, delighted to look at buildings, followed the Dauphiness who was delighted, also, to show her house. They passed Mdlle. de Taverney under the eaves of the little kitchen yard.

“This is my reader’s room,” remarked the Dauphiness. “I will show you it as a sample of how my ladies will fare.”

It was a suite of anteroom and two parlors. The furniture was placed; books, a harpsichord, and particularly a bunch of flowers in a Japanese Vase, attracted the King’s attention.

“What nice flowers! how can you talk of changing your garden? who the mischief supplies your ladies with such beauties? do they save any for the mistress?”

“Who is the gardener here so sweet upon Mdlle. de Taverney?”

“I do not know—Dr. Jussieu found me somebody.”

The King looked round with a curious eye, and elsewhere, before departing. The Dauphin was still taking the sun.

A LONG rank of carriages filled the Forest at Marly where the King was carrying on what was called an afternoon hunt. The Master of the Buckhounds had deer so selected that he could let the one out which would run before the hounds just as long as suited the sovereign.

On this occasion, his Majesty had stated that he would hunt till four P. M.

Countess Dubarry, who had her own game in view, promised herself that she would hunt the King as steadfastly as he would the deer.

But huntsmen propose and chance disposes. Chance upset the favorite’s project, and was almost as fickle as she was herself.

While talking politics with the Duke of Richelieu, who wanted by her help or otherwise to be First Minister instead of Choiseul, the countess—while chasing the King, who was chasing the roebuck—perceived all of a sudden, fifty paces off the road, in a shady grove, a broken down carriage. With its shattered wheels pointing to the sky, its horses were browsing on the moss and beech bark.

Countess Dubarry’s magnificent team, a royal gift, had out-stripped all the others and were first to reach the scene of the breakdown.

“Dear me, an accident,” said the lady, tranquilly.

“Just so, and pretty bad smash-up,” replied Richelieu, with the same coolness, for sensitiveness is unknown at court.

“Is that somebody killed on the grass?” she went on.

“It makes a bow, so I guess it lives.”

And at a venture Richelieu raised his own three-cocked hat.

“Hold! it strikes me it is the Cardinal Prince Louis de Rohan. What the deuce is he doing there?”

“Better go and see. Champagne, drive up to the upset carriage.”

The countess’s coachman quitted the road and drove to the grove. The cardinal was a handsome gentleman of thirty years of age, of gracious manners and elegant. He was waiting for help to come, with the utmost unconcern.