The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Shepheard's Calender, by Edmund Spenser

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Shepheard's Calender

Twelve Aeglogues Proportional to the Twelve Monethes

Author: Edmund Spenser

Illustrator: Walter Crane

Release Date: April 27, 2013 [EBook #42607]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SHEPHEARD'S CALENDER ***

Produced by Chris Curnow, Nicole Henn-Kneif and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

TWELVE AEGLOGUES PROPORTIONABLE TO THE TWELVE MONETHES

ENTITLED TO THE NOBLE AND VERTUOUS GENTLEMAN MOST WORTHY OF ALL TITLES BOTH OF LEARNING & CHIVALRY, MAISTER PHILIP SIDNEY.

BY EDMUND SPENSER:

NEWLY ADORNED

WITH TWELVE PICTURES AND OTHER DEVICES

BY

WALTER CRANE.

LONDON & NEW YORK

HARPER & BROTHERS

MDCCCXCVIII

TO THE MOST EXCELLENT AND LEARNED

BOTH ORATOR AND POET,

MAISTER GABRIEL HARVEY,

His very special and singular good friend E. K.

commendeth the good liking of this his good

labour, and the patronage of the new Poet.

Uncouth, unkiss'd, said the old famous poet Chaucer: whom for his excellency and wonderful skill in making, his scholar Lidgate, a worthy scholar of so excellent a maister, calleth the loadstar of our language: and whom our Colin Clout in his Ăglogue, calleth Tityrus the god of shepheards, comparing him to the worthiness of the Roman Tityrus, Virgil. Which proverb, mine own good friend M. Harvey, as in that good old poet it served well Pandar's purpose for the bolstering of his bawdy brocage, so very well taketh place in this our new Poet, who for that he is uncouth (as said Chaucer) is unkiss'd, and unknown to most men, is regarded but of a few. But I doubt not, so soon as his name shall come into the knowledge of men, and his worthiness be sounded in the trump of Fame, but that he shall be not only kiss'd, but also beloved of all, embraced of the most, and wonder'd at of the best. No less, I think, deserveth his wittiness in devising, his pithiness in uttering, his complaints of love so lovely, his discourses of pleasure so pleasantly, his pastoral rudeness, his moral wiseness, his due observing of decorum every where, in personages, in seasons, in matter, in speech; and generally, in all seemly simplicity of handling his matters, and framing his words: the which of many things which in him be strange, I know will seem the strangest, and words themselves being so ancient, the knitting of them so short and intricate, and the whole period and compass of speech so delightsome for the roundness, and so grave for the strangeness. And first of the words to speak, I grant they be something hard, and of most men unused, yet both English, and also used of most excellent authors, and most famous poets. In whom, when as this our Poet hath been much travailed and throughly read, how could it be, (as that worthy orator said) but that walking in the sun, although for other cause he walked, yet needs he must be sunburnt; and, having the sound of those ancient poets still ringing in his ears, he must needs, in singing, hit out some of their tunes. But whether he useth them by such casualty and custom, or of set purpose and choice, as thinking them fittest for such rustical rudeness of shepheards, either for that their rough sound would make his rhymes more ragged and rustical; or else because such old and obsolete words are most used of country folk, sure I think, and think I think not amiss, that they bring great grace, and, as one would say, authority to the verse. For albe, amongst many other faults, it specially be objected of Valla against Livy, and of other against Sallust, that with over much study they affect antiquity, as covering thereby credence and honour of elder years; yet I am of opinion, and eke the best learned are of the like, that those ancient solemn words are a great ornament, both in the one, and in the other: the one labouring to set forth in his work an eternal image of antiquity, and the other carefully discoursing matters of gravity and importance. For, if my memory fail not, Tully in that book, wherein he endeavoureth to set forth the pattern of a perfect orator, saith that ofttimes an ancient word maketh the style seem grave, and as it were reverend, no otherwise than we honour and reverence gray hairs for a certain religious regard, which we have of old age. Yet neither every where must old words be stuffed in, nor the common dialect and manner of speaking so corrupted thereby, that, as in old buildings, it seem disorderly and ruinous. But all as in most exquisite pictures they us?e to blaze and pourtray not only the dainty lineaments of beauty, but also round about it to shadow the rude thickets and craggy clifts, that, by the baseness of such parts, more excellency may accrue to the principal: for oftentimes we find ourselves, I know not how, singularly delighted with the shew of such natural rudeness, and take great pleasure in that disorderly order. Even so do those rough and harsh terms enlumine, and make more clearly to appear, the brightness of brave and glorious words. So oftentimes a discord in music maketh a comely concordance: so great delight took the worthy poet Alceus to behold a blemish in the joint of a well-shaped body. But, if any will rashly blame such his purpose in choice of old and unwonted words, him may I more justly blame and condemn, or of witless headiness in judging, or of heedless hardiness in condemning: for, not marking the compass of his bent, he will judge of the length of his cast: for in my opinion it is one especial praise of many, which are due to this Poet, that he hath laboured to restore, as to their rightful heritage, such good and natural English words, as have been long time out of use, and almost clean disherited. Which is the only cause, that our mother tongue, which truly of itself is both full enough for prose, and stately enough for verse, hath long time been counted most bare and barren of both. Which default when as some endeavoured to salve and recure, they patched up the holes with pieces and rags of other languages, borrowing here of the French, there of the Italian, every where of the Latin; not weighing how ill those tongues accord with themselves, but much worse with ours: So now they have made our English tongue a gallimaufrey, or hodgepodge of all other speeches. Other some not so well seen in the English tongue, as perhaps in other languages, if they happen to hear an old word, albeit very natural and significant, cry out straightway, that we speak no English, but gibberish, or rather such as in old time Evander's mother spake: whose first shame is, that they are not ashamed, in their own mother tongue, to be counted strangers and aliens. The second shame no less than the first, that what so they understand not, they straightway deem to be senseless, and not at all to be understood. Much like to the mole in Ăsop's fable, that, being blind herself, would in no wise be persuaded that any beast could see. The last, more shameful than both, that of their own country and natural speech, which together with their nurse's milk they sucked, they have so base regard and bastard judgment, that they will not only themselves not labour to garnish and beautify it, but also repine, that of other it should be embellished. Like to the dog in the manger, that himself can eat no hay, and yet barketh at the hungry bullock, that so fain would feed: whose currish kind, though it cannot be kept from barking, yet I conne them thank that they refrain from biting.

Now, for the knitting of sentences, which they call the joints and members thereof, and for all the compass of the speech, it is round without roughness, and learned without hardness, such indeed as may be perceived of the least, understood of the most, but judged only of the learned. For what in most English writers useth to be loose, and as it were unright, in this Author is well grounded, finely framed, and strongly trussed up together. In regard whereof, I scorn and spue out the rakehelly rout of our ragged rhymers (for so themselves use to hunt the letter) which without learning boast, without judgment jangle, without reason rage and foam, as if some instinct of poetical spirit had newly ravished them above the meanness of common capacity. And being, in the midst of all their bravery, suddenly, either for want of matter, or rhyme; or having forgotten their former conceit; they seem to be so pained and travailed in their remembrance, as it were a woman in childbirth, or as that same Pythia, when the trance came upon her. "Os rabidum fera corda domans," etc.

Nathless, let them a God's name feed on their own folly, so they seek not to darken the beams of others' glory. As for Colin, under whose person the Author's self is shadowed, how far he is from such vaunted titles and glorious shews, both himself sheweth, where he saith:

And,

And also appeareth by the baseness of the name, wherein it seemeth he chose rather to unfold great matter of argument covertly than, professing it, not suffice thereto accordingly. Which moved him rather in Ăglogues than otherwise to write, doubting perhaps his ability, which he little needed, or minding to furnish our tongue with this kind, wherein it faulteth; or following the example of the best and most ancient poets, which devised this kind of writing, being both so base for the matter, and homely for the manner, at the first to try their abilities; and as young birds, that be newly crept out of the nest, by little first prove their tender wings, before they make a greater flight. So flew Theocritus, as you may perceive he was already full fledged. So flew Virgil, as not yet well feeling his wings. So flew Mantuane, as not being full somm'd. So Petrarch. So Boccace. So Marot, Sanazarius, and also divers other excellent both Italian and French poets, whose footing this author every where followeth: yet so as few, but they be well scented, can trace him out. So finally flieth this our new Poet as a bird whose principals be scarce grown out, but yet as one that in time shall be able to keep wing with the best. Now, as touching the general drift and purpose of his Ăglogues, I mind not to say much, himself labouring to conceal it. Only this appeareth, that his unstayed youth had long wander'd in the common labyrinth of love, in which time to mitigate and allay the heat of his passion, or else to warn (as he saith) the young shepheards, his equals and companions, of his unfortunate folly, he compiled these twelve Ăglogues, which, for that they be proportioned to the state of the twelve monethes, he termeth it the Shepheard's Calender, applying an old name to a new work. Hereunto have I added a certain gloss, or scholion, for the exposition of old words and harder phrases; which manner of glossing and commenting, well I wot, will seem strange and rare in our tongue: yet, for so much as I knew many excellent and proper devices, both in words and matter, would pass in the speedy course of reading either as unknown, or as not marked; and that in this kind, as in other, we might be equal to the learned of other nations; I thought good to take the pains upon me, the rather for that by means of some familiar acquaintance I was made privy to his counsel and secret meaning in them, as also in sundry other works of his. Which albeit I know he nothing so much hateth, as to promulgate, yet thus much have I adventured upon his friendship, himself being for long time far estranged; hoping that this will the rather occasion him to put forth divers other excellent works of his, which sleep in silence; as his Dreams, his Legends, his Court of Cupid, and sundry others, whose commendation to set out were very vain, the things though worthy of many, yet being known to few. These my present pains, if to any they be pleasurable or profitable, be you judge, mine own Maister Harvey, to whom I have both in respect of your worthiness generally, and otherwise upon some particular and special considerations, vowed this my labour, and the maidenhead of this our common friend's poetry; himself having already in the beginning dedicated it to the noble and worthy gentleman, the right worshipful Maister Philip Sidney, a special favourer and maintainer of all kind of learning. Whose cause, I pray you, sir, if envy shall stir up any wrongful accusation, defend with your mighty rhetoric and other your rathe gifts of learning, as you can, and shield with your good will, as you ought, against the malice and outrage of so many enemies, as I know will be set on fire with the sparks of his kindled glory. And thus recommending the Author unto you, as unto his most special good friend, and myself unto you both, as one making singular account of two so very good and so choice friends, I bid you both most heartily farewell, and commit you and your commendable studies to the tuition of the Greatest.

Your own assuredly to be commanded,

E. K. 1

P.S.—Now I trust, M. Harvey, that upon sight of your special friend's and fellow poet's doings, or else for envy of so many unworthy Quidams, which catch at the garland which to you alone is due, you will be persuaded to pluck out of the hateful darkness those so many excellent English poems of yours which lie hid, and bring them forth to eternal light. Trust me, you do both them great wrong, in depriving them of the desired sun; and also yourself, in smothering your deserved praises; and all men generally, in withholding from them so divine pleasures, which they might conceive of your gallant English verses, as they have already done of your Latin poems, which, in my opinion, both for invention and elocution are very delicate and super-excellent. And thus again I take my leave of my good M. Harvey. From my lodging at London this tenth of April 1579.

THE GENERAL ARGUMENT OF THE WHOLE BOOK.

Little, I hope, needeth me at large to discourse the first original of Æglogues, having already touched the same. But, for the word Æglogues I know is unknown to most, and also mistaken of some of the best learned, (as they think,) I will say somewhat thereof, being not at all impertinent to my present purpose.

They were first of the Greeks, the inventors of them, called Aeglogai, as it were Aegon, or Aeginomon logi, that is, Goatherds' tales. For although in Virgil and others the speakers be more shepheards than goatherds, yet Theocritus, in whom is more ground of authority than in Virgil, this specially from that deriving, as from the first head and wellspring, the whole invention of these Æglogues maketh goatherds the persons and authors of his tales. This being, who seeth not the grossness of such as by colour of learning would make us believe, that they are more rightly termed Eclogai, as they would say, extraordinary discourses of unnecessary matter: which definition albe in substance and meaning it agree with the nature of the thing, yet no whit answereth with the analysis and interpretation of the word. For they be not termed Eclogues, but Æglogues; which sentence this Author very well observing, upon good judgment, though indeed few goatherds have to do herein, nevertheless doubteth not to call them by the used and best known name. Other curious discourses hereof I reserve to greater occasion.

These twelve Æglogues, every where answering to the seasons of the twelve monethes, may be well divided into three forms or ranks. For either they be plaintive, as the first, the sixth, the eleventh, and the twelfth; or recreative, such as all those be, which contain matter of love, or commendation of special personages; or moral, which for the most part be mixed with some satyrical bitterness; namely, the second, of reverence due to old age; the fifth, of coloured deceit; the seventh and ninth, of dissolute shepheards and pastors; the tenth, of contempt of Poetry and pleasant Wits. And to this division may every thing herein be reasonably applied; a few only except, whose special purpose and meaning I am not privy to. And thus much generally of these twelve Æglogues. Now will we speak particularly of all, and first of the first, which he calleth by the first moneth's name, Januarie: wherein to some he may seem foully to have faulted, in that he erroneously beginneth with that moneth, which beginneth not the year. For it is well known, and stoutly maintained with strong reasons of the learned, that the year beginneth in March; for then the sun reneweth his finished course, and the seasonable spring refresheth the earth, and the pleasance thereof, being buried in the sadness of the dead winter now worn away, reliveth.

This opinion maintain the old Astrologers and Philosophers, namely, the reverend Andalo, and Macrobius in his Holy Days of Saturn; which account also was generally observed both of Grecians and Romans. But, saving the leave of such learned heads, we maintain a custom of counting the seasons from the moneth Januarie, upon a more special cause than the heathen Philosophers ever could conceive, that is, for the Incarnation of our mighty Saviour, and Eternal Redeemer the Lord Christ, who as then renewing the state of the decayed world, and returning the compass of expired years to their former date and first commencement, left to us his heirs a memorial of his birth in the end of the last year and beginning of the next. Which reckoning, beside that eternal monument of our salvation, leaneth also upon good proof of special judgment.

For albeit that in elder times, when as yet the count of the year was not perfected, as afterward it was by Julius Cæsar, they began to tell the monethes from March's beginning, and according to the same, God (as is said in Scripture) commanded the people of the Jews, to count the moneth Abib, that which we call March, for the first moneth, in remembrance that in that moneth he brought them out of the land of Egypt: yet, according to tradition of latter times it hath been otherwise observed, both in government of the Church and rule of mightiest realms. For from Julius Cæsar who first observed the leap year, which he called Bissextilem Annum, and brought into a more certain course the odd wand'ring days which of the Greeks were called Hyperbainontes, of the Romans Intercalares, (for in such matter of learning I am forced to use the terms of the learned,) the monethes have been numbered twelve, which in the first ordinance of Romulus were but ten, counting but 304 days in every year, and beginning with March. But Numa Pompilius, who was the father of all the Roman ceremonies and religion, seeing that reckoning to agree neither with the course of the sun nor the moon, thereunto added two monethes, Januarie and Februarie; wherein it seemeth, that wise king minded upon good reason to begin the year at Januarie, of him therefore so called tanquam janua anni, the gate and entrance of the year; or of the name of the god Janus, to which god for that the old Paynims attributed the birth and beginning of all creatures new coming into the world, it seemeth that he therefore to him assigned the beginning and first entrance of the year. Which account for the most part hath hitherto continued: notwithstanding that the Egyptians begin their year at September; for that, according to the opinion of the best Rabbins and very purpose of the Scripture itself, God made the world in that moneth, that is called of them Tisri. And therefore he commanded them to keep the feast of Pavilions in the end of the year, in the xv. day of the seventh moneth, which before that time was the first.

But our author, respecting neither the subtilty of the one part, nor the antiquity of the other, thinketh it fittest, according to the simplicity of common understanding, to begin with Januarie; weening it perhaps no decorum that shepheards should be seen in matter of so deep insight, or canvass a case of so doubtful judgment. So therefore beginneth he, and so continueth he throughout.

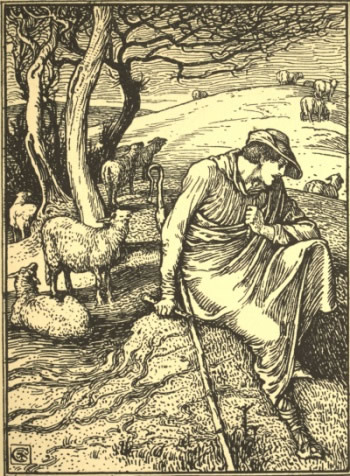

JANUARIE. ÆGLOGA PRIMA. ARGUMENT.

In this first Æglogue Colin Clout, a shepheard's boy, complaineth himself of his unfortunate love, being but newly (as seemeth) enamoured of a country lass called Rosalind: with which strong affection being very sore travailed, he compareth his careful case to the sad season of the year, to the frosty ground, to the frozen trees, and to his own winter-beaten flock. And lastly, finding himself robbed of all former pleasance and delight, he breaketh his pipe in pieces, and casteth himself to the ground.

COLIN CLOUT.

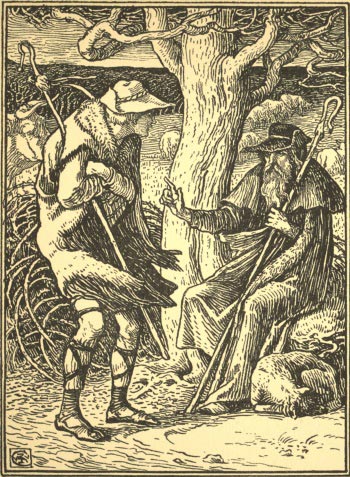

FEBRUARIE. ÆGLOGA SECUNDA. ARGUMENT.

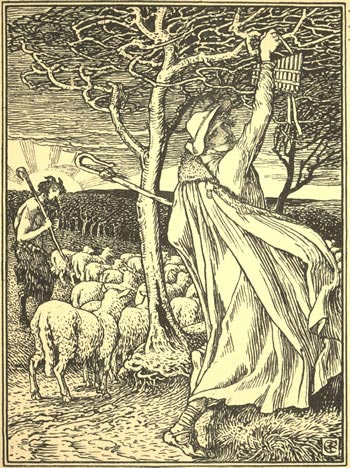

This Æglogue is rather moral and general than bent to any secret or particular purpose. It specially containeth a discourse of old age, in the person of Thenot, an old shepheard, who, for his crookedness and unlustiness, is scorned of Cuddie, an unhappy herdman's boy. The matter very well accordeth with the season of the moneth, the year now drooping, and as it were drawing to his last age. For as in this time of year, so then in our bodies, there is a dry and withering cold, which congealeth the curdled blood, and freezeth the weather-beaten flesh, with storms of Fortune and hoar-frosts of Care. To which purpose the old man telleth a tale of the Oak and the Brier, so lively, and so feelingly, as, if the thing were set forth in some picture before our eyes, more plainly could not appear.

CUDDIE. THENOT.

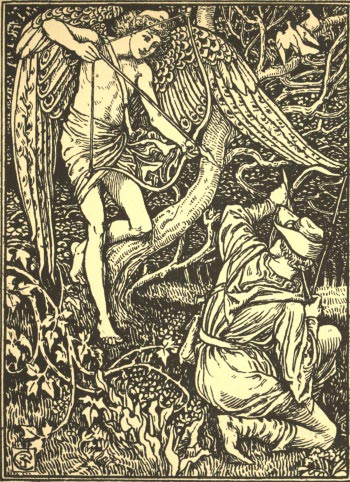

In this Æglogue two Shepheards' Boys, taking occasion of the season, begin to make purpose of love, and other pleasance which to springtime is most agreeable. The special meaning hereof is, to give certain marks and tokens, to know Cupid the poets' god of Love. But more particularly, I think, in the person of Thomalin, is meant some secret friend, who scorned Love and his knights so long, till at length himself was entangled, and unwares wounded with the dart of some beautiful regard, which is Cupid's arrow.

WILLY. THOMALIN.

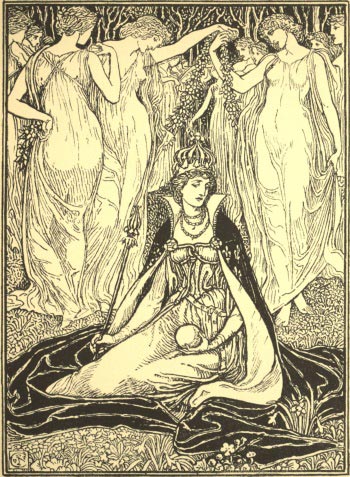

This Æglogue is purposely intended to the honour and praise of our most gracious sovereign, Queen Elizabeth. The speakers hereof be Hobbinol and Thenot, two shepheards: the which Hobbinol, being beforementioned greatly to have loved Colin, is here set forth more largely, complaining him of that boy's great misadventure in love; whereby his mind was alienated and withdrawn not only from him, who most loved him, but also from all former delights and studies, as well in pleasant piping, as cunning rhyming and singing, and other his laudable exercises. Whereby he taketh occasion, for proof of his more excellency and skill in poetry, to record a song, which the said Colin sometime made in honour of her Majesty, whom abruptly he termeth Elisa.

THENOT. HOBBINOL.

In this fifth Ăglogue, under the person of two shepheards, Piers and Palinode, be represented two forms of Pastors or Ministers, or the Protestant and the Catholic; whose chief talk standeth in reasoning, whether the life of the one must be like the other; with whom having shewed, that it is dangerous to maintain any fellowship, or give too much credit to their colourable and feigned good-will, he telleth him a tale of the Fox, that, by such a counterpoint of craftiness, deceived and devoured the credulous Kid.

PALINODE. PIERS.

This Ăglogue is wholly vowed to the complaining of Colin's ill success in his love. For being (as is aforesaid) enamoured of a country lass Rosalind, and having (as seemeth) found place in her heart, he lamenteth to his dear friend Hobbinol, that he is now forsaken unfaithfully, and in his stead Menalcas, another shepheard, received disloyally. And this is the whole Argument of this Ăglogue.

HOBBINOL. COLIN CLOUT.

This Ăglogue is made in the honour and commendation of good shepheards, and to the shame and dispraise of proud and ambitious pastors: such as Morrell is here imagined to be.

THOMALIN. MORRELL. 11

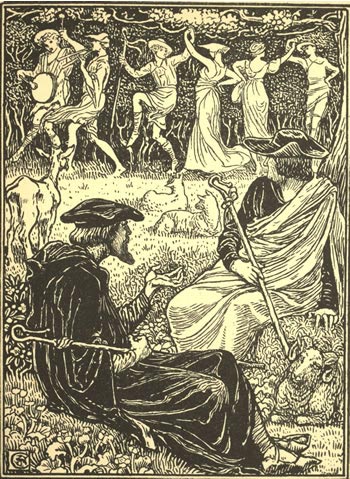

In this Ăglogue is set forth a delectable controversy, made in imitation of that in Theocritus: whereto also Virgil fashioned his third and seventh Ăglogue. They chose for umpire of their strife, Cuddy, a neat-herd's boy; who, having ended their cause, reciteth also himself a proper song, whereof Colin he saith was author.

WILLIE. PERIGOT. CUDDIE.

Herein Diggon Davie is devised to be a shepheard that, in hope of more gain, drove his sheep into a far country. The abuses whereof, and loose living of Popish prelates, by occasion of Hobbinol's demand, he discourseth at large.

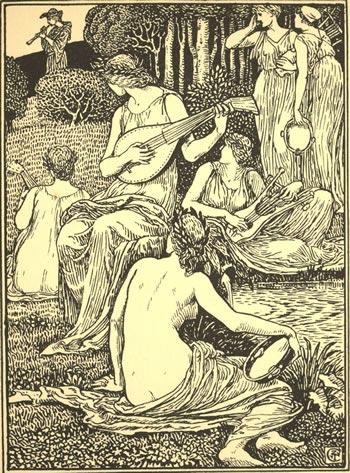

In Cuddie is set out the perfect pattern of a Poet, which, finding no maintenance of his state and studies, complaineth of the contempt of Poetry, and the causes thereof: specially having been in all ages, and even amongst the most barbarous, always of singular account and honour, and being indeed so worthy and commendable an art; or rather no art, but a divine gift and heavenly instinct not to be gotten by labour and learning, but adorned with both; and poured into the wit by a certain Enthousiasmos and celestial inspiration, as the Author hereof elsewhere at large discourseth in his book called The English Poet, which book being lately come to my hands, I mind also by God's grace, upon further advisement, to publish.

PIERS. CUDDIE.

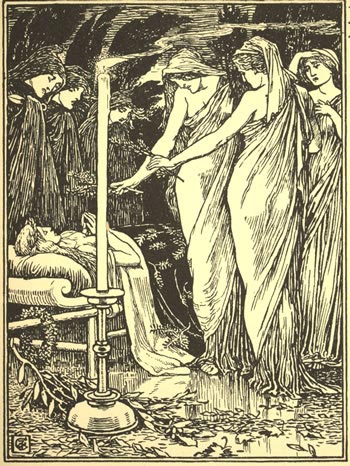

In this xi. Ăglogue he bewaileth the death of some maiden of great blood, whom he calleth Dido. The personage is secret, and to me altogether unknown, albeit of himself I often required the same. This Ăglogue is made in imitation of Marot his song, which he made upon the death of Loyes the French Queen; but far passing his reach, and in mine opinion all other the Ăglogues of this Book.

THENOT. COLIN.

This Ăglogue (even as the first began) is ended with a complaint of Colin to god Pan; wherein, as weary of his former ways, he proportioned his life to the four seasons of the year; comparing his youth to the spring time, when he was fresh and free from love's folly. His manhood to the summer, which, he saith, was consumed with great heat and excessive drouth, caused through a comet or blazing star, by which he meaneth love; which passion is commonly compared to such flames and immoderate heat. His ripest years he resembleth to an unseasonable harvest, wherein the fruits fall ere they be ripe. His latter age to winter's chill and frosty season, now drawing near to his last end.

NOTES

Page xviii, note 1.—The name of the writer of this letter is unknown.

Page 5, note 2.—"Hobbinol:" the author's friend Gabriel Harvey.

Page 10, note 3.—"Good Friday:" Good Friday is said to frown, as being a fast-day.

Page 16, note 4.—Thenot's emblem means, in substance, that God, who is aged Himself, being without beginning of days, makes those whom He loves, to be aged, like Himself; and that it is a mark of His favour to be old. Cuddie's emblem is, "No old man fears God"—a sarcasm against Thenot.

Page 29, note 5.—"Tawdry:" is here used in its primitive sense, denoting something bought at the fair of St. Ethelred, or St. Awdrey.

Page 30, note 6.—"This poesy is taken out of Virgil, and there of him used in the person of Ăneas to his mother Venus, appearing to him in likeness of one of Diana's damsels; being there most divinely set forth. To which similitude of divinity Hobbinol comparing the excellency of Elisa, and being through the worthiness of Colin's song, as it were, overcome with the hugeness of his imagination, bursteth out in great admiration, (O quam te memorem virgo!) being otherwise unable, than by sudden silence, to express the worthiness of his conceit. Whom Thenot answereth with another part of the like verse, as confirming by his grant and approvance, that Elisa is no whit inferior to the majesty of her, of whom the poet so boldly pronounced, O dea certe!"—E. K.

Page 35, note 7.—"Algrind:" Archbishop Grindall.

Page 37, note 8.—"Fox," "Kid:" "By the Kid may be understood the simple sort of the faithful and true Christians; by his dam, Christ, that hath already with careful watchwords (as here doth the Goat) warned her little ones to beware of such doubling deceit; by the Fox, the false and faithless Papists, to whom is no credit to be given, nor fellowship to be used."—E. K.

Page 41, note 9.—"Sir John:" a name applied to a Popish priest.

Page 47, note 10.—"Tityrus:" Chaucer is meant.

Page 53, note 11.—"Morrell:" supposed to be Elmer, or Aylmer, Bishop of London.

Page 53, note 12.—"The sun:" the sun enters Leo in July.

Page 59, note 13.—"An eagle:" the same story is told of the death of Eschylus.

Pages 68, 69, note 14.—"The meaning hereof is very ambiguous: for Perigot by his posy claiming the conquest, and Willie not yielding, Cuddie the arbiter of their cause, and patron of his own, seemeth to challenge it, as his due, saying, that he is happy which can; so abruptly ending; but he meaneth either him, that can win the best, or moderate himself being best, and leave off with the best."—E. K.

Page 77, note 15.—"Saxon king:" King Edgar, in whose reign wolves are said to have disappeared in England.

Page 84, note 16.—"Elisa:" Queen Elizabeth; the "Worthy" is the Earl of Leicester.

Page 87, note 17.—This emblem is portion of a Latin verse, expressing the thought of the pastoral, that poetry is a fervid glow of inspiration which animates and kindles.

Page 91, note 18.—"Fishes:" the sun enters the constellation Pisces in November.

Page 92, note 19.—"Dido" and "great shepheard" both refer to real persons unknown.

Page 94, note 20.—"Wrought with a chief:" wrought into a head, like a nosegay.

Page 101, note 21.—Translated freely from the French of Marot.

Page 107, note 22.—"The pilgrim:" perhaps the author of the "Visions of Pierce Ploughman."

Accloyeth, encumbereth.

Accoyed, daunted.

Adawed, daunted.

Adays, every day.

Albe, although.

Alegge, assuage.

Algate, at all events.

All, although.

All be it, although it be.

All-to, entirely.

All-to rathe, too early.

Als, also.

Arede, declare, repeat, explain.

Assayed, affected.

Assert, befall.

Assot, stupid.

As weren overwent, as if we were overcome.

At erst, at last.

Attone, also.

Attones, at same time.

Availe, bring down, lower.

Availes, is lowered.

Babes, dolls.

Bale, ruin.

Balk, miss.

Bate, bated, fed.

Bedight, affected.

Behight, behote, called.

Belive, promptly.

Bellibone (belle et bonne), good and beautiful one.

Bend, band.

Bene, are.

Benempt, named, mentioned.

Bent, obedient.

Besprint, besprent, besprinkled.

Betight, betide, happened.

Bett, better.

Bidding base, game of prison base.

Biggen, cap.

Bin, be.

Black bower, i.e., hell.

Bloncket liveries, gray coats.

Blont, unpolished.

Borrell, rustic.

Borrow, pledge, surety, Saviour.

Brace, compass.

Brag, bragly, proudly.

Breme, sharp.

Brent, burnt.

Brere, brier.

Brocage, pimping.

Bugle, beads.

But, unless.

Buxom, yielding.

Can, knows.

Careful, sorrowful.

Careful case, unhappy condition.

Cark, sorrow.

Chaffred, sold or exchanged.

Chamfred, wrinkled.

Charm, temper, tune.

Chevisance, performance, result, bargain.

Chips, fragments.

Collusion, cunning.

Con, know.

Cond, learned.

Confusion, destruction.

Contempt, contemned.

Convenable, conformable.

Corb, crooked.

Cosset, lamb.

Cote, sheepfold.

Courage, mind.

Couth, knew how, could.

Cracknels, biscuits.

Crag, neck.

Crank, courageous.

Crumenall, purse.

Dapper ditties, pretty songs.

Deed, doing, composing.

Defast, defaced.

Dempt, deemed.

Depeincten, painted.

Derring, manly deeds.

Derring-do, daring deeds.

Devoir, duty.

Dight, adorn, prepare; adorned, prepared, dealt with.

Dint, pang of grief.

Dirk, darkly.

Dirks, darkens.

Disease, disturb.

Dole, dool, sorrow, grief.

Doom, judgment.

Doubted, redoubted.

Drent, drowned, perished.

Eath, easy.

Eft, quickly, soon.

Eftsoons, immediately.

Eked, increased.

Eld, age.

Embrave, adorn.

Emprise, enterprise.

Enaunter, lest, lest that.

Enchased, engraved.

Encheason, occasion.

Entrailed, intwined.

Erst, before, at once.

Expert, experience.

Faitours, villains, vagabonds.

Falsers, deceivers.

Fay, faith.

File, defile.

Fined, sifted.

Fon, fool.

Fond, foolish.

Fondness, folly.

Fonly, foolishly.

Foresaid, banished.

Foreslow, impede, obstruct.

Forestall, prevent.

Forhaile, distress.

For-say, forsake.

Forswat, spent with heat.

Forswonk, overlaboured.

Forthy, therefore, on that account.

Frenne, stranger.

Frorne, frozen.

Frowy, musty.

Galage, wooden shoe.

Gang, go.

Gars, makes.

Gastful, dreary.

Gate, way.

Gelt, a gilded girdle.

Giant, Atlas.

Giusts, tournaments.

Go, gone.

Gree, degree.

Greet, weep; mourning.

Gride, gryde, pierced.

Gross, whole.

Harbrough, habitation.

Hask, basket.

Haveour, demeanour.

Heme, home.

Hent, took, taken.

Hentst, takest.

Herdgrooms, herdsmen.

Herie, hery, honour, praise.

Herse, rehearsal, tale.

Heydeguys, dances.

Hidder and shidder, him and her.

Hight, purports; was named.

Hote, mentioned; was called.

If, unless.

Ilk, the same.

Inly, inwardly.

Inn, abode.

Jovisance, joyousness.

Keep, care, charge.

Ken, know.

Kend, known.

Kenst, knowest.

Kerns, farmers.

Kirk, church.

Knack, trick.

Knaves, servants.

Kydst, knowest.

Laid, faint.

Larded, fattened.

Latched, caught.

Lays, leas, fields.

Leasing, falsehood, lies.

Lere, lore, lesson; learn.

Lever, rather.

Levin, lightning.

Lewd, foolish.

Lewdly, foolishly.

Lief, dear, beloved.

Lig, ligg, liggen, lie.

Loord, fellow.

Lope, leaped.

Lorn, left, lost.

Lorrell, ignorant, worthless fellow.

Louted, did honour.

Lust, wishest.

Lustihed, pleasure.

Lustless, languid.

Maintenance, behaviour.

Make, versify.

Maugre, in spite of.

May, maid.

May-buskets, May-bushes.

Mazer, bowl.

Medle, mingle.

Meint, mingled.

Melling, meddling.

Men of the lay, laymen.

Ment, mingled.

Merciable, merciful.

Mickle, much.

Miller's round, a dance.

Mirk, very obscure.

Miscreance, unbelief.

Misgone, gone astray.

Missay, say evil.

Mister men, kind of men.

Mister saying, kind of speech.

Miswent, gone astray.

Mizzle, to rain a little.

Mochell, much.

Moe, more.

Most what, affairs.

Most-what, for the most part.

Musical, music.

Narre, nearer.

N'as, has not.

Newell, novelty.

Nighly, nearly so much.

Nill, will not.

N'is, is not.

N'ote, know not.

Nought seemeth, is unseemly.

Nould, would not.

Overcrawed, overcrowed.

Overgone, surpassed.

Overhale, draw over.

Overture, open place.

Paddocks, toads.

Pained, exerted himself.

Paramours, lovers.

Paunce, pansy.

Perdie, in truth, truly.

Peregall, equal.

Perk, pert.

Pert, open.

Pieced, imperfect.

Pight, put, placed.

Plainful, lamentable.

Prick, mark.

Pricket, buck.

Prief, proof.

Prime, spring.

Primrose, chief flower.

Pumie, pumice.

Purchase, obtain.

Purpose, conversation.

Quaint, strange.

Quell, abate.

Queme, please.

Quick, alive.

Quit, deliver.

Rathe, early.

Rather, born early.

Record, repeat.

Rede, saying; advise, tell.

Reliven, live again.

Ribaudry, ribaldry.

Rife, frequent.

Rifely, abundantly.

Rine, rind.

Romish Tityrus, Virgil.

Ronts, young bullocks.

Roundel, roundelay.

Routs, companies.

Roved, shot.

Sale, wicker net.

Sam, together.

Sample, example.

Saye, silk.

Scope, mark aimed at.

Seely, simple.

Sheen, bright.

Shend, disgrace.

Shepheard, Abel, p. 56; Endymion,

p. 55; Orpheus, p. 84;

Paris, p. 57.

Shield, forbid.

Sib, related.

Sich, such.

Sicker, siker, surely, truly.

Sike, such.

Site, situation.

Sithence, sithens, since, since

that time.

Siths, times.

Sits, becomes.

Sits not, is not becoming.

Skill in making, in writing poetry.

Slipper, slippery, uncertain.

Smirk, nice.

Snebbe, revile.

Somdele, somewhat, in some degree.

Some quick, something alive.

Sommed, feathered.

Soote, sweetly.

Sooth, soothsaying.

Sops-in-wine, a flower.

Sovenance, remembrance.

So well the wed, of such sound morals.

Sperr, shut.

Spill, spoil, ruin, injure.

Stank, weary.

State, stoutly.

Steven, noise.

Stound, effort; hour.

Stounds, pains; occasions.

Stour, assault.

Stoure, occasion.

Stoures, attacks.

Stowre, affliction, violence.

Strain, imbody in strains.

Strait, strict.

Strow, display.

Stud, trunk.

Sullen, sad.

Surquedry, pride.

Swink, toil.

Tabrere, taborer.

Teen, sorrow.

That, that which.

Thereto, also.

Thick, thicket.

Thilk, this, these, this same, that

same.

Tickle, uncertain.

Tinct, coloured.

Tityrus, Chaucer.

Tod, thick bush.

To-force, perforce.

Tooting, looking about.

Totty, wavering.

Trace, go.

Trains, snares.

Trode, troad, tread, path.

Truss, bundle.

Tway, two.

Uncouth, unknown.

Underfong, tamper with, undertake.

Undersay, say in contradiction.

Uneath, scarcely.

Unkempt, unpolished.

Unkent, unknown.

Unlustiness, feebleness.

Unnethes, scarcely.

Unsoot, unsweet.

Uprist, uprisen.

Utter, put forth.

Venteth, snuffeth.

Vetchy, of pease straw.

Virelays, songs.

War, worse.

Warre, ware.

Weanel wast, weaned youngling.

Weed, dress.

Weet, know.

Weighed, esteemed.

Weld, wield, bear.

Welked, decreased, shortened.

Well apaid, in good condition.

Wellaway, alas!

Wend, go.

What, matter, thing.

What is he for a lad? what sort of lad is he?

Whilome, formerly.

Widder, wider.

Wight, active.

Wightly, quickly.

Wimble, nimble.

Wisards, learned men.

Wist, knew.

Witen, blame.

Wonned, dwelt.

Wood, mad, wild.

Worthy wite, deserved blame.

Wot, wote, know.

Wot ne, know not.

Woundless, unwounded.

Wrack, violence.

Wroken, avenged.

Yblent, blinded.

Yconned, conned.

Yede, go, went.

Yeven, given.

Yfere, together.

Ygo, ygoe, gone.

Yode, went.

Yond, yonder.

Ypent, pent, confined.

Yshend, disparage.

Ytake, taken, overcome.

Ytost, be harassed.

Ywis, truly.

Transcriber's Notes:

Variations in spelling, punctuation and hyphenation have been retained except in obvious cases of typographical error:

"puo" has been changed to "pu˛"

"anchora" has been changed to "ancora"

"AEGLOGA" has been changed to "ĂGLOGA"

Emblem images have been moved to end of chapters.

End of Project Gutenberg's The Shepheard's Calender, by Edmund Spenser

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SHEPHEARD'S CALENDER ***

***** This file should be named 42607-h.htm or 42607-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/4/2/6/0/42607/

Produced by Chris Curnow, Nicole Henn-Kneif and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need, are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at http://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

http://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at http://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit http://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations.

To donate, please visit: http://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart is the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

http://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.