Project Gutenberg's A History of Wood-Engraving, by George Edward Woodberry This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: A History of Wood-Engraving Author: George Edward Woodberry Release Date: September 1, 2012 [EBook #40638] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A HISTORY OF WOOD-ENGRAVING *** Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1882, by

H A R P E R & B R O T H E R S,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

All rights reserved.

IN this book I have attempted to gather and arrange such facts as should be known to men of cultivation interested in the art of engraving in wood. I have, therefore, disregarded such matter as seems to belong rather to descriptive bibliography, and have treated wood-engraving, in its principal works, as a reflection of the life of men and an illustration of successive phases of civilization. Where there is much disputed ground, particularly in the early history of the art, the writers on whom I have relied are referred to, and those who adopt a different view are named; but where the facts seemed plain, and are easily verifiable, reference did not appear necessary.

In conclusion, I have the honor to acknowledge my obligations to the officers of the Boston Public Library, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and the Harvard College Library, for permission to reproduce several cuts in their possession; and to Mr. Lindsay Swift, of the Boston Public Library, for the list of authorities at the end of the volume. Especially it is my pleasant duty to thank Professor Charles Eliot Norton, of Harvard University, from whose curious and valuable collection more than half of these illustrations are derived, both for them and for suggestion, advice, and criticism, without which, indeed, the work could not have been written.

GEORGE EDWARD WOODBERRY.

| I | |

| PAGE | |

| THE ORIGIN OF THE ART | 13 |

| II | |

| THE BLOCK-BOOKS | 30 |

| III | |

| EARLY PRINTED BOOKS IN THE NORTH | 45 |

| IV | |

| EARLY ITALIAN WOOD-ENGRAVING | 65 |

| V | |

| ALBERT DÜRER AND HIS SUCCESSORS | 90 |

| VI | |

| HANS HOLBEIN | 116 |

| VII | |

| THE DECLINE AND EXTINCTION OF THE ART | 135 |

| VIII | |

| MODERN WOOD-ENGRAVING | 151 |

| A LIST OF THE PRINCIPAL WORKS UPON WOOD-ENGRAVING USEFUL TO STUDENTS | 211 |

| INDEX | 217 |

[Some of the illustrations have been moved from inside of paragraphs for ease of reading. Clicking on the figure number in this list will take you to it. Click directly on the image to view it in a larger size. (n. etext transcriber)]

| FIG. | PAGE | |

| 1. | —From “Epistole di San Hieronymo Volgare.” Ferrara, 1497. (Initial letter) | 13 |

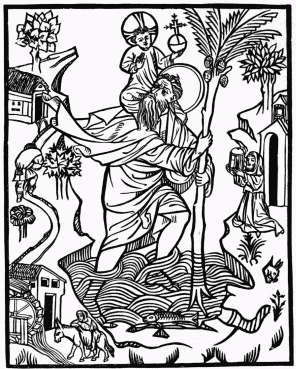

| 2. | —St. Christopher, 1423. From Ottley’s “Inquiry into the Origin and Early History of Engraving upon Copper and in Wood” | 22 |

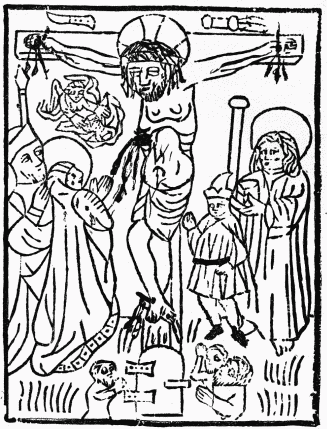

| 3. | —The Crucifixion. From the Manuscript “Book of Devotion.” 1445 | 24 |

| 4. | —From the “Epistole di San Hieronymo.” 1497. (Initial letter) | 30 |

| 5. | —Elijah Raiseth the Widow’s Son (1 K. xvii.). The Raising of Lazarus (Jno. xi.). Elisha Raiseth the Widow’s Son (2 K. iv.). From the original in the possession of Professor Norton, of Cambridge | 34 |

| 6. | —The Creation of Eve. From the fac-simile of Berjeau | 35 |

| 7. | —Initial letter. Source unknown | 45 |

| 8. | —The Grief of Hannah. From the Cologne Bible, 1470-’75 | 49 |

| 9. | —Illustration of Exodus I. From the Cologne Bible, 1470-’75 | 51 |

| 10. | —The Fifth Day of Creation. From Schedel’s “Liber Chronicarum.” Nuremberg, 1493 | 54 |

| 11. | —The Dancing Deaths. From Schedel’s “Liber Chronicarum.” Nuremberg, 1493 | 56 |

| 12. | —Jews Sacrificing a Christian Child. From Schedel’s “Liber Chronicarum.” Nuremberg, 1493 | 58 |

| 13. | —Marginal Border. From Kerver’s “Psalterium Virginis Mariæ.” 1509 | 61 |

| 14. | —From Ovid’s “Metamorphoses.” Venice, 1518 (design, 1497). (Initial letter) | 65 |

| 15. | —The Creation. From the “Fasciculus Temporum.” Venice, 1484 | 68 |

| 16. | —Leviathan. From the “Ortus Sanitatis.” Venice, 1511 | 68 |

| 17. | —The Stork. From the “Ortus Sanitatis.” Venice, 1511 | 69 |

| 18. | —View of Venice. From the “Fasciculus Temporum.” Venice, 1484 | 69 |

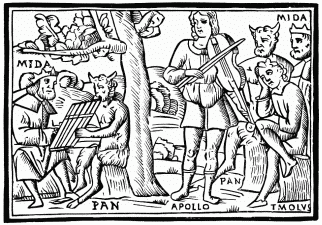

| 19. | —The Contest of Apollo and Pan. From Ovid’s “Metamorphoses.” Venice, 1518 (design, 1497) | 70 |

| 20. | —Sirens. From the “Ortus Sanitatis.” Venice, 1511 | 71 |

| 21. | —Pygmy and Cranes. From the “Ortus Sanitatis.” Venice, 1511 | 72 |

| 22. | —The Woman and the Thief. From “Æsop’s Fables.” Venice, 1491 (design, 1481) | 73 |

| 23. | —The Crow and the Peacock. From “Æsop’s Fables.” Venice, 1491 (design, 1481) | 75 |

| 24. | —The Peace of God. From “Epistole di San Hieronymo Volgare.” Ferrara, 1497 | 76 |

| 25. | —Mary and the Risen Lord. From “Epistole di San Hieronymo Volgare.” Ferrara, 1497 | 77 |

| 26. | —St. Baruch. From the “Catalogus Sanctorum.” Venice, 1506 | 77 |

| 27. | —Poliphilo by the Stream. From the “Hypnerotomachia Poliphili.” Venice, 1499 | 78 |

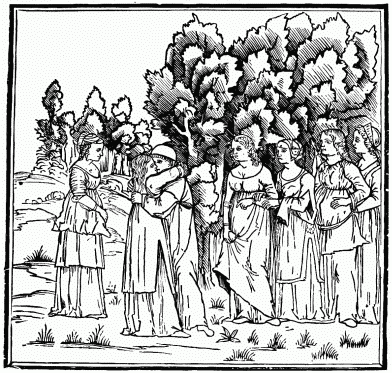

| 28. | —Poliphilo and the Nymphs. From the “Hypnerotomachia Poliphili.” Venice, 1499 | 79 |

| 29. | —Ornament. From the “Hypnerotomachia Poliphili.” Venice, 1499 | 80 |

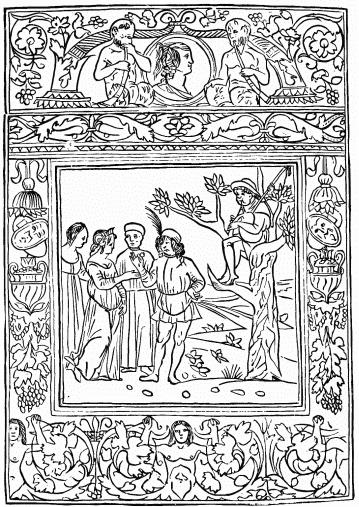

| 30. | —Poliphilo meets Polia. From the “Hypnerotomachia Poliphili.” Venice, 1499 | 81 |

| 31. | —Nero Fiddling. From the Ovid of 1510. Venice | 82 |

| 32. | —The Physician. From the “Fasciculus Medicinæ.” Venice, 1500 | 83 |

| 33. | —Hero and Leander. From the Ovid of 1515. Venice | 85 |

| 34. | —Dante and Beatrice. From the Dante of 1520. Venice | 86 |

| 35. | —St. Jerome Commending the Hermit’s Life. From “Epistole di San Hieronymo.” Ferrara, 1497 | 86 |

| 36. | —St. Francis and the Beggar. From the “Catalogus Sanctorum.” Venice, 1506 | 87 |

| 37. | —The Translation of St. Nicolas. From the “Catalogus Sanctorum.” Venice, 1506 | 87 |

| 38. | —Romoaldus, the Abbot. From the “Catalogus Sanctorum.” Venice, 1506 | 88 |

| 39. | —From an Italian Alphabet of the 16th Century. (Initial letter) | 90 |

| 40. | —St. John and the Virgin. Vignette to Dürer’s “Apocalypse” | 93 |

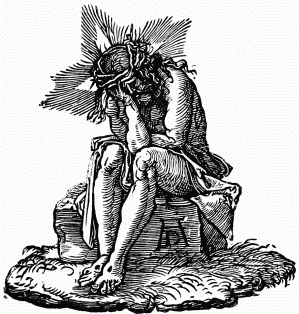

| 41. | —Christ Suffering. Vignette to Dürer’s “Larger Passion” | 94 |

| 42. | —Christ Mocked. Vignette to Dürer’s “Smaller Passion” | 95 |

| 43. | —The Descent into Hell. From Dürer’s “Smaller Passion” | 96 |

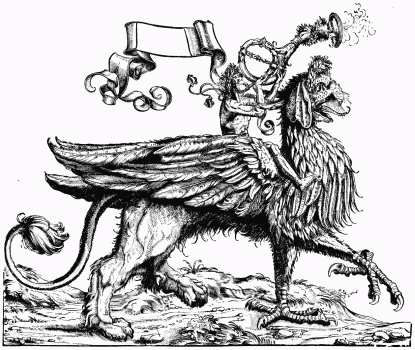

| 44. | —The Herald. From “The Triumph of Maximilian” | 100 |

| 45. | —Tablet. From “The Triumph of Maximilian” | 101 |

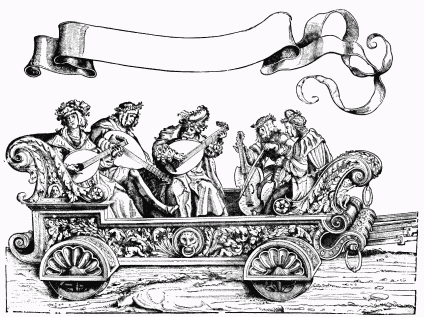

| 46. | —The Car of the Musicians. From “The Triumph of Maximilian” | 102 |

| 47. | —Three Horsemen. From “The Triumph of Maximilian” | 103 |

| 48. | —Horseman. From “The Triumph of Maximilian” | 107 |

| 49. | —Virgin and Child. From a print by Hans Sebald Behaim. | 113 |

| 50. | —From the “Epistole di San Hieronymo.” Ferrara, 1497. (Initial letter) | 116 |

| 51. | —The Nun. From Holbein’s “Images de la Mort.” Lyons, 1547 | 123 |

| 52. | —The Preacher. From Holbein’s “Images de la Mort.” Lyons, 1547 | 124 |

| 53. | —The Ploughman. From Holbein’s “Images de la Mort.” Lyons, 1547 | 125 |

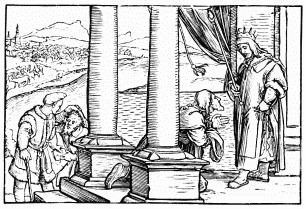

| 54. | —Nathan Rebuking David. From Holbein’s “Icones Historiarum Veteris Testamenti.” Lyons, 1547 | 130 |

| 55. | —From “Opera Vergiliana,” printed by Sacon. Lyons, 1517. (Initial letter) | 135 |

| 56. | —St. Christopher. From a Venetian print | 142 |

| 57. | —St. Sebastian and St. Francis. Portion of a print by Andreani after Titian | 143 |

| 58. | —The Annunciation. From a print by Francesco da Nanto | 144 |

| 59. | —Milo of Crotona. From a print by Boldrini after Titian | 145 |

| 60. | —From the “Comedia di Danthe.” Venice, 1536. (Initial letter) | 151 |

| 61. | —The Peacock. From Bewick’s “British Birds” | 156 |

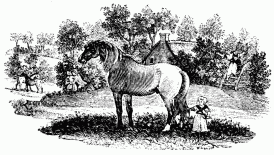

| 62. | —The Frightened Mother. From Bewick’s “British Quadrupeds” | 157 |

| 63. | —The Solitary Cormorant. From Bewick’s “British Birds” | 157 |

| 64. | —The Snow Cottage | 158 |

| 65. | —Birth-place of Bewick. His last vignette, portraying his own funeral | 158 |

| 66. | —The Broken Boat. From Bewick’s “British Birds” | 160 |

| 67. | —The Church-yard. From Bewick’s “British Birds” | 160 |

| 68. | —The Sheep-fold. By Blake. From “Virgil’s Pastorals” | 162 |

| 69. | —The Mark of Storm. By Blake. From “Virgil’s Pastorals” | 162 |

| 70. | —Cave of Despair. By Branston. From Savage’s “Hints on Decorative Printing” | 165 |

| 71. | —Vignette from “Rogers’s Poems.” London, 1827 | 167 |

| 72. | —Vignette from “Rogers’s Poems.” London, 1827 | 167 |

| 73. | —Death as a Friend. From a print by Professor Norton, of Cambridge. Engraved by J. Jungtow | 169 |

| 74. | —Death as a Throttler. From a print by Professor Norton, of Cambridge. Engraved by Steinbrecher | 170 |

| 75. | —The Creation. Engraved by J. F. Adams | 172 |

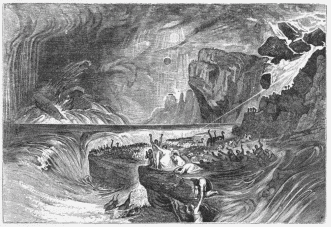

| 76. | —The Deluge. Engraved by J. F. Adams | 173 |

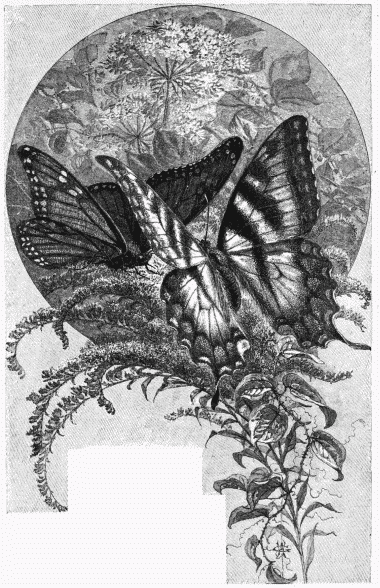

| 77. | —Butterflies. Engraved by F. S. King | 175 |

| 78. | —Spring-time. Engraved by F. S. King | 177 |

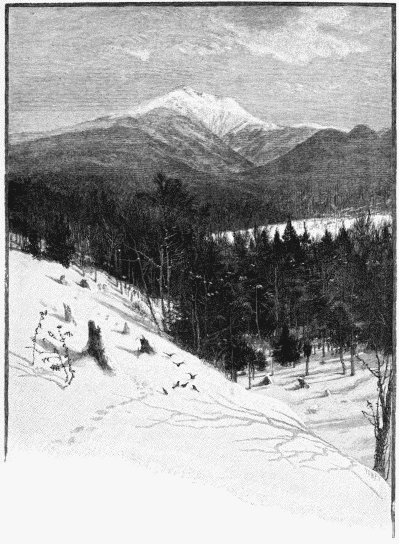

| 79. | —Mount Lafayette (White Mountains). By J. Tinkey | 183 |

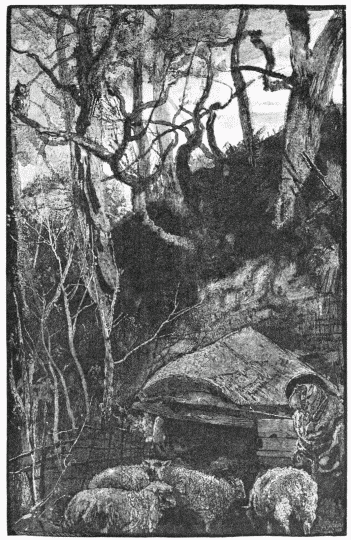

| 80. | —“And silent were the sheep in woolly fold.” Engraved by J. G. Smithwick | 187 |

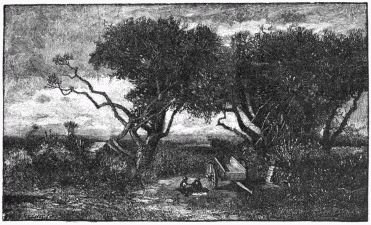

| 81. | —The Old Orchard. Engraved by F. Juengling | 189 |

| 82. | —Some Art Connoisseurs. Engraved by Robert Hoskin | 191 |

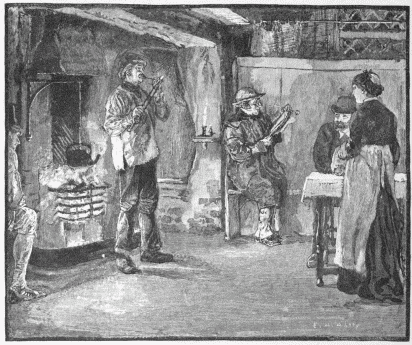

| 83. | —The Travelling Musicians. Engraved by R. A. Muller | 194 |

| 84. | —Shipwrecked. Engraved by Frank French | 196 |

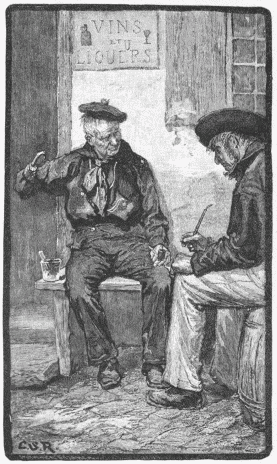

| 85. | —The Tap-room. Engraved by Frank French | 198 |

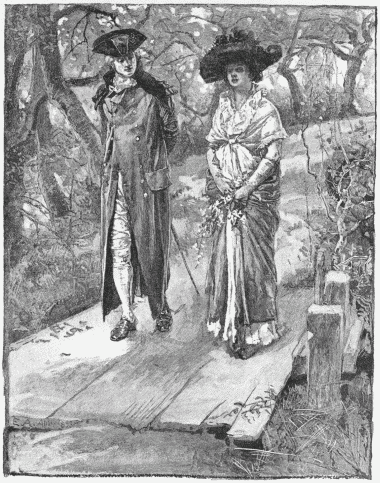

| 86. | —Going to Church. Engraved by J. P. Davis | 199 |

| 87. | —“Nay, Love, ’tis you who stand with almond clusters in your clasping hand.” Engraved by T. Cole | 201 |

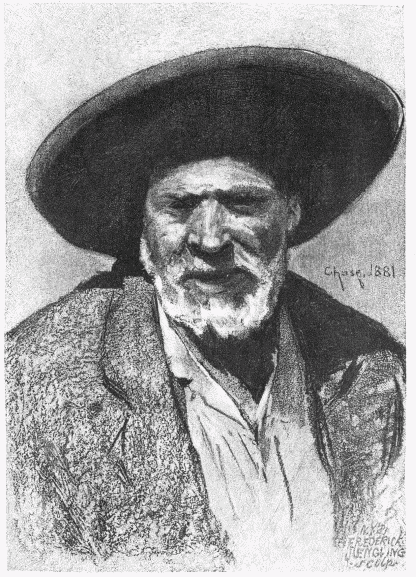

| 88. | —The Spanish Peasant. Engraved by F. Juengling | 203 |

| 89. | —James Russell Lowell. Engraved by Thomas Johnson | 205 |

| 90. | —Arthur Penrhyn Stanley. Engraved by G. Kruell | 207 |

FIG. 1.—From “Epistole di

San Hieronymo Volgare.”

Ferra 1497.HE beginning of the art of wood-engraving in Europe, the time when

paper was first laid down upon an engraved wood block and the first rude

print was taken off, is unknown; the name of the inventor and his

country are involved in a double obscurity of ignorance and fable,

darkened still more by national jealousies and vanities; even the

mechanical appliances and processes which led up to and at last resulted

in the new art, can only be conjectured. The art had long lain but just

beyond the border-line of discovery. The principle of making impressions

by means of lines cut in relief upon wood was known to the ancients, who

used engraved wooden stamps to indent figures and letters in soft

substances like wax and clay, and, possibly, to print colors on

surfaces, as had been done from early times in India in the manufacture

of cloth; similar stamps were used in the Middle Ages by notaries and

other public officers to print signatures on documents, by Italian

cloth-makers to impress colors on silk and other fabrics, and by the

illuminators of manuscripts to strike the outlines of initial letters.

This practice may have suggested the new process.

It is more probable that the art began in the workshops of the goldsmiths, who were so skilled in engraving upon metal that impressions of much artistic value have been taken from work executed by them in the twelfth century, showing that they really were engravers obliged to remain goldsmiths, because the art of printing from metal plates was unknown.[1] By their knowledge of design and their artistic execution, at least, if not by their mechanical inventiveness, the goldsmiths were the lineal ancestors of the great engravers of the Renaissance. Their art had been continued from Roman times, with fewer interruptions and hinderances than any other of the fine arts. It was early employed in the adornment of the altar, the pax, and other articles of the Church service; already, in St. Bernard’s time, so much attention was given to workmanship of this kind, and so much wealth lavished upon it, that he denounced it, with true ascetic spirit, as a decoration of what was soon to become vile, a waste of what might have been given to the poor, and a distraction of the spirit from holiness to the admiration of beauty. “The Church,” he said, “shines with the splendor of her walls, and among her poor is destitution; she clothes her stones with gold, and leaves her children naked. * * * Finally, so many things are to be seen, everywhere such a marvellous variety of different forms, that one may read more upon the sculptured walls than in the written Scriptures, and spend the whole day in going about in wonder from one such thing to another, rather than in meditating upon God’s law.”[2] The art might have suffered seriously from such uncompromising opposition as St. Bernard made, had not Suger, the great abbot of St. Denys, taken up its defence and supported it by his patronage and by his eloquence. “Let each one have his own opinion,” he writes, “but I confess it is my conviction that whatever is most precious ought to be devoted above all to that holiest rite of the Eucharist; if golden lavers, if golden cups, and if golden bowls were used, by the command of God or of the prophet, to catch the blood of rams or bullocks or heifers, how much more ought vases of gold, precious stones, and whatever is dearest among all creatures, ever to be set forth with full devotion to receive the blood of Jesus Christ!”[3] By such arguments Suger defended the rightfulness and value of the goldsmith’s art in the service of the Church. After his time the employment of the goldsmiths upon church decoration became so great that they were really the artists of Europe during the two hundred years previous to the invention of wood-engraving.[4] In the pursuit of their craft they practised the arts of modelling, casting, sculpture, engraving, enamelling, and the setting of precious stones; and in the thirteenth century they made use of all these resources in the execution of their beautiful works of art made of gold and silver, richly engraved, and adorned with bass-reliefs and statuettes, and brilliant with many-colored enamel and with jewels—the reliquaries in which were kept the innumerable holy relics that then filled Europe, the famous shrines for the bodies of the saints, about which pilgrims from every quarter were ever at prayer, and the tombs of the Crusaders, and of dignitaries of Church or State. They employed their skill, too, for the lesser glory of the churches, upon the vessels of the Holy Communion, the crosses, candelabra, and censers, and the ornaments that incrusted the vestments of the priests. With the increase of luxury and wealth they found a new field for their invention in contributing to the magnificence of secular life; in fashioning into strange forms the ewers, goblets, flagons, and every vessel which adorned the banquet; and in ornamenting them with fantastic figures, or with scenes from the chase, or from the history of Charlemagne and Saladin, as well as in executing those finely wrought decorations with which the silks and velvets of the nobles were so heavily charged that the old poet, Martial d’Auvergne, says the lords and knights were “caparisoned in gold-work and jewels.” Under Charles V. of France (1364) and the great Dukes of the Low Countries, the jewel-chamber of the prince was his pride in peace and his treasury in war: it furnished gifts for the bride, the favorite, and the heir, and for foreign ambassadors and princes; it afforded pay for retainers before the battle and ransom after it, and in the days of the great fêtes its treasures gave to the courts of France, Burgundy, and Flanders a magnificence that has seldom been seen in Europe.[5]

Under such fortunate encouragement the goldsmiths of the fourteenth century reached a knowledge of design and a finish in execution that justified the claim of their art to the first place among the fine arts, and made their workshops the apprentice-home of many great masters of art in Italy as well as in the North. They best understood the value of art, and were best skilled in artistic processes; they were the only persons[6] who had by them all the means for taking an impression—the engraved metal plate, iron tools, burnishers for rubbing off a proof, blackened oil, and paper which they used for tracing their designs; they would, too, have been aided in their art, merely as goldsmiths, could they have tested their engraving from time to time by taking an impression from it in its various stages. It is not unlikely, therefore, that the art of taking impressions from engraved work was found out, or at least was first extensively applied, in their workshops, where it could hardly have failed to be discovered ultimately, as paper came into use more generally and for more various purposes. If this were the case, metal-engraving preceded wood-engraving, but only by a brief space of time, because, as soon as the idea of the new art was fully grasped, wood must have been almost immediately employed in preference to metal, on account of the greater ease and speed of working in wood, and of the less injury done to the paper in printing from it.

Some support for this view, that the art of printing from engraved metal plates was discovered by the goldsmiths, and preceded and suggested wood-engraving, is derived from the peculiar prints in the manière criblée, or the dotted style, of which over three hundred are known. They were produced by a mixed process of engraving in relief and in intaglio, usually upon a metal plate, but sometimes upon wood. The effects are given by dots and lines relieved in white upon a black ground, assisted by dots and lines relieved in black upon a white ground. These prints have afforded much material for dispute and controversy, both as to their process and their date; the mode in which the metal plates from which they were printed were engraved, particularly the punching out small holes in the metal, which appear usually as white dots, and give the name to the prints, is the same as a mode of ornamental work[7] in metal that had been practised for centuries in the workshops of the goldsmiths, and on this account they have been ascribed to the goldsmiths of the great Northern cities.[8] They appeared certainly as early as 1450, and probably much earlier.[9] Some of these prints are evidently taken from metal plates not originally meant to be printed from, for the inscriptions on the prints as well as the actions of the figures appear reversed, the words reading backward, and the figures performing actions with the left hand almost always performed by the right hand.[10] These may be the work of the first years of the fifteenth century, or they may have been taken long afterward, in a spirit of curiosity or experiment. The existence of these early prints, however, undoubtedly from the workshops of the goldsmiths, and after a mode long practised by them, strengthens the hypothesis—suggested by their wide acquaintance with artistic processes and their exclusive possession of all the proper instruments—that they originated the art of taking impressions on paper from engraved work; at all events, this seems the least wild, the most consistent, and best supported conjecture which has been put forth.

There is, however, no lack of more specific accounts of the origin of wood-engraving. Pliny’s[11] reference to the portraits with which Varro illustrated his works indicates, in the opinion of some writers, a momentary, isolated, and premature appearance of the art in his day. Ottley[12] maintains that the art was introduced into Europe by the Venetians, who learned it “at a very early period of their intercourse with the people of Tartary, Thibet, and China;” but of this there is no satisfactory evidence. Papillon,[13] a French engraver of the last century, relates that in his youth he saw in the library of a retired Swiss officer nine woodcuts, illustrative of the deeds of Alexander the Great, executed with a small knife by “two young and amiable twins,” Isabella and Alexander Alberico Cunio, Knt., of Ravenna, in their seventeenth year, and dedicated by them to Pope Honorius IV., in 1284-85; but, as no one else ever saw or heard of them, and there is no contemporary reference to them, as no single unquestionable fact has been adduced in direct support of the story, and as Papillon is an untrustworthy writer, his tale, although accepted by some authorities,[14] is generally discredited,[15] and was regarded by Chatto[16] as the hallucination of a distempered mind. Meerman,[17] the stout defender of the claim of Lawrence Coster to the invention of printing with movable types, relying on the authority of Junius,[18] who wrote from tradition more than a century after the facts, makes Coster the first printer of woodcuts. Some writers accept this story; but in spite of them, and of the well-developed genealogical tree with which Meerman provided his hero, and even of Mr. Sotheby’s[19] supposed discovery of Coster’s portrait, his very existence is doubted. The charming scene in which the idea of the new art first occurred to Coster, as he was walking after dinner in his garden, and cutting letters from beech-tree bark with which to print moral sentences for his grandchildren—the old man surrounded by the childish group in the well-ordered Haarlem garden—is probably, after all, little more than a play of antiquarian fancy. These stories have slight historic weight; they are, to use M. Renouvier’s simile, “a group of legends about the cradle of modern art, like those recounted of ancient art, the history of Craton, of Saurias, or of the daughter of Dibutades, who invented design by tracing on a wall the silhouette of her lover.”

FIG. 2.—St. Christopher, 1423. From Ottley’s “Inquiry

into the Origin and Early History of Engraving upon Copper and in

Wood.”

The first fact known with certainty in the history of wood-engraving is, that in the first quarter of the fifteenth century there were scattered abroad in Northern Europe rude prints, representing scenes from the Scriptures and the lives of the saints. These pictures were on single leaves of paper; the outlines were printed from engraved wood-blocks, but occasionally, it is believed, from metal plates cut in relief; they were taken off in a pale, brownish ink by rubbing on the back of the paper with a burnisher, and sometimes in black ink and with a press; they were then colored, either by hand or by means of a stencil plate, in order to make them more attractive to the people. The earliest of these prints which bears an unquestionable date is the famous St. Christopher (Fig. 2) of 1423, found by Heinecken,[20] in the middle of the last century, pasted inside the cover of a manuscript in the library of the convent of Buxheim, in Suabia. It represents St. Christopher, according to a favorite legend of the Middle Ages, fording a river with the infant Christ upon his shoulders; opposite, on the right bank, a hermit holds a lantern before his cell; on the left a peasant, with a bag on his back, climbs the steep ascent from his mill to the cottage high up on the cliff, where no swelling of the stream will reach it. The attitude of the two heads is expressive, and the folds of the saint’s robes are well cast about the shoulders; in other respects the cut has little artistic merit, but the attempt to mark shadows by a greater or less width of line is noticeable, and the lines in general are much more varied than is usual in early work. It was printed in black ink, and with a press. There are two other early prints, the dates of which are uncertain, but still sufficiently probable to deserve mention—the warmly controverted Brussels print[21] of 1418, which represents the Virgin and Child, surrounded by four saints, in an enclosed garden, in the style of the Van Eycks, and with more artistic merit than the St. Christopher in design, drawing, and execution; and, secondly, the St. Sebastian of 1437, at Vienna. The former was discovered in 1844, in a bad condition, and the latter in 1779; both are taken off in pale ink, and with a rubber. There are numerous other prints of this kind, which have been described in detail and have had conjectural dates assigned to them, fruitful of much antiquarian dispute. One of these (Fig. 3) is here reproduced for the first time; it was found stitched into a manuscript of 1445, and is unquestionably as old as the manuscript; it represents a Crucifixion, with the Virgin and Longinus at the left, and St. John and, perhaps, the Centurion at the right; in the upper left-hand corner is an angel with the Veronica, or handkerchief, which bears the miraculous portrait of the Saviour, and above are a scourge and a knife; in the original the body of Christ is covered with dots and scratches in vermillion, to represent blood. It was taken off in black ink with a press, and is one of the rudest engravings known.[22]

FIG. 3.—The Crucifixion. From the Manuscript “Book of

Devotion.” 1445.

Valueless as these prints[23] are, for the most part, as works of art, they are of great interest. They were the first pictures the common people ever had, and doubtless they were highly prized. Rude as they were, the poor German peasant or humble artisan of the great industrial cities cared for them; they had been given to him by the monks, like the rudely-carved wooden images of earlier times, at the end of some pilgrimage that he had made for penance or devotion, and were treasured by him as a precious memento; or some preaching friar, to whom he had devoutly given a small alms for the building of a church or the decoration of a shrine, had rewarded his piety with a picture of the saint whom, so far as he could, he had honored; or he had received them on some day of festival, when in the streets of the Flemish cities the Lazarists or other orders of monks had marched in grand procession, scattering these brilliantly colored prints among the populace. Stuck up on the low walls of his dwelling, they not only recalled his pious deeds, they brought home before his eyes in daily sight the reality of that holy living and holy dying of the Saviour and his martyrs in whose intercession and prayer his hope of salvation lay. Throughout the fifteenth and a part of the sixteenth centuries, although the intellectual life of the higher classes began to be secularized, among the common people these mediæval sentiments and customs, which gave rise to the holy prints, continued without change until the Reformation; and so the workshops of the monks and of the guilds of Augsburg, Nuremberg, Ulm, Cologne, and the Flemish cities, kept on issuing these saints’ images, as they were called, long after the art had produced refined and noble works. They remained, in accordance with the true mediæval spirit, not only without the name of the craftsman, nomen vero auctoris humilitate siletur, but unmarked by any individuality, impersonal as well as anonymous; there is little to show even the difference in the time and place of their production, except that their lines in the first half of the century were more round and flowing, while in the latter half they were angular, after the manner of the Van Eycks, and that they vary in the choice and brilliancy of their colors.[24]

At the very beginning, too, wood-engraving was applied to a new industry, which had sprung up rapidly, to furnish amusement for the camp and the town—the manufacture of playing-cards. Some writers have maintained that the art was thus applied before it was employed to make the holy prints; but there are no playing-cards known to have been printed before 1423, and it is probable that they were painted by hand and adorned by the stencil for some time after the first unquestioned mention of them in 1392.[25] The manufacture of both cards and holy prints soon became a thriving trade; it is mentioned in Augsburg in 1418, and soon afterward in Nuremberg; and in 1441 the exportation of these articles into Italy had become so large that the Venetian Senate passed a decree,[26] which is the earliest document relative to wood-engraving in Italy, forbidding their importation into Venice, because the guild engaged in this manufacture in the city was suffering from the foreign competition. Wood-engraving, being only one process in the craft of the card-maker and the print-maker, seems to have remained without a distinct name for a long while after its invention.

In the middle of the fifteenth century, therefore, wood-engraving, the youngest of the arts of design, after fifty years of obscure and unnoticed history, held an established position, and was recognized as a new craft. In art its discovery was the parallel of the invention of printing in literature; it was a means of multiplying and spreading the ideas which are expressed by art, of creating a popular appreciation and knowledge of art, and of bringing beautiful design within the reach of a larger body of men. It is difficult for a modern mind to realize the place which pictures filled in mediæval life, before the invention of printing had brought about that great change which has resulted in making books almost the sole means of education. It was not merely that the paintings upon the walls of the churches conveyed more noble conceptions to the peasant and the artisan than their slow imagination could build up out of the words of the preacher; like children, they apprehended through pictures, they thought upon all higher themes in pictures rather than in words; their ideas were pictorial rather than verbal; painting was in spiritual matters more truly a language to them than their own patois. They could not reason, they could not easily understand intellectual statement, they could not imagine vividly, they could only see. This accounts for the rapid spread of the new art, and for the popularity and utility of the holy prints which were so widely employed to convey religious ideas and quicken religious sentiment; in the production of these wood-engraving appears from the first in its true vocation as a democratic art in the service of the people; its influence was one, and by no means the most insignificant, of the great forces which were to transform mediæval into modern life, to make the civilization of the heart and the brain no longer the exclusive possession of a few among the fortunately born, but a common blessing. Wood-engraving was at once the product of the desire for this change and of the effort toward it, a mirror of the movement the more valuable because the art was more intimately connected with the popular life than any other art of the Renaissance, and a power feeding the impulse from which it derived its own vitality. In this fact lies the historic interest of the art to the student of civilization. At first it served mediæval religion; afterward it took a wider range, and by both its serious and satirical works afforded valuable aid in the progress of the Reformation, while it rendered the earliest printed books more attractive, in which its nobler designs educated the eye in the perception of beauty. Finally, in the hands of the great engravers—of Dürer, who, still mastered by the mediæval spirit, employed it to embody the German Renaissance; of Maximilian’s artists, who recorded in it the dying picturesqueness and chivalric spirit of the Middle Ages; of Holbein, who first heralded, by means of it, the intelligence and sentiment of modern times—it produced its chief monuments, which, for the most part, will here be dealt with, in order to illustrate its value as a fine art practised for its own sake, as a trustworthy contemporary record of popular customs, ideas, and taste, and as an element of considerable power in the advancement of modern civilization.

FIG. 4.—From the “Epistole

di San Hieronymo.” 1497.URING the first half of the fifteenth century, in more than one quarter

of Europe, ingenious minds were at work seeking by various experiments

and repeated trials, with more and more success, the great invention of

printing with movable types; even now, after the most searching inquiry,

the time and place of the invention are uncertain. Printing with movable

types, however, was preceded and suggested by printing from engraved

wood-blocks. The holy prints sometimes bore the name of the saint, or a

brief Ora pro nobis or other legend impressed upon the paper; the

wood-engravers who first cut these few letters upon the block, although

ignorant of the vast consequences of their humble work, began that great

movement which was to change the face of civilization. After letters had

once been printed, to multiply the words and lengthen the sentences, to

remove them from the field of the cut to the space below it, to engrave

whole columns of text, and, finally, to reproduce entire manuscripts,

and thus make printed books, were merely questions of manual skill and

patience. Where or when or by whom these block-books, as they are

called, were first engraved and printed is unknown; these questions have

been bones of contention among antiquarians for three hundred years, and

in the dispute much patient research has been expended, and much dusty

knowledge heaped together, only to perplex doubt still farther, and to

multiply baseless conjectures. It is probable that they were produced in

the first half of the fifteenth century, when the men of the

Renaissance, whose aroused curiosity made them alert to seize any new

suggestion, were everywhere seeking for means to overthrow the great

barrier to popular civilization, the rarity of the instruments for

intellectual instruction; they soon saw of what service the new art

might be in this task, through the cheapness and rapidity of its

processes, and they applied it to the printing of words as well as of

pictures.

The most common manuscripts of the time, which had hitherto been the cheapest mode of intellectual communication, were especially fitted to be reproduced by the new art; they were those illustrated abridgments of Scriptural history or doctrine, called Biblia Pauperum, or books of the poor preachers, which had long been used in popular religious instruction, in accordance with the mediæval custom of conveying religious ideas to the illiterate more quickly and vividly through pictures than was possible by the use of language alone. In the sixth century Gregory the Great had defended wall-paintings in the churches as a means of religious instruction for the ignorant population which then filled the Roman provinces. In a letter to the Bishop of Marseilles, who had shown indiscreet zeal in destroying the pictures of the saints, he wrote: “What writing is to those who read, that a picture is to those who have only eyes; because, however ignorant they are, they see their duty in a picture, and there, although they have not learned their letters, they read; wherefore, for the people especially, painting stands in the place of literature.”[27] In conformity with this opinion these manuscripts were composed at an early period; they were written rapidly by the scribes, and illustrated with designs made with the pen, and rudely colored by the rubricators. They served equally to take the place of the Bible among the poor clergy—for a complete manuscript of the Scriptures was far too valuable a treasure to be within their reach—and to aid the people in understanding what was told them; for, doubtless, in teaching both young and old the monks showed these pictures to explain their words, and to make a more lasting impression upon the memory of their hearers. These designs, it is worth while to point out, exhibit the immobility of mind in the mediæval communities, guided, as they were, almost wholly by custom and tradition; the designs were not original, but were copied from the artistic representations in the principal churches, where the common people may have seen them, when upon a pilgrimage or at other times, carved among the bass-reliefs or glowing in the bright colors of the painted windows. They were copied without change, the scenes were conceived in the same manner, the characters were represented after the same conventional type, even in the details there was slight variation; and as the decorative arts in the churches were subordinated to architecture, these designs not infrequently bear the stamp of their original purpose, and are marked by the characteristics of mural art. They were copied, too, not only by the scribes from early representations, but they were reproduced by the great masters of the Renaissance from the manuscripts and block-books themselves; Dürer, Quentin Matzys, Lukas van Leyden, Martin Schön, and, in earlier times, Taddeo Gaddi and Orcagna, took their conceptions from these sources.

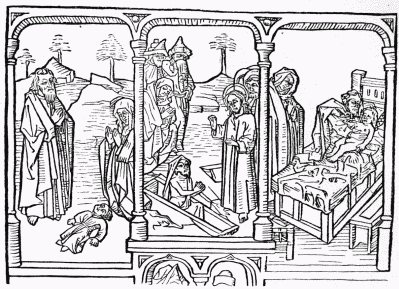

Of the block-books which reproduced these and similar manuscripts several have been preserved, and some of them have been reproduced in fac-simile, and minutely described. Among the most important of these, the Biblia Pauperum,[28] or Poor Preachers’ Bible, of which copies of several editions exist, deserves to be first mentioned. It is a small folio, containing forty pages, printed upon one side only, with the pale brownish ink used in most early prints, and by means of a rubber. The pages are arranged so that they can be pasted back to back; each page is divided into five compartments, separated by the pillars and mouldings of an architectural design, which immediately recall the divisions of a church window; in the centre is depicted some scene (Fig. 5) from the Gospels, and on either side are placed scenes from the Old Testament history illustrative or typical of that commemorated in the central design; both above and below are two half-length representations of holy men. Various texts are interspersed in the field, and Latin verses are written below the central compartments. It will be seen that the designs not only served to illustrate the preacher’s lesson, but suggested his subject, and indicated and directed the course of his sermon: they taught him before they taught the people.

Elijah Raiseth the Widow’s Son (1 K, xvii.). The Raising

of Lazarus (Jno, xi.). Elisha Raiseth the Widow’s Son (2 K. iv.).

FIG. 5.—From the original in the possession of Professor Norton, of

Cambridge.

FIG. 6.—The Creation of Eve. From the fac-simile of

Berjeau.

But, before commenting on this volume, it will be useful to describe first the much more interesting and more famous Speculum Humanæ Salvationis,[29] or Mirror of Human Salvation, an examination of which will throw light on the history of the art. It is a small folio, and contains sixty-three pages, printed upon one side, of which fifty-eight are surmounted by two designs enclosed in an architectural border, which are illustrative or symbolical of the life of Christ or of the Virgin; the designs (Fig. 6) are printed in pale ink by means of a rubber. The text is not engraved on the block or placed in the field of the cut, but is printed from movable metallic type in black ink with a press, and occupies the lower two-thirds of the page, in double columns. The book is, therefore, a product of the two arts of wood-engraving and typography in combination. There are four early editions known, two in Latin, and two in Dutch, all without the name of the printer, or the date or place of publication. They are printed on paper of the same manufacture, with woodcuts from the same blocks, and in the same typographical manner, excepting that one of the Latin editions contains twenty pages in which the text is printed from engraved wood-blocks in pale brownish ink, and with a rubber, like the designs. These four editions, therefore, were issued in the same country.

This curious book has been the subject of more dispute than any other of the block-books, because it offers more tangible facts to the investigator. The type is of a peculiar kind, distinctly different from that used by the early German printers, and the same in character with that used in other early books undoubtedly issued in the Low Countries. The language of the Dutch editions is the pure dialect of North Holland in the first part of the fifteenth century; the costumes, the short jackets, the high, broad-brimmed hats, sometimes with flowing ribbons, the close-fitting hose and low shoes of the men, the head-dresses and skirts of the women, are of the same period in the Netherlands, and even in the physiognomy of the faces Flemish features have been seen. The designs, too, are in the manner of the great Flemish school, renowned as the best in Europe outside Italy, which was founded by Van Eyck, the discoverer of the art of painting in oil, and which was marked by a realism altogether new and easily distinguished; the backgrounds are filled with architecture of the same time and country. The Speculum, therefore, was produced in the Low Countries; it must have been printed there before 1483, and probably was printed some time before 1454. The Biblia Pauperum has so much in common with the Speculum in the style of its art, its costumes, and its general character, that, although of earlier date, it may be unhesitatingly ascribed to the same country.

The internal evidence, however, only enforces the probabilities springing from the social condition of the Netherlands, then the most highly civilized country north of the Alps. Its industries, in the hands of the great guilds of Bruges, Ghent, Brussels, Louvain, Antwerp, and Liege, were the busiest in Europe. Its commerce was fast upon the lagging sails of Venice. The “Lancashire of the Middle Ages,” as it has been fitly called, sent its manufactures abroad wherever the paths of the sea had been made open, and received the world’s wealth in return. The magnificence of its Court was the wonder of foreigners, and the prosperity of its people their admiration. The confusion of mediæval life, it is true, was still there—fierce temper in the artisans, blood-thirstiness in the soldiery, everywhere the pitilessness of military force, wielded by a proud and selfish caste, as Froissart and Philippe de Comyns plainly recount; but there, nevertheless—although the brutal sack of Liege was yet to take place—modern life was beginning; merchant-life, supported by trade, citizen-life, made possible by the high organization of the great guilds, had begun, although the merchant and the citizen must still wear the sword; art, under the guidance of the Van Eycks, was passing out of mediæval conventionalism, out of the monastery and the monkish tradition, to deal no longer with lank, meagre, martyr-like bodies, to care no more for the moral lesson in contempt of artistic beauty, to come face to face with nature and humanity as they really were before men’s eyes; and modern intellectual life, too—faint and feeble, no doubt—was nevertheless beginning to show signs of its presence there, where in after-times great thinkers were to find a harbor of refuge, and the most heroic struggle of freedom was to be fought out against Spain and Rome. This comparatively high state of civilization, the activity of men’s minds, the variety of mechanical pursuits, the excellence of the goldsmiths’ art, the number and character of the early prints undoubtedly issued there, the mention of incorporated guilds of printers at Antwerp as early as 1417, and again in 1440, and at Bruges in 1454, make it probable that the invention of wood-engraving was due to the Netherlands, and perhaps the invention of typography also. Whether this were the case or not, it is certain that the artists of the Netherlands carried the art of engraving in wood to its highest point of excellence during its first period.

Antiquarians have not been contented to show that the best of the block-books came from the Netherlands; they have attempted to discover the names of the composer of the Speculum, the engraver of its designs, and its printer. But their conjectures[30] are so doubtful that it is unnecessary to examine them, with the exception of the ascription of the printing of the Speculum to the Brothers of the Common Lot.[31] This brotherhood was one of the many orders which arose at that time in the Netherlands, given to mysticism and enthusiasm, that resulted in real licentiousness; or to piety and reform, that prepared the way for the Reformation. Its members were devoted to the spread of knowledge, and were engaged in copying manuscripts and founding public schools in the cities. After the invention of printing, they set up the first presses in Brussels and Louvain, and published many books, always, however, without their name as publishers. They practised the art of wood-engraving, and doubtless some of the early holy prints were from their workshops; sometimes they inserted woodcuts in their manuscripts, as in the Spirituale Pomerium, or Spiritual Garden, of Henri van den Bogaerde, the head of the retreat at Groenendael, where the painter Diedrick Bouts occasionally sought retirement, and where he may have aided the Brothers with his knowledge of design. It is quite possible that this brotherhood, so favorably placed, produced the Speculum and others of the block-books, and that they were aided by the painters of the time whose style of design they followed; but, as Renouvier remarks in rejecting this account, the monks were not the only persons too little desirous of notoriety to print their names, and although they took part in early engraving and printing, a far more important part was taken by the great civil corporations. In either case, whether the monks or the secular engravers designed these woodcuts, they were probably aided at times by the painters, who at that period did not restrict themselves to the higher branches of art, but frequently put their skill to very humble tasks.

The character of the design is very easily seen; the lines are simple, often graceful and well-arranged; there is but little attempt at marking shadows; there is less stiffness in the forms, and the draperies follow the lines of the forms better than in either earlier or later work of a similar kind, and there is also much less unconscious caricature and grimace. A whole series needs to be looked at before one can appreciate the interest which these designs have in indicating the subjects on which imagination and thought were then exercised, and the modes in which they were exercised. Symbolism and mysticism pervade the whole. All nature and history seem to have existed only to prefigure the life of the Saviour: imagination and thought hover about him, and take color, shape, and light only from that central form; the stories of the Old Testament, the histories of David, Samson, and Jonah, the massacres, victories, and miracles there recorded, foreshadow, as it were in parables, the narrative of the Gospels; the temple, the altar, and the ark of the covenant, all the furnishings and observances of the Jewish ritual, reveal occult meanings; the garden of Solomon’s Song, and the sentiment of the Bridegroom and the Bride who wander in it, are interpreted, sometimes in graceful or even poetic feeling, under the inspiration of mystical devotion; old kings of pagan Athens are transformed into witnesses of Christ, and, with the Sibyl of Rome, attest spiritual truth. This book and others like it are mirrors of the ecclesiastical mind; they picture the principal intellectual life of the Middle Ages; they show the sources of that deep feeling in the earlier Dutch artists which gave dignity and sweetness to their works. Even in the rudeness of these books, in the texts as well as in the designs, there is a naïveté, an openness and freshness of nature, a confidence in limited experience and contracted vision, which make the sight of these cuts as charming as conversation with one who had never heard of America or dreamed of Luther, and who would have found modern life a puzzle and an offence. The author of the Speculum laments the evils which fell upon man in consequence of Adam’s sin, and recounts them: blindness, deafness, lameness, floods, fire, pestilence, wild beasts, and lawsuits (in such order he arranges them); and he ends the long list with this last and heaviest evil, that men should presume to ask “why God willed to create man, whose fall he foresaw; why he willed to create the angels, whose ruin he foreknew; wherefore he hardened the heart of Pharaoh, and softened the heart of Mary Magdalene unto repentance; wherefore he made Peter contrite, who had denied him thrice, but allowed Judas to despair in his sin; wherefore he gave grace to one thief, and cared not to give grace to his companion.” What modern man can fully realize the mental condition of this poet, who thus weeps over the temptation to ask these questions, as the supreme and direst curse which Divine vengeance allows to overtake the perverse children of this world?

A better illustration of the sentiment and grace sometimes to be found in the block-books is the Historia Virginis Mariæ ex Cantico Canticorum, or History of the Virgin, as it is prefigured in the Song of Solomon. This volume is the finest in design of all the block-books. In it the Bride, the Bridegroom, three attendant maidens, and an angel are grouped in successive scenes, illustrating the mystical meaning of some verse of the Song. The artistic feeling displayed in the arrangement of the figures is such that the designs have been attributed directly to Roger Van der Weyden, the greatest of Van Eyck’s pupils. This book, like the Biblia Pauperum and the Speculum, came from the engravers and the printers of the Netherlands; but it shows progress in art beyond those works, more elegance and vivacity of line, more ability to render feeling expressively, and especially more delight in nature and carefulness in delineating natural objects.

In spite of these three chief monuments of the art of block-printing in the Netherlands, the claim of that country to the invention of the block-books is not undisputed. The Historia Johannis Evangelistæ ejusque Visiones Apocalypticæ, or the Apocalypse of St. John, much ruder in drawing and in execution, is the oldest block-book according to most writers, and especially those who maintain the claims of Germany to the honor of the invention. This volume has been ascribed by Chatto to Upper Germany, where some Greek artist may have designed it; but with more probability, by Passavant, to Lower Germany, and especially to Cologne, on account of the coloring, which is in the Cologne manner. The volume bears a surer sign of early work than mere rudeness of execution: it is hieratic rather than artistic in character; the artist is concerned more with enforcing the religious lesson than with designing pleasant scenes. But although for this reason a very early date (1440-1460) must be assigned to the book, the question of the origin of the art of block-printing remains unsettled, even if it be granted that the volume is of German workmanship. Some evidence must be shown that the Netherlands imported the art from Cologne or some other German city, and this is lacking; indeed, the absence in early Flemish work of any trace of influence from the school of art which flourished at Cologne before the Van Eycks painted in the Netherlands, is strong negative evidence against such a supposition. On the other hand, it must be remembered that Germany produced the St. Christopher, and many other early prints. In some of the German block-books Heinecken recognized the modes of the German card-makers; but this may be explained otherwise than by supposing that the card-makers invented the art of block-printing. On the whole, the rudeness of early German block-books must be held to be a result of the unskilfulness and tastelessness of German workmen, rather than an indication that the art was discovered by them. The engraving of the Apocalypse, like all other German work, will bear no comparison with the Netherland engraving, either in refinement, vivacity, or skill.

The other block-books, many of which are in themselves interesting and curious, do not elucidate the history of the art, and therefore need not be discussed. It is sufficient to say that they are less valuable than those which have been described, and far ruder in design and execution. Some of them throw light upon the time. The Ars Memorandi, a series of designs meant to assist the memory in recalling the chapters of the Apocalypse, is a very curious monument of an age when such a device was useful; and the Ars Moriendi, or Art of Dying, in which were depicted frightful and eager devils about a dying man’s couch, is a book which may stir our laughter, but was full of a different meaning for the poor sinner to whose bedside the pious monks carried it to bring him to repentance, by showing him designs of such horrible suggestion, enforced, no doubt, by exhortations hardly more humane. These books were all reproduced many times. This Art of Dying, for example, appeared in Latin, Flemish, German, Italian, French, and English, with similar designs, although there were variations in the text. Once popular, they have long since lost their attraction; few care for the ideas or the pictures preserved in them; the bibliophile collects them, because they are rare, costly, and curious; the scholar consults them, because they reveal the unprofitableness of mediæval thought, the needs and characteristics of the class that could prize them, the poverty of the civilization of which they are the monuments, and because they disclose glimpses of actual human life as it then was, with its humors, its burdens, and its imaginations. The world has forgotten them; but they hold in the history of civilization an honorable place, for by means of them wood-engraving led the way to the invention of printing, and thereby performed its greatest service to mankind.

FIG. 7.—Source of this letter

unknown.N 1454 the art of printing in movable types and with a press had been

perfected in Germany; soon afterward the art of block-printing, although

it continued to be practised until the end of the century, began to fall

into decay, and the ancient block-books, in which the text had been

subsidiary to the colored engravings, speedily gave place to the modern

printed book, in which the engravings were subsidiary to the text. This

change did not come about without a struggle between the rival arts. In

all the great cities of Germany and the Low Countries, the

block-printers and wood-engravers had long been organized into strong

and compact guilds, enforcing their rights with strict jealousy, and

privileged from the first to make use of movable types and the press;

the new printers, on the other hand, were comparatively few in number,

disunited and scattered, accustomed to go from one town to another, and

every attempt by them to insert woodcuts into their books was looked

upon and resented as an encroachment on the art of the block-printers

and the wood-engravers. At first the new printers closely imitated the

manuscripts of their time. They used woodcuts to take the place of the

miniatures with which the manuscripts were embellished. They copied

directly the handwriting of the scribes in the forms of their type, and

were thus led to the use of ornamental initial letters like those which

had long been designed by the scribes and illuminated by the

rubricators; such are the beautiful initial letters in the Psalter of

Faust and Scheffer, published at Mayence in 1457, which are the earliest

wood-engravings in a dated book, and are designed and executed with a

skill which has rarely been surpassed. It was by such attempts that the

new printers incurred the hostility of the wood-engravers, which was

soon actively shown. Even as late as 1477, the guild at Augsburg, which

was then the most numerous and best-skilled in Germany, opposed the

admission of Gunther Zainer, who had just set up a printing-press there,

to the rights of citizenship, and he owed his freedom from molestation

to the interference of the friendly abbot, Melchior de Stamham. The

guild succeeded in obtaining an ordinance forbidding Zainer to insert

woodcuts or initials engraved on wood into his books—a prohibition

which remained in force until he came to an understanding with them, by

agreeing to use only such woodcuts and initials as should be engraved by

them. In this, or similar ways, as in every displacement of labor by

mechanical improvements, after a short struggle the cheaper and more

rapid art prevailed; the wood-engravers gave up to the printers the

principal part in the making of books, and became their servants.

The new printers were most active in the great German cities—Cologne, Mayence, Nuremberg, Ulm, Augsburg, Strasburg, and Basle—and from the presses of these cities the greatest number of books with woodcuts were issued. This is one reason why the mastering influence from this time in Northern wood-engraving was German; why German taste, German rudeness, coarseness, and crudity became the main characteristics of wood-engraving in the latter half of the fifteenth century. The Germans had been, from the first, artisans rather than artists. They had produced many anonymous prints and block-books, but they had never attained to the power and elegance of the Flemish school. Now the quality of their work became even less excellent; for decline had set in, and the increasing popularity of the new art of copperplate-engraving combined with the unfavorable influences resulting from printing, which required cheap and rapid processes, to degrade the art still lower. The illustrations in the new books had ordinarily little art-value: they were often grotesque, stiff, ignorant in design, and careless or inexpert in execution; but they had nevertheless their use and their interest.

The German influence was made more powerful, too, by other causes than the foremost part taken by Germany in printing. The Low Countries, hitherto so civilized and prosperous, the home and cradle of early Northern art, the influence of which had spread abroad and become the most powerful even over the German painters themselves, were now involved in the turbulence and disaster of the great wars of Charles the Bold. They not only lost their honorable place at the head of Northern civilization, but on the marriage of their Duchess, Mary of Burgundy, the daughter of Charles the Bold, to the Emperor Maximilian, they yielded in great part to the German influence, and became more nearly allied in character and spirit to the German cities, as they had before been more akin to France. The woodcuts in the books of the Netherlands, where printing was introduced by German workmen, share in the rudeness of German art; in proportion as their previous performance had been more excellent, the decline of the art among them seems more great. There are, occasionally, traces of the old power of design and execution in their later work; but from the time that books began to be printed Germany took the lead in wood-engraving.

The German free cities were then animated with the new spirit which was to mould the great age of Germany, and result in Dürer and Luther. The growing weakness of the Empire had fostered independence and self-reliance in the citizens, while the increase of commerce, both on the north to the German Ocean, and on the south through Venice, had introduced the wants of a higher civilization, and afforded the means to satisfy them. Local pride, which showed itself in the rivalries and public works of the cities, made their enterprise and industry more active, and gave an added impulse to the rapid transformation of military and feudal into commercial and democratic life. In these cities, where the body of men interested in knowledge and with the means of acquiring it, became every year more numerous, the new presses sent forth books of all kinds—the religious and ascetic writings of the clergy, mediæval histories, chronicles and romances, travels, voyages, botanical, military, and scientific works, and sometimes the writings of classic authors; although, in distinction from Italy, Germany was at first devoted to the reproduction of mediæval rather than Greek and Latin literature. The books in Latin, the learned tongue, were usually without woodcuts; but those in the vulgar tongues, then becoming true languages, the development and fixing of which are one of the great debts of the modern world to printing, were copiously illustrated, in order to make them attractive to the popular taste.

FIG. 8.—The Grief of Hannah. From the Cologne Bible,

1470-’75

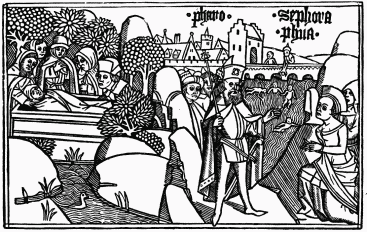

FIG. 9.—Illustration of Exodus I. From the Cologne

Bible, 1470-’75.

The great book, on which the printers exercised most care, was the Bible. Many editions were published; but the most important of these, in respect to the history of wood-engraving, was the Cologne Bible (Figs. 8, 9), which appeared before 1475, both because its one hundred and nine designs were, probably, after the block-books, the earliest series of engraved illustrations of Scripture, and were widely copied, and also because they show an extension of the sphere of thought and increased intellectual activity. The designers of these cuts relied less upon tradition, displayed more original feeling, and showed greater variety and vivacity in their treatment, than the artists who had engraved the Biblia Pauperum. The latter volume contained, as has been seen, nearly the last impression of century-old pictorial types in the mediæval conventional manner; the Cologne Bible defined conceptions of Scriptural scenes anew, and these conceptions became conventional, and re-appeared for generations in other illustrated Bibles in all parts of Europe; not, however, because of an immobility of mind characteristic of the community, as in earlier times, but partly because the printers preserved and exchanged old wood-blocks, so that the same designs from the same blocks appeared in widely distant cities, and partly because it was less costly for them to employ an inferior workman to copy the old cut, with slight variations, than to have an artist of original inventive power to design a wholly new series. Thus the Nuremberg Bible of 1482 is illustrated from the same blocks as the Cologne Bible, and the cuts in the Strasburg Bible of 1485 are poor copies of the same designs. From the marginal border which encloses the first page of the Cologne Bible it appears that wood-engraving was already looked on, not only as a means of illustrating what was said in the text, but as a means of decoration merely. Here, among the foliage and flowers, are seen running animals, and in the midst the hunter, the jongleur, the musician, the lover, the lady, and the fool—an indication of delight in nature and in the variety of human life, which, simply because it is not directly connected with the text, is the more significant of that freer range of sympathy and thought characteristic of the age. Afterward these decorative borders, often in a satiric and not infrequently in a gross vein, wholly disconnected with the text, and sometimes at strange variance with its spirit, are not uncommon. The engravings that follow this frontispiece represent the customary Scriptural scenes, and the series closes with two striking designs of the Last Judgment and of Hell. In the former angels are hurling pope, emperor, cardinal, bishop, and king into hell, and in the latter their bodies lie face to face with the souls marked with the seal of God—a satire not unexampled before this time, and indeed hardly bolder than hitherto, but of a spirit which showed that Luther was already born. “It is no small honor for our wood-engravers,” says Renouvier, “to have expressed public opinion with such hardihood, and to have shown themselves the advanced sentinels of a revolution.” The engraving in this Bible tells its own story without need of comment; but, heavy and rude as much of it is, it surpasses other German work of the same period; and it must not be forgotten that the awkwardness of the drawing was much obscured by the colors which were afterward laid on the designs by hand. It is only by accident or negligence that woodcuts were left uncolored in early German books, for the conception of a complete picture simply in black and white was a comparatively late acquisition in art, and did not guide the practice of wood-engravers until the last decade of the century, when, indeed, it effected a revolution in the art.

Of the many other illustrated Bibles which appeared during the last quarter of the fifteenth century, the one published at Augsburg, about 1475, and attributed to Gunther Zainer, alone has a peculiar interest. All but two of its seventy-three woodcuts are combined with large initial letters, occupying the width of a column, for which they serve as a background, and by which they are framed in; these are the oldest initial letters in this style, and are original in design, full of animation and vigor, and rank with the best work of the early Augsburg wood-engravers. It is not unlikely that these novel and attractive letters were the very ones of which the Augsburg guild complained in the action that they brought against Zainer in 1477. Afterward the German printers gave much attention to ornamented capitals, both in this style, which reached its most perfect examples in Holbein’s alphabets, and in the Italian mode, in which the design was relieved in white upon a black ground.

Next to the Bibles, the early chronicles and histories are of most interest for the study of wood-engraving. They are records of legendary and real events, intermingled with much extraneous matter which seemed to their authors curious or startling. They usually begin with the Creation, and come down through sacred into early legendary and secular history, recounting miracles, martyrdoms, sieges, tales of wonder and superstition, omens, anecdotes of the great princes, and the like. Each of them dwells especially upon whatever glorifies the saints, or touches the patriotism, of their respective countries. They are filled with woodcuts in illustration of their narrative, beginning with scenes from Genesis. Thus the Chronicle of Saxony, published at Mayence in 1492, contains representations of the fall of the angels, the ark of Noah, Romulus founding Rome, the arrival of the Franks and the Saxons, the deeds of Charlemagne, the overthrow of paganism, the famous emperors, Otho burning a sorcerer, Frederick Barbarossa, and the Emperor Maximilian. The Chronicle of Cologne, published in 1492, is similarly illustrated with views of the great cathedral, with representations of the Three Kings, the refusal of the five Rhine cities to pay impost, and like scenes.

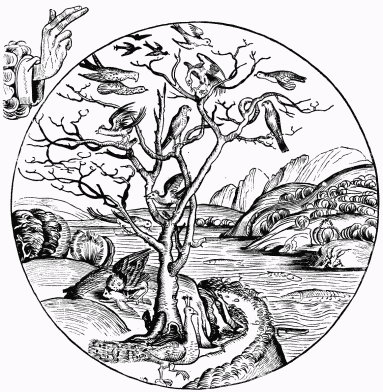

FIG. 10.—The Fifth Day of Creation. From Schedel’s

“Liber Chronicarum.” Nuremberg, 1493.

The most important of the chronicles, in respect to wood-engraving, is the Chronicle of Nuremberg (Figs. 10, 11, 12), published in that city in 1493. It contains over two thousand cuts which are attributed to William Pleydenwurff and Michael Wohlgemuth, the latter the master of Albert Dürer; they are rude and often grotesque, possessing an antiquarian rather than an artistic interest; many of them are repeated several times, a portrait serving indifferently for one prophet or another, a view of houses upon a hill representing equally well a city in Asia or in Italy, just as in many other early books—for example, in the History of the Kings of Hungary—a battle-piece does for any conflict, or a man on a throne for any king. The representations were typical rather than individual. In some of the designs there is, doubtless, a careful truthfulness, as in the view of Nuremberg, and perhaps in some of the portraits. The larger cuts show considerable vigor and boldness of conception, but none of them are so good as the illustrations, also attributed to Wohlgemuth, in the Schatzbehalter, published in the same city in 1491. The distinction of the Nuremberg chronicle does not consist in any superiority of design which can be claimed for it in comparison with other books of the same sort, but in the fact that here were printed, for the first time, woodcuts simply in black and white, which were looked on as complete without the aid of the colorist, and were in all essential points entirely similar to modern works. This change was brought about by the introduction of cross-hatching, or lines crossing each other at different intervals and different angles, but usually obliquely, by means of which blacks and grays of various intensity, or what is technically called color, were obtained. This was a process already in use in copperplate-engraving. In that art—the reverse of wood-engraving since the lines which are to give the impression on paper are incised into the metal instead of being left raised as in the wood-block—the engraver grooved out the crossing lines with the same facility and in the same way as the draughtsman draws them in a pen-and-ink sketch, the depth of color obtained depending in both cases on the relative closeness and fineness of the hatchings. In engraving in wood the task was much more difficult, and required greater nicety of skill, for, as in this case the crossing lines must be left in relief, the engraver was obliged to gouge out the minute diamond spaces between them. At first this was, probably, thought beyond the power of the workmen. The earliest woodcut in which these cross-hatchings appear is the frontispiece to Breydenbach’s Travels, published at Mayence in 1486, which is, perhaps, the finest wood-engraving of its time. In the Nuremberg chronicle this process was first extensively employed to obtain color, and thus this volume marks the beginning of that great school in wood-engraving which seeks its effects in black lines.

FIG. 11.—The Dancing Deaths. From Schedel’s “Liber

Chronicarum.” Nuremberg, 1493.

To describe the hundreds of illustrated books which the German printers published before the end of the century belongs to the bibliographer. Should any one turn to them, he would find in the cuts that they contain much diversity in character, but little in merit; he would meet at Bamberg, in the works printed by Pfister, whose Book of Fables, published 1461, is the first dated volume with woodcuts of figures, designs so rude that they are generally believed to have been hacked out by apprentices wholly destitute of training in the craft; he would notice in the books of Cologne the greater self-restraint and sense of proportion, in those of Augsburg the greater variety, vivacity, and vigor, in those of Nuremberg the greater exaggeration and grotesqueness. In the publications of some cities he would come upon the burning questions of that generation: the siege of Rhodes by the Turks, the wars of Charles the Bold against Switzerland, the martyrdom of John Huss; elsewhere he would see naïve conceptions of mediæval romance and chivalry, and not infrequently, as in the Boccaccio of Ulm, grossnesses not to be described; at Strasburg he would hardly recognize Horace and Virgil with their Teutonic features and barbaric garb; while at Mayence botanical works, which strangely mingle science, medicine, and superstition, would excite his wonder, and at Ulm military works would picture the forgotten engines of mediæval warfare; in the Netherlands, too, he would discern little difference in literature or in design; everywhere he would find the unevenness of Gothic taste—one moment creating works with a certain boldness and grandeur of conception, the next moment falling into the inane and the ludicrous; everywhere German realism making each person appear as if born in a Rhine city, and each event as if taking place within its walls; everywhere, too, an ever-widening interest in the affairs of past times and distant countries, in the thought and life of the generations that were gone, in the pursuits of the living, and the multiform problems of that age of the Reformation then coming on. It is impossible to turn from this wide survey without a recognition of the large share which wood-engraving, as the suggester and servant of printing, had in the progress made toward civilization in the North during that century. Woltmann does not over-state the fact when he says: “Wood-engraving and copperplate-engraving were not alone of use in the advance of art; they form an epoch in the entire life of mind and culture. The idea embodied and multiplied in pictures became, like that embodied in the printed word, the herald of every intellectual movement.”

FIG. 12.—Jews Sacrificing a Christian Child. From

Schedel’s “Liber Chronicarum.” Nuremberg, 1493.

As typography spread from Germany through the other countries of Europe, the art of wood-engraving accompanied it. The first books printed in the French language appeared about 1475, at Bruges, where the Dukes of Burgundy had long favored the vulgar tongue, and had collected many manuscripts written in it in their great library, then one of the finest in Europe. The first French city to issue French books from its presses was Lyons, which had learned the arts of printing and of wood-engraving from Basle, Geneva, and Nuremberg, in consequence of their close commercial relations. If a few doubtful and scattered examples of early work be excepted, it was in these Lyonese books that French wood-engraving first appeared. From the beginning of printing in France, Lyons was the chief seat of popular literature, and the centre of the industry of printing books in the vulgar tongue, as Paris was the chief seat of the literature of the learned, both in Latin and French, and devoted itself to reproducing religious and scientific works.[32] At the close of the fifteenth and beginning of the sixteenth centuries the Lyonese presses issued the largest number of first editions of the popular romances, which were sought, not merely by French purchasers, but throughout Europe. These books were meant for the middle class, who were unable to buy the costly manuscripts, illuminated with splendid miniatures, in which literature had previously been locked up. They were not considered valuable enough to be preserved with care, and have consequently become scarce; but they were published in great numbers, and exerted an influence in the spread of literary knowledge and taste which can hardly be over-estimated. Woodcuts were first inserted in them about 1476; but for twenty years after this wood-engraving was practised rather as a trade than an art, and its products have no more artistic merit than similar works in Germany. In 1493 an edition of Terence, in which the earlier rudeness gave way to some skill in design, showed the first signs of promise of the excellence which the Lyonese art was to attain in the sixteenth century.

In Paris, the German printers, who had been invited to the city by a prior of the Sorbonne, had issued Latin works for ten years before wood-engraving began to be practised. After 1483, however, Jean Du Pré, Guyot Marchand, Pierre Le Rouge, Pierre Le Caron, Antoine Verard, and other early printers applied themselves zealously to the publication of volumes of devotion, history, poetry, and romance, in which they made use of wood-engraving. The figure of the author frequently appears upon the first page, where he offers his book to the king or princess before whom he kneels; and here and there may be read sentiments like the following, which is taken from an early work of Verard’s, where they are inserted in fragmentary verses among the woodcuts: “Every good, loyal, and gallant Catholic who begins any work of imagery ought, first, to invoke in all his labor the Divine power by the blessed name of Jesus, who illumines every human heart and understanding; this is in every deed a fair beginning.”[33] The religious books, especially the Livres d’Heures (Fig. 13), were filled with the finest examples of the Parisian art, which sought to imitate the beautiful miniatures for which Paris had been famous from even before the time when Dante praised them. In consequence of this effort the woodcut in simple line served frequently only as a rough draft, to be filled in and finished by the colorist, who, indeed, sometimes wholly disregarded it and overlaid it with a new design. Before long, however, the wood-engravers succeeded in making cuts which, so far from needing color, were only injured by the addition of it; but these were considered less valuable than the illuminated designs, and the wood-engravers were hampered in the practice of their art by the miniaturists, who, like the guilds at Augsburg and other German towns, complained of the new mode of illustration as a ruinous encroachment on their craft.

Whether with or without color, the engravings in the Livres d’Heures are beautiful. Each page is enclosed in an ornamental border made up of small cuts, which are repeated in new arrangements on succeeding leaves; here and there a large cut, usually representing some Scriptural scene, is introduced in the upper portion of the page, and the text fills the vacant spaces. Not infrequently the taste displayed is Gallic rather than pious, and delights in profane legends and burlesque fancies which one would not expect to meet in a prayer-book. These volumes were so highly prized by foreign nations for the beauty of their workmanship, that they were printed in Flemish, English, and Italian. Those which were issued by Verard, Vostre, Pigouchet, and Kerver were the best products of the early French art.[34] The secular works which contain woodcuts are hardly worthy of mention, excepting Guyot Marchand’s La Danse Macabre, first published in 1485, which is a series of twenty-five spirited and graceful designs, marked by French vivacity and liveliness of fancy. In all early French work the peculiar genius of the people is not so easily distinguishable as in this example, but it is usually present, and gives a national characteristic to the art, notwithstanding the indubitable influences of the German archaic school in the earlier time, and of the Italian school in the first years of the sixteenth century.