THE ROTIFERS

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license.

Title: The Rotifers

Author: Robert Abernathy

Release Date: April 16, 2011 [EBook #35879]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ROTIFERS ***

Produced by Frank van Drogen, Greg Weeks, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net.

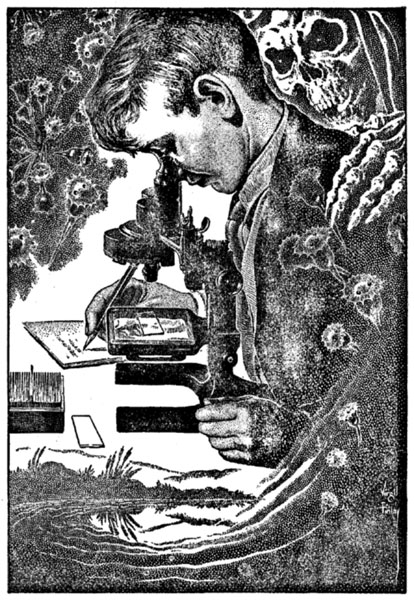

THE ROTIFERSBY Robert AbernathyBeneath the stagnant water shadowed by water lilies Harry found the fascinating world of the rotifers—but it was their world, and they resented intrusion.Illustrated by Virgil Finlay

Henry Chatham knelt by the brink of his garden pond, a glass fish bowl cupped in his thin, nervous hands. Carefully he dipped the bowl into the green-scummed water and, moving it gently, let trailing streamers of submerged water weeds drift into it. Then he picked up the old scissors he had laid on the bank, and clipped the stems of the floating plants, getting as much of them as he could in the container.

When he righted the bowl and got stiffly to his feet, it contained, he thought hopefully, a fair cross-section of fresh-water plankton. He was pleased with himself for remembering that term from the book he had studied assiduously for the last few nights in order to be able to cope with Harry's inevitable questions.

There was even a shiny black water beetle doing insane circles on the surface of the water in the fish bowl. At sight of the insect, the eyes of the twelve-year-old boy, who had been standing by in silent expectation, widened with interest.

"What's that thing, Dad?" he asked excitedly. "What's that crazy bug?"

"I don't know its scientific name, I'm afraid," said Henry Chatham. "But when I was a boy we used to call them whirligig beetles."

"He doesn't seem to think he has enough room in the bowl," said Harry thoughtfully. "Maybe we better put him back in the pond, Dad."

"I thought you might want to look at him through the microscope," the father said in some surprise.

"I think we ought to put him back," insisted Harry. Mr. Chatham held the dripping bowl obligingly. Harry's hand, a thin boy's hand with narrow sensitive fingers, hovered over the water, and when the beetle paused for a moment in its gyrations, made a dive for it.

But the whirligig beetle saw the hand coming, and, quicker than a wink, plunged under the water and scooted rapidly to the very bottom of the bowl.

Harry's young face was rueful; he wiped his wet hand on his trousers. "I guess he wants to stay," he supposed.

The two went up the garden path together and into the house, Mr. Chatham bearing the fish bowl before him like a votive offering. Harry's mother met them at the door, brandishing an old towel.

"Here," she said firmly, "you wipe that thing off before you bring it in the house. And don't drip any of that dirty pond water on my good carpet."

"It's not dirty," said Henry Chatham. "It's just full of life, plants and animals too small for the eye to see. But Harry's going to see them with his microscope." He accepted the towel and wiped the water and slime from the outside of the bowl; then, in the living-room, he set it beside an open window, where the life-giving summer sun slanted in and fell on the green plants.

The brand-new microscope stood nearby, in a good light. It was an expensive microscope, no toy for a child, and it magnified four hundred diameters. Henry Chatham had bought it because he believed that his only son showed a desire to peer into the mysteries of smallness, and so far Harry had not disappointed him; he had been ecstatic over the instrument. Together they had compared hairs from their two heads, had seen the point of a fine sewing needle made to look like the tip of a crowbar by the lowest power of the microscope, had made grains of salt look like discarded chunks of glass brick, had captured a house-fly and marvelled at its clawed hairy feet, its great red faceted eyes, and the delicate veining and fringing of its wings.

Harry was staring at the bowl of pond water in a sort of fascination. "Are there germs in the water, Dad? Mother says pond water is full of germs."

"I suppose so," answered Mr. Chatham, somewhat embarrassed. The book on microscopic fresh-water fauna had been explicit about Paramecium and Euglena, diatomes and rhizopods, but it had failed to mention anything so vulgar as germs. But he supposed that which the book called Protozoa, the one-celled animalcules, were the same as germs.

He said, "To look at things in water like this, you want to use a well-slide. It tells how to fix one in the instruction book."

He let Harry find the glass slide with a cup ground into it, and another smooth slip of glass to cover it. Then he half-showed, half-told him how to scrape gently along the bottom sides of the drifting leaves, to capture the teeming life that dwelt there in the slime. When the boy understood, his young hands were quickly more skillful than his father's; they filled the well with a few drops of water that was promisingly green and murky.

Already Harry knew how to adjust the lighting mirror under the stage of the microscope and turn the focusing screws. He did so, bent intently over the eyepiece, squinting down the polished barrel in the happy expectation of wonders.

Henry Chatham's eyes wandered to the fish bowl, where the whirligig beetle had come to the top again and was describing intricate patterns among the water plants. He looked back to his son, and saw that Harry had ceased to turn the screws and instead was just looking—looking with a rapt, delicious fixity. His hands lay loosely clenched on the table top, and he hardly seemed to breathe. Only once or twice his lips moved as if to shape an exclamation that was snatched away by some new vision.

"Have you got it, Harry?" asked his father after two or three minutes during which the boy did not move.

Harry took a last long look, then glanced up, blinking slightly.

"You look, Dad!" he exclaimed warmly. "It's—it's like a garden in the water, full of funny little people!"

Mr. Chatham, not reluctantly, bent to gaze into the eyepiece. This was new to him too, and instantly he saw the aptness of Harry's simile. There was a garden there, of weird, green, transparent stalks composed of plainly visible cells fastened end to end, with globules and bladders like fruits or seed-pods attached to them, floating among them; and in the garden the strange little people swam to and fro, or clung with odd appendages to the stalks and branches. Their bodies were transparent like the plants, and in them were pulsing hearts and other organs plainly visible. They looked a little like sea horses with pointed tails, but their heads were different, small and rounded, with big, dark, glistening eyes.

All at once Mr. Chatham realized that Harry was speaking to him, still in high excitement.

"What are they, Dad?" he begged to know.

His father straightened up and shook his head puzzledly. "I don't know, Harry," he answered slowly, casting about in his memory. He seemed to remember a microphotograph of a creature like those in the book he had studied, but the name that had gone with it eluded him. He had worked as an accountant for so many years that his memory was all for figures now.

He bent over once more to immerse his eyes and mind in the green water-garden on the slide. The little creatures swam to and fro as before, growing hazy and dwindling or swelling as they swam out of the narrow focus of the lens; he gazed at those who paused in sharp definition, and saw that, although he had at first seen no visible means of propulsion, each creature bore about its head a halo of thread-like, flickering cilia that lashed the water and drew it forward, for all the world like an airplane propeller or a rapidly turning wheel.

"I know what they are!" exclaimed Henry Chatham, turning to his son with an almost boyish excitement. "They're rotifers! That means 'wheel-bearers', and they were called that because to the first scientists who saw them it looked like they swam with wheels."

Harry had got down the book and was leafing through the pages. He looked up seriously. "Here they are," he said. "Here's a picture that looks almost like the ones in our pond water."

"Let's see," said his father. They looked at the pictures and descriptions of the Rotifera; there was a good deal of concrete information on the habits and physiology of these odd and complex little animals who live their swarming lives in the shallow, stagnant waters of the Earth. It said that they were much more highly organized than Protozoa, having a discernible heart, brain, digestive system, and nervous system, and that their reproduction was by means of two sexes like that of the higher orders. Beyond that, they were a mystery; their relationship to other life-forms remained shrouded in doubt.

"You've got something interesting there," said Henry Chatham with satisfaction. "Maybe you'll find out something about them that nobody knows yet."

He was pleased when Harry spent all the rest of that Sunday afternoon peering into the microscope, watching the rotifers, and even more pleased when the boy found a pencil and paper and tried, in an amateurish way, to draw and describe what he saw in the green water-garden.

Beyond a doubt, Henry thought, here was a hobby that had captured Harry as nothing else ever had.

Mrs. Chatham was not so pleased. When her husband laid down his evening paper and went into the kitchen for a drink of water, she cornered him and hissed at him: "I told you you had no business buying Harry a thing like that! If he keeps on at this rate, he'll wear his eyes out in no time."

Henry Chatham set down his water glass and looked straight at his wife. "Sally, Harry's eyes are young and he's using them to learn with. You've never been much worried over me, using my eyes up eight hours a day, five days a week, over a blind-alley bookkeeping job."

He left her angrily silent and went back to his paper. He would lower the paper every now and then to watch Harry, in his corner of the living-room, bowed obliviously over the microscope and the secret life of the rotifers.

Once the boy glanced up from his periodic drawing and asked, with the air of one who proposes a pondered question: "Dad, if you look through a microscope the wrong way is it a telescope?"

Mr. Chatham lowered his paper and bit his underlip. "I don't think so—no, I don't know. When you look through a microscope, it makes things seem closer—one way, that is; if you looked the other way, it would probably make them seem farther off. What did you want to know for?"

"Oh—nothing," Harry turned back to his work. As if on after-thought, he explained, "I was wondering if the rotifers could see me when I'm looking at them."

Mr. Chatham laughed, a little nervously, because the strange fancies which his son sometimes voiced upset his ordered mind. Remembering the dark glistening eyes of the rotifers he had seen, however, he could recognize whence this question had stemmed.

At dusk, Harry insisted on setting up the substage lamp which had been bought with the microscope, and by whose light he could go on looking until his bedtime, when his father helped him arrange a wick to feed the little glass-covered well in the slide so it would not dry up before morning. It was unwillingly, and only after his mother's strenuous complaints, that the boy went to bed at ten o'clock.

In the following days his interest became more and more intense. He spent long hours, almost without moving, watching the rotifers. For the little animals had become the sole object which he desired to study under the microscope, and even his father found it difficult to understand such an enthusiasm.

During the long hours at the office to which he commuted, Henry Chatham often found the vision of his son, absorbed with the invisible world that the microscope had opened to him, coming between him and the columns in the ledgers. And sometimes, too, he envisioned the dim green water-garden where the little things swam to and fro, and a strangeness filled his thoughts.

On Wednesday evening, he glanced at the fish bowl and noticed that the water beetle, the whirligig beetle, was missing. Casually, he asked his son about it.

"I had to get rid of him," said the boy with a trace of uneasiness in his manner. "I took him out and squashed him."

"Why did you have to do that?"

"He was eating the rotifers and their eggs," said Harry, with what seemed to be a touch of remembered anger at the beetle. He glanced toward his work-table, where three or four well-slides with small green pools under their glass covers now rested in addition to the one that was under the microscope.

"How did you find out he was eating them?" inquired Mr. Chatham, feeling a warmth of pride at the thought that Harry had discovered such a scientific fact for himself.

The boy hesitated oddly. "I—I looked it up in the book," he answered.

His father masked his faint disappointment. "That's fine," he said. "I guess you find out more about them all the time."

"Uh-huh," admitted Harry, turning back to his table.

There was undoubtedly something a little strange about Harry's manner; and now Mr. Chatham realized that it had been two days since Harry had asked him to "Quick, take a look!" at the newest wonder he had discovered. With this thought teasing at his mind, the father walked casually over to the table where his son sat hunched and, looking down at the litter of slides and papers—some of which were covered with figures and scribblings of which he could make nothing. He said diffidently, "How about a look?"

Harry glanced up as if startled. He was silent a moment; then he slid reluctantly from his chair and said, "All right."

Mr. Chatham sat down and bent over the microscope. Puzzled and a little hurt, he twirled the focusing vernier and peered into the eyepiece, looking down once more into the green water world of the rotifers.

There was a swarm of them under the lens, and they swam lazily to and fro, their cilia beating like miniature propellers. Their dark eyes stared, wet and glistening; they drifted in the motionless water, and clung with sucker-like pseudo-feet to the tangled plant stems.

Then, as he almost looked away, one of them detached itself from the group and swam upward, toward him, growing larger and blurring as it rose out of the focus of the microscope. The last thing that remained defined, before it became a shapeless gray blob and vanished, was the dark blotches of the great cold eyes, seeming to stare full at him—cold, motionless, but alive.

It was a curious experience. Henry Chatham drew suddenly back from the eyepiece, with an involuntary shudder that he could not explain to himself. He said haltingly, "They look interesting."

"Sure, Dad," said Harry. He moved to occupy the chair again, and his dark young head bowed once more over the microscope. His father walked back across the room and sank gratefully into his arm-chair—after all, it had been a hard day at the office. He watched Harry work the focusing screws as if trying to find something, then take his pencil and begin to write quickly and impatiently.

It was with a guilty feeling of prying that, after Harry had been sent reluctantly to bed, Henry Chatham took a tentative look at those papers which lay in apparent disorder on his son's work table. He frowned uncomprehendingly at the things that were written there; it was neither mathematics nor language, but many of the scribblings were jumbles of letters and figures. It looked like code, and he remembered that less than a year ago, Harry had been passionately interested in cryptography, and had shown what his father, at least, believed to be a considerable aptitude for such things.... But what did cryptography have to do with microscopy, or codes with—rotifers?

Nowhere did there seem to be a key, but there were occasional words and phrases jotted into the margins of some of the sheets. Mr. Chatham read these, and learned nothing. "Can't dry up, but they can," said one. "Beds of germs," said another. And in the corner of one sheet, "1—Yes. 2—No." The only thing that looked like a translation was the note: "rty34pr is the pond."

Mr. Chatham shook his head bewilderedly, replacing the sheets carefully as they had been. Why should Harry want to keep notes on his scientific hobby in code? he wondered, rationalizing even as he wondered. He went to bed still puzzling, but it did not keep him from sleeping, for he was tired.

Then, only the next evening, his wife maneuvered to get him alone with her and burst out passionately:

"Henry, I told you that microscope was going to ruin Harry's eyesight! I was watching him today when he didn't know I was watching him, and I saw him winking and blinking right while he kept on looking into the thing. I was minded to stop him then and there, but I want you to assert your authority with him and tell him he can't go on."

Henry Chatham passed one nervous hand over his own aching eyes. He asked mildly, "Are you sure it wasn't just your imagination, Sally? After all, a person blinks quite normally, you know."

"It was not my imagination!" snapped Mrs. Chatham. "I know the symptoms of eyestrain when I see them, I guess. You'll have to stop Harry using that thing so much, or else be prepared to buy him glasses."

"All right, Sally," said Mr. Chatham wearily. "I'll see if I can't persuade him to be a little more moderate."

He went slowly into the living-room. At the moment, Harry was not using the microscope; instead, he seemed to be studying one of his cryptic pages of notes. As his father entered, he looked up sharply and swiftly laid the sheet down—face down.

Perhaps it wasn't all Sally's imagination; the boy did look nervous, and there was a drawn, white look to his thin young face. His father said gently, "Harry, Mother tells me she saw you blinking, as if your eyes were tired, when you were looking into the microscope today. You know if you look too much, it can be a strain on your sight."

Harry nodded quickly, too quickly, perhaps. "Yes, Dad," he said. "I read that in the book. It says there that if you close the eye you're looking with for a little while, it rests you and your eyes don't get tired. So I was practising that this afternoon. Mother must have been watching me then, and got the wrong idea."

"Oh," said Henry Chatham. "Well, it's good that you're trying to be careful. But you've got your mother worried, and that's not so good. I wish, myself, that you wouldn't spend all your time with the microscope. Don't you ever play baseball with the fellows any more?"

"I haven't got time," said the boy, with a curious stubborn twist to his mouth. "I can't right now, Dad." He glanced toward the microscope.

"Your rotifers won't die if you leave them alone for a while. And if they do, there'll always be a new crop."

"But I'd lose track of them," said Harry strangely. "Their lives are so short—they live so awfully fast. You don't know how fast they live."

"I've seen them," answered his father. "I guess they're fast, all right." He did not know quite what to make of it all, so he settled himself in his chair with his paper.

But that night, after Harry had gone later than usual to bed, he stirred himself to take down the book that dealt with life in pond-water. There was a memory pricking at his mind; the memory of the water beetle, which Harry had killed because, he said, he was eating the rotifers and their eggs. And the boy had said he had found that fact in the book.

Mr. Chatham turned through the book; he read, with aching eyes, all that it said about rotifers. He searched for information on the beetle, and found there was a whole family of whirligig beetles. There was some material here on the characteristics and habits of the Gyrinidae, but nowhere did it mention the devouring of rotifers or their eggs among their customs.

He tried the topical index, but there was no help there.

Harry must have lied, thought his father with a whirling head. But why, why in God's name should he say he'd looked a thing up in the book when he must have found it out for himself, the hard way? There was no sense in it. He went back to the book, convinced that, sleepy as he was, he must have missed a point. The information simply wasn't there.

He got to his feet and crossed the room to Harry's work table; he switched on the light over it and stood looking down at the pages of mystic notations. There were more pages now, quite a few. But none of them seemed to mean anything. The earlier pictures of rotifers which Harry had drawn had given way entirely to mysterious figures.

Then the simple explanation occurred to him, and he switched off the light with a deep feeling of relief. Harry hadn't really known that the water beetle ate rotifers; he had just suspected it. And, with his boy's respect for fair play, he had hesitated to admit that he had executed the beetle merely on suspicion.

That didn't take the lie away, but it removed the mystery at least.

Henry Chatham slept badly that night and dreamed distorted dreams. But when the alarm clock shrilled in the gray of morning, jarring him awake, the dream in which he had been immersed skittered away to the back of his mind, out of knowing, and sat there leering at him with strange, dark, glistening eyes.

He dressed, washed the flat morning taste out of his mouth with coffee, and took his way to his train and the ten-minute ride into the city. On the way there, instead of snatching a look at the morning paper, he sat still in his seat, head bowed, trying to recapture the dream whose vanishing made him uneasy. He was superstitious about dreams in an up-to-date way, believing them not warnings from some Beyond outside himself, but from a subsconscious more knowing than the waking conscious mind.

During the morning his work went slowly, for he kept pausing, sometimes in the midst of totalling a column of figures, to grasp at some mocking half-memory of that dream. At last, elbows on his desk, staring unseeingly at the clock on the wall, in the midst of the subdued murmur of the office, his mind went back to Harry, dark head bowed motionless over the barrel of his microscope, looking, always looking into the pale green water-gardens and the unseen lives of the beings that....

All at once it came to him, the dream he had dreamed. He had been bending over the microscope, he had been looking into the unseen world, and the horror of what he had seen gripped him now and brought out the chill sweat on his body.

For he had seen his son there in the clouded water, among the twisted glassy plants, his face turned upward and eyes wide in the agonized appeal of the drowning; and bubbles rising, fading. But around him had been a swarm of the weird creatures, and they had been dragging him down, down, blurring out of focus, and their great dark eyes glistening wetly, coldly....

He was sitting rigid at his desk, his work forgotten; all at once he saw the clock and noticed with a start that it was already eleven a.m. A fear he could not define seized on him, and his hand reached spasmodically for the telephone on his desk.

But before he touched it, it began ringing.

After a moment's paralysis, he picked up the receiver. It was his wife's voice that came shrilly over the wires.

"Henry!" she cried. "Is that you?"

"Hello, Sally," he said with stiff lips. Her voice as she answered seemed to come nearer and go farther away, and he realized that his hand holding the instrument was shaking.

"Henry, you've got to come home right now. Harry's sick. He's got a high fever, and he's been asking for you."

He moistened his lips and said, "I'll be right home. I'll take a taxi."

"Hurry!" she exclaimed. "He's been saying queer things. I think he's delirious." She paused, and added, "And it's all the fault of that microscope you bought him!"

"I'll be right home," he repeated dully.

His wife was not at the door to meet him; she must be upstairs, in Harry's bedroom. He paused in the living room and glanced toward the table that bore the microscope; the black, gleaming thing still stood there, but he did not see any of the slides, and the papers were piled neatly together to one side. His eyes fell on the fish bowl; it was empty, clean and shining. He knew Harry hadn't done those things; that was Sally's neatness.

Abruptly, instead of going straight up the stairs, he moved to the table and looked down at the pile of papers. The one on top was almost blank; on it was written several times: rty34pr ... rty34pr.... His memory for figure combinations served him; he remembered what had been written on another page: "rty34pr is the pond."

That made him think of the pond, lying quiescent under its green scum and trailing plants at the end of the garden. A step on the stair jerked him around.

It was his wife, of course. She said in a voice sharp-edged with apprehension: "What are you doing down here? Harry wants you. The doctor hasn't come; I phoned him just before I called you, but he hasn't come."

He did not answer. Instead he gestured at the pile of papers, the empty fish bowl, an imperative question in his face.

"I threw that dirty water back in the pond. It's probably what he caught something from. And he was breaking himself down, humping over that thing. It's your fault, for getting it for him. Are you coming?" She glared coldly at him, turning back to the stairway.

"I'm coming," he said heavily, and followed her upstairs.

Harry lay back in his bed, a low mound under the covers. His head was propped against a single pillow, and his eyes were half-closed, the lids swollen-looking, his face hotly flushed. He was breathing slowly as if asleep.

But as his father entered the room, he opened his eyes as if with an effort, fixed them on him, said, "Dad ... I've got to tell you."

Mr. Chatham took the chair by the bedside, quietly, leaving his wife to stand. He asked, "About what, Harry?"

"About—things." The boy's eyes shifted to his mother, at the foot of his bed. "I don't want to talk to her. She thinks it's just fever. But you'll understand."

Henry Chatham lifted his gaze to meet his wife's. "Maybe you'd better go downstairs and wait for the doctor, Sally."

She looked hard at him, then turned abruptly to go out. "All right," she said in a thin voice, and closed the door softly behind her.

"Now what did you want to tell me, Harry?"

"About them ... the rotifers," the boy said. His eyes had drifted half-shut again but his voice was clear. "They did it to me ... on purpose."

"Did what?"

"I don't know.... They used one of their cultures. They've got all kinds: beds of germs, under the leaves in the water. They've been growing new kinds, that will be worse than anything that ever was before.... They live so fast, they work so fast."

Henry Chatham was silent, leaning forward beside the bed.

"It was only a little while, before I found out they knew about me. I could see them through my microscope, but they could see me too.... And they kept signaling, swimming and turning.... I won't tell you how to talk to them, because nobody ought to talk to them ever again. Because they find out more than they tell.... They know about us, now, and they hate us. They never knew before—that there was anybody but them.... So they want to kill us all."

"But why should they want to do that?" asked the father, as gently as he could. He kept telling himself, "He's delirious. It's like Sally says, he's been wearing himself out, thinking too much about—the rotifers. But the doctor will be here pretty soon, the doctor will know what to do."

"They don't like knowing that they aren't the only ones on Earth that can think. I expect people would be the same way."

"But they're such little things, Harry. They can't hurt us at all."

The boy's eyes opened wide, shadowed with terror and fever. "I told you, Dad—They're growing germs, millions and billions of them, new ones.... And they kept telling me to take them back to the pond, so they could tell all the rest, and they could all start getting ready—for war."

He remembered the shapes that swam and crept in the green water gardens, with whirling cilia and great, cold, glistening eyes. And he remembered the clean, empty fish bowl in the window downstairs.

"Don't let them, Dad," said Harry convulsively. "You've got to kill them all. The ones here and the ones in the pond. You've got to kill them good—because they don't mind being killed, and they lay lots of eggs, and their eggs can stand almost anything, even drying up. And the eggs remember what the old ones knew."

"Don't worry," said Henry Chatham quickly. He grasped his son's hand, a hot limp hand that had slipped from under the coverlet. "We'll stop them. We'll drain the pond."

"That's swell," whispered the boy, his energy fading again. "I ought to have told you before, Dad—but first I was afraid you'd laugh, and then—I was just ... afraid...."

His voice drifted away. And his father, looking down at the flushed face, saw that he seemed asleep. Well, that was better than the sick delirium—saying such strange, wild things—

Downstairs the doctor was saying harshly, "All right. All right. But let's have a look at the patient."

Henry Chatham came quietly downstairs; he greeted the doctor briefly, and did not follow him to Harry's bedroom.

When he was left alone in the room, he went to the window and stood looking down at the microscope. He could not rid his head of strangeness: A window between two worlds, our world and that of the infinitely small, a window that looks both ways.

After a time, he went through the kitchen and let himself out the back door, into the noonday sunlight.

He followed the garden path, between the weed-grown beds of vegetables, until he came to the edge of the little pond. It lay there quiet in the sunlight, green-scummed and walled with stiff rank grass, a lone dragonfly swooping and wheeling above it. The image of all the stagnant waters, the fertile breeding-places of strange life, with which it was joined in the end by the tortuous hidden channels, the oozing pores of the Earth.

And it seemed to him then that he glimpsed something, a hitherto unseen miasma, rising above the pool and darkening the sunlight ever so little. A dream, a shadow—the shadow of the alien dream of things hidden in smallness, the dark dream of the rotifers.

The dragonfly, having seized a bright-winged fly that was sporting over the pond, descended heavily through the sunlit air and came to rest on a broad lily pad. Henry Chatham was suddenly afraid. He turned and walked slowly, wearily, up the path toward the house.

END

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ROTIFERS ***

A Word from Project Gutenberg

We will update this book if we find any errors.

This book can be found under: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/35879

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation (and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules, set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to copying and distributing Project Gutenberg™ electronic works to protect the Project Gutenberg™ concept and trademark. Project Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and research. They may be modified and printed and given away – you may do practically anything with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is subject to the trademark license, especially commercial redistribution.

The Full Project Gutenberg License

Please read this before you distribute or use this work.

To protect the Project Gutenberg™ mission of promoting the free distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work (or any other work associated in any way with the phrase “Project Gutenberg”), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project Gutenberg™ License available with this file or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use & Redistributing Project Gutenberg™ electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg™ electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property (trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy all copies of Project Gutenberg™ electronic works in your possession. If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project Gutenberg™ electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. “Project Gutenberg” is a registered trademark. It may only be used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg™ electronic works even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project Gutenberg™ electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg™ electronic works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation (“the Foundation” or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project Gutenberg™ electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project Gutenberg™ mission of promoting free access to electronic works by freely sharing Project Gutenberg™ works in compliance with the terms of this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg™ name associated with the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project Gutenberg™ License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project Gutenberg™ work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate access to, the full Project Gutenberg™ License must appear prominently whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg™ work (any work on which the phrase “Project Gutenberg” appears, or with which the phrase “Project Gutenberg” is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed, copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg™ electronic work is derived from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work with the phrase “Project Gutenberg” associated with or appearing on the work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the Project Gutenberg™ trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg™ electronic work is posted with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked to the Project Gutenberg™ License for all works posted with the permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg™ License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg™.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project Gutenberg™ License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary, compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg™ work in a format other than “Plain Vanilla ASCII” or other format used in the official version posted on the official Project Gutenberg™ web site (http://www.gutenberg.org), you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon request, of the work in its original “Plain Vanilla ASCII” or other form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg™ License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying, performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg™ works unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing access to or distributing Project Gutenberg™ electronic works provided that

You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from the use of Project Gutenberg™ works calculated using the method you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg™ trademark, but he has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the address specified in Section 4, “Information about donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation.”

You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg™ License. You must require such a user to return or destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of Project Gutenberg™ works.

You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days of receipt of the work.

You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free distribution of Project Gutenberg™ works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg™ electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg™ trademark. Contact the Foundation as set forth in Section 3. below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg™ collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg™ electronic works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain “Defects,” such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES – Except for the “Right of Replacement or Refund” described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project Gutenberg™ trademark, and any other party distributing a Project Gutenberg™ electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND – If you discover a defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you ‘AS-IS,’ WITH NO OTHER WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages. If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY – You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone providing copies of Project Gutenberg™ electronic works in accordance with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production, promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg™ electronic works, harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees, that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg™ work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any Project Gutenberg™ work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg™

Project Gutenberg™ is synonymous with the free distribution of electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the assistance they need, is critical to reaching Project Gutenberg™'s goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg™ collection will remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure and permanent future for Project Gutenberg™ and future generations. To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4 and the Foundation web page at http://www.pglaf.org .

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit 501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at http://www.gutenberg.org/fundraising/pglaf . Contributions to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S. Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at 809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official page at http://www.pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg™ depends upon and cannot survive without wide spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations ($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any particular state visit http://www.gutenberg.org/fundraising/donate

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations. To donate, please visit: http://www.gutenberg.org/fundraising/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg™ electronic works.

Professor Michael S. Hart is the originator of the Project Gutenberg™ concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project Gutenberg™ eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg™ eBooks are often created from several printed editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S. unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Each eBook is in a subdirectory of the same number as the eBook's eBook number, often in several formats including plain vanilla ASCII, compressed (zipped), HTML and others.

Corrected editions of our eBooks replace the old file and take over the old filename and etext number. The replaced older file is renamed. Versions based on separate sources are treated as new eBooks receiving new filenames and etext numbers.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg™, including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.