The Project Gutenberg EBook of Mr. Punch in Bohemia, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Mr. Punch in Bohemia Author: Various Editor: J. A. Hammerton Illustrator: Various Release Date: April 14, 2011 [EBook #35874] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MR. PUNCH IN BOHEMIA *** Produced by Neville Allen, David Edwards and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Designed to provide in a series of volumes, each complete in itself, the cream of our national humour, contributed by the masters of comic draughtsmanship and the leading wits of the age to "Punch," from its beginning in 1841 to the present day.

Time was when Bohemianism was synonymous with soiled linen and unkempt locks. But those days of the ragged Bohemia have happily passed away, and that land of unconventional life—which had finally grown conventional in its characteristics—has now become "a sphere of influence" of Modern Society! In a word, it is now respectable. There are those who firmly believe it has been wiped off the social map. The dress suit and the proprieties are thought by some to be incompatible with its existence. But it is not so; the new Bohemia is surely no less delightful than the old. The way to it is through the doors of almost any of the well-known literary and art clubs of London. Its inhabitants are our artists, our men of letters, our musicians, and, above all, our actors.

In the present volume we are under the guidance of Mr. Punch, himself the very flower of London's Bohemia, into this land of light-hearted laughter and the free-and-easy[Pg 6] manner of living. We shall follow him chiefly through the haunts of the knights of the pen and pencil, as we have another engagement to spend some agreeable hours with him in the theatrical and musical world. It should be noted, however, that we shall not be limited to what has been called "Upper Bohemia", but that we shall, thanks to his vast experience, be able to peep both at the old and new.

Easily first amongst the artists who have depicted the humours of Bohemia is Phil May. Keene and Du Maurier run him close, but their Bohemia is on the whole more artistic, less breezily, raggedly, hungrily unconventional than his. It is a subject that has inspired him with some of his best jokes, and some of his finest drawings.

The Invalid Author.—Wife. "Why, nurse is reading a book, darling! Who gave it her?" Husband. "I did, my dear." Wife. "What book is it?" Husband. "It's my last." Wife. "Darling! When you knew how important it is that she shouldn't go to sleep!"

"All right, sir. I'll just wash 'er face, sir, and then she shall come round to your stoodio, sir."

Most sticks have two ends, and a muff gets hold of the wrong one.

The good boy studies his lesson; the bad boy gets it.

If sixpence were sunshine, it would never be lost in the giving.

The man that is happy in all things will rejoice in potatoes.

Three removes are better than a dessert.

Dinner deferred maketh the hungry man mad.

Bacon without liver is food for the mind.

Forty winks or five million is one sleep.

You don't go to the Mansion House for skilligolee.

Three may keep counsel if they retain a barrister.

What is done cannot be underdone.

You can't make a pair of shoes out of a pig's tail.

Dinner hour is worth every other, except bedtime.

No hairdresser puts grease into a wise man's head.[Pg 12]

An upright judge for a downright rogue.

Happiness is the hindmost horse in the Derby.

Look before you sit.

Bear and forebear is Bruin and tripe.

Believe twice as much as you hear of a lady's age.

Content is the conjuror that turns mock-turtle into real.

There is no one who perseveres in well-doing like a thorough humbug.

The loosest fish that drinks is tight.

Education won't polish boots.

Experience is the mother of gumption.

Half-a-crown is better than no bribe.

Utopia hath no law.

There is no cruelty in whipping cream.

Care will kill a cat; carelessness a Christian.

He who lights his candle at both ends, spills grease.

Keep your jokes to yourself, and repeat other people's.

What our Artist has to put up with.—Fond Mother. "I do wish you would look over some of my little boy's sketches, and give me your candid opinion on them. They strike me as perfectly marvellous for one so young. The other day he drew a horse and cart, and, I can assure you, you could scarcely tell the difference."

["Editors, behind their officialism, are human just like other folks, for they think and they work, they laugh and they play, they marry—just as others do. The best of them are brimful of human nature, sympathetic and kindly, and full of the zest of life and its merry ways."—Round About.]

To look at, the ordinary editor is so like a human being that it takes an expert to tell the difference.

When quite young they make excellent pets, but for some strange reason people never confess that they have editors in the house.

Marriage is not uncommon among editors, and monogamy is the rule rather than the exception.

The chief hobby of an editor is the collection of stamped addressed envelopes, which are sent to him in large numbers. No one knows why he should want so many of these, but we believe he is under the impression that by collecting a million of them he will be able to get a child into some hospital.

Of course in these enlightened days it is illegal to shoot editors, while to destroy their young is tantamount to murder.

Country Cousin (looking at Index of R. A. Catalogue). "Uncle, what does 1, 3, 6, 8, after a man's name, mean?"

Uncle (who has been dragged there much against his will). "Eh! What? 1, 3——Oh, Telephone number!"

In the Artist's Room.—Potztausend. "My friend, it is kolossal! most remark-worthy! You remind me on Rubinstein; but you are better as he." Pianist (pleased). "Indeed! How?" Potztausend. "In de bersbiration. My friend Rubinstein could never bersbire so moch!"

Brothers in Art.—New Arrival. "What should I charge for teaching ze pianoforte?" Old Stager. "Oh, I don't know." N. A. "Vell, tell me vot you charge." O. S. "I charge five guineas a lesson." N. A. "Himmel! how many pupils have you got?" O. S. "Oh, I have no pupils!"

["Journalism.—Gentleman (barrister) offers furnished bedroom in comfortable, cheerful chambers in Temple in return for equivalent journalistic assistance, &c."—Times.]

The "equivalent" is rather a nice point. Mr. Punch suggests for other gentlemen barristers the following table of equivalence:—

| 1 furnished bedroom. | = | 1 introduction (by letter) to sub-editor of daily paper. |

| 1 furnished bedroom with use of bath. | = | 1 introduction (personal) to sub-editor. |

| 1 bed-sitting-room. | = | 1 introduction and interview (five minutes guaranteed) with editor. |

| 2 furnished rooms. | = | 1 lunch (cold) with Dr. Robertson Nicoll. |

| 2 furnished rooms, with use of bath. | = | 1 lunch (hot) with Dr. Nicoll and Claudius Clear. |

| 1 furnished flat, with all modern conveniences, electric light, trams to the corner, &c. | = | 1 bridge night with Lord Northcliffe, Sir George Newnes, and Mr. C. A. Pearson. |

Little Griggs (to caricaturist). "By Jove, old feller, I wish you'd been with me this morning; you'd have seen such a funny looking chap!"

(Model wishing to say something pleasant.) "You must have painted uncommonly well when you were young!"

Dinner and Dress.—Full dress is not incompatible with low dress. At dinner it is not generally the roast or the boiled that are not dressed enough. If young men are raw, that does not much signify but it is not nice to see girls underdone.

A Professional View of Things.—Trecalfe, our bookseller, who has recently got married, says of his wife, that he feels that her life is bound up in his.

| 2 sips | make | 1 glass. |

| 2 glasses | make | 1 pint. |

| 2 pints | makes | 1 quart bottle. |

| 1 bottle | makes | one ill. |

Mrs. Mashem. "Bull-bull and I have been sitting for our photographs as 'Beauty and the Beast'!"

Lord Loreus (a bit of a fancier). "Yes; he certainly is a beauty, isn't he?"]

Short Rules for Calculation.—To Find the Value of a Dozen Articles.—Send them to a magazine, and double the sum offered by the proprietor.

Another Way.—Send them to the butterman, who will not only fix their value, but their weight, at per pound.

To Find the Value of a Pound at any price.—Try to borrow one, when you are desperately hard up.

Member of the Lyceum Club. Have you read Tolstoi's "Resurrection"?

Member of the Cavalry Club. No. Is that the name of Marie Corelli's new book?

First Reveller (on the following morning). "I say, is it true you were the only sober man last night?"

Second Reveller. "Of course not!"

First Reveller. "Who was, then?"

Brown (who, with his friends Jones and Robinson, is in town for a week and is "going it"). "Now, Mr. Costumier, we are going to this 'ere ball, and we want you to make us hup as the Three Musketeers!"

A Cheerful Prospect.—Jones. "I say, Miss Golightly, it's awfully good of you to accompany me, you know. If I've tried this song once, I've tried it a dozen times—and I've always broken down in the third verse!"

Beyond Praise.—Roscius. "But you haven't got a word of praise for anyone. I should like to know who you would consider a finished artist?"

Criticus. "A dead one, my boy—a dead one!"

Stale News Freshly Told.—A physician cannot obtain recovery of his fees, although he may cause the recovery of his patient.

Dress may be seized for rent, and a coat without cuffs may be collared by the broker.

A married woman can acquire nothing, the proper tie of marriage making all she has the proper-ty of her husband.

You may purchase any stamp at the stamp-office, except the stamp of a gentleman.

Pawnbrokers take such enormous interest in their little pledges, that if they were really pledges of affection, the interest taken could hardly be exceeded.

The Authors of our own Pleasures.—Next to the pleasure of having done a good action, there is nothing so sweet as the pleasure of having written a good article!

Change for the Better.—When the organ nuisance shall have been swept away from our streets, that fearful instrument of ear-piercing torture called the hurdy-gurdy will then (thank Parliament!) be known as the un-heardy-gurdy.

1. Never put off till to-morrow what you can do to-day.

2. Never trouble another for a trifle which you can do yourself.

3. Never spend your money before you have it, if you would make the most of your means.

4. Nothing is troublesome that we do willingly.

1. Put off till to-morrow the dun who won't be done to-day.

2. When another would trouble you for a trifle, never trouble yourself.

3. Spend your money before you have it; and when you have it, spend it again, for by so doing you enjoy your means twice, instead of only once.

4. You have only to do a creditor willingly, and he will never be troublesome.

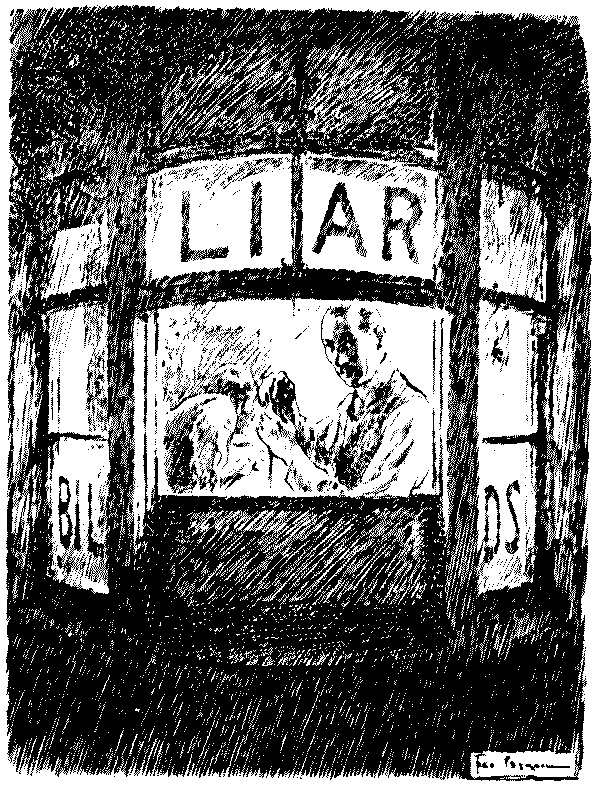

The True Test.— First Screever (stopping before a pastel in a picture dealer's window). "Ullo 'Erbert, look 'ere! Chalks!"

Second Screever. "Ah, very tricky, I dessay. But you set that chap on the pivement alongside o' you an' me, to dror 'arf a salmon an' a nempty 'at, an' where 'ud 'e be?"

First Screever. "Ah!"

[Exeunt ambo.

Musical News (Noose).—We perceive from a foreign paper that a criminal who has been imprisoned for a considerable period at Presburg has acquired a complete mastery over the violin. It has been announced that he will shortly make an appearance in public. Doubtless, his performance will be a solo on one string.

Sporting Prophet (playing billiards). Marker, here's the tip off this cue as usual.

Marker. Yes, sir. Better give us one of your "tips," sir, as they never come off.

Art Dogma.—An artist's wife never admires her husband's work so much as when he is drawing her a cheque.

The United Effort of Six Royal Academicians.—What colour is it that contains several? An umber (a number).

Mem. at Burlington House.—A picture may be "capitally executed" without of necessity being "well hung." And vice versâ.

She. "I didn't know you were a musician, Herr Müller."

He. "A musician? Ach, no—Gott vorpit! I am a Wagnerian!"

(Wrung from him by the repeated calls of the printer's boy)

"Oh! that devils' visits were, like angels', 'few and far between!'"

Q. What is the difference between a surgeon and a wizard?

A. The one is a cupper and the other is a sorcerer.

Q. Why is America like the act of reflection?

A. Because it is a roomy-nation.

Q. Why is your pretty cousin like an alabaster vase?

A. Because she is an objet de looks.

Q. How is it that a man born in Truro can never be an Irishman?

A. Because he always is a true-Roman.

Q. Why is my game cock like a bishop?

A. Because he has his crows here (crozier).

Philistine art may stand all critic shocks

Whilst it gives private views—of pretty frocks!

Comic Man (to unappreciated tenor, whose song has just been received in stony silence). "I say, you're not going to sing an encore, are you?"

Unappreciated Tenor (firmly). "Yes, I am. Serve them right!"

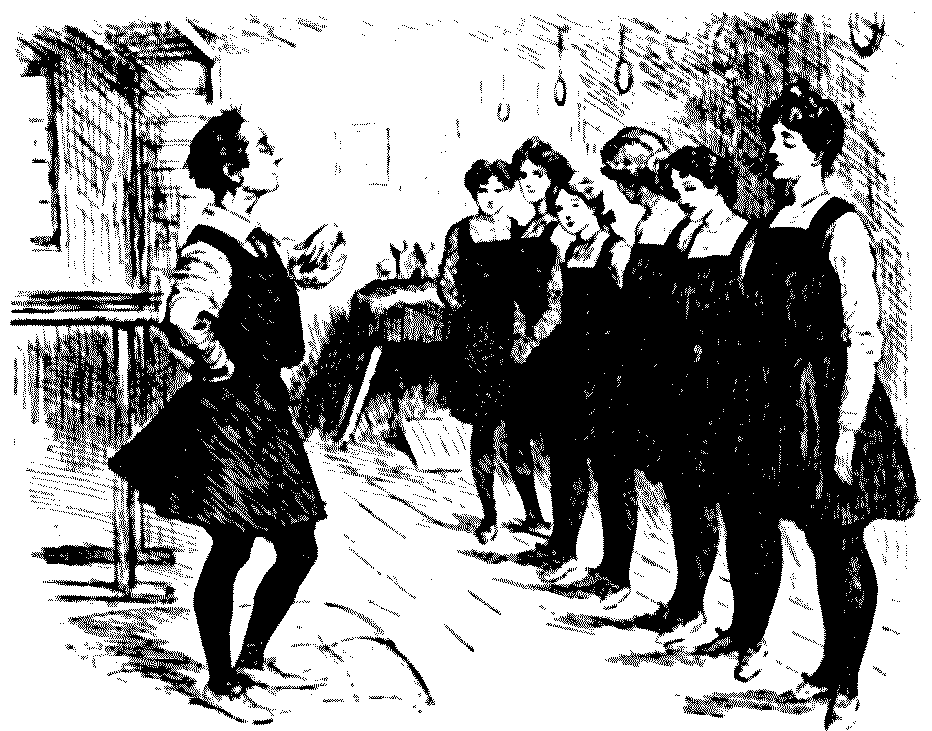

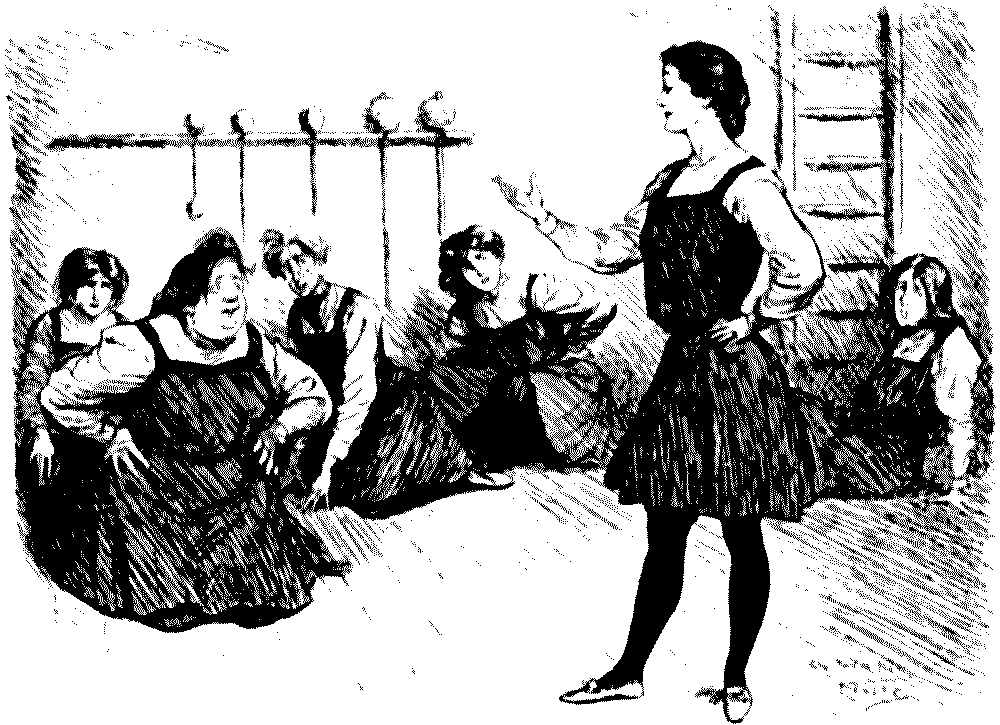

Swedish Exercise Instructress. "Now, ladies, if you will only follow my directions carefully, it is quite possible that you may become even as I am!"

Instructress (to exhausted class, who have been hopping round room for some time). "Come! Come! That won't do at all. You must look cheerful. Keep smiling—smiling all the time!"

The proof of a pudding is in the eating:

The proof of a woman is in making a pudding;

And the proof of a man is in being able to dine without one.

A Reflection on Literature.—It is a well-authenticated fact, that the name of a book has a great deal to do with its sale and its success. How strange that titles should go for so much in the republic of letters.

Motto for the Rejected at the Royal Academy (suggested by one of the Forty).—"Hanging's too good for them!"

Suggestion for a Music-Hall Song (to suit any Lionne Comique).—"Wink at me only with one eye," &c., &c.

Ample Grounds for Complaint.—Finding the grounds of your coffee to consist of nothing but chicory.

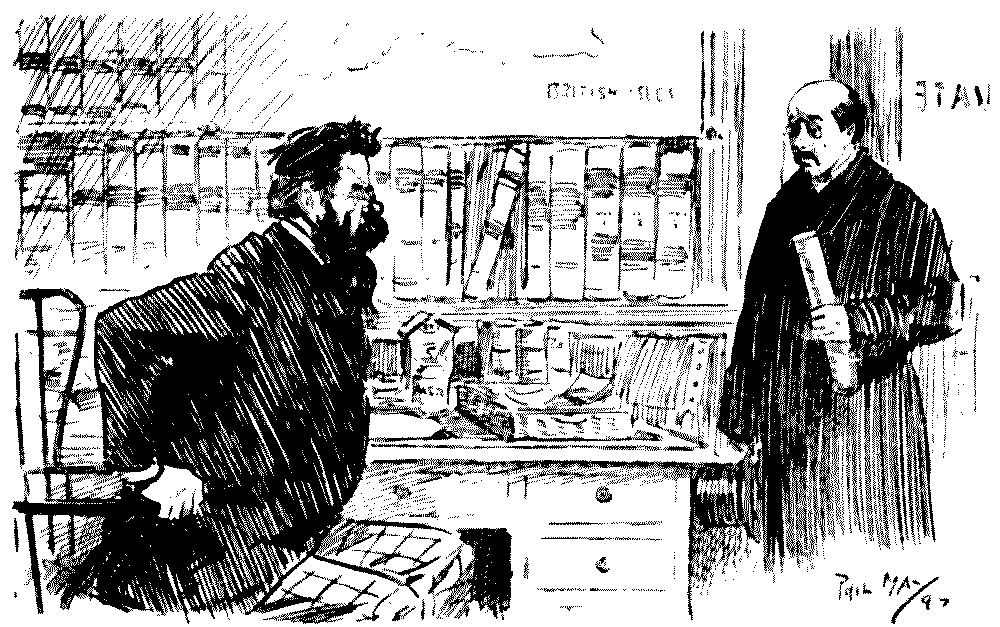

Publisher (impatiently). "Well, sir, what is it?"

Poet (timidly). "O—er—are you Mr. Jobson?"

Publisher (irritably). "Yes."

Poet (more timidly). "Mr. George Jobson?"

Publisher (excitably). "Yes, sir, that's my name."

Poet (more timidly still). "Of the firm of Messrs. Jobson and Doodle?"

Publisher (angrily). "Yes. What do you want?"

Poet "Oh—I want to see Mr. Doodle!"

The Rector. "Oh, piano, Mr. Brown! Pi-an-o!"

Mr. Brown. "Piano be blowed! I've come here to enjoy myself!"

Customer.—"Have you 'How to be happy though married'?"

Bookseller. "No, sir. We have run out at present of the work you mention; but we are selling this little book by the hundred."

Since, my dear Jones, you are good enough to ask for my advice, need I say that your success in business will depend chiefly upon judicious advertisement? You are bringing out, I understand, a thrilling story of domestic life, entitled "Maria's Marriage." Already, I am glad to learn, you have caused a paragraph to appear in the literary journals contradicting "the widespread report that Mr. Kipling and the German Emperor have collaborated in the production of this novel, the appearance of which is awaited with such extraordinary interest." And you have induced a number of papers to give prominence to the fact that Mr. Penwiper dines daily off curry and clotted cream. So far, so good. Your next step will be to send out review-copies, together with ready-made laudatory criticisms; in order, as you will explain, to save the hard worked reviewers trouble. But, you will say, supposing this ingenious device to[Pg 44] fail? Supposing "Maria's Marriage" to be universally "slated"? Well, even then you need not despair. With a little practice, you will learn the art of manufacturing an attractive advertisement column from the most unpromising material. Let me give you a brief example of the method:—

"Mr. Penwiper's latest production, 'Maria's Marriage,' scarcely calls for serious notice. It seems hard to believe that even the most tolerant reader will contrive to study with attention a work of which every page contains glaring errors of taste. Humour, smartness, and interest are all conspicuously wanting."—The Thunderer.

"This book is undeniably third-rate—dull, badly-written, incoherent; in fine, a dismal failure."—The Wigwam.

"If 'Maria's Marriage' has any real merit, it is as an object-lesson to aspiring authors. Here, we would say to them, is a striking example of the way in which romance should not be written. Set yourself to produce a work exactly its opposite in every particular, and the chances are that you[Pg 46] will produce, if not a masterpiece, at least, a tale free from the most glaring faults. For the terrible warning thus afforded by his volume to budding writers, Mr. Penwiper deserves to be heartily thanked."—Daily Telephone.

"'Maria's Marriage' is another book that we have received in the course of the month."—The Parachute.

"Maria's Marriage!" "Maria's Marriage!"

Gigantic Success—The Talk of London.

The 29th edition will be issued this week if the sale of twenty-eight previous ones makes this necessary. Each edition is strictly limited!

"Maria's Marriage!"

The voice of the Press is simply unanimous. Read the following extracts—taken almost at random from the reviews of leading papers.

"Mr. Penwiper's latest production ... calls for serious notice ... the reader will ... study with attention a work of which every page contains taste, humour, smartness and interest!"—The Thunderer.[Pg 48]

"Undeniably ... fine!"—The Wigwam.

"Has ... real merit ... an object lesson ... a striking example of the way in which romance ... should be written. A masterpiece ... free from faults. Mr. Penwiper deserves to be heartily thanked."—Daily Telephone.

"The book ... of the month!"—The Parachute, &c., &c.

"Maria's Marriage!" A veritable triumph! Order it from your bookseller to-day!

That, my dear Jones, is how the trick is done. I hope to give you some further hints on a future occasion.

"Operator" (desperately, after half an hour's fruitless endeavour to make a successful "picture" from unpromising sitter). "Suppose, madam, we try a pose with just the least suggestion of—er—sauciness?"

(Time 3 p.m.).—Hospitable Host. "Have c'gar, old f'lla?"

Languid Visitor. "No—thanks."

H. H. "Cigarette then?"

His Visitor. "No—thanks. Nevar smoke 'mejately after breakfast."

H. H. "Can't refuse a toothpick, then, old f'lla?"

Buyer. "In future, as my collection increases, and my wall-space is limited, and price no object, perhaps you would let me have a little more 'picture,' and a little less 'mount'!"

Jones (to his fair partner, after their opponents have declared "clubs"). "Shall I play to 'clubs', partner?"

Fair Partner (who has never played bridge before). "Oh, no, please don't, Mr. Jones. I've only got two little ones."

She. "And are all these lovely things about which you write imaginary?"

The Poet. "Oh, no, Miss Ethel. I have only to open my eyes and I see something beautiful before me."

She. "Oh, how I wish I could say the same!"

[At The R.A.—First Painter. "I've just been showing my aunt round. Most amusing. Invariably picks out the wrong pictures to admire and denounces the good ones!"

Second Painter. "Did she say anything about mine?"

First Painter. "Oh, she liked yours!"

"I say, old man, I've invented a new drink. Big success! Come and try it."

"What's it made of?"

"Well, it's something like the ordinary whisky and soda, but you put more whisky in it!"

Sylvia. "I wonder whether he'll be a soldier or a sailor?"

Mamma. "Wouldn't you like him to be an artist, like papa?"

Sylvia. "Oh, one in the family's quite enough!"

A well-known diner-out has, we learn, collected his reminiscences, and would be glad to hear from some obliging gentleman or gentlemen who would "earnestly request" him to publish them.

We should add that no names would be mentioned, the preface merely opening as follows:—-

"Although these stray gleanings of past years are of but ephemeral value, and though they were collected with no thought of publication, the writer at the earnest request of a friend" (or "many friends," if more than one) "has reluctantly consented to give his scattered reminiscences to the world."

The following volumes in "The Biter Bit" series are announced as shortly to appear:—

"The Fighter Fit; or practical hints on pugilistic training."

"The Lighter Lit: a treatise on the illumination of Thames barges."

"The Slighter Slit: or a new and economical method of cutting out."

"The Tighter Tit: studies in the comparative inebriation of birds."

| Some fine form was exhibited | A two-figure break |

| A heat of 500 up | Finishing the game with a cannon |

| Opening with the customary miss | Spot barred |

"But it is impossible for you to see the President. What do you want to see him for?"

"I want to show him exactly where I want my picture hung."

Infuriated Outsider. "R-r-r-rejected, sir!—Fwanospace, sir!" (With withering emphasis.) "'Want—of—space—sir!!"

"Look here, Schlumpenhagen, you must help us at our smoking concert. You play the flute, don't you?"

"Not ven dere ish anypotty apout."

"How's that?"

"Dey von't let me!"

There is no sympathy in England so universally felt, so largely expressed, as for a person who is likely to catch cold.

When a person loses his reputation, the very last place where he goes to look for it is the place where he has lost it.

No gift so fatal as that of singing. The principal question asked, upon insuring a man's life, should be, "Do you sing a good song?"

Many of us are led by our vices, but a great many more of us follow them without any leading at all.

To show how deceptive are appearances, more gentlemen are mistaken for waiters, than waiters for gentlemen.

To a retired tradesman there can be no greater convenience than that of having a "short sight." In truth, wealth rarely improves the vision. Poverty, on the contrary, strengthens it. A man, when he is poor, is able to discover objects at the[Pg 64] greatest distance with the naked eye, which he could not see, though standing close to his elbow, when he was rich.

If you wish to set a room full of silent people off talking, get some one to sing a song.

The bore is happy enough in boring others, but is never so miserable as when left alone, when there is no one but himself to bore.

The contradictions of this life are wonderful. Many a man, who hasn't the courage to say "no," never misses taking a shower-bath every morning of his life.

Enter Smith, F.R.S., meeting Brown, Q.C.

Smith. Raw day, eh?

Brown. Very raw. Glad when it's done.

[Exit Brown, Q.C. Exit Smith, F.R.S., into smoking-room, where he tells a good thing that Brown said.

Miss Jones. "How came you to think of the subject, Mr. de Brush?"

Eccentric Artist. "Oh, I have had it in my head for years!"

Miss Jones. "How wonderful! What did the papers say?"

Eccentric Artist. "Said it was full of 'atmosphere,' and suggested 'space.'"]

Artist (who thinks he has found a good model for his Touchstone). "Have you any sense of humour, Mr. Bingles?"

Model. "Thank y' sir, no, sir, thank y'. I enj'ys pretty good 'ealth, sir, thank y' sir!"

Miss Fillip (to gentleman whose name she did not catch when introduced). Have you read A Modern Heliogabolus?

He. Yes, I have.

Miss F. All through?

He. Yes, from beginning to end.

Miss F. Dear me! I wonder you're alive! How did you manage to get through it?

He (diffidently). Unfortunately, I wrote it.

[Miss F. catches a distant friend's eye.

(Artistic-minded Youth in midst of a fierce harangue from his father, who is growing hotter and redder). "By Jove, that's a fine bit of colour, if you like!"

Art-Master (who has sent for a cab, pointing to horse). "What do you call that?"

Cabby. "An 'orse, sir."

Art-Master. "A horse! Rub it out, and do it again!"

Take time by the forelock—to have his hair cut.

Follow your leader—in your daily paper.

The proof of the pudding is in the eating—a great deal of it.

Never look a gift-horse in the mouth—lest you should find false teeth.

The hare with many friends—was eaten at last.

A stitch in time saves nine—or more naughty words, when a button comes off while you are dressing in a great hurry for dinner.

One man's meat is another man's poison—when badly cooked.

Don't count your chickens before they are hatched—by the patent incubator.

Love is blind—and unwilling to submit to an operation.

First catch your hare—then cook it with rich gravy.

Nil Desperandum—Percy Vere.

Scene: Fashionable Auction Rooms. A Picture Sale.—

Amateur Collector (after taking advice of Expert No. 1, addresses Expert No. 2). "What do you think of the picture? I am advised to buy it. Is it not a fine Titian?"

Expert No. 2 (wishing to please both parties). "I don't think you can go far wrong, for anyhow, if it isn't a Titian it's a repe-tition."

If the cap fits, wear it—out.

Six of one, and half-a-dozen of the other—make exactly twelve.

None so deaf as those who won't hear—hear! hear!

Faint heart never won fair lady—nor dark one either.

Civility costs nothing—nay, is something to your credit.

The best of friends must part—their hair.

Any port in a storm—but old port preferred.

One good turn deserves another—in waltzing.

Youth at the prow and pleasure at the helm—very sea-sick.

Amateur "Minimus Poet" (who has called at the office twice a week for three months). "Could you use a little poem of mine?"

Editor (ruthlessly determined that this shall be his final visit). "Oh, I think so. There are two or three broken panes of glass, and a hole in the skylight. How large is it?"

To find the value of a Cook.—Divide the services rendered by the wages paid; deduct the kitchen stuff, subtract the cold meat by finding how often three policemen will go into one area, and the quotient will help you to the result.

To find the value of a Friend.—Ask him to put his name to a bill.

To find the value of Time.—Travel by a Bayswater omnibus.

To find the value of Eau de Cologne.—Walk into Smithfield market.

To find the value of Patience.—Consult Bradshaw's Guide to ascertain the time of starting of a railway train.

Note by a Social Cynic.—They may abolish the "push" stroke at billiards, but they'll never do so in society.

From our own Irrepressible One (still dodging custody).—Q. Why is a daily paper like a lamb? A. Because it is always folded.

Hostess (to new Curate). "We seem to be talking of nothing but horses, Mr. Soothern. Are you much of a sportsman?"

Curate. "Really, Lady Betty, I don't think I ought to say that I am. I used to collect butterflies; but I have to give up even that now!"

"The gods confound thee! Dost thou hold there still?"

Antony and Cleopatra, Act II., Sc. 5.

Proprietor of Travelling Menagerie. "Are you used to looking after horses and other animals?"

Applicant for Job. "Yessir. Been used to 'orses all my life."

P. O. T. M. "What steps would you take if a lion got loose?"

A. F. J. "Good long 'uns, mister!"

May be Heard Everywhere.—"Songs without words"—a remarkable performance; but perhaps a still more wonderful feat is playing upon words.

(Adapted to various Sorts and Conditions of Men)

Lawyer. Tax my bill.

Doctor. Dash my draughts.

Soldier. Snap my stock.

Parson. Starch my surplice.

Bricklayer. I'll be plastered.

Bricklayer's Labourer. Chop my hod.

Carpenter. Saw me.

Plumber and Glazier. Solder my pipes. Smash my panes.

Painter. I'm daubed.

Brewer. I'm mashed.

Engineer. Burst my boiler.

Stoker. Souse my coke.

Costermonger. Rot my taturs.

Dramatic Author. Steal my French Dictionary.

Actor. I'll be hissed.

Tailor. Cut me out. Cook my goose.

Linendraper. Soil my silks. Sell me off.[Pg 80]

Grocer. Squash my figs. Sand my sugar. Seize my scales.

Baker. Knead my dough. Scorch my muffins.

Auctioneer. Knock me down.

"The Players are Come!"—First Player (who has had a run of ill-luck). I'm regularly haunted by the recollection of my losses at baccarat.

Second Player. Quite Shakespearian! "Banco's ghost."

Something to Live For.—(From the Literary Club Smoking-room.) Cynicus. I'm waiting till my friends are dead, in order to write my reminiscences?

Amicus. Ah, but remember. "De mortuis nil nisi bonum."

Cynicus. Quite so. I shall tell nothing but exceedingly good stories about them.

A Contradiction.—In picture exhibitions, the observant spectator is struck by the fact that works hung on the line are too often below the mark.

Fair Amateur (to carpenter). "My picture is quite hidden with that horrid ticket on it. Can't you fix it on the frame?" Carpenter. "Why, you'll spoil the frame, mum!"

Jones. "Do you drink between meals?"

Smith. "No. I eat between drinks."

Jones. "Which did you do last?"

Smith. "Drink."

Jones. "Then we'd better go and have a sandwich at once!"

The Quick Grub Street Co. beg to announce that they have opened an Establishment for the Supply of Literature in all its Branches.

Every Editor should send for our Prices and compare them with those of other houses.

We employ experienced poets for the supply of garden verses, war songs, &c., and undertake to fill any order within twenty-four hours of its reaching us. Our Mr. Rhymeesi will be glad to wait upon parties requiring verse of any description, and, if the matter is at all urgent, to execute the order on the spot.

Actor-managers before going elsewhere should give us a call. Our plays draw wherever they are presented, even if it is only bricks.

Testimonial.—A manager writes: "The play you kindly supplied, The Blue Bloodhound of Bletchley,[Pg 88] is universally admitted to be unlike anything ever before produced on the stage."

Musical comedies (guaranteed absolutely free from plot) supplied on shortest notice.

For society dialogues we use the very best duchesses; while a first-class earl's daughter is retained for Court and gala opera.

For our new line of vie intime we employ none but valets and confidential maids, who have to serve an apprenticeship with P.A.P.

is always up-to-date, and our Mr. Stickit will be pleased to call on any editor on receipt of post-card.

N.B.—We guarantee our Scotch Idyll to be absolutely unintelligible to any English reader, and undertake to refund money if it can be proved that such is not the case.

Our speciality, however, is our Six-Shilling Shocker, as sold for serial purposes. Editors with papers that won't "go" should ask for one of these. When ordering please state general idea required[Pg 90] under one of our recognised sections, as foreign office, police, mounted infantry, cowardice, Rome, &c., &c.

Any gentleman wishing to have a biography of himself produced in anticipation of his decease should communicate with us.

The work would, of course, be published with a note to the effect that the writing had been a labour of love; that moreover the subject with his usual modesty had been averse from the idea of a biography.

Testimonial.—Sir Sunny Jameson writes: "The Life gives great satisfaction. No reference made, however, to my munificent gift of £50 to the Referees' Hospital. This should be remedied in the next edition. The work, however, has been excellently done. You have made me out to be better than even I ever thought myself."

For love letters,

For the Elizabethan vogue,

For every description of garden meditations,

Give the Quick Grub Street Company a trial.

Papa (literary, who has given orders he is not to be disturbed). "Who is it?"

Little Daughter. "Scarcely anybody, dear papa!"

The Fair Authoress of "Passionate Pauline," gazing fondly at her own reflection, writes as follows:—

"I look into the glass, reader. What do I see?

"I see a pair of laughing, espiègle, forget-me-not blue eyes, saucy and defiant; a mutine little rose-bud of a mouth, with its ever-mocking moue; a tiny shell-like ear, trying to play hide-and-seek in a tangled maze of rebellious russet gold; while, from underneath the satin folds of a rose-thé dressing-gown, a dainty foot peeps coyly forth in its exquisitely-pointed gold morocco slipper," &c., &c.

(Vide "Passionate Pauline", by Parbleu.)

First Gourmet. "That was Mr. Dobbs I just nodded to."

Second Gourmet. "I know."

First G. "He asked me to dine at his house next Thursday—but I can't. Ever dined at Dobbs's?"

Second G. "No. Never dined. But I've been there to dinner!"

Auctioneer. "Lot 52. A genuine Turner. Painted during the artist's lifetime. What offers, gentlemen?"

Millionaire (who has been shown into fashionable artist's studio, and has been kept waiting a few minutes). "Shop!"

WHAT'S in the pot mustn't be told to the pan.

There's a mouth for every muffin.

A clear soup and no flavour.

As drunk as a daisy.

All rind and no cheese.

Set a beggar on horseback, and he will cheat the livery-stable keeper.

There's a B in every bonnet.

Two-and-six of one and half-a-crown of the other.

The insurance officer dreads a fire.

First catch your heir, then hook him.

Every plum has its pudding.

Short pipes make long smokes.

It's a long lane that has no blackberries.

Wind and weather come together.

A flower in the button-hole is worth two on the bush.

Round robin is a shy bird.

There's a shiny lining to every hat.

The longest dinner will come to an end.[Pg 96]

You must take the pips with the orange.

It's a wise dentist that knows his own teeth.

No rose without a gardener.

Better to marry in May than not to marry at all.

Save sovereigns, spend guineas.

Too many followers spoil the cook. (N.B. This is not nonsense.)

Said at the Academy.—Punch doesn't care who said it. It was extremely rude to call the commission on capital punishments the hanging committee.

The Grammar of Art.—"Art," spell it with a big or little "a", can never come first in any well-educated person's ideas. "I am" must have the place of honour; then "Thou Art!" so apostrophised, comes next.

Scrumble. "Been to see the old masters?"

Stippleton (who has married money). "No. Fact is"—(sotto voce)—"I've got quite enough on my hands with the old missus!"

Question. Has the anxious parent been to see his child's portrait?

Answer. He has seen it.

Q. Did he approve of it?

A. He will like it better when I have made some slight alterations.

Q. What are they?

A. He would like the attitude of the figure altered, the position of the arms changed, the face turned the other way, the hair and eyes made a different colour, and the expression of the mouth improved.

Q. Did he make any other suggestions?

A. Yes; he wishes to have the child's favourite pony and Newfoundland dog put in, with an indication of the ancestral home in the back-ground.

Q. Is he willing to pay anything extra for these additions?

A. He does not consider it necessary.

Q. Are you well on with your Academy picture?

A. No; but I began the charcoal sketch yesterday.[Pg 100]

Q. Have you secured the handsome model?

A. No; the handsome model has been permanently engaged by the eminent R.A.

Q. Under these circumstances, do you still expect to get finished in time?

A. Yes; I have been at this stage in February for as many years as I can remember, and have generally managed to worry through somehow.

Whenever the "Reduced Prizefighters" take a benefit at a theatre, the play should be The Miller and his Men.

A Nice Man.—Mr. Swiggins was a sot. He was also a sloven. He never had anything neat about him but gin.

"Hung, Drawn, and Quartered."—(Mr. Punch's sentence on three-fourths of the Academicians' work "on the line.")—Very well "hung"; very ill "drawn"; a great deal better "quartered" than it deserves.

When he magnanimously consents to go on the platform at a conjuring performance, and unwonted objects are produced from his inside pockets.

Celebrated Minor Poet. "Ah, hostess, how 'do? Did you get my book I sent you yesterday?"

Hostess. "Delightful! I couldn't sleep till I'd read it!"

The Infant Prodigy has reached the middle of an exceedingly difficult pianoforte solo, and one of those dramatic pauses of which the celebrated composer is so fond has occurred. Kindly but undiscerning old Lady. "Play something you know, dearie."

Distinguished Foreigner (hero of a hundred duels). "It is delightful, mademoiselle. You English are a sporting nation."

Fair Member. "So glad you are enjoying it. By the way, Monsieur le Marquis, have they introduced fencing into France yet?"

Patron. "When are yer goin' to start my wife's picture and mine? 'Cause, when the 'ouse is up we're a goin'——"

Artist. "Oh, I'll get the canvases at once, and——"

Patron (millionaire). "Canvas! 'Ang it!—none o' yer canvas for me! Price is no objec'! I can afford to pay for something better than canvas!!" [Tableau!

Amateur Artist (to the carrier). "Did you see my picture safely delivered at the Royal Academy?"

Carrier. "Yessir, and mighty pleased they seemed to be with it—leastways, if one may jedge, sir. They didn't say nothin'—but—lor' how they did laugh!"

Artist (who has recommended model to a friend). "Have you been to sit to Mr. Jones yet?"

Model. "Well, I've been to see him; but directly I got into his studio, 'Why,' he said, 'you've got a head like a Botticelli.' I don't know what a Botticelli is, but I didn't go there to be called names, so I come away!"

Art Student (engaging rooms). "What is that?"

Landlady. "That is a picture of our church done in wool by my daughter, sir. She's subject to art, too."

"I always buy your paper my dear Horace," said the old lady, "although there is much in it I cannot approve of. But there is one thing that puzzles me extremely."

"Yes, aunt?" said the Sub-Editor meekly, as he sipped his tea.

"Why, I notice that the contents bill invariably has one word calculated to stimulate the morbid curiosity of the reader. An adjective."

"Circulation depends upon adjectives," said the Sub-Editor.

"I don't think I object to them," the old lady replied; "but what I want you to tell me is how you choose them. How do you decide whether an occurrence is 'remarkable' or 'extraordinary,' 'astounding' or 'exciting,' 'thrilling' or 'alarming,' 'sensational' or merely 'strange,' 'startling' or 'unique'? What tells you which word to use?"

"Well, aunt, we have a system to indicate the adjective to a nicety; but——"

"My dear Horace, I will never breathe a word.[Pg 112] You should know that. No one holds the secrets of the press more sacred than I."

The Sub-Editor settled himself more comfortably in his chair.

"You see, aunt, the great thing in an evening paper is human interest. What we want to get is news to hit the man-in-the-street. Everything that we do is done for the man-in-the-street. And therefore we keep safely locked up in a little room a tame man of this description. He may not be much to look at, but his sympathies are right, unerringly right. He sits there from nine till six, and has things to eat now and then. We call him the Thrillometer."

"How wonderful! How proud you should be Horace, to be a part of this mighty mechanism, the press."

"I am, aunt. Well, the duties of the Thrillometer are very simple. Directly a piece of news comes in, it is the place of one of the Sub-Editors to hurry to the Thrillometer's room and read it to him. I have to do this."

"Poor boy. You are sadly overworked, I fear."

"Yes, aunt. And while I read I watch his face, Long study has told me exactly what degree of interest is excited within him by the announcement. I know instantly whether his expression means 'phenomenal' or only 'remarkable,' whether 'distressing' or only 'sad,' whether——"

"Is there so much difference between 'distressing' and 'sad,' Horace?"

"Oh, yes, aunt. A suicide in Half Moon Street[Pg 115] is 'distressing'; in the City Road it is only 'sad.' Again, a raid on a club in Whitechapel is of no account; but a raid on a West-End club is worth three lines of large type in the bill, above Fry's innings."

"Do you mean a club in Soho when you say West-End?"

"Yes, aunt, as a rule."

"But why do you call that the West-End?"

"That was the Thrillometer's doing, aunt. He fell asleep over a club raid, and a very good one too, when I said it was in Soho; but when I told[Pg 116] him of the next—also in Soho, chiefly Italian waiters—and said it was in the West-End, his eyes nearly came out of his head. So you see how useful the Thrillometer can be."

"Most ingenious, Horace. Was this your idea?"

"Yes, aunt."

"Clever boy. And have the other papers adopted it?"

"Yes, aunt. All of them."

"Then you are growing rich, Horace?"

"No, no, aunt, not at all. Unfortunately I lack the business instinct. Other people grow rich on my ideas. In fact, so far from being rich, I was going to venture to ask you——"

"Tell me more about the Thrillometer," said the old lady briskly.

All the way from the National Gallery

Unto the Royal Academy

As I walked, I was guilty of raillery,

Which I felt was very bad o' me.

Thinking of art's disasters,

Still sinking to deeper abysses,

I said, "From the Old Masters

Why go to the new misses?"

He. "Awfully jolly concert, wasn't it? Awfully jolly thing by that fellow—what's his name?—something like Doorknob."

She. "Doorknob! Whom do you mean? I only know of Beethoven, Mozart, Wagner, Handel——"

He. "That's it! Handel. I knew it was something you caught hold of!"

Lecturer. "Now let anyone gaze steadfastly on any object—say, for instance, his wife's eye—and he'll see himself looking so exceedingly small, that——"

Strong-minded Lady (in front row). "Hear! Hear! Hear!"

"After the Fair." (Country cousin comes up in August to see the exhibition of pictures at the Royal Academy!).—Porter. "Bless yer 'art, we're closed!"

Country Cousin. "Closed! What! didn't it pay?!!"

Jones. "How is it we see you so seldom at the club now?"

Old Member. "Ah, well, you see, I'm not so young as I was; and I've had a good deal of worry lately; and so, what with one thing and another, I've grown rather fond of my own society."

Jones. "Epicure!"

German Dealer "Now, mein Herr! You've chust heerd your lofely blaying rebroduced to berfection! Won't you buy one?"

Amateur Flautist. "Are you sure the thing's all right?"

German Dealer. "Zertainly, mein Herr."

Amateur Flautist. "Gad, then, if that's what my playing is like, I'm done with the flute for ever."

Surveyor of Taxes (to literary gent). "But surely you can arrive at some estimate of the amount received by you during the past three years for example. Don't you keep books?"

Literary Gent. (readily). "Oh dear no. I write them!"

Surveyor. "Ahem—I mean you've got some sort of accounts——"

Literary Gent. "Oh yes, lots"—(Surveyor brightens up)—"unpaid!"

"There's a boy wants to see you, sir." "Has he got a bill in his hand?" "No, sir." "Then he's got it in his pocket! Send him away!"

He. "By Jove, it's the best thing I've ever painted!—and I'll tell you what; I've a good mind to give it to Mary Morison for her wedding present!"

His Wifey. "Oh, but, my love, the Morisons have always been so hospitable to us! You ought to give her a real present, you know—a fan, or a scent-bottle, or something of that sort!"

Mr. Punch, having read the latest book on the way to write for the press, feels that there is at least one important subject not properly explained therein: to wit, the covering letter. He therefore proceeds to supplement this and similar books.... It is, however, when your story is written that the difficulties begin. Having selected a suitable editor, you send him your contribution accompanied by a covering letter. The writing of this letter is the most important part of the whole business. One story, after all, is very much like another (in your case, probably, exactly like another), but you can at least in your covering letter show that you are a person of originality.

Your letter must be one of three kinds: pleading, peremptory, or corruptive. I proceed to give examples of each.

Dear Mr. Editor,—I have a wife and seven starving children; can you possibly help us by[Pg 130] accepting this little story of only 18,000 (eighteen thousand) words? Not only would you be doing a work of charity to one who has suffered much, but you would also, I venture to say, be conferring a real benefit upon English literature—as I have already received the thanks of no fewer than thirty-three editors for having allowed them to peruse this manuscript.

Yours humbly,

P.S.—My youngest boy, aged three, pointed to his little sister's Gazeka toy last night and cried "De editor!" These are literally the first words that have passed his lips for three days. Can you stand by and see the children starve?

Sir,—Kindly publish at once and oblige

Yours faithfully,

P.S.—I shall be round at your office to-morrow about an advertisement for some 600 lb. bar-bells, and will look you up.

Dear Mr. Smith,—Can you come and dine with us quite in a friendly way on Thursday at eight? I want to introduce you to the Princess of Holdwig-Schlosstein and Mr. Alfred Austin, who are so eager to meet you. Do you know I am really a little frightened at the thought of meeting such a famous editor? Isn't it silly of me?

Yours very sincerely,

P.S.—I wonder if you could find room in your splendid little paper for a silly story I am sending you. It would be such a surprise for the Duke's birthday (on Monday).—E. M.

Before concluding the question of the covering letter I must mention the sad case of my friend Halibut. Halibut had a series of lithographed letters of all kinds, one of which he would enclose with every story he sent out. On a certain occasion he wrote a problem story of the most advanced kind; what, in fact, the reviewers call a "strong" story. In sending this to the editor of a famous[Pg 134] magazine his secretary carelessly slipped in the wrong letter:

"Dear Mr. Editor," it ran, "I am trying to rite you a littel story, I do hope you will like my little storey, I want to tell you about my kanary and my pussy cat, it's name is Peggy and it has seven kitens, have you any kitens, I will give you one if you print my story,

"Your loving little friend,

The Enraged Musician.—(A Duologue.)

Composer. Did you stay late at Lady Tittup's?

Friend. Yes. Heard Miss Bang play again. I was delighted with her execution.

Composer. Her execution! That would have pleased me; she deserved it for having brutally murdered a piece of mine.

The Gentility of Speech.—At the music halls visitors now call for "another acrobat," when they want a second tumbler.

Portrait of a gentleman who proposes to say he was detained in town on important business.

Dingy Bohemian. "I want a bath Oliver."

Immaculate Servitor. "My name is not Oliver!"

Indigo Brown takes his picture, entitled "Peace and Comfort," to the R.A. himself, as he says, "Those picture carts are certain to scratch it," and, with the assistance of his cabby, adds the finishing touches on his way there!

Miss Sere. "Ah, Mr. Brown, if you could only paint me as I was ten years ago!"

Our Portrait Painter (heroically). "I am afraid children's portraits are not in my line."

The Prodigal. "Well, dad, here I am, ready to go into the office to-morrow. I've given up my studio and put all my sketches in the fire."

Fond Father. "That's right, 'Arold. Good lad! Your 'art's in the right place, after all!"

Brown (as Hamlet) to Jones (as Charles the Second). "'Normous amount of taste displayed here to-night!"

Brown (trying to find something to admire in Smudge's painting). "By Jove, old chap, those flowers are beautifully put in!"

Smudge. "Yes; my old friend—Thingummy—'R.A.' you know, painted them in for me."

Scene—Miss Semple and Dawber, standing near his picture.

Miss Semple. "Why, there's a crowd in front of Madder's picture!"

Dawber. "Someone fainted, I suppose!"

["Incapacity for work has come to be accepted as the hall-mark of genius.... The collector wants only the thing that is rare, and therefore the artist must make his work as rare as he can."—Daily Chronicle.]

Josephine found me stretched full length in a hammock in the garden.

"Why aren't you at work?" she asked; "not feeling seedy, I hope?"

"Never better," said I. "But I've been making myself too cheap."

"We couldn't possibly help going to the Joneses last night, dear."

"Tush," said I. "I mean there is too much of me."

"I don't quite understand," she said; "but there certainly will be if you spend your mornings lolling in that hammock."

The distortive wantonness of this remark left me cold.

"I have made up my mind," I continued, quite seriously, "to do no more work for a considerable time."

"But, my dear boy, just think——"[Pg 144]

"I'm going to make myself scarce," I insisted.

"Geoffrey!" she exclaimed, "I knew you weren't well!"

I released myself.

"Josephine," I said solemnly, "those estimable persons who collect my pictures will think nothing of them if they become too common."

"How do you know there are such persons?" she queried.

"I must decline to answer that question," I replied; "but if there are none it is because my work is not yet sufficiently rare and precious. I propose to work no more—say, for six or seven years. By that time my reputation will be made, and there will be the fiercest competition for the smallest canvas I condescend to sign."

She kissed me.

"I came out for the housekeeping-money," she remarked simply.

I went into the house to fetch the required sum, and, by some means I cannot explain, got to work again upon the latest potboiler.

Duchess (with every wish to encourage conversation, to gentleman just introduced). "Your name is very familiar to me indeed for the last ten years."

Minor Poet (flattered). "Indeed, Duchess! And may I ask what it was that first attracted you?"

Duchess. "Well, I was staying with Lady Waldershaw, and she had a most indifferent cook, and whenever we found fault with any dish she always quoted you, and said that you liked it so much!"

Wife of your Bussum. "Oh! I don't want to interrupt you, dear. I only want some money for baby's socks—and to know whether you will have the mutton cold or hashed."

Hearty Friend (meeting Operatic Composer). Hallo, old man, how are you? Haven't seen you for an age! What's your latest composition?

Impecunious Musician (gloomily). With my creditors. [Exeunt severally.

Guest (after a jolly evening). "Good night, ol' fellah—I'll leave my boosh oushide 'door——"

Bohemian Host. "Au' right, m' boy—(hic)—noborry'll toussh 'em—goo' light!!" [Exeunt.

Now that the painful month of suspense in Studioland is at an end, it behoves us to apply our most soothing embrocation to the wounded feelings of geniuses whose works have boomeranged their way back from Burlington House. Let them remember:

That very few people really look at the pictures in the Academy—they only go to meet their friends, or to say they have been there.

That those who do examine the works of art are wont to disparage the same by way of showing their superior smartness.

That one picture has no chance of recognition with fourteen hundred others shouting at it.

That all the best pavement-artists now give "one-man" shows. They can thus select their own "pitch," and are never ruthlessly skied.

That photography in colours is coming, and then the R.A. will have to go.

That Rembrandt, Holbein, Rubens and Vandyck were never hung at the summer exhibition.[Pg 150]

That Botticelli, Correggio and Titian managed to rub along without that privilege.

That the ten-guinea frame that was bought (or owed for) this spring will do splendidly next year for another masterpiece.

That the painter must have specimens of his best work to decorate the somewhat bare walls of his studio.

That the best test of a picture is being able to live with it—or live it down—so why send it away from its most lenient critic?

That probably the chef-d'œuvre sent in was shown to the hanging committee up-side down.

That, supposing they saw it properly, they were afraid that its success would put the Academy to the expense of having a railing placed in front.

And finally, we would remind the rejected one that, after all, his bantling has been exhibited in the R.A.—to the president and his colleagues engaged in the work of selection. Somebody at least looked at it for quite three seconds.

Extract from Lady's Correspondence. "—— In fact, our reception was a complete success. We had some excellent musicians. I daresay you will wonder where we put them, with such a crowd of people; but we managed capitally!"

Vandyke Browne. "Peace, my dear lady, peace and refinement, those are the two essentials in an artist's surroundings." [Enter Master and Miss Browne. Tableau!

Little Smudge. "Of course, I know perfectly well my style isn't quite developed yet, but I feel I am, if I might so express it, in a transition stage, don't you know," Brother Brush ("skied" this year). "Ah! I see, going from bad to worse!"

["With this little instrument that rests so lightly in the hand, whole nations can be moved.... When it is poised between thumb and finger, it becomes a living thing—it moves with the pulsations of the living heart and thinking brain, and writes down, almost unconsciously, the thoughts that live—the words that burn.... It would be difficult to find a single newspaper or magazine to which we could turn for a lesson in pure and elegant English."—Miss Corelli in "Free Opinions Freely Expressed."]

O magic pen, what wonders lie

Within your little length!

Though small and paltry to the eye

You boast a giant's strength.

Between my finger and my thumb

A living creature you become,

And to the listening world you give

"The words that burn—the thoughts that live."

Oft, when the sacred fire glows hot,

Your wizard power is proved:

You write till lunch, and nations not

Infrequently are moved;

'Twixt lunch and tea perhaps you damn

For good and all, some social sham,

And by the time I pause to sup—

Behold Carnegie crumpled up!

Through your unconscious eyes I see

Strange beauty, little pen!

You make life exquisite to me,

If not to other men.

You fill me with an inward joy

No outward trouble can destroy,

Not even when I struggle through

Some foolish ignorant review;

Nor when the press bad grammar scrawls

In wild uncultured haste,

And which intolerably galls

One's literary taste.

What are the editors about,

Whom one would think would edit out

The shocking English and the style

Which every page and line defile?

There is, alas! no magazine,

No paper that one knows

To which a man could turn for clean

And graceful English prose;

Not even, O my pen, though you

Yourself may write for one or two,

And lend to them a style, a tone,

A grammar that is all your own.

I see the shadows of decay

On all sides darkly loom;

Massage and manicure hold sway,

Cosmetics fairly boom;

Old dowagers and budding maids

Alike affect complexion-aids,

While middle age with anxious care

Dyes to restore its dwindling hair.

The time is out of joint, but still

I am not hopeless quite

So long as you exist, my quill,

Once more to set it right.

Woman will cease from rouge, I think,

Man pour his hair-wash down the sink,

If you will yet consent to give

"The words that burn—the thoughts that live."

As the publishing season will soon be in full play—which means that there will be plenty of work—we suggest the following as titles of books, to succeed the publication of "People I have Met," by an American:—

People I have taken into Custody, by a Policeman.

People that have Met me Half-way, by an Insolvent.

People I have Splashed, by a Scavenger.

People I have Done, by a Jew Bill-discounter.

People I have Abused, by a 'Bus Conductor.

People I have Run Over, by a Butcher's Boy.

People I have Run Against, by a Sweep.

Mrs. Mudge. "I do admire the women you draw, Mr. Penink. They're so beautiful and so refined! Tell me, who is your model?" [Mrs. Mudge rises in Mrs. Penink's opinion.]

Penink. "Oh, my wife always sits for me!"

Mrs. Mudge (with great surprise). "You don't say so! Well, I think you're one of the cleverest men I know!" [Mrs. Penink's opinion of Mrs. Mudge falls below zero.

George (Itinerant Punch-and-Judy Showman). "I say, Bill, she do draw!"

Bill (his partner, with drum and box of puppets). "H'm—it's more than we can!"

Brown (as he was leaving our Art Conversazione, after a rattling scramble in the cloak-room). "Confound it! Got my own hat, after all!"

Eccentric Old Gent (whose pet aversion is a dirty child). "Go away, you dirty girl, and wash your face!"

Indignant Youngster. "You go 'ome, you dirty old man, and do yer 'air!"

Musical Fact.—People are apt to complain of the vile tunes that are played about the streets by grinding organs, and yet they may all be said to be the music of Handle.

Photographer. "I think this is an excellent portrait of your wife."

Mr. Smallweed. "I don't know—sort of repose about the mouth that somehow doesn't seem right."

Johnnie (who finds that his box, £20, has been appropriated by "the Fancy"). "I beg your pardon, but this is my box!"

Bill Bashford. "Oh, is it? Well, why don't you tike it?"

Ugly Man (who thinks he's a privileged wag, to artist). "Now, Mr. Daubigny, draw me."

Artist (who doesn't like being called Daubigny, and whose real name is Smith). "Certainly. But you won't be offended if it's like you. Eh?"

Scrimble. "So sorry I've none of my work to show you. Fact is, I've just sent all my pictures to the Academy."

Mrs. Macmillions. "What a pity! I did so much want to see them. How soon do you expect them back?"

Chloroform. Invaluable to writers of sensational stories. Every high-class fictionary criminal carries a bottle in his pocket. A few drops, spread on a handkerchief and waved within a yard of the hero's nose, will produce a state of complete unconsciousness lasting for several hours, within which time his pockets may be searched at leisure. This property of chloroform, familiar to every expert novelist, seems to have escaped the notice of the medical profession.

Consumption. The regulation illness for use in tales of mawkish pathos. Very popular some years ago, when the heroine made farewell speeches in blank verse, and died to slow music. Fortunately, however, the public has lost its fondness for work of this sort. Consumption at its last stage is easily curable (in novels) by the reappearance of a hero supposed to be dead. Two pages later the heroine will gain strength in a way which her doctors—not unnaturally—will describe as "perfectly[Pg 168] marvellous." And in the next chapter the marriage-bells will ring.

Doctor. Always include a doctor among your characters. He is quite easy to manage, and invariably will belong to one of these three types: (a) The eminent specialist. Tall, imperturbable, urbane. Only comes incidentally into the story. (b) Young, bustling, energetic. Not much practice, and plenty of time to look after other people's affairs. Hard-headed and practical. Often the hero's college friend. Should be given a pretty girl to marry in the last chapter. (c) The old family doctor. Benevolent, genial, wise. Wears gold-rimmed spectacles, which he has to take off and wipe at the pathetic parts of the book.

Fever. A nice, useful term for fictionary illnesses. It is best to avoid mention of specific symptoms, beyond that of "a burning brow," though, if there are any family secrets which need[Pg 170] to be revealed, delirium is sure to supervene at a later stage. Arthur Pendennis, for instance, had fictional "fever," and baffled doctors have endeavoured ever since to find out what really was the matter with him. "Brain-fever," again, is unknown to the medical faculty, but you may safely afflict your intellectual hero with it. The treatment of fictionary fever is quite simple, consisting solely of frequent doses of grapes and cooling drinks. These will be brought to the sufferer by the heroine, and these simple remedies administered in this way have never been known to fail.

Fracture. After one of your characters has come a cropper in the hunting-field he will be taken on a hurdle to the nearest house: usually, by a strange coincidence, the heroine's home. And[Pg 172] he will be said to have sustained "a compound fracture"—a vague description which will quite satisfy your readers.

Gout. An invaluable disease to the humorist. Remember that heroes and heroines are entirely immune from it, but every rich old uncle is bound to suffer from it. The engagement of his niece to an impecunious young gentleman invariably coincides with a sharp attack of gout. The humour of it all is, perhaps, a little difficult to see, but it never fails to tickle the public.

Heart Disease. An excellent complaint for killing off a villain. If you wish to pave the way for it artistically, this is the recognised method: On page 100 he will falter in the middle of a sentence, grow pale, and press his hand sharply to his side. In a moment he will have recovered,[Pg 174] and will assure his anxious friends that it is nothing. But the reader knows better. He has met the same premonitory symptoms in scores of novels, and he will not be in the least surprised when, on the middle of page 250, the villain suddenly drops dead.

Nervous.—Mrs. Malaprop was induced to go to a music hall the other evening. She never means to set foot in one again. The extortions some of the performers threw themselves into quite upset her.

Motto for a model Music-hall Entertainment.—"Everything in its 'turn' and nothing long."

His Cousins. "We sent off the wire to stop your model coming. But you had put one word too many—so we struck it out."

Real Artist. "Oh, indeed. What word did you strike out?"

His Cousins. "You had written 'he wasn't to come, as you had only just discovered you couldn't paint to-day.' So we crossed out 'to-day.'"

Artist (to customer, who has come to buy on behalf of a large furnishing firm in Tottenham Court Road): "How would this suit you? 'Summer'!"

Customer: "H'm—'Summer.' Well, sir, the fact is we find there's very little demand for green goods just now. If you had a line of autumn tints now—that's the article we find most sale for among our customers!"

Our Amateur Romeo (who has taken a cottage in the country, so as to be able to study without interruption). "Arise, fair sun, and kill the envious moon——"

Owner of rubicund countenance (popping head over the hedge), "Beg pardon, zur! Be you a talkin' to Oi, zur?"

MacStodge (Pictor ignotus). "Who's that going out?"

O'Duffer (Pictor ignotissimus). "One Ernest Raphael Sopely, who painted Lady Midas!"

MacStodge. "Oh, the artist!"

O'Duffer. "No. The Royal Academician!"

First Bohemian (to second ditto). "I can't for the life of me think why you wasted all that time haggling with that tailor chap, and beating him down, when you know, old chap, you won't be able to pay him at all."

Second Bohemian. "Ah, that's it! I have a conscience. I want the poor chap to lose as little as possible!"

Genial Doctor (after laughing heartily at a joke of his patient's). "Ha! ha! ha! There's not much the matter with you! Though I do believe that if you were on your death-bed you'd make a joke!"

Irrepressible Patient. "Why, of course I should. It would be my last chance!"

She (to Raphael Greene, who paints gems for the R.A. that are never accepted). "I do hope you'll be hung this year. I'm sure you deserve to be!"

She (reads). "There are upwards of fifty English painters and sculptors now in Rome——"

He (British Philistine—served on a late celebrated jury!). "Ah! no wonder we couldn't get that scullery white-washed!"

Devoted little wife (to hubbie, who has been late at the club). "Now, dear, see, your breakfast is quite ready. A nice kipper, grilled chicken and mushrooms with bacon, poached eggs on toast—tea and coffee. Anything else you'd like, dearie?"

Victim of last night (groans). "Yes—an appetite!" [Collapses.

Showman of Travelling Menagerie. "Now, ladies and gentlemen, we come to the most interesting part of the 'ole exhibition! Seven different species of hanimals, in the same cage, dwellin' in 'armony. You could see them with the naked heye, only you have come too late. They are all now inside the lion!"

In the Billiard Room.—Major Carambole. I never give any bribes to the club servants on principle.

Captain Hazard. Then I suppose the marker looks on the tip of your cue without interest.

Seedy Individual (to Knowing One). "D'yer want to buy a diamond pin cheap?"

Knowing One. "'Ere, get out of this! What d'you take me for? A juggins?"

S. I. "Give yer my word it's worth sixty quid if it's worth a penny. And you can 'ave it for a tenner."

K. O. "Let's 'ave a look at it. Where is it?"

S. I. "In that old gent's tie. Will yer 'ave it?"

"Yew harxed me woy hoi larved when larve should be

A thing hun-der-eamed hof larve twixt yew han me.

Yew moight hin-tereat the sun tew cease tew she-oine

Has seek tew sty saw deep a larve has moine."

["We have regularly attended the Academy now for many years, but never do we remember such a poor show of portraits; they cannot prove to be otherwise than the laughing-stock of tailors and their customers."—Tailor and Cutter.]

The tailor leaned upon his goose,

And wiped away a tear:

"What portraits painting-men produce,"

He sobbed, "from year to year!

These fellows make their sitters smile

In suits that do not fit,

They're wrongly buttoned, and the style

Is not the thing a bit.

"Oh, artist I'm an artist too!

I bid you use restraint,

And only show your sitters, do,

In fitting coats of paint;

In vain you crown those errant seams

With smiles that look ethereal,

For man may be the stuff of dreams—

But dreams are not material."

Frame-maker (to gifted amateur, who is ordering frames for a few prints and sketches). "Ah, I suppose you want something cheap an' ordinary for this?"

[N.B.—"This" was a cherished little sketch by our amateur himself.

Not quite the Same.—Scene: Exhibition of Works of Art.

Dealer (to friend, indicating stout person closely examining a Vandyke). Do you know who that is? I so often see him about.

Friend. I know him. He's a collector.

Dealer (much interested). Indeed! What does he collect? Pictures?

Friend. No. Income tax.

[Exeunt severally.

Art Class.—Inspector. What is a "landscape painter"?

Student. A painter of landscapes.

Inspector. Good. What is an "animal painter"?

Student. A painter of animals.

Inspector. Excellent. What is a "marine painter"?

Student. A painter of marines.

Inspector. Admirable! Go and tell it them. Call next class.

[Exeunt students.

Anxious Musician (in a whisper, to Mrs. Lyon Hunter's butler). "Where's my cello?"

Butler (in stentorian tones, to the room). "Signor Weresmicello!"

Enthusiastic Briton (to seedy American, who has been running down all our national monuments). "But even if our Houses of Parliament 'aren't in it,' as you say, with the Masonic Temple of Chicago, surely, sir, you will admit the Thames Embankment, for instance——"

Seedy American. "Waal, guess I don't think so durned much of your Thames Embankment, neither. It rained all the blarmed time the night I slep on it."

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Mr. Punch in Bohemia, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MR. PUNCH IN BOHEMIA ***

***** This file should be named 35874-h.htm or 35874-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/3/5/8/7/35874/

Produced by Neville Allen, David Edwards and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.net/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.net),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.