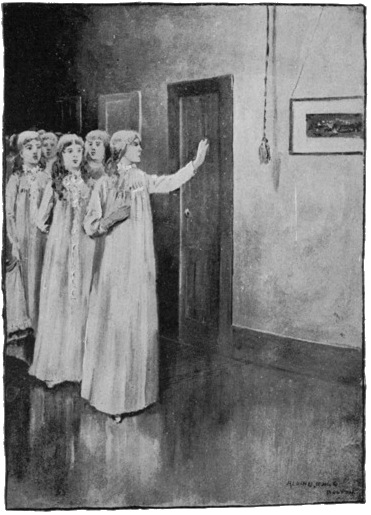

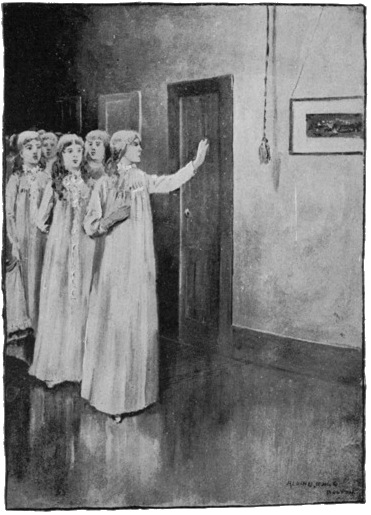

Twenty white-robed girls in ghost-like procession headed for the Fräulein’s room.—Page 189. Miss Ashton’s New Pupil.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Miss Ashton's New Pupil, by Mrs. S. S. Robbins

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: Miss Ashton's New Pupil

A School Girl's Story

Author: Mrs. S. S. Robbins

Release Date: May 10, 2009 [EBook #28743]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MISS ASHTON'S NEW PUPIL ***

Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Twenty white-robed girls in ghost-like procession headed for the Fräulein’s room.—Page 189. Miss Ashton’s New Pupil.

MISS ASHTON’S NEW PUPIL

A SCHOOL GIRL’S STORY

By MRS. S. S. ROBBINS

Author of “Hulda Brent’s Will,” “Paul’s Angel,” etc., etc.

A. L. BURT, PUBLISHER,

52-58 Duane Street, New York.

Copyright, 1892,

By BRADLEY & WOODRUFF.

All Rights Reserved

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Miss Ashton Receives a Letter. | 5 |

| II. | Marion Enters School. | 9 |

| III. | Gladys Has a Room-Mate. | 16 |

| IV. | Settling Down to Work. | 22 |

| V. | Mrs. Parke’s Letter. | 27 |

| VI. | School Cliques. | 33 |

| VII. | Aids to Education. | 40 |

| VIII. | Demosthenic Club. | 46 |

| IX. | Miss Ashton’s Advice. | 55 |

| X. | Choosing a Profession. | 62 |

| XI. | Visit of Cousin Abijah. | 68 |

| XII. | The Tableaux. | 73 |

| XIII. | Gladys Leaves the Club. | 78 |

| XIV. | Kate Underwood’s Apologies. | 84 |

| XV. | Miss Ashton’s Friday Night. | 91 |

| XVI. | Storied West Rock. | 98 |

| XVII. | November Snowstorm. | 105 |

| XVIII. | The Sleigh-Ride. | 112 |

| XIX. | Detectives at Work. | 120 |

| XX. | Repentance. | 128 |

| XXI. | Accepting a Thanksgiving Invitation. | 136 |

| XXII. | Aunt Betty’s Reception of Her Guest. | 143 |

| XXIII. | The Academy Girl’s Thanksgiving at the Old Homestead. | 150 |

| XXIV. | Marion’s Repentance. | 160 |

| XXV. | Diphtheria. | 167 |

| XXVI. | Christmas Coming. | 175 |

| XXVII. | Christmas in the Academy. | 183 |

| XXVIII. | Fräulein’s Gymnastics. | 191 |

| XXIX. | Women’s Work. | 200 |

| XXX. | Deceit. | 208 |

| XXXI. | Marion’s Letter from Home. | 216 |

| XXXII. | Penitent. | 223 |

| XXXIII. | Spring Vacation. | 231 |

| XXXIV. | Nemesis. | 236 |

| XXXV. | Farewell Words. | 244 |

| XXXVI. | Women’s Work. | 251 |

| XXXVII. | Commencement. | 260 |

MISS ASHTON’S NEW PUPIL.

Miss Ashton, principal of the Montrose Academy, established for the higher education of young ladies, sat with a newly arrived letter in her hand, looking with a troubled face over its contents.

Letters of this kind were of constant occurrence, but this had in it a different tone from any she had previously received.

“It’s tender and true,” she said to herself. “How sorry I am, I can do nothing for her!”

This was the letter:—

Dear Miss Ashton,—I have a daughter Marion, now sixteen years old. Developing at this age what we think rather an unusual amount of talent, we are desirous to send her to a good school at the East.

We have been at the West twenty years as Home Missionaries. When I tell you that, I need not add that we have been made very happy by being able to save money enough to give Marion at least a year under your kind care, if you can receive her into your school.

I think I can safely promise you that she will be faithful and industrious; and I earnestly hope that the lovely Christian character 6 she has sustained at home, may deepen and brighten in the new life which will open to her in the East.

May I ask your patience while she is accustoming herself to it; of your kindness I am well assured.

Truly yours,

E. G. Parke.

“The child of a poor, far western missionary, so different from the class of girls that she will be with here,” thought Miss Ashton as she slowly folded the letter.

She sat for some time thinking over its contents, then she took her pen, and wrote:—

Dear Mrs. Parke,—Send your daughter to me. I have great interest in, and sympathy with, all Home Missionary work. I wish I could do something to lighten the expenses she must incur; but this is a chartered institution, and at present all the places to be filled by those who need assistance have been taken. I will, however, bear her in mind; and should she prove a good scholar, exemplary in her behavior, I may be able to render her in the future some acceptable assistance.

Wishing you all success in your trying and arduous life, and the help of the great Helper,

I am, truly yours,

C. S. Ashton.

Miss Ashton did not seal this note; she tossed it upon her desk, meaning to look it over before it was mailed; but she had no time, and, with many misgivings as to what might come of it, she allowed it to go as it was.

Her school had never been fuller than it promised to be on the opening of this new year. Through the summer vacation letters had been coming to her from all parts of the country asking to put girls who 7 had finished graded and high school education under her care. Established for many years, the academy had grown from what, in the religious world, was considered a “missionary training-school,” and from which many able and faithful women had gone forth to win laurels in the over-ripe harvest fields, to a school better adapted to the wants of the nineteenth century.

While it held its religious prestige, it also offered unusual advantages to that important and numerous class of girls who, not wishing a college education, were yet desirous to spend the years that should change them from girls into women in preparation for a future great in its aims, and also great in its results.

Miss Ashton, large-hearted and strong-headed, seeing wisely into this future, had succeeded in offering to this class exactly what it had demanded.

Ably seconded by an efficient and generous board of trustees, with ample funds, excellent teachers to assist her, a convenient and handsome building in which to hold the school, she had readily made it a success. There were more applications for admittance than she could find room for; indeed, every available corner of the house had been promised when she received Mrs. Parke’s letter.

Sometimes it happened that a scholar for some unforeseen reason failed to appear; that might make an opening for Marion. She wanted this Western girl; the missionary spirit of olden times came back 8 to her with a warmth and freshness it would have cheered the hearts of the long-absent ones in heathen lands to know. The crowd of scholars began to gather. They came from the north and the south, the east and the west, with a remarkable promptness. On the day for the opening of the term every room was full, and many who had delayed applying for places—taking it for granted there was always a vacancy—were sent disappointed away.

There seemed to be positively no spot for Marion; and, in spite of all the cares and perplexities which each day brought her, Miss Ashton could not forget it. It became a positive source of worry to her before she received a letter stating the day on which Marion would arrive.

“That’s not a good beginning, to be a week after the opening of the term,” she thought. “I hope she will bring a good excuse.”

It was a beautiful September twilight when a young girl came timidly into the main entrance of the Young Ladies’ Academy at Montrose.

Six days and four nights ago she had left her home in Oregon, delayed by the sickness of one of the companions under whose escort she was to come to Massachusetts.

Before this journey she had never been more than ten miles from home, and it was a wonderful new world into which the cars so quickly brought her.

Mountains, plains, rivers, cities, villages, seemed to fly by her as the train dashed along. She had no time to miss the familiar scenes of her own home.

The flat prairie, over whose long reaches gay flowers blossomed, the little villages dotted here and there, with now and then a small, white steeple pointing heavenward,—her father’s church among them, with the neat parsonage, so much of which he had built with his own hand, and the dear ones she had left behind her there.

To-day she had reached her destination, and a smiling girl had met her at the door and ushered her into the lower corridor of the academy. 10

It was just after tea, an hour given up to social enjoyment, and the corridor was full of young girls, busy and noisy.

The stranger shrank back into the recess of the door; she hoped no one would see her: if she could only escape until the principal came, how glad she should be!

Little groups kept constantly passing her; many from among them turned their heads and looked at her inquiringly; some smiled and bowed, but no one spoke, until a tall girl who had passed and repassed her a number of times left her party and came to her.

“You are our two hundredth!” she said, holding her hand out cordially toward her. “We are glad you have come! Now we are the largest number that have ever been in this school at one time. Shall I take you to Miss Ashton?”

Marion held very tight to the hand that was given her as they passed together down through the lines of scholars toward the principal’s room. More smiles and cheery nods met her, and now and then she caught “two hundredth” as she passed.

A knock at a door was immediately answered by a pleasant “Come in.”

“Oh, it’s you, Dorothy, is it? I’m always glad to see you,” said Miss Ashton, rising from the table at which she had been writing.

“I’ve brought you your new pupil,” said Dorothy.

“And I’m very glad to see her. It is Marion 11 Parke, I presume. You have had a long, hard journey, but you look so well I need not ask how you have borne it.”

As she was giving Marion this welcome, Miss Ashton, with the quick look by which her long experience had accustomed her to judging something of character, saw in the timid new pupil a very different girl from what in her troubled thoughts of her she had expected her to be.

Two large gray eyes from under long, drooping eyelids met hers with an appealing look; lips trembled sensitively as they tried to answer her, and a delicate color came slowly up over the rounded cheeks.

“I am very sorry to be late,” Marion said with a self-possession that belied the timidity her face expressed; “but sickness of my friends with whom I was to come, detained me.”

“I had no doubt there was a sufficient reason,” Miss Ashton answered kindly. “You are a week behind most of the others, but you can make the time up with diligence. Dorothy, please take Marion to the guest-room for to-night. I will see you later. I am very glad you are here safely. You will have time after tea to write a few lines home. Give my love to your mother, please.”

Dorothy led the way to the guest-room. It was a pretty room near Miss Ashton’s, kept for the convenience of entertaining guests. Dorothy threw open the window-blinds, and Marion saw before her a New England village. 12

In the near distance rose hill upon hill, their sides covered with elegant residences, and what she thought were palaces, crowning their tops. The light of this September twilight covered them with a mantle of gold, lit up the broad river that ran at the base of the hills like a translucent band, turned the tall chimneys of factories in the adjacent city, usually so disfiguring, into minarets, blazing with rich Oriental coloring.

“Is it not beautiful?” Dorothy asked, slipping her arm around Marion’s waist, and drawing her nearer the window; “we have it always—always to look at, morning, noon, and night, and it is never the same twice. I was born and brought up by the sea, and I’ve been here three years, yet I love it better and better every day.”

“I was born and brought up on the prairies.”

“The land seas,” added Dorothy. “How strange they must be! I would like to see the prairies.

“The grand thing about this is, it belongs to you all the time you stay here, just as much as if you really owned it; nobody can take it from you; there it is, and there it must remain. That is the reason they built our academy on this high hill, so it should be ours, a part of our education,—‘Grow into us,’ Miss Ashton says, and it does.”

While they stood looking at it the twilight deepened; the golden flush faded away. Over hill and river crept the shadows of the night, and out from the adjoining corridor sounded a loud gong, the first 13 one Marion had ever heard. She turned a frightened face toward Dorothy, who said, “Our gong; study hours begin now, so I must go: I shall see you to-morrow.” Then she hurried away, and Marion was left alone; but she had hardly gone, before there was a gentle tap upon her door, then it opened, and Miss Benton, one of the teachers, came in.

“What, all alone in the dark! That’s lonely for a new pupil. Let me light your gas, and then I will take you down to tea; you must be very hungry.”

Her voice was kind, and her manner gentle. She lighted the gas, then slipped Marion’s arm into hers, and took her through the long, bright corridors to the dining-hall. Here, a pleasant-faced matron came to meet her. She gave her a seat at a table, which she told her would be hers permanently, then seated herself by Marion’s side and talked to her cheerfully as she ate. It was all so homelike; every one she had met was kind and friendly. It would be her own fault certainly if she were not contented and happy here, Marion thought.

Tea over, she tried to find her way alone back to her room, but there were corridors leading to stairs, corridors leading to recitation rooms, corridors leading to a large hall dimly lighted, corridors leading everywhere but where she wanted to go, and, for a wonder, no one to be seen of whom she could ask direction. There was something so ludicrous in the situation, that every now and then Marion burst into a merry little laugh; and after a time one of her 14 laughs was echoed, and, turning, she saw a short, fat little woman with very light hair, and light blue eyes, who came directly to her, holding up two small hands and laughing.

“You, new der Mundel,” she said; “Two Hundert they call you. What for you hier?”

“I’ve lost my way. I can’t find my room,” said Marion, still laughing.

“What der Raum?”

Marion was startled. Was this an insane woman who was walking at large in the corridors? What sort of a jargon was this she was talking to her?

Had it been wholly German, or even correct German, Marion would have understood her, at least in part; but this language, what was it? The speaker, much to the amusement of the whole school, used a curious medley of neither English nor German in her attempt to speak the English, seeming to forget the proper use of her own language.

Marion answered her now with a half-frightened, “Ma’am?”

“You not stand under me? I am your teacher, German. I am Fräulein Sausmann. Berlin I vas born. I teach you der German. Come, tell me, Two Hundert, vere vas your der Raum, vat you call it? Your apartament, vere you seep?” shutting up her small eyes tight, and leaning her head on one hand, to represent a pillow.

“The guest-room,” said Marion, now understanding her. 15

“Der guest-room? Oui, oui, Madamoselle. I chapperon you,—come!”

Seizing one of Marion’s hands, she led her to her room, opening the door, then, standing on the tips of her small feet and kissing her on both cheeks, she said in English, “Good-night,” kissed her own hand, and, throwing the kiss toward Marion, disappeared.

Marion found her trunk in her room unstrapped, and, tired as she was, began to make preparations for spending the night there.

She did not suppose for a moment it was to be permanently hers, but fell asleep wondering what could be next in waiting for her.

When Dorothy left Marion at the call of the gong for study hours she went at once to her own room.

She had two room-mates, both her cousins; one, Gladys Philbrick, was a Florida girl, the only child of a wealthy owner of several orange-groves. She was motherless, and needed a woman’s care, and the advantages of a Northern education, so her father sent her to live with relatives in the small seaport town of Rock Cove.

The other, Susan Downer, was the child of a sister of Mr. Philbrick; her father followed the sea, and her brother, almost the one boy in Rock Cove who did not look upon a sailor life as the only one worth living, was at the present time a student at the academy at Atherton, only a few miles from Montrose. Dorothy herself was the child of a fisherman—her own mother dead, and she left under the care of a weak stepmother, whose numerous family of small children had made Dorothy’s life one of constant hardship.

When Mr. Philbrick, in one of his visits to Gladys at the North, became acquainted with this little 17 group of cousins, he had no hesitation—being not only an educated man, but also one of a great heart and generous nature—in making plans for their future education. In carrying these out, he had sent Jerry Downer to Atherton; Gladys, Susan, and Dorothy to Montrose.

Her cousins were already busy with their books when Dorothy came into the room; and, careful not to disturb them, she sat quietly down to study her own lessons, but she could not fix her mind upon them. Marion alone down-stairs, homesick, with no one to say a kind word to her, or to tell her about the school, “a stranger in a strange land,” she kept repeating to herself; “and such a sweet-looking girl. It’s too bad!”

Try her best not to, she still found herself watching the hands of the clock. For a wonder she was anxious to have study hours over; she wanted to tell her cousins about Marion.

As it proved, they were quite as anxious to hear; for no sooner had the clock struck nine, and the gong struck again for the close, as it had for the opening of study hours, than they shut their books, and Gladys said,—

“Tell us about Two Hundred? What a way you have, Dorothy, of always finding out people who want you!”

“She was all alone,” said Dorothy, by way of answer; “and she looked so lonely.”

“Tell us about her,” said Susan. “Never mind 18 the lonely; new scholars always are; that’s a part of their education, Miss Ashton says. We should have been if we hadn’t been all together. What is she like?”

“She’s lovely,” said Dorothy. “She is pretty, and she isn’t. Her hair just waves all over her head; and her eyes were blue, and they were hazel, and they were—”

“Gray!” put in Gladys.

“Yes, I suppose they were gray; but they were all colors, but cat colors, until it grew too dark for me to see her.”

“We shall like her. I wish she could have a room near us. Her eyes tell true tales.”

“She can,” said Gladys instantly. “She can room with me. I am the only girl in school who hasn’t a room-mate. You wait”—and Gladys, without another word, hurried out of the room. She very well knew that after nine Miss Ashton disliked a call unless there was some imperative necessity for it, so she knocked so gently on the closed door that she was hardly heard; and when at last Miss Ashton appeared, she looked so tired, and her smile was so wan, that Gladys, eager as she was, wished she had been more thoughtful; but, in her impulsive way, she blundered out,—

“She can come to me. I’m all alone, you know.”

“Who can come to you, Gladys?” If it had been any other of her pupils, Miss Ashton would have been surprised; but three years had taught her that this Florida girl was exceptional. 19

“Two Hundred! Dorothy says she is lovely, with big eyes, and lonely”—

“You mean Marion Parke?”

“Yes, that’s her name. We all call her Two Hundred.”

“Then you must not call her so any more. It would annoy her.”

“I never will if you’ll please let her come and room with me. It’s such a cheerful room, and I’ll be ever so nice to her, Miss Ashton; try me, and see.”

“But, Gladys, you know your father pays me an extra price for your having your room to yourself.”

“I think, Miss Ashton,”—looking earnestly in Miss Ashton’s face,—“he would be ashamed of me if I wasn’t willing to share it with her. Please! I’ll be as amiable as an angel.”

Miss Ashton knew the cousins well. She knew, if she excepted Susan, of whom she felt always in doubt, she could hardly have chosen out of her school any girls from whom she would have expected kinder and safer treatment for the new-comer. “How could I have doubted God would provide for this missionary child!” she thought, as she looked down into the earnest face beside her; but she only said,—

“Thank you, Gladys; I will think it over!” and Gladys, not at all sure her offer would be accepted, went back to her room.

The next morning, it must be confessed, things looked differently to her from what they had on the previous night. It was such a luxury to have a 20 whole room to herself; to throw her things about “only a little,” but that little enough to make it look untidy. She did not exactly wish she had waited until she knew more of Marion, and she tried to excuse her reluctance to herself by the doubt whether she ought not to have consulted her cousins, as their parlor was a room common to them all; but it was too late now, and when she received a little note from Miss Ashton, saying she should send Marion to her directly after breakfast, she made hasty preparations for her reception.

The dining-hall was filled with small tables, around which the girls had taken their seats, when Miss Benton came in with Marion. Generally a new-comer was hardly noticed among so many; but the peculiarity of Marion’s admittance, rounding their number to the largest the school had ever held, made her a marked character for the time. Every eye was turned upon her as she, wholly unconscious of the attention she attracted, walked quietly behind the teacher to a seat next to Gladys.

“Gladys, this is your new room-mate,” said Miss Benton. Then she introduced her to the others at the table, and left her.

“Grace before meat,” whispered Gladys to her as the customary signal for asking a blessing was given. Miss Ashton rose, and every head in the crowded hall was reverently bowed as she prayed.

They were the first words of prayer Marion had heard since she knelt by her father’s side in the far-away 21 home on the morning of her departure. “The same God here as there!” Among this crowd of strangers this thought came to her with the comfort its realization everywhere, and at all times, brings. Even here, she was not alone.

There was a low-toned, pleasant hum of conversation at the table during breakfast; the teacher who presided drew Marion skilfully into it now and then; and she was the centre of a little group as the school went from the hall to the chapel, where a short religious service was every morning conducted.

This was under Miss Ashton’s special care, and she took great pains to make it the keynote of the school-life for the day. So far in the term, what she said had its bearing on the immediate duties before them; but this morning she had felt the need of meeting the cases of homesickness with which the opening of every new year abounded, and which seemed, to the pupils at least, matters of the greatest and saddest importance.

She chose one of the most cheerful hymns in the collection they used, by which to bring the tone of the school into harmony with her remarks; and, after it was sung, she said:—

“If I were to ask, which I am too wise to do,”—here a smile broke out over the faces of her audience—“those among you who are homesick to rise, how many do you suppose I should see upon their feet?”

A laugh now, and a good deal of elbow-nudging among the girls.

“In the twenty years I have been principal of this academy, I have seen a great deal of this sickness, and I have sympathy with, and pity for it. It has been often told us that the Swiss, away from their Alpine homes, often die of it, but I have never yet found a case that was in the least danger of becoming fatal; so far from it, I might say, that when, since the Comforter sent to us in all our troubles has taken the sickness under his healing care, my most homesick pupils have become my happiest and most contented; so, if I do not seem to suffer with you, my suffering pupils, it is because I have no fear of the result.

“I have a prescription to offer you this morning. Love your home—the more the better; but keep a 23 great place in your hearts for your studies. Give us good recitations in the place of tears. Study—study cheerfully, earnestly, faithfully, and if this fails to cure you, come and tell me. I shall see I have made a wrong diagnosis of your condition.”

Another laugh over the room, in which some of the unhappy ones were seen to join.

“A few words more. I take it for granted that when a young girl comes to join my school, she comes as a lady. There are qualifications needed to establish one’s claim to the title. I shall state them briefly:—

“Kindness to, and thoughtfulness of, others; politeness, even in trifles; courtesy that wins hearts, generosity that makes friends, unselfishness that loves another better than one’s self, integrity that commands confidence, neatness which attracts; tastefulness, a true woman’s strength; good manners, without which all my list of virtues is in vain; cleanliness next to godliness; and, above all, true godliness that makes the noblest type of woman,—a Christian lady.”

Then she offered a short, fervent prayer, and the school filed out quietly to the different class-rooms for their morning recitations.

She spoke to Marion as she passed her, and Marion knew that the dreaded hour of her examination had come. She followed Miss Ashton to a room set apart for such purposes; and, to her surprise, the first words the principal said to her were,—

“Come and sit down by me, Marion, and tell me all about your home!” 24

“About home!” Marion’s heart was very tender this morning, and when she raised her eyes to Miss Ashton, they were full of tears.

“I want to learn more of your mother,”—no notice was taken of the tears. “I had such a nice letter from her about your coming, so nice that, though I hadn’t even a corner to put you in, I could not resist receiving you; and now you are invited to come into the very rooms where I should have been most satisfied to put you. I will tell you about your future room-mates; I think you will be happy there.”

Then she told her of the three cousins, dwelling upon their characters generally, leaving Marion to form her particular opinion as she became acquainted with them.

What the examination was Marion never could recall. Her father was a college graduate. Her mother had been educated at one of our best New England schools, and her own education had been given her with much care by them both.

Miss Ashton found her, with the exception of mathematics, easily prepared to enter her middle class; and the mathematics she had no doubt she could make up.

Probably there was not a happier girl among the whole two hundred than Marion when, with a few kind, personal words, Miss Ashton dismissed her. Her past studies approved, and her future so delightfully planned for. 25

Miss Ashton gave her the number of her room in the third corridor, telling her that the same young lady she had seen on the previous night was waiting to receive her.

When, after some difficulty, she found her way there, the door was opened by Dorothy, who had been watching for her.

“This is our all-together parlor,” she said. “Gladys, you know, and Susan,—this is my cousin, Susan Downer. We are glad to have you with us.”

It was a simple welcome, but it was hearty, and we all know how much that means.

Gladys led her to the window. “Come here first,” she said, “and look out.”

It was the same view she had seen from the guest-room the night before, only now it was soft and tender in the light of a half-clouded autumn sun.

“My father said, when he saw it, it ought to make us better, nobler, and happier to have this to look at. That was asking a great deal, was not it? because, you see, we get used to it. But there’s the sea; you know how the sea looks, never the same twice; because it’s still and full of ripples to-day, you don’t know but the waves will be tumbling over Judith’s Woe to-morrow.”

“I never saw the ocean,” said Marion. “That is one of the great things I have come to the East to see.”

“Never saw the ocean?” repeated Gladys, looking at Marion as curiously as if she had told her she 26 never saw the sun. “Oh, what a treat you have before you! I almost envy you. This is well enough for a landscape, but the seascapes leave you nothing to desire. Now, come to our room. You are to chum with me, and we will be awful good and kind to each other, won’t we?”

“How happy I shall be here!” was Marion’s answer, as she looked around the rooms. “I wish my mother could see it all!”

“I wish she could,” said Dorothy kindly.

The rooms in this academy building were planned in suites,—a parlor, with two bedrooms opening from it. These accommodated four pupils, unless, as was frequently the case, some parents wished their daughter—as did Gladys’s father—to have her sleeping-room to herself. In this case extra payment was made.

Marion found her trunk already in Gladys’s room, and the work of settling down was quickly and pleasantly done, with the help of her three schoolmates. Lucky Marion! She had certainly, so far, begun her Eastern life under the pleasantest auspices.

And now commenced Marion’s work. She was not quite fitted in higher mathematics, and Miss Palmer, not disposed to be too indulgent in a study where stupid girls tried her patience to its utmost every day of her life, conditioned her without hesitation.

Miss Jones found her fully up, even before her class, in Latin and Greek; her father having taken special pains in this part of her education, being himself one of the elect in classical studies when in Yale College. Her words of commendation almost made amends to Marion for Miss Palmer’s brief dismissal; almost, not quite, for, in common with nine-tenths of the scholars in the academy, Marion “hated mathematics.”

Miss Sausmann tried her on the pronunciation of a few German gutturals, then patted her on the shoulder and said,—

“Marrione, you vill do vell; you may koom: I vill be most gladness to ’ave you koom. I vill give unto you one, two, three private lessons. You may koom to-day, at four. The stupid class vill not smile at 28 you; you vill make no mistakens.” Then she kissed Marion as affectionately as if she had been a dear old friend, and watched her as she went down the long corridor. Some words she said to herself in German, smiled pleasantly, waved two little hands after the retreating figure, and smiled again, this time with some self-congratulatory shakes of the head.

The truth was, though German was an elective study, it was by no means a favorite in the school, and, it may be, Miss Sausmann was not a popular teacher. Broken English, too great an affection for, and estimation of the grandeur of, the Fatherland, joined with a quick temper, do not always make a successful teacher.

The girls, moreover, had fallen rather into the habit of making fun of her, and this did not add to her happiness. In Marion she thought she saw a friend, and very welcome she was.

The arrangement that put four scholars in one room for study, also was not the wisest on the part of the architect of Montrose Academy. If he had taught school for even one year, he would have found how easy it was for a restless scholar to destroy the quiet so essential to all true work.

In Marion’s room there was not a stupid or a lazy girl; but they committed their lessons at such different times, and in such different ways, that they often proved the greatest annoyance to each other.

One of the first obstacles Marion found as she bent 29 herself to real hard work, was the need of a place where her attention was not continually called from her book to something one of her room-mates was doing or saying.

To be sure, it was one of the rules of the school that there should be perfect quiet in the room during study hours, but that was absolutely impossible; and Marion, especially with her mathematics, found herself struggling to keep her thoughts upon her lesson, until she grew so nervous that she could not tell x from y, or demonstrate the most common proposition in an intelligible way; and now she found to her surprise a new life-lesson waiting for her to learn, one not in books. So far, her life had all been made easy and sure by the wise parents who had never allowed anything to interfere with their child’s best interests; as they had made more and greater sacrifices than she ever knew, to send her East for her education, so nothing that could prepare her for it had been forgotten or neglected.

The very opportunities she had craved had been granted her, and she found herself hindered by such trifles as Gladys moving restlessly around the room, her own lessons well learned, lifting up a window curtain and letting a glare of sunshine fall over her book, knocking the corner of the study table, pushing a chair; no matter how trifling the disturbance, it meant a distracted attention, and lost time; or, Susan would fidget in her chair, draw long and loud breaths, push away one book noisily and take up 30 another, fix her eyes steadily on Marion, look as if she were watching the slow progress she made, and wondering at it.

Even Dorothy, dear, good Dorothy, was not without her share in the annoyance. If she had any occasion to move about the room, “she creeps as if she knew how it troubles me, and was ashamed of me,” thought nervous Marion.

In her weekly letters home she gave to her mother an exact account of her daily life, and among the hindrances she found this nervous susceptibility was not omitted. It had never occurred to her that it was a thing under her own control, therefore she was not a little surprised when she received the following letter from her mother:—

“My Dear Child,—You are not starting right. What your room-mates do, or do not do, is none of your concern. Learn at once what I hoped you had learned, at least in part, before leaving home, to fix your mind upon your lesson, to the shutting out of all else while that is being learned. I know how difficult this will seem to you, with your attention distracted by everything so new about you; but it can be done, and it must be if you are to acquire in the only way that will be of any true use to you in the future. Remember that the very first thing you are to do, in truth the end and aim of all education, is to develop and strengthen the powers of your mind. Acquisition is, I had almost written, only useful in so far as it tends to this great result. When you leave school, if your memory is stored with all the facts which the curriculum of your school affords, and you lack in the mental control which makes them at your service, your education has only made your mind a lumber-room, full perhaps to overflowing, but useless for the great needs of life. Now you will wonder what all this has to do with your being made uncomfortable, so that you could not study, by the restlessness of your room-mates. If you begin at once 31 to fix your mind, as I hope you will soon be able to do, on your lesson, you will be delighted to find how little you will be disturbed by anything going on around you, and how soon your ability to concentrate your working powers will increase.

“Try it faithfully, my dear one, and write me the result. I want to send you one other help, which I am sure you will enjoy. In your studies, make for yourself as much variety as possible. By that, I mean when you are tired of your Latin do not take up your Greek; take your mathematics, or your logic, or your literature,—any study that will give you an entire change. Change is rest; and this is truer even in mental work than in physical. Above all, do not worry. Nothing deteriorates the mind like this useless worry. When you have done your best over a lesson, do not weary and weaken yourself by fears of failure in your recitation room. Nothing will insure this failure so certainly as to expect it. Cultivate the feeling that your teacher is your friend, and more ready to help you, if you falter, than to blame you. You think Miss Palmer is hard on you in your mathematics, and don’t like you. Avoid personalities. At present, you probably annoy Miss Palmer by your blunders; but that is class work, and I do not doubt a little sharpness on her part is good for you; but, out of the recitation room, you are only ‘one of the girls,’ and if you come in contact with her, I have no doubt you will find her an agreeable lady. There is a tinge of self-consciousness about this, which I am most anxious for you to avoid. I want you to forget there is such a person in the world as Marion Parke, in your school intercourse; but more of this at another time.”

Here follows a few pages written of the home-life, which Marion reads with great tears in her eyes.

What her mother has written her Marion had heard many times before leaving home, but its practical application now made it seem a different thing. She could not help the thought that if her mother had been in her place, had been surrounded as she was by the new life,—the teachers, the 32 scholars, the routine of everyday,—if she had seen the anxious, pale faces of many of the girls when they came into the recitation room, and the tears that were often furtively wiped away after a failure, she would not have thought it so easy to fix your attention on your lesson, undisturbed by any external thing, or to bend your efforts to the development of your mind, above every other purpose: but, after all, the letter was not without its salutary effect; and coming as it did at the beginning of Marion’s school career, will prove of great benefit to her.

The trustees of Montrose Academy had not only chosen a fine site upon which to erect the building, but they had also very wisely bought twenty acres of adjacent land, and laid it out in pretty landscape gardening. There was a grove of fine old trees, that they trimmed and made winding paths where the shade was the deepest and the boughs interlaced their arms most gracefully. They cut a narrow driveway, which proved so inviting that, after a short time, there had to appear the inevitable placard, “Trespassing forbidden.” A small brook made its way surging down to the broad river that flowed through the town; this they caused to be dammed, and in a short time they had a pond, over which they built fanciful bridges. The pond was large enough for boats; and these, decked with the school color,—a dainty blue,—were always filled with pretty girls, who handled the light oars, if not with skill, at least with grace, and, as Miss Ashton knew, with perfect safety.

During the fine days of the matchless September weather, this grove was the favorite resort of the 34 girls through the hours allotted to exercise; and here Marion, having found a quiet, shaded nook where she could be sure of being alone, brought her book and did some of her best studying.

“It’s easy enough,” she thought with much self-gratulation, “to fix your mind on what you are doing, with nothing to disturb you; but it’s a different thing when there are three other minds that won’t fix at the same time. I just wish mother would try it.”

One day, however, when her satisfaction was the most complete over an easily mastered Latin lesson, a laughing face peeped down upon her through her canopy of green leaves, and a voice said,—

“Caught you, Marion Parke! Now I’m going straight in to report you to Miss Ashton, and you’ll see what you’ll get.”

“What shall I?” asked Marion, laughing back.

“She’ll ask you very politely to take a seat by her on the sofa, and then she’ll look straight in your eyes and she’ll say,—

“‘I am very sorry, Marion, to find you so soon after joining my school breaking one of my most important regulations.’ (She always says regulations; we don’t have any rules here.) ‘I had expected better things of you, as you are a minister’s daughter, and came from the far West.’”

“Is studying your lesson, then, breaking a rule?”

“Studying it in exercise hours is an unpardonable sin. Don’t you know we are sent out into the open air for rest, change, exercise? You ought to be rowing, 35 walking, playing croquet, tennis, base-ball, football. You’ve to recruit your shattered energies, instead of winding them up to the highest pitch. We’ve been watching you, but no one liked to tell you, so I came. I won’t tell Miss Ashton this time, if you’ll promise me solemnly you’ll join our croquet party, and always play on our side! Come; we’re waiting for you!”

“Wait until I come back,” said Marion, rising hastily, and gathering up her books. “I didn’t know there was any such a rule—regulation, I mean.”

Then, half frightened and half amused, she went back to the house, straight to Miss Ashton’s room.

Miss Ashton was busy, but she met her with a smile.

“Miss Ashton,” said Marion, “I am very sorry; I didn’t know it was against your wishes. I found such a lovely, quiet little nook in the grove, and I’ve been studying there when Mamie Smythe says I ought to have been exercising.”

“Then you have done wrong,” said Miss Ashton gravely. “I understand that the newness of your work makes your lessons difficult, but there is nothing to be gained by overwork. Come to me at some other time, and I will talk with you more about it. Now go, for the pleasantest thing you can find to do in the way of healthful exercise. There are some fine roses in blossom on the lawn; I wish you would pick me a nice, large bunch for my vase. Look at the poor thing! See how drooping the flowers are!” 36

Mamie Smythe’s croquet party waited in vain for Marion’s return; but on the beautiful lawn, where the late roses were doing their best to prolong their summer beauty, Marion went from bush to bush, picking the fairest, and conning a lesson which somehow seemed to her to be a postscript to her mother’s letter, that was, “Study wisely done was the only true study.”

The lawn itself, cultured and tasteful, had its share, and by no means a small one, in the work of education. Clusters of ornamental trees, dotted here and there over its soft green, were interspersed with lovely flower-beds, in which were growing not only rare flowers, but the dear old blossoms,—candytuft, narcissus, clove-pinks, jonquils, heart’s-ease, daffodils, and many another to which the eyes of some of the young girls turned lovingly, for they knew they were blossoming in their dear home garden.

As Marion was going to her room, after taking her roses to Miss Ashton, she found Mamie Smythe waiting for her.

“O you poor Marion!” she said, catching Marion by the arm, “I—I hope she didn’t scold you; she never does—never; but she looks so hurt. I never would have told on you, and nobody would. We all knew you didn’t know; I’m so sorry!”

“I told on myself,” said Marion, laughing, “and she punished me. Don’t you see how broken-hearted I am?”

“What did she do to you? Why, Marion Parke, 37 she is always good to those who confess and don’t wait to be found out!”

“She sent me out to pick her a lovely bunch of roses.”

“Oh!” said Mamie. Then a small crowd of girls gathered round them, Mamie telling them the story in her own peculiar way, much to their amusement; for Mamie was the baby and the wit of the school, a spoiled child at home, a generous, merry favorite at school, a good scholar when she chose to be, but fonder of fun and mischief than of her books, consequently a trouble to her teachers. She was a classmate of Marion, and for some unaccountable reason, as no two could have been more unlike, had taken a great fancy to her, one of those fancies which are apt to abound in any gathering of young girls. Had Marion returned it with equal ardor, the two, even short as the term had been, would be now inseparable; but Marion had her room-mates for company when her lessons left her any time, and Gladys and Dorothy had already learned to love her. As for Susan, she seemed of little account in their room. She would have said of herself that she “moved in a very different circle,” and that was true; even a boarding-school has its cliques, and to one of the largest of these Susan prided herself upon belonging. Just what it consisted of it would be difficult to say, certainly not of the best scholars, for then both Gladys and Dorothy would have been there; not of the wealthiest girls, for then, again, Gladys Philbrick 38 was one of the richest girls in the school; not of the most mischievous, or of idlers, for then Miss Ashton would have found some way of separating them; yet there it was, certain girls clubbing together at all hours and in all places, where any intercourse was allowed, to the exclusion of others: walking together, having spreads in each other’s rooms, going to concerts, to meetings, anywhere and everywhere, always together.

Miss Ashton, in her twenty years of experience had seen a great deal of this; but she had learned that the best way of dealing with it was to be ignorant of it, unless it interfered in some way with the regular duties of the school. This it had only done occasionally, and then had met with prompt discipline. As several of the leaders had graduated the last Commencement, she had hoped, as she had done many times before, only to be disappointed, that the new year would see less of it; but it had seemed to her already to have assumed more importance than ever, so early in the fall term.

She very soon saw Mamie Smythe’s devotion to Marion, and knowing how fascinating the girl could make herself when she wished, and how genial was Marion’s great Western heart, she expected she would be drawn into the clique. On some accounts she wished she might be, for she had already begun to feel that where Marion was, there would be law and order; but, on the whole, she was pleased to see that her new pupil, while she was rapidly making 39 her way into that most difficult of all positions in a school to fill, that of general favorite, was doing so without choosing any girl for her bosom friend.

“She helps me,” Miss Ashton thought with much self-gratulation, “for she is not only a winsome, merry girl, but a fine scholar, and already her Christian influence begins to tell.”

In the prospectus of Montrose Academy was the following sentence:—

“The design of Montrose Academy is the nurture of Christian women.

“To this great object they dedicate the choicest instruction, the noblest personal influences, and the refinements of a cultivated home.”

It was to carry out this, that religious instruction was made prominent.

Not only was the Bible a weekly text-book for careful and critical study, but, in accordance with an established custom of the school, among the distinguished men and women who nearly every week gave lectures or addresses to the young ladies, were to be found those who told them of the religious movements and interests of the day. Not only those of our own country, but those of a broader field, covering all the known world.

Returned missionaries, with their pathetic stories of their past life.

Heads of the great philanthropic societies, each 41 one with its claim of special and immediate importance.

Professors for theological seminaries and from prominent colleges, discussing the prevailing questions that were agitating the public mind.

Trained scholars in the scientific world, laden with their rich treasures of research into nature’s hidden secrets.

Musicians of wide repute, who found an inspiration in the glowing young faces before them, that called from them their choicest and their best.

Elocutionists, with their pathetic and humorous readings, always finding a ready response in their delighted audience.

These, and many others of notoriety, were brought to the academy; for Miss Ashton had not been slow in learning what is so valuable in modern teaching,—variety.

If there were fewer prayer-meetings in the corridors among pupils and teachers than in olden times, there was in the school more alertness of mind, a steadier, stronger ability to think, and, consequently, to study, and, therefore, judiciously used, more power to grasp, believe in, and love the great Christianity to whose service the academy was dedicated.

Nor was it by these lectures alone that the educational advantages were broadened.

The library every year received often large and important additions. It would have been curious to note the difference between the literature selected 42 now, and that chosen years ago. Then a work of fiction would have been considered entirely out of place on the shelves of a library consecrated to religious training. Now the pupils had free access to the best works of the best literary authors of the day, in fiction or otherwise. Monthly magazines and newspapers were spread upon the library table. There was but one thing required, that no book taken out should be injured, and that no reading should interfere with the committal of the lessons.

In the art gallery the same growth was readily to be seen. The portraits of the early missionaries who had gone out from the school, and whose names had become sainted in the religious world, still hung there; but the walls were covered now with choice paintings,—donations from the rapidly increasing alumnæ, and from friends of the school. Here the art scholars found much to interest and instruct them, not only in the pictures, but in the models and designs, which had been selected with both taste and skill.

There was a cabinet of minerals; but this was by no means a favorite with the pupils, though here and there a diligent student might be seen possibly reading “sermons in the stones,” who could tell!

There seemed, indeed, nothing to be wanting for the “higher education” for which the institution was designed, but that the pupils should accept and improve the privileges offered them.

Marion Parke was not the only one who found herself 43 confused by the sudden wealth of opportunity surrounding her. Other pupils had come from the north and the south, the east and the west, many from homes where few, if any, of the advantages of modern life had been known. That Marion should have appreciated, and to some extent have appropriated, them as readily as she did, is a matter of surprise, unless her educated Eastern parents are remembered, also the amenities of her parsonage home. Certain it is, that watching her as so many did, and as is the common fate of every new pupil, there was not detected any of the “verdancy” which so often stamps and injures the young girl. It was the girl next to her who leaned both elbows on the table, and put her food into a capacious mouth on the blade of her knife.

It was the one nearly opposite her that talked with her mouth so full she had difficulty in making herself understood; and another, half-way up the table, to whom Miss Barton, the teacher who presided, had occasion to say, when the girl, having handled several pieces of cake in the cake-basket, chose the largest and the best,—

“Whatever we touch here, Maria, we take.”

A hard thing for Miss Barton to say, and for the girl to hear; but it must be remembered that this is a training as well as a finishing school, and that there is an old adage with much truth in it, that “manners make the man.”

It may seem a thing almost unnecessary and 44 unkind to suggest, that even the most brilliant scholarship could not give a girl a high standing in a school of this kind, if it were unaccompanied with the thousand little marks of conduct which attest the lady.

Maria, after her rebuke from Miss Barton, left the table in a noisy flood of tears, of course the sympathy of all the girls going with her. Miss Barton was pale, and there were tears in her eyes; but no one noticed her, unless it was to throw toward her disapproving looks.

The fact was, that she had spoken to Maria again and again, kindly and in private, about this same piece of ill-manners, and the girl had paid no heed to it. There seemed nothing to be left to her but the public rebuke, which, wounding, might cure.

Marion took the whole in wonderingly. Was this, then, considered a part of that education for which purpose what seemed to her such a wealth of treasures had been gathered?

Here were lectures, libraries, art galleries, beautiful grounds, excellent teachers, a bevy of happy companions, and yet among them so small a thing as a girl’s handling cake at the table, and choosing the largest and the best piece, was made a matter of comment and reproof, and, for the first time since she had been in the academy, had raised a little storm of rebellion on the part of pupils towards a teacher.

When she went to her room, Susan had already 45 told the others, who sat at different tables, what had happened. Susan was excited and angry, but Dorothy said quietly,—

“And why should Maria have taken the best bit of cake, even if it had been on the top? I wouldn’t.”

“No: you would have been the last girl in the school to take the best of anything,” said Gladys, giving Dorothy a hug and a kiss; “and as for Miss Barton, she’s a dear, anyway, and I dare say she feels at this moment twice as bad as Maria.”

“Sensible girl, am I not, Marion?” seeing Marion come into the room. “Don’t you take sides in any such things; you mind what I say! Teachers know what they are doing; and if any of us are reproved, why, the long and short of it is, nine times out of ten we deserve it. It’s ‘for the improvement of our characters’ that everything is done here.”

“I believe you,” said Marion heartily; and, trifling as the event was, she put it with the long array of educational advantages which she had come from the far West to seek. “It requires attention to little as well as great things”—she thought, wisely for a girl of sixteen—“to accomplish the object of this finishing-school.”

“Well! what of that! If college boys can have secret societies, and the Faculties, to say the least, wink at them, why can’t academy girls? I don’t see!”

This is what Jenny Barton said one evening to a group of girls out in the pretty grove back of the academy building.

There were six of them there. Jenny had culled them from the school, as best fitted for her purpose. She had two brothers in Harvard College, and she had been captivated by their stories of the “Hasty Pudding Club,” of which they were both members. “So much fun! such a jolly good time! why not, then, for girls, as well as for boys?”

When, after the long summer vacation, Jenny came back to school to establish one of these societies, to be called in after years its founder, and at the present time to be its head, this was the height of her ambition, the one thing that she determined to accomplish. These six girls that in the gloaming of this September night are waiting to hear what she has to say were well chosen. There 47 was Lucy Snow, the one great mischief-maker in the school. No teacher but wished her out of her corridor; in truth, no teacher, not even Miss Ashton, who never shrank from the task of trying to make over spoiled pupils, was glad to see her back at the beginning of a new year. There was Kate Underwood, a brilliant girl, a fine scholar, and the best writer in the school. There was Martha Dodd, whose parents were missionaries at Otaheite; but Martha will never put her foot on missionary ground. There was Sophy Kane, who held her head very high because she was second cousin of Kane, the Arctic explorer, and who talked in a grand manner of what she intended to do in her future. There was Mamie Smythe, “chock-full of fun,” the girls said, and was never afraid, teachers or no teachers, rules or no rules, of carrying it out. There was Lilly White, red as a peony, large as a travelling giantess, with hands that had to have gloves made specially to fit them, and feet that couldn’t hide themselves even in a number ten boot. She was as good-natured as she was uncouth, and never happier than when she was being made a butt of. These were to be the nucleus around which this society was to be formed; and as they threw themselves down on the bed of pine-leaves which carpeted the old stump of a tree upon which Jenny Barton was seated, they were the most characteristic group that could have been chosen out of the school. Jenny had shown her powers of leadership when she made the selection. 48

The opening sentence of this chapter was what she said in reply to some objection which Kate Underwood had offered. Kate liked to be popular, to be admired and courted for her talents: it was the secret society that would prevent this. This, Jenny Barton understood; and in the long debate that followed she met it well.

There should be a public occasion now and then. Did not the Harvard societies give splendid spreads, and have an abundance of good times generally?

The society was established, and its name, after a long and warm debate, chosen: “The Demosthenic Club.” “For we are going to debate, you know; train for lecturers, public readers, ministers, actresses, lawyers, and whatever needs public speaking,” said President Jenny. Vice-President Kate Underwood gave her head an expressive toss, and, if it hadn’t been too dark to see her smile, there might have been seen something more than the toss; for while they talked, the long twilight had faded away, the little ripples of the lake by whose side they were sitting had gone to sleep on its quiet bosom. The air was full of the chirrup of innumerable insects; two frogs, creeping up from the water, adding a sonorous bass, and the long, slender pine-leaves chimed into this evening lullaby with their sad, sweet, Æolian notes.

But little of all of this did this Demosthenic Club notice as, coming out at length from the darkness of the grove, they saw the sky full of stars, the academy 49 windows blazing with gas-light, and knew study hours had been begun.

Not to be in their rooms punctually at that hour was an infringement upon the “regulations” not easily excused, and to begin the formation of their society by incurring the displeasure of their teachers did not promise well for their future.

“Take off your boots,” whispered Mamie Smythe, as they stood hesitating at the door. In a moment every pair of boots was in the girls’ hands, and they were creeping softly through the empty corridors toward their respective rooms. As fate would have it, the only one who reached her room was Lilly White. To be sure, Fräulein Sausmann, the German teacher, heard steps in her corridor, and, opening her door a crack, peeped out. When she saw Lilly White creeping along on the toes of her great feet, her boots, like two boats, held one in each hand, she only smiled, and said to herself, “Oh, Fräulein White! She matters not. She studies no times at all,” and shut her door.

All the others were taken in the very act; and their shoeless feet, their confession of a guilty conscience, were reported to Miss Ashton.

“Seven of the girls! that means a conspiracy of some sort,” said this wise teacher. “I must keep an eye upon them.”

How much any one of this “Demosthenic Club” suspected of their detection by their corridor teachers it would be difficult to say, for, except by a glance, 50 no notice was taken of them at the time. Jenny Barton told the others triumphantly at their next secret session, how she had hidden her shoes behind her, and taken little, mincing steps, so to hide her feet, and imitated the whole performance, much to the amusement of the others. “Ah, but!” said Mamie Smythe, “that wasn’t half as good as what I did. When I met Miss Stearns pat in the face, and she looked me through and through with those great goggle eyes of hers, I just said, ‘O Miss Stearns, I was so thirsty I couldn’t study; I had to go and get a drink of ice-water!’

“Then the ugly old thing stared at the boots I had forgotten to hide, as much as to say, ‘It was very necessary, in order to go over these uncarpeted floors, to take off your boots, I suppose, Mamie Smythe!’ If she had only said so right out, I should have answered,—

“‘Why, Miss Stearns, I did it so not to make a noise;’ that’s true, isn’t it, now?” looking round among the laughing girls.

“And you ought to have added,” put in Kate Underwood, “you didn’t want to disturb any one in study hours; that was true, wasn’t it?”

“Exactly what I would have said; but then, when she only goggle-eyed me, what could a girl do?”

“Do? Why, do what I did,” said Lucy Snow. “I walked right up to Miss Palmer, she’s so ill-natured, and likes so much to have us all hate her, that you can do anything with her, and I said,— 51

“‘Miss Palmer! I know it’s study hours, but I ate too much of that berry shortcake for tea, and I went to find the matron, to see if she couldn’t give me something to ease the pain.’

“‘I think’ said she (the horrid thing), ‘if you would put on your boots, it might alleviate the pain; but for fear it should not—you didn’t find the matron, I suppose?’

“‘No, ma’am,’ I said, ‘I didn’t see her; I had to come away no better than I went.’

“‘I am very sorry for you; you appear to be in great pain.’

“I was doubling up like—like a contortionist,” and she smiled, and said,—

“‘Come into my room, as you can’t find the matron, perhaps I can help you.’

“So in I had to go; and, girls, if you can believe it, after fumbling around among her phials, she brought me something in a tumbler. It was half full and looked horrid! I tell you, I shook in my stocking feet, and I began to straighten up, and whimpered,—I could have cried right out, it looked so awful, so awful, but I only whimpered,—‘I’m better, a good deal, Miss Palmer; I’ll go to my room, and if I can’t study, I’ll go to bed.’

“‘You must take this first. I don’t like to send you away in such severe pain, particularly as you couldn’t find the matron, without doing something to help you. You know I am responsible to your parents for your health!’ 52

“‘My parents never give me any medicine,’ I snarled, for I was getting ruxy by this time.

“‘Perhaps you would have enjoyed better health if they had, and would have been less liable to these sudden attacks of pain,’ she said; and, girls, if you can believe it, when I looked up in her face, there she was in a broad grin, holding the tumbler, too, close to my mouth.

“‘I’m—I’m lots better,’ I whimpered.

“‘I’m glad to hear it,’ the ugly old thing said; ‘but I must insist on your drinking this at once, or I shall have to take you down to Miss Ashton’s room; she is more responsible than I am, and I am sure would not pass any neglect on my part over.’

“By this time the tumbler touched my lips, and, girls, I was so sure that she would take me down to Miss Ashton,—and there is no such thing as keeping anything away from her, for you know how she hates what she calls a ‘prevarication,’—that I just had my choice, to drink that nasty stuff, or to betray the Demosthenic Club, or to tell a fib, and have my walking-ticket given me, so I opened my mouth wide, and swallowed one swallow, then was going to turn away my head, but Miss Palmer held the tumbler tight to my lips, as I have seen people do to children when they were giving castor oil. I took another, and tried again, but there was the tumbler tighter still, so down with it I went, and—and—she had no mercy; she made me drain it to the last drop; then she put it on the table, and said,— 53

“‘Now, Lucy, you can go to your room; I think you will feel well enough to study your lesson, but if you do not, come back in a half-hour, and I will give you another, and a stronger dose. Put on your boots before you go; you may take cold on the bare floors, in your condition. Good-night.’

“She opened her door, and held it open in the politest way until I had passed out, then I heard her laugh—laugh out loud, a real merry, ringing laugh, every note of which said as plainly as words could,—

“‘I’ve caught you now, old lady. How is the pain? Did the medicine help you?’

“I tell you, girls, it was the hardest pain I ever had in my life, and I never want another.”

“Tell us how the medicine tasted,” said Lilly White.

“Tasted! why, like rhubarb, castor oil, assafœtida, ginger, mustard, epicac, boneset, paregoric, quinine, arsenic, rough on rats, and every other hideous medicine in the pharmacopœia.”

“Good enough for you; you oughtn’t to have lied,” said Martha Dodd, her missionary blood telling for the moment.

But the other girls only laughed; the joke on Lucy was a foretaste of the fun which this club was to inaugurate.

Now, if Miss Palmer did not report to Miss Ashton, and she break up the whole thing, how splendid it would be! 54

Undaunted, as after a week nothing had been said to them in the way of disapproval, they went on to choose the other members of the club; to appoint times and places for meeting; and to organize in as methodic and high-sounding a manner as their limited experience would allow.

That the formation of such an insignificant thing as this Demosthenic Club should have affected girls like Dorothy Ottley and Marion Parke would have seemed impossible; but it was destined to in ways and times that were beyond their control. When the club was making its selection of members, among those most sought were Marion and Dorothy. Marion, with her cheery, social Western manners, made her way rapidly into one of those favoritisms which are so common in girls’ boarding-schools. She always had a pleasant word for every one, and always was ready to do a kind, generous act. She was so pretty, too, and dressed so simply and neatly, that there was nothing to find fault with, even if the girls had not been, as girls are, in truth, as a class, generous, noble, on the alert to see what is good, rather than what is otherwise, in those with whom they live. As for Dorothy, she was the model girl of the school. The teachers trusted and loved her, so did the pupils. No one among them all said how the sea had browned and almost roughened her plain face; how hard work, 56 anxiety, and poor fare had stunted her growth; how carrying the cross children, too big and too heavy, had given a stoop to her delicate shoulders, and knots on her hands, that told too plainly of burdens they were unable to lift. All that the school saw or thought of was the gentle love that was always in the large gray eyes, the kind words that the firm lips never failed to speak, and the steady, straightforward, honorable life of the best scholar.

“If we can only get those two,” said President Jenny Barton, “our club is made.”

“They are so good, they’ll spoil the fun,” said Mamie Smythe.

“For shame!” said Martha Dodd. “You don’t suppose the daughter of a missionary would join a club of which good girls could not be members!”

“Or the cousin of so famous a man as Kane, the Arctic explorer,” said Sophy Kane.

“Don’t dispute, girls; we seem to spend half our time wrangling,” and the president knocked, with what she made answer for the speaker’s gavel, noisily on the table. “I nominate our vice-president, Miss Underwood, to inform these young ladies of their having been chosen, and to report from them at our next meeting.

“Is the nomination accepted?”

“Ay! ay!” from the club.

In accordance with this request, Kate Underwood had interviewed Marion and Dorothy secretly, and had received from both a positive refusal. 57

“I have no time for secret societies,” said Dorothy with a good-natured laugh. “I want twice as many hours for my studies. Thank you, all the same, Kate.”

“Secret society! what is that?” asked Marion. “What is it secret for? What do you do in it that you don’t want to have known? I don’t like the secret part of it. My father used to tell me about the secret societies in Yale College, and they were full of boys’ scrapes. He nearly got turned out of college for his part in one of them; and if I should get turned out from here, it would break his heart. No, thank you, I’d better not.”

So, sure that no from them meant no, Kate had reported to the club, and received permission to invite Susan Downer and Gladys Philbrick in their places.

“Sue will come of course, and be glad to,” the club said. “Really, on the whole, she will be better than Dorothy, for Dorothy always wants to toe the line.”

Of Gladys, they by no means felt so sure. “She is, and she isn’t,” Lucy Snow said; “but she has lots of money, and that means splendid spreads.”

“But she won’t—she won’t”—Martha Dodd stopped.

“Won’t what?” asked the president in a most dignified manner.

“Won’t go through the corridors with her boots in her hands,” said Mamie with a rueful face, “and 58 get dosed. She’d stamp right along into Miss Ashton’s room, and say,—

“‘Miss Ashton, I’m late. Mark me, will you?’”

“She will keep us straight, then. I vote for Gladys;” and the first to hold up her hands—both of them—was Missionary Dodd.

So Gladys and Susan were invited to become members of the club, and accepted gladly, not knowing their room-mates had declined the same honor.

It was in this way that the club was to influence the rooms.

October, the regal month, when nature puts on her most precious vestments, dons her crowns of gold, clothes herself in scarlet robes, with girdles of richest browns, has a half-hushed note of sadness in the anthems she sings through the dropping leaves, listens for the farewell of departing birds, and tries in vain to call back to the browning earth the dying flowers. This month was always considered in Montrose Academy the time for settling down to hard work in earnest. Vacation, with its rest and its pleasures, seemed far behind the life of the two hundred young girls who had entered into, and been absorbed by, the present, and who were roused by ambitions for the future.

Marion’s room-mates went thoroughly into the work required of them.

“Your faithfulness during the first six weeks of the term,” Miss Ashton had said to them in one of 59 her morning talks, “will determine your standard for the year. Do not any of you think you can be indolent now, and pick up your neglected studies by and by.

“You may trust my experience when I tell you that, in the whole number of years since I have been connected with this school, I never knew a pupil who failed in her duties during the first half of the first term of the year, who afterwards did, indeed could, make up the lost opportunities.

“It is not only what you lose out of the passing recitation that you can never find again, but, of even more consequence, it is what you lose in forming honest, faithful habits of study.

“There are many different ways of studying. I have often tried to make these plain to you. I will repeat them. First, learn to give your whole attention to your lesson; fix your mind upon it. This sounds as if it would be an easy thing to do; but, in truth, it is very difficult. I am sorry to say I do not think there are a dozen girls among you who can do this successfully, even after years of training. You can train your body to accomplish wonders, but it is hard to believe that the mind is even more capable of being brought into subjection by the will than the body; and, to do that, to make your mind your servant, is to accomplish the greatest result of your education. Only as far as your study and your general life here do that, are they of any true value to you. 60

“You will ask me how are you to fix your attention when there are so many things going on around you to distract your thoughts? I can only answer, that as our minds are in many respects of different orders, so, no general rule can be given. If you will, each one, faithfully make the attempt, I have no doubt you will succeed, in just the same proportion as you are faithful.

“It may be as well, as I consider this the keystone of all good study, that I should leave the other helps and hindrances for some future talk; and it will give me a great deal of pleasure if I can hear from any of you at the end of a week’s trial, that you have found yourselves helped by my advice.”

It speaks well for Miss Ashton’s influence over her school that there was not a pupil there who was not moved by what she had said.

To be sure, its effect was not equally apparent. There were some who had scant minds to fix, and what nature had been niggardly in bestowing, they had frittered away in a trifling life; but for the earnest girls, those who truly longed to make the most of themselves and to be able to do a worthy work in the life before them, such advice became at once a help.

“It sounds like my mother’s letter to me,” Marion Parke said to Dorothy, as they went together to their room. “She insists that it is not so much the facts we learn, as the help they give us in the use of our minds. I wonder if all educated people think the same?” 61

“All thoroughly educated people I am sure do,” answered Dorothy. “Sometimes I feel as if my mind was a musical instrument; and if I didn’t know every note in it, the only sounds I should ever hear from it would be discords,”—at which rather Irish comparison, both girls laughed.

There was one peculiarity of Montrose Academy that had been slow to recommend itself to the parents of its pupils. That was the elective system, which was adopted after much controversy on the part of the Board of Trustees.

The more conservative insisted that the prosperity of the past had shown the wisdom of keeping strictly to a curriculum that did not allow individual choice of studies. The newer element in the Board were equally sure that to oblige a girl to go through a course of Latin and Greek, of higher mathematics, of logic and geology, who, on leaving school, would never have the slightest use for them, was simply a waste of time. A compromise was made at length, by which, for five years, the elective system should be practised, it being claimed that no shorter time could fairly prove its success or its failure; and during this period certain studies of the old course should be insisted upon. First and foremost the Bible, the others chosen to depend upon the class.

The year of Marion’s entering the school was the second of the experiment; and, after joining the 63 middle class and having her regular lessons assigned to her, she was not a little surprised, and in truth confused, by Miss Ashton asking her, as if it was a matter of course, “What do you intend to do in the future?” as if she expected her to have her future all mapped out, and was to begin at once her preparation for it. Miss Ashton saw her embarrassment, and helped her by saying,—

“Many of the young ladies come here with very definite plans; for instance, your room-mate Dorothy is fitting for a teacher, and a very fine one she will make! Gladys is making special study of everything pertaining to natural science,—geology, botany, physics, and chemistry. She intends when she goes back to Florida to become an agriculturist. I dare say you have already heard her talk of the wonderful possibilities to be found there. Her father is an enthusiast in the work, and she means to fit herself to be his able assistant. Susan wants to be a banker, and avails herself of every help she can find toward it.

“You see our little lame girl Helen! She is to be an artist, and devotes all her spare time to courses in art. She is in the second year, and has made wonderful progress in shading in charcoal from casts and models. She uses paints, both oils and watercolors, but those do not come in our regular course.

“If we see any special talent in a pupil in any line, we do not confine ourselves to what we can do for her, but we call in extra help from abroad.

“Kate Underwood is to be a lawyer. Mamie 64 Smythe has a new chosen profession for every new year, but as she is an only child, and her mother is wealthy, she will never enter one.

“I might go on through perhaps an eighth of the school, and point out to you girls who are studying with an aim. For the greater number, they are content to go on with the regular curriculum; as their only object, and that of their parents for them, seems to be to secure sufficient education to make them pass creditably through the common life of ordinary women.

“I thought you might have a definite object in view; and as you are now fairly started in your classes, and, as your teachers tell me, are doing very well, if you had a plan, you could find time to choose such other studies as would help you.”

This was new to Marion; she asked for time to think it over, which Miss Ashton gladly allowed her.

She had in her heart made her choice, but that, with all the other advantages offered, she could do anything except in a general way to help this choice forward, she had never dreamed. Her room-mates noticed how silent and thoughtful she was after her talk with Miss Ashton, and wondered what could be the cause, surely she was too faithful and far too good a scholar for any remissness that would have to be rebuked; but no one asked her a question.

It was after two days that Marion wrote her mother, and her letter caused a great surprise in the Western parsonage. This is in part what she wrote:— 65

“Miss Ashton has asked me what I am to do in the future. It seems they not only give you the regular curriculum, but are ready to allow you elective studies, by which you can fit yourself for your particular future.

“I wonder if you will think me a foolish girl when I write you that, if you both approve, I should like to be a doctor! Don’t laugh! I have seen so much sickness that there was no really educated physician to relieve, and am, as you have so often called me, ‘a regular born nurse,’ that the profession, if a profession I am capable of acquiring, seems very tempting to me. There is no hurry in the decision, only please think it over, and write me your advice.”

It was not long before an answer came:—