Project Gutenberg's Sunny Boy and His Playmates, by Ramy Allison White This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Sunny Boy and His Playmates Author: Ramy Allison White Illustrator: Howard L. Hastings Release Date: March 2, 2006 [EBook #17902] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SUNNY BOY AND HIS PLAYMATES *** Produced by Al Haines

| CHAPTER | |

| I | LEARNING TO SKATE |

| II | GRANDPA HORTON IS FOUND |

| III | WHO WAS THE BIG BOY? |

| IV | ON COURT HILL |

| V | THE SNOW MAN |

| VI | THE PARKNEY FAMILY |

| VII | THE OTHER GRANDPA |

| VIII | WHEN TOYS GO TO SCHOOL |

| IX | OUT IN THE BLIZZARD |

| X | WHERE THE HORSE LIVED |

| XI | MR. HARRIS BRINGS A LETTER |

| XII | JERRY LOSES HIS TEMPER |

| XIII | BRAVE LITTLE SUNNY BOY |

| XIV | THE EXPLORERS SET OUT |

| XV | ANOTHER RESCUE |

"Santa Claus brought them," said Sunny Boy.

He was lying flat on the floor, trying to reach under the bookcase where his marble had rolled. The marble was a cannon ball and Sunny Boy had been showing Nelson Baker, the boy who lived next door, how to knock over lead soldiers.

Nelson Baker picked up the lead general and examined him carefully.

"They're nicer soldiers than I had last year," he said. "Say, Sunny Boy, I could bring my soldiers over and we could have a real fight."

"I've got it!" shouted Sunny Boy suddenly, pulling his arm out from under the bookcase with the marble in his hand. "I knew it rolled under the bookcase. You can roll it this time, Nelson."

"All right," said Nelson, taking the marble. "And I guess I won't go for my lead soldiers. My mother might say I'd been over here an hour."

Nelson's mother, you see, had told him he might stay an hour at Sunny Boy's house, and something told Nelson he had already played so long with his little friend that if he went home now he would not get back.

"Get down like the Indians," urged Sunny Boy, as Nelson took the marble. "Shut one eye, Nelson."

Nelson put his head down to the floor and closed one eye. He meant to aim straight at the row of beautiful new lead soldiers, but, as he afterward explained, the marble slipped before he was ready. It shot across the floor and went crash into the glass door of the bookcase.

"What was that, Sunny Boy? Did you break anything?" asked Grandpa Horton, coming in from the dining-room, where he had been reading the newspaper. He carried the paper in his hand and his glasses were pushed up on his forehead and he looked worried.

"My marble hit the bookcase door, but I don't believe I broke it," said Nelson. "'Tisn't even cracked, is it, Mr. Horton?"

Grandpa Horton looked carefully at the glass door and said no, the marble had not been able to crack the heavy plate glass.

"But I'd play another game if I were you, boys," he said kindly. "Have you shown Nelson all your Christmas presents yet, Sunny Boy?"

"We got only as far as the lead soldiers," answered Sunny Boy. "Nelson wanted to play with them. But come on up in the playroom, Nelson, and I'll show you my things."

It was only two days after Christmas, and the presents Santa Claus had brought Sunny Boy and the gifts his mother and daddy and grandparents had given him, were all spread out on the window seat in his playroom. The two presents that Sunny Boy liked most were a little pocket searchlight and his ice-skates. The skates were double-runner ones, for Sunny Boy did not yet know how to skate.

"I'm going to learn this winter," he told Nelson. "Grandpa is going to take me to Wilkins Park this afternoon as soon as Daddy and Mother come home from taking a walk."

"I can skate a little," said Nelson. "But my mother won't let me go to the Park alone. Lots of the boys go, but she never lets me. I wish we had a little private pond. Maybe we could make one in the yard, Sunny."

"Maybe," assented Sunny Boy, but he was thinking about going to the Park with Grandpa Horton and trying his new skates, and not about making a "private" skating pond in the back yard. "There! I heard the front door shut. I hope Daddy's come."

Sunny Boy and Nelson ran downstairs to find Daddy and Mother Horton in the hall, taking off their coats.

"Nelson, your mother wants you to come home," said Mr. Horton. "We saw her in the window as we passed your house. She's waiting for you. Your Aunt Caroline has come."

"Take a popcorn ball, Nelson," said Sunny Boy's mother, as Nelson began to put on his coat and hat. "And here is one for Ruth." Ruth was Nelson's little sister.

Nelson said good-bye to Sunny Boy and ran down the steps of the Horton house and up his own. It was never any trouble for Nelson or Sunny Boy to go calling on each other.

"Now we can go skating, can't we, Grandpa?" asked Sunny Boy eagerly. "I thought Nelson stayed ever so long."

"Why, Sunny Boy, how impolite you are!" cried his mother. "That isn't a nice thing to say. Suppose you should go to see Nelson and he should spend the time wishing you would go home—how would you feel?"

Sunny Boy looked uncomfortable.

"Well, he can come back after I go skating," he suggested. "Grandpa promised we could go this afternoon, Mother."

"So I did; and we'll start this minute," declared Grandpa Horton, coming out into the hall and smiling at his small grandson. "Who ever heard of a little boy with a brand-new pair of skates and ice on the pond, not going skating, Olive? Sunny Boy is just as polite as he ever was, Olive, but we have to go skating, whether we have company or not."

"Oh, Father, how you do spoil Sunny Boy!" cried Mrs. Horton, half-laughing. But she kissed them both and waved to them as they went off, the new skates dangling over Sunny Boy's arm and buckled together with a leather strap just as the big boys tie their skates.

"Can you skate, Grandpa?" the little boy asked, as they trudged along, Grandpa's rosy face and white mustache showing above a gray and white muffler and Sunny Boy's pink cheeks and dancing eyes set off by a muffler of scarlet wool. "Will you go skating with me?"

"Why, I haven't been skating for thirty years!" exclaimed Grandpa Horton. "I don't know whether I have forgotten or not, Sunny Boy. But I have no skates, you see, and I shall not get any because I don't expect to go skating often this winter. I'll get you started, and then this winter, when we go home, Grandma and I will be able to think of you having fine times on the ice."

Wilkins Park was several blocks from the Horton's house, but Sunny Boy and his grandfather liked to walk, and though it was a cold day they tucked their hands in their coat pockets and walked fast and were very comfortable. The best skating pond in Centronia—indeed about the only good pond—was in the center of the Park, and long before Sunny Boy and his grandfather came in sight of the Park they saw boys and girls with skates over their arms, hurrying to the pond.

"Hurry, Grandpa!" urged Sunny Boy. "Hurry! Maybe there won't be room for me!"

Grandpa Horton laughed and said he thought there would be room for one small boy on the pond even if half the town did want to go skating that afternoon.

"I suppose it is because there is no school," he said, as they turned in at the Park gates. "I declare, Sunny Boy, if I had thought of it, I don't know that I would have brought you today!"

For the ice-pond—and by this time they were in sight of it—was crowded with skaters. Skating in holiday week was too delightful to be neglected, and it seemed as though all the school children in the city were skating or learning to skate. There were big boys and little boys and tall girls and short girls and good skaters and poor ones. Now and then a long line of skaters, hands joined, swept down the pond, shouting.

Sunny Boy beamed. He was very glad that he had come and he wanted to sit down on the grass and put on his skates at once.

"I think we'll walk around to the other end of the pond, dear," said Grandpa Horton. "There are not so many people there, and I'll be able to walk out on the ice a little way with you till you learn to keep your balance. Don't put on your skates till we get to that white post."

Sunny Boy took his grandfather's hand and they tramped around the pond till they reached a place where there were fewer skaters. A tall policeman was telling a pretty girl that she could not leave her sweater on the bank.

"It wouldn't be there when you got back, Miss," he said. "The only wise thing to do is to carry all extras with you—that is if you want 'em."

The pretty girl skated off, carrying her sweater, and the policeman turned and saw Sunny Boy struggling to put on his skates.

"Well, I guess I know you!" said the policeman, smiling. "You go to Miss May's school, don't you?"

It was the same policeman Sunny Boy had met when all the children at Miss May's school had lost their coats before Thanksgiving (and that was exciting, you may be sure), and they were really very good friends.

"This is my Grandpa Horton," said Sunny Boy. "He and Grandma are visiting us. They came before Christmas."

Grandpa Horton and the policeman shook hands and Grandpa asked him if he thought the ice was safe.

"Oh, it's safe enough, sir," answered the policeman.

"Sunny Boy is so anxious to learn to skate," explained Grandpa Horton, while Sunny Boy stood up, his new skates on his feet by this time, "that I promised him his first lesson today."

"He'll be all right if he stays near the edge and you keep an eye on him," said the policeman. "Sometimes the little fellows get knocked down, if they go out in the center alone. If you tumble, Sunny Boy, don't bump your nose, will you? You might sneeze."

Sunny Boy laughed, and, holding tight to Grandpa Horton's hand, he slowly slid out on the ice.

"I feel—" he gasped, "I feel like a rocking horse!"

And indeed, if you have ever been on double runner skates yourself, you'll remember that you do feel something as a rocking horse must feel.

Grandpa Horton was very patient and he walked slowly and held fast to Sunny Boy so that he would not feel frightened. Boys and girls whizzed by them, laughing and shouting, and Sunny Boy hoped that he would be able to skate like that some day. Presently he let go of his grandfather's hand and tried to skate by himself.

"I can do it, just as nice," he was boasting when one foot went out and the other doubled up and Sunny Boy went down flat!

"Hurt?" asked Grandpa Horton, helping him up. "No one ever learned to skate without a fall or two, Sunny Boy."

"It didn't hurt me," said Sunny Boy bravely. "At least, not very much. But the ice is pretty slippery, isn't it, Grandpa? And it is hard, too."

He took hold of his grandfather's hand again, though, after this tumble, and they were both having a fine time when they heard some one shout.

"Why, it's the policeman!" said Grandpa Horton, in surprise. "I didn't realize how far out we were, Sunny Boy. He's motioning. We must go in. Hurry, laddie!"

The policeman stood on the shore, shouting and waving his arm. As the skaters heard him they began to move toward him, and in a minute there was a pushing, hurrying throng, some skating, some trying to run.

"Everybody ashore!" shouted the policeman. "Everybody off!"

A crowd of skaters rushed for the head of the pond. Sunny Boy felt his hand pulled from Grandpa Horton's and he spun around like a little top. When he stopped spinning he landed on his hands and knees and several boys almost skated into him. Grandpa Horton was nowhere to be seen!

"Look out!" shouted a big boy. "Watch where you're going! Can't you see the little kid?"

"The ice is cracking!" cried another boy. "Look! There's water on the top now. Gee, let me get ashore!"

"Well, go on and get ashore," said the big boy, pulling Sunny Boy to his feet. "Go on ashore! If you're so afraid of drowning you have to walk on a kid of this size, you'd better go ashore."

The other boy had pushed on toward the shore and he did not hear any of this talk. The crowd continued to move by, because all the skaters kept coming. Of course it would have been much wiser if they had gone ashore at different points of the lake instead of crowding together at the end where the ice was already cracking. But, somehow, people do not stop to think when anything happens, and as soon as the boys and girls—and men and women, too—who were skating on the pond saw that something was happening at one end of the pond they skated there as fast as they possibly could.

"You'd get along faster without your skates," said the big boy, "but I won't try to take 'em off for you. We'd both be walked on while I was doing it. Come on, we'll see if these folks are in too big a hurry to let us get ashore with them."

Sunny Boy was not exactly frightened, but he felt rather queer. Grandpa Horton was gone, a strange boy had him by the hand, and many people kept shouting and making a loud noise. And now, instead of clear, smooth ice under his skates, he seemed to be walking through slushy water.

"Don't you get scared," said the big boy kindly. "We wouldn't drown if we went right through the ice. It isn't very deep right here. Look out—here we go!"

Sunny Boy cried out in surprise and a girl ahead of him screamed. The ice seemed to part and let them down gently into the coldest water Sunny Boy had ever felt. He had not known that water could be so cold!

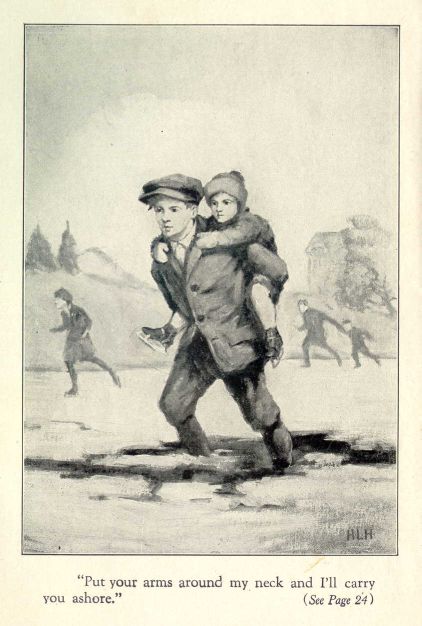

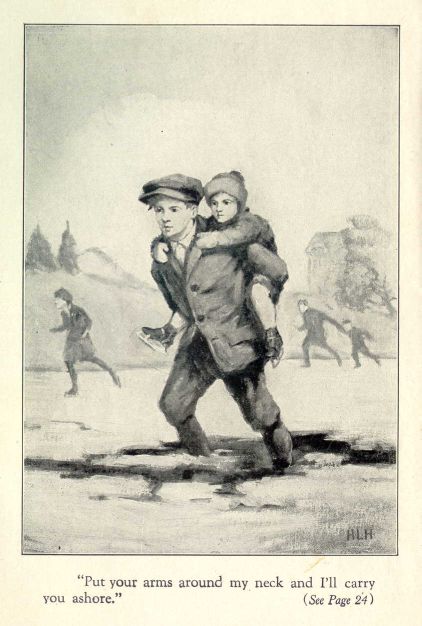

"You're all right," the big boy assured him, "Put your arms around my neck and I'll carry you ashore. The girls make a lot of noise, don't they? Well, in one way it's a good sign—as long as they can scream we know they are not drowned."

The boy had a round, freckled face, and he grinned so cheerfully that Sunny Boy had to smile back. The boy looked blue from the cold and his coat was thin and shabby, if Sunny Boy had only noticed it, but he talked every minute and didn't complain once. He showed Sunny Boy how he wanted him to put his arms, and then he lifted him up and carried him toward the bank.

"Good for you, Bob!" called some one, as the big boy reached the shore.

"There you are," the boy said to Sunny, as he set him carefully down. "Now you take my advice and trot along home and get on dry shoes and stockings. You'll be sneezing your head off to-morrow, if you don't look out."

"But I want my grandpa!" said Sunny Boy, beginning to cry. "I lost my grandpa! Maybe he is all drowned!"

No wonder Sunny Boy cried at this sad thought. He loved his Grandpa Horton very dearly and he was named for him, "Arthur Bradford Horton." To be sure, no one ever called the little lad by that long name, for "Sunny Boy" seemed to suit him so exactly. But, of course, when he grew up and was a farmer or a traffic policeman or the captain of a sailboat—he didn't know yet which he would rather be—he would need his real name. Perhaps you know all about Sunny Boy. If so, we do not have to introduce you. But if you have not read the other books about him you will want to know that he lived with his daddy and his mother and Harriet, who had helped his mother since Sunny Boy was a tiny baby, in the city of Centronia and that Grandpa and Grandma Horton lived on a beautiful farm, "Brookside," where Sunny Boy and his mother had spent a month the summer before. The first Sunny Boy book, called "Sunny Boy in the Country," tells all about this visit and the friends Sunny Boy made there and about the kite he made which got him into trouble. But that ended happily and Sunny Boy was so happy at Brookside that he might have decided to be a farmer if he and his daddy and mother had not gone to the seashore to visit his Aunt Bessie.

"Sunny Boy at the Seashore" tells about the fun a small boy can find in the sand and of Sunny Boy's experiences in sailing boats, and especially about the time he drifted out to sea in a rowboat all by himself. His mother and daddy, in another boat, found him, though, and Sunny Boy thought he would like to be a sea captain like the kind Captain Franklin who ran the motor-boat which caught up with him just as he was beginning to be very much afraid he was lost.

Sunny Boy knew that he could not be a sea captain before he was grown up, and long before that, the very next month, in fact, Daddy and Mother Horton took him to New York City, and, dear me, didn't he find adventures there! He was lost twice and he took his mother shopping and he visited Central Park and the Statue of Liberty and he saw so many things that he kept remembering them long after he was home again. "Sunny Boy in the Big City" is the title of this third book, and the traffic policemen interested him so much that he thought he would put off being a sea captain till he had tried to be a policeman.

In fact the traffic policemen interested Sunny Boy so much that he taught the children on his street to play a game called "City" when he came home from New York, and in this game Sunny Boy was always a policeman. You may have read of how he played "City" in the fourth book about him called "Sunny Boy In School and Out." It was in this book, too, that Sunny Boy made the acquaintance of the big policeman whom he had seen at the skating pond.

Sunny Boy thought of this big policeman as soon as he was safely on shore and as soon as he said perhaps his grandpa was drowned and the big boy had told him no one was drowned—"some of 'em may have been walked on a little, but no one is drowned, I tell you," he said earnestly. Sunny Boy wished he could find this kind man in the blue uniform who might be able to help him find his grandfather.

"Where's the policeman?" he asked, pulling at the big boy's ragged sleeve.

"What you want the police for?" asked the boy, looking at Sunny Boy queerly. "Do you want them to chase you?"

"This policeman won't chase me," said Sunny Boy sturdily. "He is a friend of mine and I like him. Come on and let's hunt for him."

He started to walk higher up the bank and almost fell down.

"Why, I have my skates on!" he cried, in surprise, for he had forgotten them. "I guess I'd better take them off."

He turned to ask the big boy to help him, and he wasn't there! He wasn't anywhere, for Sunny Boy looked all around. The other boy had disappeared as though he had tumbled into the lake, though Sunny Boy was sure he hadn't done that.

"Oh, dear, I wish he had waited," mourned Sunny Boy, sitting down to take off his skates. "I wanted to tell Grandpa about him, and now he's gone."

The skate straps were swollen with water and stiff and cold. Sunny Boy worked at them till his poor little fingers were blue, but he could not unfasten them. So Sunny Boy was ready to cry with cold and disappointment and loneliness when a man spoke to him. It is not strange that a little boy should feel like crying when he has lost his grandpa and his feet are wet and his hands are so cold they ache.

"Are you lost, little boy?" he asked.

He was a short man, and he stared at Sunny Boy so hard through round, black-rimmed Spectacles that the little boy felt rather uncomfortable.

"No, thank you, I'm not lost," he answered politely. "But my grandpa is. I can't find him anywhere."

"Well, well, you don't tell me!" replied the man eagerly. "Why, I heard a grandfather saying back there in the crowd that he was looking for his little grandson. Come along and I'll help you find him."

The short man was very kind, for he knelt down and unbuckled the stubborn skate straps and tied them over Sunny Boy's arm. Then he took his hand and led him back into the crowd up to a worried-looking old gentleman.

"Excuse me, sir, I think I've found your little grandson," he said. "I discovered this little fellow over by the edge of the pond. He is looking for his grandpa."

The worried-looking old gentleman was tall and thin. He had no white mustache and no gray-and-white muffler. He was not Grandpa Horton at all.

"What ails the man!" cried this grandpa, glaring at the short man. "I am looking for my granddaughter and he brings me a lost boy!"

"Oh, my!" murmured the short man, dropping Sunny Boy's hand. "I'm sorry. I'm so absent-minded. I hardly ever get things straight. I thought you said you had lost your grandson. Excuse me," and he turned and stepped back into the crowd, leaving Sunny Boy alone again.

This other grandpa stared at Sunny Boy silently for a few minutes and Sunny Boy stared back. Then the old gentleman threw back his head and laughed and laughed. He laughed so heartily that Sunny Boy had to laugh, too, though he could not see that there was anything funny to laugh at.

"Well, poor James Ridley has made a mess of it as usual," said the old gentleman, when he could stop laughing. "I suppose, because I called Adele my little girl, he went about looking for a child. She is seventeen and able to take care of herself almost anywhere. Well, child, if I were your grandfather I'd want some one to look after you, so suppose you stay with me till we see if your grandpa is here. He wouldn't go home without you, that much I know."

Sunny Boy felt better, with a tall, kindly old gentleman to walk about with him, but he wished that they could find Grandpa Horton before his feet were too cold to walk on. And then, just as he was sure his shoes were frozen fast to his toes, he saw dear Grandpa Horton!

"Grandpa!" he shouted. "Here I am, Grandpa! We've been looking all over for you."

"And I've been about crazy, looking for you," said Grandpa Horton, hurrying up to them. "Are you all right, Sunny Boy? Are you cold? Are you wet? How did you get ashore?"

The other grandfather laughed again as he shook hands with Grandpa Horton.

"He's all right, though I suspect his feet are pretty wet," he said. "I would have bundled him off home, but I knew you would be terribly anxious and I couldn't pick you out of the crowd without his help. You'd better hurry, now. I'm going to get out of this crowd as soon as I find my granddaughter."

Grandpa Horton thanked the old gentleman for taking care of Sunny Boy and then they shook hands again and Sunny Boy and his grandpa hurried toward the Park gates.

They walked as fast as they could all the way home, and sometimes they ran a little. Grandma Horton, who had been taking a nap when they left for the Park, was downstairs in the living-room with Mrs. Horton, knitting, when she happened to look out of the window and see Grandpa and Sunny Boy coming.

"Has anything happened to you?" she cried, opening the door as they dashed up the steps. "Are either of you hurt?"

Dear, dear, there was a great deal of excitement, you may be sure, when Sunny Boy and Grandpa told what had happened at the pond. Harriet brought hot water bottles and dry shoes and stockings and hot lemonade and her best box of peppermint drops. Grandma Horton insisted on wrapping Sunny Boy from chin to feet in a hot blanket and she made Grandpa take little white pills. Mother Horton rubbed their hands and lighted the electric heater, although the room was very warm and comfortable, and put on all the wood in the fire-basket till the fireplace was ablaze with flames.

And all this loving care and attention agreed with both Sunny Boy and Grandpa Horton, for neither one of them took the tiniest bit of cold and they were all right again the next day. Sunny Boy said he knew it was the peppermint drops, and Harriet thought so, too.

Although Sunny Boy and Grandpa were quite well the next morning, Daddy Horton said he thought they had better stay in the house till after lunch.

"It is much colder to-day. The thermometer dropped several degrees last night," Daddy explained. "I think if you wait a few hours you'll find it pleasanter out."

So Sunny Boy and Grandpa took this good advice and stayed in by the living-room fire. They again told Grandma and Mother Horton about the ice cracking, and Harriet, who was cleaning the dining-room, could not get along very fast with her dusting because she was always coming to the door to listen.

"That must have been Judge Layton, Father," said Mrs. Horton, when Grandpa described the old gentleman whom Sunny Boy insisted on calling "the other grandpa."

"I believe I did hear some one in the crowd call him 'judge,'" answered Grandpa Horton.

"He has a granddaughter, Adele, I know," said Mrs. Horton. "And he is so proud of her he goes everywhere with her. I hope he found her and that she was not hurt."

"Oh, no one was hurt," replied Grandpa Horton. "There was a great deal of shouting and screaming, but a pair of wet feet was the most any one suffered, I feel sure. What is it, laddie?"

Sunny Boy had been standing quietly beside his grandfather's chair, waiting for a chance to say something very important.

"I wish, Grandpa—" he began excitedly, "I wish the big boy who pulled me off the ice had waited to see you. He was afraid of the policeman, or maybe he might have stayed."

"I wish I had seen him," said Grandpa Horton seriously. "He must have had his wits about him to get you out of that crowd so easily. That was what was worrying me all the time—I was afraid that a little chap like you would be knocked down by that struggling crowd."

"I wish I could see the boy," said Mrs. Horton wistfully. "I would like so much to thank him, and Daddy would, too. Don't you even know his name, Sunny?"

Sunny Boy shook his head.

"I forgot to ask him," he admitted.

"Well, never mind," said Grandpa cheerily. He did not believe, he often said, in feeling sad over things you could not help. "Perhaps we will see him again. You would know him, wouldn't you, Sunny Boy, if you should see him on the street?"

"Ye-s, I guess I would," answered Sunny Boy. "His coat was ripped in the back and where it didn't button, and he wore a blue sweater with green buttons. I would know the green buttons, Grandpa."

Grandpa Horton laughed, but Mrs. Horton and Grandma looked grave.

"I'd like to knit him a good sweater," said Grandma. "Like as not the child needs warm things to wear."

"Boys wear old clothes to skate in, of course," Mrs. Horton said. "But last night when Sunny Boy told me how rough and red his hands were and that his skate straps were tied with string, I wondered if he wasn't a boy from the River Section. He may need more than our thanks for taking care of Sunny Boy."

"We'll go out and try to find him after lunch," promised Grandpa. "Shall we, Sunny Boy?"

"Oh, yes, let's!" cried Sunny Boy joyfully. "Let's go skating again, Grandpa."

And after lunch they put on their mufflers and overcoats and caps and Sunny Boy hung his skates on his arm and they set out for Wilkins Park and the skating pond.

But first Mother had to kiss Sunny Boy and Harriet had to kiss him and they all waved their hands to him till he and Grandpa turned the corner and could not be seen from the house any more.

"We have to find the big boy, don't we?" said Sunny Boy, trying not to gasp as the wind blew down the avenue and almost took his breath away.

"Yes, we must be on the look-out for him," Grandpa Horton replied. "I have an idea he may be at the pond."

But, though they looked carefully when they came to the skating pond, they could not find a boy who looked like the one Sunny remembered. The pond was crowded again with skaters and they were laughing and singing as though they had never heard of the ice cracking.

Sunny Boy put on his skates, and this time he had better luck with his lesson. Grandpa said he was doing finely. And, indeed, he did not fall down more than twice, and one of those times, as he explained, was a mistake. Another boy skated into him and "tipped him over," Sunny Boy said. Just as Grandpa said it was time to stop, Sunny Boy looked up and saw his friend, the tall policeman, standing on the shore.

"Hello!" called the policeman, as Sunny Boy and Grandpa Horton came close to the shore. "Thought you'd try it again, did you? Where were you yesterday during the big excitement?"

Sunny Boy sat down on the bank to take off his skates and Grandpa Horton told the policeman what had happened to them.

"Do you know, I thought about the little chap," said the policeman kindly. "I knew you were with him; but I said, suppose the crowd tears 'em apart from each other? I know what a crowd can do when it loses its head, you see. All the time I was telling girls they were not drowned, I kept one eye open for the little boy, but I didn't catch a glimpse of him. You say an older lad pulled him ashore?"

"Yes, and he ran away when I said I was going to try to find you," said Sunny Boy, standing up, now that the skates were off. "He was just as nice, but he is afraid of policemen."

"Then he is a silly boy, and you tell him I said so," answered the tall policeman promptly. "Of course a bad boy might not want to see me; but this was a mighty good lad, to my way of thinking. He has an old head on young shoulders, to get you out of such a mix-up without a scratch."

But the policeman could not tell them who the big boy was, of course; and after they went home, and found that Mother and Grandma had a bowl of good, hot, buttered popcorn for them, Sunny Boy and Grandpa continued to talk about the lad in the poor, torn coat and to wish they could find him. Daddy Horton, too, at dinner that night said he would rather find the boy than a ten dollar goldpiece.

"I'm afraid he is a lad who needs some help," he said anxiously; "and we would be so glad to do anything for him. I must see some of the men who work over in the River Section and try to get them to hunt him up."

And Mr. Horton did interest several people in his search for the big boy, but when they reported, one by one, that they could find no boy who had carried a little boy ashore at the skating pond, he began to think that perhaps the boy did not live in the River Section, after all, but in some other part of the city.

While Mr. Horton was trying to find the boy who had been so good to his little son, Sunny Boy was having great fun. There was no school, of course, during the holidays, and, after two days of skating, there came a heavy fall of snow. When Sunny Boy woke up and saw the roofs all white, his shout wakened Daddy and Mother.

"It snowed!" shouted Sunny Boy, dancing up and down in his white flannel sleeping suit. "Oh, Mother, it snowed! I can use my new sled, Mother!"

"Well, for pity's sake!" cried Daddy Horton, pretending to be very cross. "What is all this fuss about? All over a little snow? Why, I don't think snow is half so nice as rain!"

"Oh, Daddy!" Sunny Boy climbed into bed with his father and put his arms around his neck. "Daddy, boys with new sleds like it to snow. I'm going coasting right after breakfast."

"Oh, you are, are you?" said Daddy, beginning to tickle Sunny Boy. "Maybe you'll have to study spelling or something like that, instead." And then Sunny Boy began to tickle his father and they rolled and tussled and threw pillows at each other till Mrs. Horton, who was brushing her hair, declared she had never seen such a looking bed!

"No one can go coasting," she said firmly, "who doesn't get up this minute and start to get dressed!"

And then Daddy Horton jumped out of bed on one side and Sunny Boy fell out on the other and Daddy chased him into his room and they had another pillow fight in there. Sunny Boy laughed and squealed so much that Grandpa Horton came and tapped on his door and asked him what all the fun was about.

Dear, dear, Sunny Boy was so excited that he could hardly get dressed and he was going downstairs without having brushed his hair. But Mother called him back and brushed it neatly for him. Before Sunny Boy could eat his oatmeal he had to go down into the laundry where his new sled was and bring it upstairs and put it in the front hall. Santa Claus had brought him the sled for Christmas as well as the skates.

"Do you want to go coasting, Grandpa?" asked Sunny Boy eagerly.

"Well, no, I don't believe I do," Grandpa Horton replied. "You see, your daddy asked me to go down to the office with him this morning, and I think I will. Perhaps I'll come around and see you coast down once or twice, if not to-day, to-morrow. Is there a good hill for coasting in this neighborhood?"

"There is only one hill in the whole city," Mrs. Horton explained. "I suppose all the children in Centronia will be there this morning. Don't you think Sunny Boy is too little to go alone, Daddy?"

"Oliver Dunlap and Nelson Baker will go, Mother," said Sunny Boy anxiously. "All the fellows are going, Daddy."

Mr. Horton laughed and gave Harriet his cup for more coffee.

"I think Sunny Boy will be all right," he said. "I know that new sled will rust its runners if it isn't used pretty soon. Sunny must not stay a minute later than you wish him to, and if the hill is too crowded, let him come home. You can have fun with your sled in more ways than just using it for coasting, you know, Son."

"Your grandmother and I are going over to Aunt Bessie's for lunch, dear," Mrs. Horton said to Sunny Boy, who had already finished his breakfast. "Harriet will give you yours. Don't stay out on the hill longer than half-past eleven. Have you your sweater on, precious?"

"Yes'm," nodded Sunny Boy. "May I be excused, Mother? That's Nelson whistling for me. I won't forget. Good-bye. I have to hurry." And he kissed his family in great haste and ran out into the hall for his overcoat and mittens and sled.

"Hello!" called Nelson Baker, as Sunny Boy came out on his front steps, dragging his new sled with him. "Did you know it snowed in the night? Can you go coasting?"

"Yes. And let's stop for Oliver," suggested Sunny Boy. "Oh, Nelson, your mother is rapping on the window for you."

"Gee, I bet Ruth wants to go coasting," said Nelson crossly. "I never wanted to do anything in my life, Ruth didn't want to, too. I think girls are just horrid!"

"Nelson!" called Mrs. Baker, raising the window, "wait just a minute, dear; Ruth wants to go coasting, too. She will be right out."

"I told you so!" groaned Nelson. "Now I can't have a hit of fun. Ruth will cry because the sled goes too fast and she'll cry because her feet are cold and she'll cry because she gets tired walking up the hill. And then she will want to come home just when I am having a good time and I'll have to bring her. I wish Mother would make her stay in the house."

Before Sunny Boy could answer him, Ruth came out. She was a pretty little girl, about four years old, and she wore a fur hat and a dark red coat with a fur collar. Her muff was tied to a string which went around her neck. She had her own sled, a little one.

"Hello, Sunny Boy," she said, smiling. "Santa Claus brought me a sled, too."

"What do you want to go coasting for?" asked Nelson, not waiting for Sunny Boy to answer. "Your feet will get cold."

"They won't, either!" cried Ruth. "Anyway, I'm going with you—Mother said I could. So there!" and she stamped her foot in its shiny new rubber.

"All right, come on then," said Nelson crossly. "What are you waiting so long for? Sunny Boy and I could have a lot more fun if you stayed at home."

Sunny Boy was so afraid Ruth was going to cry at this unkind speech that he tried to think of something to say that would make her forget it.

"You sit on your sled and Nelson and I will pull you," he told Ruth. "You can hold my sled for me."

This pleased Ruth very much, and she sat down on her sled and tucked her coat around her and stuck her fat, short little legs, in their gray leggings, straight out in front of her.

"Take my sled, too," said Nelson, forgetting to be cross. "Don't fall off, because we are going to go fast."

"Let's play we are fire horses, going to a fire," suggested gunny Boy. They had some automobile fire apparatus in Centronia, but the engines were still pulled by horses. "Can you pull two sleds, Ruth?"

"Oh, my, yes," replied dear little Ruth.

If the boys had asked her to pull six sleds she would have tried her best to do it. It did seem too bad that when she wanted to go with them and tried so hard to please them, that they so often wished her to stay in the house and play by herself. That is, Nelson did.

"Hang on," said Nelson now, and away went the two fire horses, pulling the fire engine.

Ruth nearly fell off when they started, for they jerked the sled, but she managed to hold on. The two sleds bumped wildly behind her, but she held the ropes tightly and never cried out even when the boys pulled her over a curb-stone and her sled tipped far to one side.

"Toot! Toot!" cried Sunny Boy, trying to whistle, and not doing it very well because it is difficult to run and pull a sled and whistle, all at the same time.

"Nelson!" called Ruth, as they bumped her down another curbstone. "Oh, Nelson! Say, Sunny Boy, wait a minute!"

"We can't stop! We have to get to the fire!" cried Nelson, panting. "When we get to the fire we'll stop."

"But wait a minute!" begged Ruth, "I want to tell you something."

The two little boys pretended to kick up their heels and snort as they had seen the fire horses do, and they would not stop. They galloped and pranced and tried to run faster. At last they had to stop to get their breath. Their cheeks were red and they were as warm as toast.

"Why—why—" stammered Sunny Boy, looking back at Ruth who sat on her sled with her hands in her little fur muff. "Why, where are our sleds?"

"I dropped the ropes 'way back on Greene Street," replied Ruth calmly. "I asked you to stop and you wouldn't."

"Well, you might have said you lost the sleds," said Nelson. "Then we would have stopped. Gee, I hope nobody took 'em! We'll have to go back."

Ruth got off her sled and walked back with the two boys. They found the sleds on the sidewalk, exactly where a sudden jerk of the sled she was on had made Ruth drop the ropes. Even Nelson could not scold his sister when the sleds were so easily found, and as they went back toward the hill he and Ruth and Sunny Boy took turns riding.

As Mrs. Horton had said, every boy and girl in Centronia was at Court Hill, the one good spot for coasting in the city. At least it seemed that every boy and girl had had a sled for a Christmas gift, or had one left from the year before, or had borrowed one from some one who had two, and all had trotted through the snow to enjoy the fun. Since there was no school, there were high school and grammar and primary grade children, as well as the little folks who went to kindergarten or to Miss May's school, the small, private school where Sunny Boy went. Nelson Baker went to public school where Sunny would go when he was a little older, Daddy Horton said.

"There's Perry Phelps and Jimmie Butterworth," cried Sunny Boy, as he caught sight of two of his schoolmates. "Look at the crowd! Oh, Nelson, see this sled coming down!"

A large sled shot by the children, filled with a crowd of high school boys and girls.

"I don't believe I want to coast," said Ruth. "I'm not exactly afraid, but I don't like it. Let's stay down here and watch them, Nelson."

"You can stay," Nelson answered. "But I want to coast. Sit down on your sled by this stone and you can watch me coast."

But this didn't please Ruth. She didn't want to be left alone with only her sled for company. She wanted the boys to stay with her.

"You'll like it when you are used to it," urged Sunny Boy. "Come on, Ruth, there are ever so many girls coasting. You can steer as well as that girl in the green coat."

He pointed to a little freckle-faced girl who came down the hill on a shabby old sled and steered it neatly out of the way of every sled she met.

"No, I couldn't do that," said Ruth. "But I'll coast with you, Sunny. I can hang on to you."

Sunny Boy had meant to coast down the hill a few times by himself, for he had not had a sled last year and he was not sure he knew how to steer. But, of course, if Ruth had made up her mind to coast with him on his sled, Sunny Boy felt that there was nothing to do but take her.

"I'll go first! Watch me!" cried Nelson, scrambling up the hill ahead of them. He plumped himself on his sled, pushed with one foot, and away he flew down the hill.

"That looks just as easy," said Sunny Boy to himself.

He had to wait a minute to find a place for his sled in the row of coasters lined up at the top of the hill. Then he sat down and took the rope and Ruth sat down behind him and grasped the belt of his coat.

"Here, I'll start you," offered a boy, who came up behind them.

"Wait a—" began Sunny Boy. He meant to say, "Wait a minute," but the boy gave him a tremendous push and the sled slid over the hill and began to go down.

"Ow!" shrieked Ruth, closing her eyes and opening her mouth very wide. "Ow! Stop Sunny Boy! Ow! Ow!"

Sunny Boy couldn't stop. But he was steering nicely and they would probably have had a fine coast if Ruth had not grown more frightened and thrown her arms around his neck. Her elbow knocked Sunny Boy's cap over his eye and he felt himself being pulled over backward. The sled went zigzagging down the hill for a moment, then a big sled tore past it and knocked it to one side. Ruth fell off and dragged Sunny Boy with her and the sled went on down the hill alone.

Nelson had seen the spill at the bottom of the hill and he came running up to them.

"Are you hurt, Ruth?" he asked his sister. "Did another sled hit you? There's Jimmie Butterworth with your sled, Sunny Boy."

Ruth was not hurt, and neither was Sunny Boy. And tumbling off a sled when you are coasting is rather fun if you do not get frightened. Unfortunately, Ruth was frightened and she began to cry and say she wanted to go home.

"I knew you'd want to go home," scolded Nelson. "You can't go. I haven't had but one coast. Come on, and ride down on my sled."

"I don't want to ride on your sled," sobbed Ruth. "I want to go home; my feet are cold."

"Well, you'll have to wait till I have some fun," said Nelson. "What did you do with your sled?"

"I don't know," wailed Ruth. "My feet are cold."

"Step on them and they won't be," said Sunny Boy kindly. He meant that Ruth should walk or run a little and then her feet would be warmer.

"I don't want to step on them!" Ruth cried. She was very unhappy indeed. "I want my sled. I want to go home. My feet are cold."

"I'll find your sled," Sunny Boy promised, and he went up to the top of the hill. After a little tramping around in the snow he found Ruth's sled where she had left it. No one had touched it.

Sunny Boy came running back to Nelson and Ruth, dragging the sled, and just as he came up to them he heard Ruth say: "I'll go home by myself, then."

"You can't!" scolded Nelson. "Mother said you musn't cross streets without me. And I'm not going home as soon as I get here. I want to coast. You'll have to wait till I've had some fun."

Ruth was crying now and her little nose was red from the cold. She looked so forlorn and uncomfortable that Sunny Boy's kind heart felt sorry for her. He was anxious to coast and he hated to go home before he had had any good times with his new sled, but he did not want Ruth to cry.

"I'll go home with you," he said. "You sit on the sled and I'll pull you."'

"Gee, will you take her home?" asked Nelson, in surprise. "That's great! And then you can come back and we'll have packs of fun."

"All right," said Sunny Boy, though he was quite sure he couldn't come back. It would be half-past eleven, he knew, before he could get home and leave Ruth and come back to Court Hill; and Mother had said he must stop coasting at half-past eleven. So, you see, he was really very kind and good to take Ruth home and give up his own coasting fun to make her happier.

Ruth sat down on her sled and held fast to Sunny Boy's sled, and he pulled her all the way home, though she was a fat little girl and pretty heavy for one boy to pull. And as soon as they were home again and Ruth and her sled had gone into her house, Sunny Boy trotted around to the kitchen door of his house to ask Harriet what time it was.

"Half-past eleven, just," answered Harriet. "Did you have a good time?"

Poor Sunny Boy! When Harriet said it was half-past eleven he felt like crying himself, though of course a boy six years old doesn't cry about anything if he can help it.

"Did you have a good time coasting?" asked Harriet again. She was getting lunch ready and Sunny Boy was sure he smelled chicken soup.

"I didn't have any time," he explained sadly. "I tipped Ruth off the sled and then she wanted to come home and I had to come with her, 'cause her mother won't let her cross streets all alone."

"And I suppose Nelson wanted to stay and enjoy himself," said Harriet. "Well, never mind, Sunny Boy, next time you shall coast all morning, if I have to go along to see that no one bothers you."

"Could I go this afternoon, Harriet?" asked Sunny Boy. "Mother didn't say not to; she just said to come home at half-past eleven."

"Yes, I know she did," answered Harriet, putting salt in her soup and then tasting it to be sure it was right. "But I don't think she wants you to play on Court Hill in the afternoon when there will be a larger crowd. I tell you what you do this afternoon, Sunny Boy: Build the biggest snow man you can in the yard and then you'll surprise your mother and grandmother when they come home from your Aunt Bessie's."

"I could s'prise 'em, couldn't I?" replied Sunny Boy, chuckling in delight. "And Daddy and Grandpa, too! Do you think I could make a very big snow man, Harriet?"

"I don't see why not," said Harriet. "You have a yard full of snow to make him out of."

Sunny Boy was hungry, but he was so eager to begin to build his snow man that he would have hurried through his lunch and skipped the bread and butter entirely if Harriet had not said that he could not go out to play at all unless he ate the things she gave him.

"Now I'm through," he declared when he had eaten even the crusts and his glass of milk was quite empty. "Now may I build the snow man, Harriet?"

"Yes indeed you may," said Harriet. "And here is the old broom I promised you, and the felt hat. Do you know how to build a snow man, Sunny Boy?"

Sunny Boy was sure he did, and he went out into the yard, where the snow was piled white and smooth and not even a path had been shoveled, and began to roll a snowball to make the snow man.

"Hello, Sunny Boy, coming coasting?" called Oliver Dunlap.

He had rung the bell and Harriet had told him Sunny Boy was in the back yard. So Oliver had walked through the house, scattering snow at every step, and out through the kitchen to the back porch where he found Sunny Boy beginning his snow man.

"Aren't you going coasting?" called Oliver again. "Come on, Sunny Boy. Nelson and Ruth have gone to dancing school and we can have heaps of fun."

"I have to build a snow man," replied Sunny Boy. "I want to surprise my grandpa. Do you want to help build him, Oliver?"

"Why, I don't mind," said Oliver. "Wait till I bring my sled in. I left it out on your front steps."

He ran through the house, and when he came back in a few moments there were four other boys with him. They brought in a good deal of snow, but Harriet did not mind; she said she would rather sweep up snow than mud, any time.

"Here's Jimmie Butterworth, Sunny Boy," cried Oliver, as the five lads tumbled down the steps, "and Perry and Leslie and Harry. We'll all help you build a snow man."

Sunny Boy was glad to see his friends, and the snow man grew very fast with six boys to work on him. First they rolled the biggest snowball you ever saw. It took pretty nearly all the snow in Sunny Boy's yard, and he and the other boys had to go into Nelson Baker's yard and get more snow to make a head for the snow man.

The great big snowball made the body of the snow man and a smaller ball was his head. They made him arms, too, and stuck a broomstick through one so that he looked, a little way off, as though he were carrying a gun.

"He ought to have some face," said Sunny Boy, when they had this much done.

"Get some coal," suggested Oliver. "You can make eyes and a nose and a mouth with pieces of coal."

Sunny Boy went into the house and asked Harriet if he could, have some coal to make a face for his snow man.

"Take some coal for his eyes," said Harriet. "And here is a strip of apple skin which will make him a handsome mouth. And perhaps the boys would like an apple to eat. I'll put half a dozen in a basket for you."

Sunny Boy took several pieces of coal from the scuttle standing near the kitchen range and a piece of apple skin Harriet gave him and the basket of apples. The boys ate the apples right away and let the snow man wait for his eyes and mouth.

"You put in his eyes, Sunny Boy," said Oliver, when his apple was eaten and even the core had disappeared. "You put in his eyes and I'll fix his mouth."

"Let me put on his hat," begged Harry Winn, when eyes and mouth were in place. "Get out the way, fellows, and let me put on his hat."

They all wanted to put the snow man's hat on for him, all except Sunny Boy. He had several broken bits of coal left over and he wanted to put those down the front of the snow man so that they would look like buttons on his coat.

"I'm going to put the hat on," said Harry.

"I'll fix the buttons now," Sunny Boy said happily.

Harry snatched the old felt hat Harriet had given to the snow man from Oliver, who held it. Oliver made a dash for Harry and the other boys tried to trip him. Around and around the yard they went, laughing and shouting, while Sunny Boy calmly stuck pieces of coal down the white front of the snow man and pretended they were buttons on his coat.

"I said I'd do it!" shouted Harry, jumping for the snow man and landing half way up his back.

He meant to clap the hat on the snow man's head and jump back. But, before he could do this, the other four boys tumbled on top of him and the snow man. Over went the whole statue, and the two huge balls of snow fell squarely on Sunny Boy, just as Daddy and Grandpa Horton, who had come home from the office early, stepped out on the back porch.

Sunny Boy was too surprised to be frightened, and before he had time to wonder what had struck him, Daddy had him out and was brushing the snow out of his ears and eyes.

"Are you hurt, Sunny Boy?" asked Harry. "I didn't mean to knock the snow man over, honestly I didn't."

"There's snow down my neck," said Sunny Boy, wriggling. "But nothing hurt me. Only the snow man is all gone."

There he lay, that beautiful snow man, in two pieces, several pieces in fact, for the balls had broken apart when they fell.

"Never mind," said Daddy Horton cheerfully. "You can easily build another snow man. And the boys will help you, perhaps tomorrow."

"To-morrow is New Year's," announced Oliver Dunlap. "I have to go to see my grandma. But I can help build a snow man the day after that."

The other boys promised to help build another snow man whenever Sunny Boy asked them to, and then, as they were going into the house, Mrs. Baker called to Daddy Horton.

"Wait a minute, Mr. Horton," she said, hurrying out with a scarf tied over her pretty hair. "My nephew just telephoned to know if he could take Nelson and Ruth bobsledding on the hill before dinner. They are at dancing school this afternoon; but I wonder if you wouldn't let Sunny Boy go. He hasn't had any fun at all to-day. This morning he came home with Ruth because she was cold and cried, and then this afternoon the snow man fell on him. My nephew is very careful, and he would be glad to take all these boys. May I tell him they will meet him at the Hill? He is on the 'phone now."

"Oh, Daddy, let me go!" cried Sunny Boy. "I never went on a bobsled. Please, Daddy."

Mr. Horton knew Blake Garrison, Mrs. Baker's nephew, and he knew he was careful and very fond of younger children. Blake was a senior in high school and had a splendid sled. It was just like him to think of his little cousins and to want to give them pleasure. So Sunny Boy was allowed to go, and the other boys went with him. They had all started to go coasting anyway, they explained to Mr. Horton, when they passed Sunny Boy's house and Oliver told them about the snow man. Their mothers would not worry, they said, if they came home by five o'clock.

"Hello, everybody!" said Blake Garrison, when the six small boys found him at the top of Court Hill. Most of them knew him by sight and he, it seemed, knew all their names. "I'm glad you didn't all go to dancing school. Do you feel like a little coast?"

"Let me steer, Blake?" asked Harry Winn.

Blake and another boy, Fred Carr, who was with him, laughed.

"I'll do the steering, Harry," said Blake firmly. "You other youngsters pile on where you please, but I'll keep Sunny Boy near me. If he fell off we might lose him entirely, he's so little."

Sunny Boy smiled, but he did not say anything. He was having a beautiful time. The six small boys got on the sled, and Blake and three other high school friends of his got on, too. The big bob started. Sunny Boy closed his eyes. My, how the wind whistled! How the snow flew up and stung their faces! And how soon they came to the bottom of the hill and shot across the little bridge that was at the foot.

"Do it again," said Sunny Boy to Blake.

They did it again, half a dozen times in fact, before Blake and Fred said that it was quarter to five and time to stop. Then they put the small boys on the sled and gave them a ride home. Blake said no one need say "thank you" to him, because he had had more fun than anybody!

That evening, as Sunny Boy sat in Grandma Horton's lap after dinner and watched the fire burn merrily in the grate, he remembered that Oliver had said the next day would be New Year's Day.

"What do we do on New Year, Grandma?" Sunny Boy asked curiously.

"Oh, people come to see us," replied Grandma Horton, giving him a kiss. "And you may pass them the New Year's cakes that Harriet has baked for us. You will like that, won't you?"

"Happy new year, precious!" said Mother, coming into Sunny Boy's room to put down his window the next morning.

"Happy New Year, Sunny Boy!" cried Grandpa and Grandma Horton, when they met him in the hall on the way to breakfast.

"Happy New Year, Son!" said Daddy Horton, catching him in his arms and lifting him as high as the Christmas tree which still stood in one corner of the parlor.

"Happy New Year, Sunny Boy!" cried Harriet, waving a dish towel at him when he peeped into her kitchen.

"I think New Year is nice," said Sunny Boy, when Mother said he might have two waffles for his breakfast because of the holiday. Usually Mother said that hot cakes were not good for little boys.

After breakfast Sunny Boy brought down his lead soldiers from the playroom and played with them on the rug before the fire place. This was the last day the Christmas tree would be left standing, Mother Horton said, so he liked to stay near it.

"When will it be time to pass the New Year cakes?" he asked Harriet, when she came in to bring more wood for the fire.

"This afternoon," she answered. "When the callers come."

Sunny Boy's Aunt Bessie came to dinner, which was at one o'clock as on Sunday, and Sunny Boy was very glad to see her. She brought him a little set of bells and showed him how he could play a tune on them by striking them with a wooden mallet. Sunny Boy could play "Annie Laurie" before the afternoon was over.

After dinner came visitors. They were all grown up people, and Mrs. Horton and Aunt Bessie gave them tea to drink and sandwiches from the tea wagon and Sunny Boy, in his best white flannel sailor suit, passed them the plates of New Year cakes which Harriet had baked. They were delicious little cakes with caraway seeds and pink sugar on them, and Sunny Boy had three for himself.

It was nearly six o'clock before the "company" as Sunny Boy called them, had gone. Then, to his surprise, his daddy came into the parlor with his overcoat on and his hat in his hand.

"Olive," he said to Sunny Boy's mother, "I'm going over to Dover street in the River Section for a short call. Father is going with me. We heard this afternoon of a family who are pretty hard up."

"Is there anything I can send them?" asked Mrs. Horton. "Harriet will heat up some soup and you can carry it in the vacuum bottle."

"Let me go with you, Daddy?" begged Sunny Boy. "I can carry some New Year cakes."

"We are not going to take anything till we find out what is needed," answered Mr. Horton. "From what I've heard, I'm afraid that this family was overlooked at Christmas. The husband is out work and there are several children."

"Who are the children?" asked Sunny Boy, when his daddy and grandfather had gone. "What are their names, Mother? Are there any little boys?"

"I don't know, precious," replied Mrs. Horton, "but I think likely. Suppose you and I and Grandma go upstairs and look through the Square Box and see if we have some clothes to send them. I am pretty sure Daddy will come back and tell us that they need warm clothes."

Sunny Boy knew all about the Square Box. It stood in the hall closet next to the bathroom, and in it Mrs. Horton put all his clothes that were too small for him to wear and all the clothes her friends gave her, and her own clothes and those of Mr. Horton's that they could no longer wear. Everything was cleaned and mended before it was put in the box, and then, when she heard of some family who did not have enough clothes to wear in winter, or who needed something clean and cool in summer, Mrs. Horton could go to the Square Box and find just what was wanted.

"I hope you didn't give away everything for Christmas," said Grandma Horton anxiously.

Sunny Boy hoped so, too. He knew that his mother had sent several bundles of clothes away at Christmas time and the minister had telephoned her twice for clothes for his poor people. But Mother Horton said there were still some clothes left in the Square Box.

"Here is a good coat for a little girl and three sets of underwear for a man," she said, when they had opened the box. "And this is a warm dress for the mother, if she needs one. And if Daddy comes home and tells us he needs other things for the family, we'll get them for him."

"Are there any little boys?" shouted Sunny Boy, as soon as his daddy opened the front door.

Daddy and Grandpa Horton were covered with snow, for it had begun to snow again. They were cold and hungry, too, and Mrs. Horton said that Harriet should put the hot supper on the table and they could talk while they ate.

"I'd like to have that family up at Brookside just a month," declared Grandpa Horton, stirring his tea. "I tell you, Olive, we don't have such cases in the country. There's a man and wife and seven children, living in two rooms."

"Did they have any Christmas?" asked Grandma Horton.

"Not a sign," said Grandpa Horton. "The man has been out of work for two months and he won't go near the charity bureau. He has an injured arm and he ought to be under a doctor's treatment. There's a boy sick in bed, too, with a heavy cold, and the mother is about ready to give up. But they won't take charity—say they'll starve first."

"We built them a fire," Mr. Horton explained. "And I went out and bought them food for a good supper—told the man he could pay me when he got work. I think I can make him see a doctor to-morrow. And I must find a job for him."

"I have some clothes in the Square Box," said Mrs. Horton. "I can get more, if you will persuade them to accept such things. I don't think they ought to refuse because of the children. If Sunny Boy had no warm coat to wear I think I'd take one from any one who would give it to me."

"I could take the sick boy a New Year cake," declared Sunny Boy, who had been listening. "Is he as big as I am, Daddy?"

"I should say he was about fourteen years old," replied Mr. Horton. "I don't know but I will take you to-morrow morning, Sunny. You'll see some children who didn't get even a candy cane from Santa Claus."

Sunny Boy glanced across the hall. From where he sat at the table he could see his Christmas tree.

"I'll take them my candy canes," he said. "Mother is going to take the tree down tomorrow. I ate only two canes, Daddy, so there are enough left."

"All right," answered his daddy. "You may take the children anything you wish. That family can use anything, and we won't let them refuse our help. They'll be on their feet again the faster if they accept aid before they are all discouraged."

The next morning Sunny Boy and his grandpa had to go alone to see the poor family. From Daddy Horton's office came a telephone message that he must come and see a man on very important business before nine o'clock, and he had only time to eat his breakfast and run for a car. But Grandpa Horton promised him that he would see to the Parkneys. That was their name—Mr. and Mrs. Parkney and Bob, Joe, Elsie, Alice, Kitty, Ned, and Charlie Parkney. Grandpa Horton had the names written down on a slip of paper.

"Are you sure the sick boy hasn't anything he can pass on to Sunny Boy?" asked Mrs. Horton, a little bit worried as she tied up a bundle for them to carry. "You are sure it is only a cold?"

"Sure," said Grandpa Horton. "Positive. The poor lad is as hoarse as a crow. Got the New Year cakes and the candy canes, Sunny Boy? Then I think we are ready to start."

Sunny Boy had found seven candy canes on his Christmas tree and he had wrapped each one separately. There would be a cane for each Parkney child. Harriet had helped him make seven little packages of cakes. And, with Daddy's help, the night before he had picked out a toy for each child. He could not go to sleep until he had chosen the toys. Though, of course, he did not have anything especially for girls, he thought they would like the games and the jack-in-the box, and Mother Horton said she knew they would.

It was lucky that Sunny Boy and Grandpa Horton liked to walk, for the Parkneys did not live near a car line. There was only one trolley line that went through the River Section, anyway, and they lived many blocks from that. Grandpa Horton carried a large bundle in one hand and a basket Harriet had packed in the other. Sunny Boy had his toys and candy and cakes.

"Here is the house," said Grandpa Horton, stopping suddenly before a house that looked so old and dirty and shabby you would not think people could live in it. The shutters were missing from most of the windows and the door stood wide open.

"Now stay close to me," said Grandpa Horton. "It is dark in the halls, and I don't want to lose you."

It was dark in the halls and dark on the stairs. They passed many doors and they heard people talking, but they saw no one. Sunny Boy followed Grandpa till they had climbed three flights of stairs and were on the fourth floor of the house. Then Grandpa Horton knocked on a door.

"Come in," called a man's voice.

Sunny Boy clung to Grandpa Horton's coat and stared around him. They had stepped into a room that did not look like any room he had ever seen before. There were no chairs at all and only one table. A stove in one corner had a good fire in it, and a man, with one arm in a sling, sat near it, on a soap box.

"How do you do, Mr. Parkney?" said Grandpa Horton cheerfully. "This is my little grandson, Sunny Boy. He wanted to see your children and wish them a Happy New Year."

The man smiled at Sunny Boy and Mrs. Parkney came out of the other room when she heard the voices.

"I believe I'm better," Mr. Parkney declared. "And I've decided to go to the doctor as you said, Mr. Horton. Perhaps if I get this arm well and get a job, I can pay back all you've done for me."

"Why, certainly you can," said Grandpa Horton. "Or you can give some one else a lift, which will be better. Now I want to talk to you and Mrs. Parkney a few minutes. But where are the children? Sunny Boy has something for them."

"They've all gone out, except Bob, of course," replied Mrs. Parkney.

"Well, then, Sunny Boy, suppose you go in and wish Bob a Happy New Year," suggested Grandpa Horton. "Take him his candy and cakes and the baseball game you brought him."

"You come, too," whispered Sunny Boy.

"You're not bashful, are you?" laughed Grandpa Horton. "Well, I'll go with you and introduce you to Bob, then I'll have a talk with you, Mr. Parkney."

Bob Parkney was lying on a mattress propped up between two chairs, not a very comfortable bed for a sick boy. But Sunny Boy did not notice the bed. He stared at Bob and Bob stared at him.

"Well, for goodness' sake!" cried Bob Parkney. "Where did you come from?"

"Why, Sunny Boy!" said Grandpa Horton, much surprised, "do you know Bob?"

"He's the boy—" Sunny Boy began in such a hurry that he choked. "Oh, Grandpa, he's the boy that pulled me off the ice!" he finished in one breath.

"Well, I never!" said Grandpa Horton, in astonishment. "I never thought of that, and Bob didn't mention ice to me. Is that what gave you this fine cold, young man?"

Grandpa Horton tried to frown at Bob, but he only succeeded in smiling. And Bob smiled back.

"I did catch a little cold," the boy admitted. "You see, my feet were sort of wet. But it's most gone now."

"I hope it is. But you're hoarse yet," said Grandpa Horton. "So you're the lad who kept his head and brought my Sunny Boy safely ashore. There are a number of folks at our house, Bob, who would like to tell you what they think of you. We looked everywhere for you the next day and for several days afterward."

"Don't let anybody come!" croaked Bob in his poor, hoarse voice. "Please, don't let 'em come, sir. It was nothing to do. I only kept the lunatics from walking on the little chap. I hate people making a fuss."

"There, there, no one shall make a fuss," Grandpa Horton promised him. "Don't tire your throat with talking. I want to have a word with your mother and father, Bob, so I'll leave Sunny Boy to entertain you. He can do enough talking for two boys when he gets started."

Grandpa Horton went into the other room, and left Sunny Boy and Bob alone. There was no chair for Sunny Boy to sit on, so he stood beside Bob and talked to him. He told him about the "other grandpa" and the funny mistake the short man who wore glasses had made. And he told Bob what the tall policeman had said about good boys not being afraid of the police.

"And he said you were good to pull me off the ice," added Sunny Boy.

"Shucks, that wasn't anything to do," said Bob. "I wasn't afraid of seeing a policeman, either. But they always tell you to get a move on or to go on where you're going, or something like that. I just don't have any use for a policeman."

"You'll get your throat tired," said wise little Sunny Boy, who saw that Bob was excited over the mention of the policeman. He sat up in bed and his cheeks were very red. "I'll show you how to play the baseball game. You don't have to talk to play that."

They were having such a good time playing the baseball game that neither one of them heard Grandpa Horton come into the room. He said it was time for him and Sunny Boy to go home, but Bob was so eager to finish an inning that Grandpa Horton said he would wait a few minutes. Bob won, and this seemed to please him very much.

"I've going to leave word at Doctor Stacy's as we go past his office," said Grandpa Horton, buttoning Sunny Boy into his coat. "He will drop in to-day to see your father and look you over, Bob. We won't try to pay you for what you did for Sunny Boy, but you must understand that you have made at least four good friends for life—Sunny Boy's father and mother and his grandma and grandpa—and we claim the right of friends to look after you. Your father has taken the sensible view, and we've arranged matters so that you will all be more comfortable till your father's arm heals. Then, when he has a job and you're rid of that cold, you must go back to school. Sunny Boy's father may have a place in his office this summer for a boy who goes to school regularly through the winter."

Bob positively grinned with delight as Grandpa Horton and Sunny Boy shook hands with him and said good-bye. He looked so happy that Sunny Boy asked his grandfather, when they were out in the street, if Bob wanted to go to school.

"I don't know about that," replied Grandpa Horton, "though I think he does. But Bob's mother told me he is wild to get in an office. He wants to learn to use the typewriter. The poor lad has been staying out of school trying to earn a little money since his father hurt his arm. That is why he is afraid of policemen, Sunny Boy. He is really playing hookey, though not for his own pleasure. Still, we must see that he stays in school and has a fair chance."

Though Sunny Boy was in a great hurry to get home and tell his mother and his grandma and Harriet about Bob, he was willing to wait while Grandpa Horton stopped at the doctor's office and left word with the nurse there to have the doctor stop at 674 White Street. That was the house in which the Parkney family lived.

What a lot Sunny Boy and Grandpa Horton had to tell when they reached home!

"I never heard anything so lucky in my life," declared Harriet, who always was counted one of the family. "Mrs. Horton, don't you think I ought to make some chicken soup for that boy? If he has a cold he is probably all run down and needs nourishing things to eat."

"I wonder if I would have time to knit him a sweater before we go home Friday," said Grandma Horton. "I could start it anyway, couldn't I, Olive? I would love to knit a pure wool sweater for Bob."

"I must see that he has good clothes to wear to school," said Mrs. Horton.

Grandpa Horton listened and laughed a little. He was sitting before the fire, and he held Sunny Boy on his knee.

"What would you like to do for Bob, laddie?" he asked his grandson. "If you can think of something I'll give you the money to buy it and you and I will go downtown and shop to-morrow."

"I'd like to give him skates on shoes, like the ones Blake Garrison has," said Sunny Boy promptly. "Bob's skates were old, rusty ones, and he had 'em tied on with string, Grandpa. Would skates on shoes cost too much?"

"They certainly would not!" said Grandpa Horton. "To-morrow morning we'll go down to the best store selling sporting goods in Centronia and buy the best pair of skates we can find."

When Mr. Horton came home that night he had to hear all about Bob, of course. And he was as surprised and pleased as the others had been, and at once began to plan to do something for the boy who had been so kind to his own boy.

"He must go back to school as soon as he is well, and from what Dr. Stacey tells me that will be by the time the vacation is over," Daddy Horton said. "I stopped in at the doctor's office on my way home to-night. We'll persuade Bob to go back to school on the promise that he shall come into my office for the summer vacation and be taught shorthand and typing. Doctor Stacey says Mr. Parkney has overworked himself and must go slow for a year. I am trying to find him a job where he won't have heavy work to do."

The next day Mother and Grandma Horton went to call on Mrs. Parkney, and they carried some of Harriet's famous chicken soup with them.

"Harriet always sends some to my friends when they are sick," explained Mother Horton to Mrs. Parkney and, of course, when she said that, no one could feel they were being offered charity.

While Mother and Grandma Horton were visiting Mrs. Parkney, Sunny Boy and Grandpa Horton went downtown to buy the skates for Bob. They spent a long time in the shop, looking at the skates and asking the clerk questions, and finally they bought a beautiful pair of skates "on shoes" of the best leather. The clerk put them in a box and told Sunny Boy he was carrying home the best skates in the store.

"I hope Bob will like them," said Sunny Boy, skipping along beside Grandpa Horton. "Oh, look, here comes the other grandpa!"

The tall old gentleman coming toward them saw Sunny Boy, and smiled. He stopped and held out his hand.

"Well, if it isn't my little ice-pond friend!" he said cordially. "Did you catch cold from those wet feet?"

He shook hands with Grandpa Horton, and Sunny Boy answered that he had not taken cold and asked if he had "found his little girl?"

"Oh, yes, thank you, Adele turned up safe and sound and smiling," replied Adele's grandfather. "By the way, I think friends should at least know each other's names. I am Judge Layton."

"I am Arthur B. Horton," answered Sunny Boy's grandpa. "This is my grandson and namesake, called Sunny Boy for convenience. I'm visiting my son, Harry Horton."

"I've met him a number of times in court," said Judge Layton. "And I am more than glad to know his father and his son. You live on a farm, I believe Mr. Horton? I think I've heard your son mention 'Brookside.'"

The two grandfathers talked about the country and about farms—Judge Layton had been brought up on a farm and had never lost his interest in farming—and Sunny Boy, waiting politely and patiently, was not exactly listening. He was playing with a piece of snow and ice and wishing that Grandpa Horton would hurry so that he could, take the skates to Bob Parkney. Then, suddenly, he heard the Judge say something that sounded very interesting.

"I need an honest man, for while the work is light the place must be well looked after," he said. "I can't get any one I'll trust. Few men with families are willing to go outside the city limits, and there is no one to board a single man. I'd give a good deal to get hold of the right kind of man."

"Grandpa," whispered Sunny Boy, pulling Grandpa Horton's coat sleeve. "Grandpa, Daddy says Mr. Parkney should do light work."

Truth to tell, Sunny Boy had a hazy idea that "light work" meant something to do with electric lights or gas; but though it turned out that Judge Layton wanted a man to take care of a small country place he had bought that winter, Sunny Boy's quick thought proved a happy one.

"I do believe that is the man for you," said Grandpa Horton quickly.

Then, in a few words, he told the Judge about the Parkney family. Of course nothing was settled that morning, but Judge Layton and his wife came over in the evening to see the Hortons and to learn more about the Parkneys. In a day or two the Judge went to see Mr. Parkney, and before the month was out the Parkneys were comfortably established in the farmhouse which Judge Layton insisted on putting in good order for them.

Mr. Parkney's arm was much better and Bob's cold was entirely cured by the time they moved. The four children who were of school age came into Centronia every day on the trolley car and Bob declared that nothing could keep him from going to school now that he had a prospect of learning to use the typewriter that summer. Judge Layton engaged Mr. Parkney to look after the farm during the winter and to see that no tramps came along and set fire to the barns or cut down any of the valuable trees. There was no really hard work for him to do, and he was so contented and happy that he did not seem like the same man. Mrs. Parkney was happy, too. As for the children, they thought Mr. Horton and his family were fairies.

"I never saw such dandy skates," said Bob, when Sunny Boy gave them to him. "They must have cost a heap of money. I can't say thank you right."

"Don't try," replied Grandpa Horton, with a smile. "Just think of them as a gift from a little boy who admires you very much."

Before the Parkney family moved to Judge Layton's farm, Miss May's school had opened, the Christmas holidays were over, and dear Grandpa and Grandma Horton had gone home to Brookside. Grandma had to take the sweater she was knitting for Bob home with her to finish, but she sent it to him as soon as it was done. And a handsome sweater it was, dark gray and warm and comfortable. Bob was delighted with it.

The first day of school, after the holiday vacation, Jessie Smiley, a little girl who sat near Sunny Boy in Miss Davis' room, brought her walking doll to school with her.

"I couldn't leave Cora Florence at home," Jessie explained to Miss Davis. "Santa Claus brought her to me. I thought she could sit in a chair and wait for me, mornings."

Miss Davis shook hands politely with Cora Florence and said that she might stay. The girls were much interested in the doll, and even the boys wanted to make her walk, though of course they privately thought that dolls were rather silly things. But Cora Florence was as large as the youngest Parkney child and wore "real" clothes that one could take off like a real child's. Jessie spent a good many minutes taking off her doll's hat and coat and her leggings and mittens and putting them on again.

"I brought my railroad train," announced Carleton Marsh, the next morning.

He unwrapped a long train of cars and an engine.

"I got 'em for Christmas," he said. "They wind up with a key and you don't have to have any track," and down on his hands and knees went Carleton to start his train.

The assembly bell rang while the train was still running around, and Miss Davis had to catch it and leave it turned upside down with the little wheels whirring around while she marched her class into Miss May's room for the morning exercises.

Several of the children brought new toys with them to school the next day. Perry Phelps carried a sand toy which was a little car that ran up and down an inclined plane when filled with sand. Jimmie Butterworth had a jumping rabbit that took a long hop when you pressed a rubber bulb. Lottie Carr brought her new doll, and Dorothy Peters even carried her toy piano, though it was rather heavy.

"My dear little people!" said Miss Davis, when she saw all these toys, "do you think you will be able to keep your mind on lessons with these delightful and distracting presents arranged around the room? Or shall I put them in the cloak room for you till recess?"